Long before Kansas was established as a territory, it was inhabited by Plains Indians who had no beast of burden other than dogs with a travois and their own backs to move their belongings and supplies.

That changed when Francisco Vazquez de Coronado and the other Spanish explorers introduced the horse, and Indians used them for pack-carrying and riding. Later, the trappers and fur traders developed river transportation, using dugout canoes, bullboats, and flat-bottomed boats. Later, fur companies introduced the heavily timbered keelboats.

The expedition of Lewis and Clark to the northwest in 1804 stimulated the fur trade. The great fur trade companies introduced the keelboat, a large craft of from 20 to 70 tons.

Captain Zebulon M. Pike’s second expedition (1806-07) directed interest to the Southwest, particularly to the Spanish town of Santa Fe, New Mexico, which was rich in trading possibilities. In the next few years, traders from Missouri attempted to participate in this trade, only to be thrown into Spanish jails for their intrusion. But after Mexican independence had been declared in September 1821, Captain William Becknell opened the trade with a pack train taken from Franklin, Missouri, on the Missouri River near Booneville, across Kansas to the Arkansas River near Great Bend, up that stream to the Rocky Mountains, then south to Santa Fe, where he disposed of cotton goods at “$3 per yard” and other items in proportion. The following year, he returned with three wagons, this time crossing the Arkansas River a little west of the present Dodge City, going south over the Cimarron desert, then west to Santa Fe. Thus, Becknell became the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail,” establishing its separate courses and introducing wheeled vehicles, the first to cross the Kansas plains.

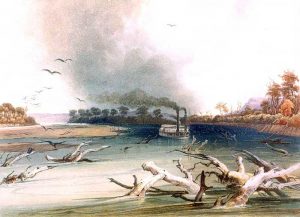

In 1819, the steamboat Western Engineer transported Major Stephen H. Long’s scientific expedition a short distance up the Kansas River and subsequently up the Missouri River. Steamboats, however, were not employed commercially in Kansas until 1829, when a steam packet was placed in operation on the Missouri River from St. Louis, Missouri, to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

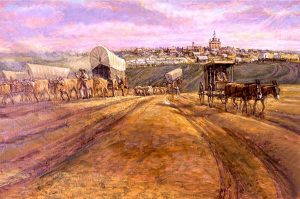

After Mexico gained its independence from Spain in September 1821, it opened trade possibilities with the southwest. That same month, Captain William Becknell left Franklin, Missouri, with four companions and a freight load on his first trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico. His route would become known as the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. More traders immediately followed, and in 1825, Congress authorized the surveying and marking of the trail. Wagons soon outnumbered pack animals, and heavy Conestoga wagons began to be used.

Loaded with cotton and woolen goods, silks, velvets, and hardware from 3,000 to 5,000 pounds and drawn by eight or more oxen or mules, they wended their slow way out of Independence, Missouri, the eastern terminus, in early spring through great herds of northern-bound buffalo. They returned in the fall with horses and mules, blankets, furs, robes, and heavy bags of Spanish gold and silver.

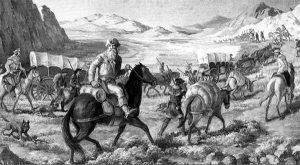

When the Santa Fe Trail was established, a treaty was made with the Osage Indians, who were permitted to cross their lands. But no treaty was made with the Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, and other Plains tribes, who fiercely resented the invasion of their last hunting grounds. In 1828, two white men were killed on the banks of McNees Creek, a tributary of the Canadian River, and retaliation and counter-retaliation followed. Caravans on each trail moved by day in semi-military formation under the leadership of a train captain and rested at night in guarded stockades formed by their interlocking wagons. Each trail was marked with the scars of raids and massacres, by human graves, bones of mules and oxen, household goods and implements, and burned and broken wagons.

The route of the Oregon Trail began to be scouted as early as 1823 by fur traders and explorers.

In 1929, the first steamboats were used commercially in Kansas when a group traveled from St. Louis, Missouri, to Fort Leavenworth on the Missouri River.

In 1830, William Sublette took the first wagons over the Oregon Trail to the Popo Algie River southwest of Lander, Wyoming. Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville crossed the Rocky Mountains via South Pass in 1832 with a train of 20 wagons, paving the way for a few hardy missionaries who settled in the Willamette Valley. Government interest followed, and in 1842, Lieutenant John C. Fremont was sent to locate the South Pass and survey a road into the Territory of Oregon.

In 1837, Colonel Zachary Taylor ordered a commission consisting of Colonel Stephen W. Kearny and Captain Nathan Boone to locate a military road from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Fort Coffey in western Arkansas. When laid out, it was 286 miles long and crossed numerous rivers, including the Spring River, Pomme de Terre, Wildcat, Marmaton, Little Osage, Cottonwood River, Marais des Cygnes, Blue, and Kansas Rivers. Fort Scott was later located on this highway at a point about midway between Forts Leavenworth and Coffey.

On May 22, 1843, a caravan of 875 people, including women and children, in wagons and about 2,000 horses and cattle moved out of Independence, Missouri, on the long journey. From Independence, they followed the Santa Fe Trail to Gardner, Kansas, where later a crude sign gave the simple direction “Road to Oregon.” Here, they turned to the northwest, crossing the Kansas River near Topeka, followed the Big Blue River to the Platte Valley, and proceeded through the South Pass to their destination. That year, the “Great Migration” began along the Oregon Trail.

This trail westward caused increased steamboat traffic on the Missouri River, new supply depots were established, and various starting points were selected. Eventually, numerous roads converged into the main trail. One of the better-known branches was the Cherokee Trail, which started at Fort Smith, Arkansas, and finally struck the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails at Fort Bridger.

The Santa Fe Trail had various starting points along the western border of Missouri and northern Arkansas, with tributary roads branching into it for a considerable distance. By 1843, the annual monetary value of the trade on the Santa Fe Trail was about $450,000.

On May 10, 1849, Captain Howard Stansbury started from Fort Leavenworth. He laid out the military road to Fort Kearny, Nebraska, which, for some distance, followed the California Trail from St. Joseph, Missouri, by way of the Blue River. Shortly after the establishment of Fort Riley, a line of communication was established between Fort Leavenworth and that post, which later was extended to Fort Larned.

Overland freight and mail systems were organized during this time to carry supplies and news to California, Oregon, and Utah. One of the first large freighting companies was Russell, Majors & Waddell, which accumulated a vast amount of equipment. The first contract mail service across Kansas began on July 1, 1850, with two lines originating at Independence, Missouri, and connecting with Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Salt Lake City, Utah. Mule-drawn wagons operated monthly, but the time was no faster than a freighting system.

Travel to the West developed quickly along the various trails. Nearly 90,000 people traveled over the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails between 1849-50. These trails were hazardous and fraught with hardship, including weather, disease, hunger, thirst, and potential Indian attacks.

The demand for news required more speed, and soon, relay stations stocked with supplies and fresh animals were erected along the trails at intervals of 10 to 15 miles, and stagecoaches were introduced. The mail service then increased from monthly to semi-monthly and then weekly. The running time from St. Joseph, Missouri to Denver, Colorado was only six days; Salt Lake City was ten days, and the first through stage from Placerville, California, made the trip in 18 days.

When Kansas was organized as a territory in 1854, the means of transportation west of the Missouri River advanced to the middle of Kansas. Immigrants came by water from St. Louis to Kansas City on the Missouri River, from which point the trip westward had to be made with wagons over a country where few wagon roads had been established. Within no time, steamboat service up the Kansas River began. In April 1854, the Excel, a sturdy sternwheeler of 79 tons, carried 1,100 barrels of flour to the newly established Fort Riley and was soon followed by other boats.

On April 27, 1855, an emigrant company of 75 left Cincinnati, Ohio, on the steamboat Hartford. They traveled down the Ohio River, up the Mississippi River, and west on the Missouri and Kansas Rivers and grounded near the mouth of the Big Blue River on June 1, 1855. The company had brought with them ten houses, ready to put up. Three party members hired a wagon and drove to the present site of Junction City; the rest joined with some other pioneers to establish the town of Manhattan.

Still, the tide flowed on. In 1858, gold was discovered in Colorado, bringing a new surge of covered wagons, then emblazoned with “Pike’s Peak or Bust!” Many of the prospectors did “bust” and returned disheartened, but for each who returned, another always started.

In 1859, the “Parallel Road,” also known as the “Great Central Route,” along the 1st standard parallel to western Kansas and the gold regions of the Rocky Mountains, was laid out. This highway to the Cherry Creek diggings was 469 miles long, 641 miles to Denver, and boasted an abundance of wood and water all the way. That same year, the Kansas Legislature enacted a law providing for the locating and working of highways, collecting a road tax, and providing for 17 new roads. In the next decades, numerous roads were established, and more legislation was created to govern them.

Russell, Majors & Waddell also had a Government contract to transport supplies to the Army in Utah. During 1858-59, it carried more than 16,000,000 pounds of freight, using 3,500 large wagons and approximately 40,000 oxen, 1,000 mules, and 4,000 men. The wagons were made up into “bull-trains,” which proceeded on the trails at regular intervals, from 10 to 12 miles apart, and were manned by crews of “bull-whackers,” who urged the oxen on with picturesque profanity and the pistol-like cracking of long, heavy whips, called bull-whacks.

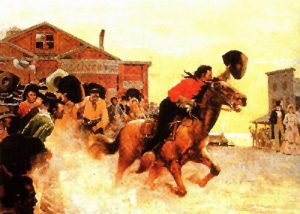

Still, the mail service was too slow, and in 1860, Russell, Majors & Waddell instituted the Pony Express. On April 3, 1860, riders galloped simultaneously out of Sacramento, California, and St. Joseph, Missouri, on stints of 75 to 100 miles each, changing mounts every 1-15 miles to ensure maximum speed. Covering a distance of about 2000 miles, the mail went through in as little as ten days. The Pony Express required 190 stations, nearly 500 horses, and 80 riders. The stations averaged about ten miles apart; a fresh horse was waiting at each station. However, this operation was short-lived as the overland telegraph was completed in October 1861, making it unnecessary.

Along with the major trails through the state, several others would be established for various purposes. The Leavenworth & Pike’s Peak Express and the Smoky Hill Trail extended westward from Fort Leavenworth to Denver, Colorado. The former, stretching nearly 700 miles, was an important stage route utilized by miners rushing to the Colorado gold discoveries. The latter road, which was shorter, served more as a general wagon artery and touched several small but vibrant towns, including Abilene, Salina, and Ellsworth.

During the relatively brief period of the long-distance cattle drive, cowboys used various trails to bring longhorns from Texas to railroad shipping points in Kansas, most notably Abilene, Caldwell, Dodge City, Ellsworth, and Wichita. The impact of these overland arteries gave rise to the most famous cowtowns in American history.

Other lesser-known trails stretched south from Dodge City through Meade before entering the present state of Oklahoma. The Dodge City-Tascosa Trail and Jones and Plummer Trail traveled the same path to Beaver, Oklahoma, then split with one trail heading to Fort Elliott near Mobeetie and the other to the Texas cattle town of Old Tascosa. Later, the Dodge City-Fort Supply Trail and the Fort Elliott-Tascosa military roads served the same region.

The next phase in transportation was the coming of the railroads. While Congress debated building an intercontinental railroad, Kansas impatiently undertook to build its own railroad to connect with the Hannibal & St. Joseph line, advancing to St. Joseph, Missouri. In January 1857, the Elwood & Marysville Railroad was organized, and five miles of track were constructed from Elwood across the river from St. Joseph to Wathena. On April 28, 1860, its first locomotive, the Albany, was ferried across the Missouri River and placed on the tracks. Other railroads were also organized, such as the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, the Chicago, Kansas, and Nebraska, and the Union Pacific Railroad.

The outbreak of the Civil War stopped further independent railway development. However, on July 1, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed an act “to aid in the construction of a Railway and Telegraph line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean.” Three companies — the Central Pacific, Union Pacific, and the Kansas Pacific Railroad — would construct certain portions of the line. By 1865 the road was well underway, but it was a constant struggle with the Native Americans fighting to retain their hunting grounds. Finally, on May 10, 1869, a golden spike was driven at Promontory Point, Utah, and the railroad was complete.

In 1868, the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad began work at Topeka on a route roughly corresponding with the old Santa Fe Trail. By 1872, it had run its tracks to the western border of Kansas and east from Topeka to complete the connection at Atchison. By 1882, Kansas had 3,855 miles of railroad track; in 1905, it had 8,905 miles. In 1917, mileage peaked at 9,367, with only Texas, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Iowa claiming more miles.

The establishment of the railroad ended the era of freight wagons, stagecoaches, and even steamboats. However, it ushered in another form of street railway propulsion — horse and mule-drawn trollies. Many of these were converted to electric railways in the late 1880s. Wichita had one of the first in the Midwest, opening in 1887. Salina had one of the largest, dating from the 1890s, that had 11 miles of track and owned nine cars. It served the commercial district, the town’s cemetery, the college, and the park. Others never converted from animal power, including the Larned Street Railroad, which connected the Santa Fe Depot on the south side of town with the Missouri Pacific station on the north side.

But the automobile introduced a new element. Considered a curiosity at its first appearance in about 1900, it soon became a commercial and domestic necessity. As automobile ownership increased, horses disappeared from streets and public roads, and numerous businesses collapsed, including blacksmiths, horse breeders and traders, harness and saddle makers, and wagon and buggy manufacturers. Eventually, the automobile was also the principal cause of the rapid demise of electric interurbans and street trolleys.

The people then began to demand better roads. Kansas was one of the last states in the nation to create a highway commission in 1917, and it would still be years before any headway was made. In 1937, Kansas had 133,063 miles of roads, with only about 9,000 miles of improved highways. Eventually, after World War II, Kansas caught up and had a dense network of “all-weather” primary and secondary roads.

By the 1930s, Kansas and America were in the throes of the great automobile age. More and better cars appeared, as did expanded gravel and paved road systems, many of which federal dollars made possible. These trends continued. By the post-World War II era, Kansas had tens of thousands of automobiles, trucks, and a dense network of “all-weather” primary and secondary roads.

The state even became a national leader in high-speed, limited-access highways by creating the Kansas Turnpike Authority in 1953 and constructing a four-lane highway that stretched 236 miles between Kansas City and the Oklahoma state line via Topeka and Wichita. Now known as I-35, the turnpike opened in October 1956.

In the meantime, Kansas also took the next step in air transport. By 1939, Kansas had 43 airports, 35 private and municipal fields, six U. S. Department of Commerce fields, and two Army airports.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Kansas Department of Transportation

Kansas Patriot

Kansas State Historical Society

Federal Writers Project; Kansas – A Guide to the Sunflower State, Works Progress Administration, 1939