After Kansas became a territory, the political condition of the people of Kansas was freely discussed during the summer of 1855, and several mass meetings were held to consider calling a convention to form a state government. At the time, the political elements of Kansas were varied, each working to serve its own interests, and the leaders of the free-state party saw that something must be done to harmonize them. A movement for armed resistance, which had secretly been gathering force, was revealed at the 4th of July celebration at Lawrence in 1855. The situation was one of peril, not only to the political parties in controversy but also to the territory’s communities. Among many anti-slavery parties, a spirit of dissent grew against an organized movement proposing armed resistance to the territorial government. This sentiment led to the Big Springs Convention.

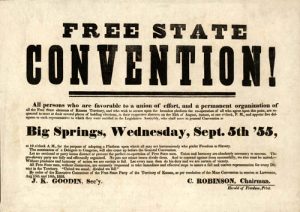

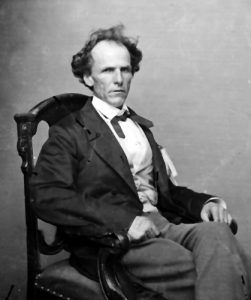

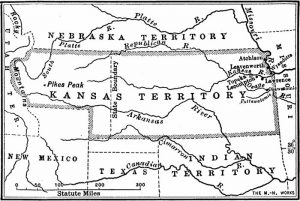

The cause of the complaint was the character of the territorial organization, and the justification of resistance to it was based upon the illegality of the legislature. To avert the revolt of those members of the free-state party who were alienated by the demonstrations of July 4 and the action of the convention held July 11, the leaders of this disaffected branch of the party were asked to assemble for consultation at the office of the Free State in Lawrence on July 17. Among these men were W. Y. Roberts and his brother, Judge Roberts of Big Springs; Judge Wakefield and J. D. Barnes of the California Trail; William Jessee of Bloomington, one of the ousted legislature members; Judge Smith and other prominent free-state men. As the office was too small to accommodate the party, it was proposed to adjourn to the river bank at the foot of New Hampshire Street, where a set of timbers had been erected for a warehouse under the shade of a tree. People they met on the way were asked to the conference, so that by the addition of John and Joseph Speer, editors of the Tribune, S. N. Wood, E. D. Ladd, and G. W. Dietzler were there with 20 men, one of the most prominent being Colonel James H. Lane, who had just returned from the session of the bogus legislature. The spirit of revolt attested in nearly every community against the political action enunciated at Lawrence was considered. After deliberation, the assemblage concluded that the only way to relieve the hazardous situation was by a convention where every community should be fairly represented and free from all local influences. Big Springs was chosen for the location as its situation was ideal. Judge Roberts, one of the proprietors, offered the town’s hospitality, consisting of a rude hotel and several cabins. This village was located about four miles from Lecompton and two miles south of the Kansas River on the Santa Fe Trail in the northwest corner of Douglas County. September 5, 1855, was chosen for the convention’s date, and five delegates were apportioned to each of the 26 representative districts. Calls were printed and distributed in every precinct in the territory.

The movement met with opposition from five of the first councilors — Deitzler, Ladd, S. N. Wood, and the Speer brothers — who feared that such action would divide rather than unite the Free State factions, thus leading to defeat. Under the resolutions passed at Lawrence on July 11, a convention with representatives from nearly every district in the territory assembled at Lawrence on August 14. Its members also opposed the idea of the Big Springs Convention, but when the statement of the situation upon which it was based had been explained, the call was exhibited. The assurance given that while the cooperation of the assemblage was sought, the Big Springs Convention would be held regardless of its assent, the free-state convention issued a call duplicating the first, but dated August 14. This has led to the conclusion by many historians that the only call issued was by this assemblage.

After the conflicting elements had, in a measure, been harmonized, the next step was the election of delegates. The activity of the radical wing of the free-state men somewhat complicated the situation. With the assistance of James Lane, a well-balanced ticket was chosen for the Lawrence District, consisting of 15 of the best men representing the various free-state elements, each of which had a fair representation.

Eight men were from the town, and seven were from the country. The convention, which organized the free-state party, assembled at Big Springs at the appointed time — September 5, 1855. On the evening of the 4th, men from every direction began to gather. They came on horseback, covered wagons, or other conveyances, many with tents and camp outfits. Still, these were unnecessary as the inhabitants pressed upon the delegates the hospitality of their cabins. Roberts had redeemed his promise for a shaded platform with ample seats, and abundant provisions, including free meal tickets, had been made for the delegates’ entertainment. It is estimated that there were over 100 delegates present, representing every district and settlement in the territory.

The convention was called to order at 11 o’clock and temporarily organized by calling W. Y. Roberts to the chair and appointing D. Dodge as secretary. A committee on credentials was appointed with instructions to report immediately. A second committee was appointed to report permanent officers and reported the following list: President, G. W. Smith; vice-presidents, John Fee, J. A. Wakefield, James Salsburg, Dr. A. Hunting; secretaries, R. G. Elliott, D. Dodge, and A. G. Adams. The committee on credentials reported 100 delegates. The usual committees were then appointed, consisting of 13 members representing the several council districts. The most critical committees were those on the platform, state organization, and resolutions, with Lane, Elliott, and Emery as their chairmen. The duties of these committees were as follows: To report upon a platform for the consideration of the convention; to take into consideration the propriety of a state organization; to consider the duty of the people as regards the proceedings of the late legislature; to devise action on the coming congressional election; miscellaneous business.

Colonel James H. Lane, chairman of the committee, presented the report, which was adopted. The substance of it was as follows: To proffer an organization into which men of all political parties might enter without sacrifice of their political creeds; opposition and resistance to all non-resident voters at the polls; that all interests required Kansas to be a free state; that all energies of the party were to be used to exclude the institution of slavery and secure for Kansas the constitution of a free state; that stringent laws be passed, excluding all negroes, bond or free, from the territory, but that such measures would not be regarded as a test of party orthodoxy; that the charge of abolition imputed to the free-state party was without truthful foundation; attempts to encroach upon the constitutional rights of people of any state would be discountenanced; that there would be no interference with their slaves, conceding to the citizens of other states the right to regulate their own institutions; “and to hold and recover their slaves, without any molestation or obstruction from the people of Kansas.”

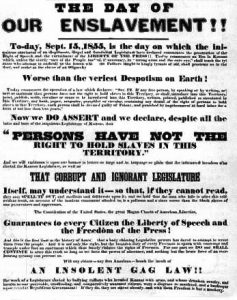

This report called forth much warm discussion as many favored a more radical platform and opposed the clauses alluding to slavery and abolitionists. Still, most members argued that such a conservative platform would be more likely to commend itself to Congress. The inhabitants of Kansas were radical and thus enabled them to accomplish the main objective, excluding slaves from the territory. The committee on the late legislature made a report in which the Missouri–Kansas legislature was repudiated as a “foreign body, representing only the lawless invaders who elected them;” that the “hypocritical mockery of a republican form of government into which this infamous despotism has been converted,” be disavowed and disowned; that the constitutional bill of rights had been violated by the expulsion of members entitled to seats in the legislature, by the refusal to allow the people to select their own officers, by leaving to the people no elections but those prescribed by Congress, and therefore beyond their power to abrogate, and by compelling the people “to take an oath to support a law of the United States, invidiously pointed out, by stifling the freedom of speech and the press, thus usurping the power forbidden to Congress, libeled the Declaration of Independence; and brought disgrace upon our Republican institutions at home and abroad;” that no allegiance was due the spurious legislature and that its laws were invalid, and that resistance to the laws would be made by every peaceful means.

A resolution was offered to impeach the Supreme Court. Colonel Lane objected to this and moved that it be stricken out, but his motion was not sustained. Another resolution recommended the organization and discipline of volunteer companies throughout the territory. The Committee on State Organization reported that its members deemed the movement was “untimely and inexpedient” and caused the first discordant note in the convention. Stirring speeches were made upon the adoption or rejection of the report, but the men in favor of forming a state government argued and pleaded until their point was gained. The report was rejected, and in its place, a resolution offered by Mr. Hutchinson was adopted: “That this convention, given its repudiation of the acts of the so-called Kansas Legislative assembly, responds most heartily to the call made by the people’s convention of the 15th., for a delegate convention of the people of Kansas Territory, to be held at Topeka on September 19, to consider the propriety of the formation of a state constitution, and such other matters as may legitimately come before it.”

The committee’s report on the Congressional delegate changed the time for holding the election from the date set by the legislature to October 9. It was resolved that the rules and regulations prescribed for the March election should govern the election except for the returns, which, by the “people’s proclamation” subsequently issued, were to be made to the “Executive Committee of Kansas Territory” for Governor Wilson Shannon would not, of course, appoint judges of returns for such an election. The election date was changed to the second Tuesday in October (the 9th) to avoid recognizing the right of the late legislature to call an election and avoid the oath to support the slave code.

In the committee’s report on miscellaneous business, ex-Governor Reeder was defended from the charges against him as the cause of his removal. But probably the most important act of the convention was the nomination for a delegate to Congress. The nomination of the free-state delegate was made in a short, forcible speech by Martin F. Conway, who proposed Andrew H. Reeder’s name, and there was no opposing candidate. This action meant Reeder’s vindication and showed the intention to fight the powers that had usurped the territorial government and removed him from office. He was nominated by acclamation.

A committee of three, consisting of S. C. Pomeroy, Colonel James H. Lane, and G. W. Brown, was appointed to wait upon Governor Shannon and present him with a copy of the convention’s proceedings. The Big Springs Convention gave hope and courage to the free-state people throughout the territory. John Speer, who had been opposed to it from the first, said:

“The Big Springs Convention became noted throughout the Union. It was the first consolidated mass of the freemen of Kansas in resistance to the oppressions attempted by the usurping legislature. It was as intelligent, earnest, and heroic a body of men as ever assembled to resist the tyranny of George III. The people came from all portions of the territory. No hamlet or agricultural community was unrepresented. Men started before daylight from dangerous pro-slavery places, like Kickapoo, Delaware, Lecompton, and elsewhere, to avoid assassination.”

As soon as news of the convention’s work had spread, free-state meetings were held at nearly every town and settlement where people could assemble, resolutions endorsing the Big Springs platform were passed, and delegates were chosen for the Topeka Constitutional Convention.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated August 2023.

Also See:

Constitutional Conventions of Kansas

Territorial Kansas & the Struggle for Statehood

About the Article: Most of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text that appears on this page is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing have occurred.