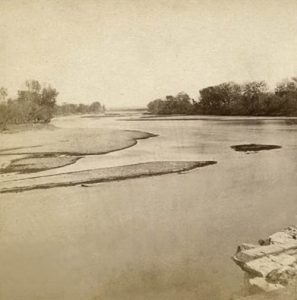

Manhattan, Kansas, located in the northeast part of the state at the junction of the Kansas River and Big Blue River, is the county seat of Riley County.

Before the land was opened to white settlers, the Riley County area was part of the Kanza Indian Reservation. In January 1846, the tribe ceded this land in a treaty signed at the Shawnee Methodist Mission. By the time the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the territory to settlement in 1854, the tribe had been moved.

Immediately, the territory was in turmoil as pro-slavery and Free-State advocates rushed in to make claims.

In the fall of 1854, Colonel George Park of Parkville, Missouri, founded the first settlement in the area along the Kansas River and called it Poleska. The same year, Samuel D. Houston of Illinois and four other men founded the town of Canton at the foot of Bluemont Hill near the mouth of the Big Blue River.

In March 1855, a group of New England Emigrant Aid Company abolitionists traveled to Kansas Territory to found a Free-State town. The company’s goal was to bolster the Free-State cause by expanding the number of antislavery voters in Kansas Territory. Led by Isaac Goodnow, a teacher in Rhode Island, with the help of Samuel C. Pomeroy, they selected the location of the Poleska and Canton for the company’s new settlement. These men soon agreed to join Canton and Poleska to make one settlement named Boston in April 1855. This consolidated group erected several crude houses and purchased more land in the area with funds from the New England Emigrant Company.

The Boston Association adopted a town constitution, approved a townsite survey, erected a warehouse, a temporary river landing, and constructed ferries across the Big Blue and Kansas Rivers. The newly surveyed and platted townsite included a 45-acre park and several market squares.

These people were soon joined by the Cincinnati and Kansas Land Company in June 1855, who were induced to settle at the point by being given half of the townsite of Boston. However, this group wanted to change the town’s name to Manhattan, which was agreed to on June 29, 1855. This newest group had come from Cincinnati, Ohio, on the steamer Hartford and brought ten houses ready to be put up. These houses were commodious for Kansas buildings, some containing eight or nine rooms. William E. Goodnow, who established the first store, used one of the buildings.

That year, the completion of a wagon road from Fort Leavenworth to Fort Riley and another road leading northwest connected with the Oregon Trail and St. Joseph, Missouri, stimulated further land claims.

Though early settlers sometimes found themselves in conflict with Native Americans, and the area was often threatened by pro-slavery Southerners, nearby Fort Riley protected the town. As a result, Manhattan never suffered the deprivations in other Free-State towns during the “Bleeding Kansas” era. This allowed the town to develop relatively quickly.

With its location near the juncture of the two rivers, Manhattan became a strategic river landing during the territorial days when steamboats came up the river and traveled as far west as Junction City. The presence of good quality clay for bricks in the bottomlands and limestone deposits led to the development of large quarries and brickyards and determined the predominant building materials of the town. The wide variety of timber utilized by the first settlers for their homes and business houses included oak, elm, and black walnut.

The first school was taught in 1855 by Mrs. C. E. Blood. George Miller and John Pipher established a store, and when a post office was established on September 4, 1856, it was kept at this store. John Pipher became the first postmaster.

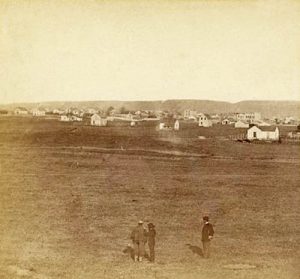

Manhattan was incorporated on May 30, 1857, and the first election of officers made A.J. Mead the first mayor.

In September 1857, the county established four election precincts in preparation for an election to decide the permanent location of the county government. When an election was held on October 5, Ogden received the highest number of votes. However, fraud was later proven, and Manhattan became the county seat. On January 30, 1858, Territorial Governor James W. Denver signed an act officially naming Manhattan as the Riley County seat requiring county officers to move the county records.

The community quickly expanded to include the typical institutional, commercial, and residential buildings that comprise a prosperous riverfront town and county seat. On February 9, 1858, Governor James Denver chartered a Methodist college in Manhattan named Bluemont Central College. The town conveyed many lots to the college to aid their efforts.

The first schoolhouse was built on Poyntz Avenue in 1858 at $2,500. The first church was the Methodist Episcopal, built of stone, in 1858, at $4,800. The Emigrant Aid Company established a combination steam-powered sawmill and gristmill. The military road between Fort Leavenworth and Fort Riley strengthened the local economy. A commercial area evolved in the southeast portion of Manhattan, where the trail crossed the river at the east end of Poyntz Avenue.

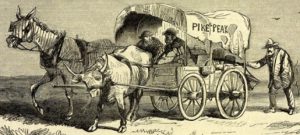

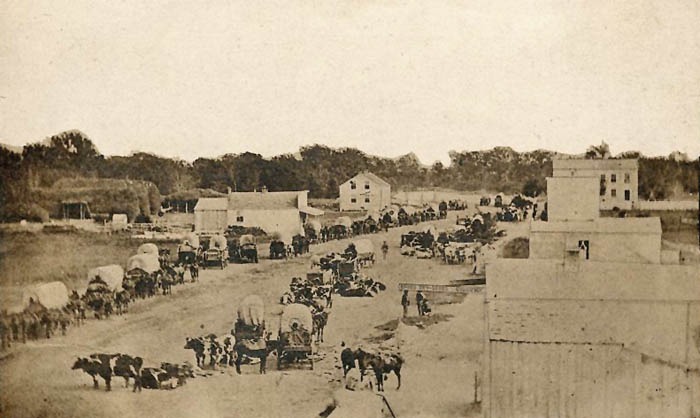

The young city received another boost when gold was discovered in the Rocky Mountains in 1858. By the following year, Fifty-Niners began to stream through Manhattan in their rush to Colorado along the Smoky Hill Trail. One of the last significant settlements on the route west, entrepreneurs built small manufacturing shops, blacksmiths, livery stables, established retail stores, and erected hotels and restaurants. At the river landing, steamboats delivered manufactured goods from the East and loaded cargoes of crops. Within no time, the town’s merchants did a brisk business selling supplies to miners. The road also served as part of the mail route through northern Kansas Territory to the Colorado goldfields.

The same year county officials ordered a stone jail to be built near the southeast corner of the three-acre Public Square. The building also housed courtroom facilities. Various county offices were located in rented space nearby, particularly along Poyntz Avenue. Manhattan’s first newspaper, the Kansas Express, began publishing on May 21, 1859.

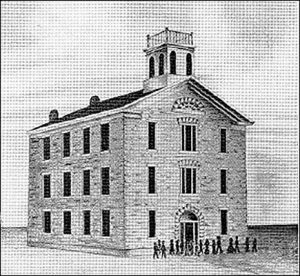

In 1859, college officials laid the first cornerstone for Bluemont Central College, and construction began on a three-story building funded by private donations. The college opened in 1860.

In 1861, when the State of Kansas entered the Union, Isaac Goodnow, who had come with New England Emigrant Aid Company in 1855, began lobbying the legislature to convert Manhattan’s Bluemont Central College into a state university. On February 16, 1863, the Kansas legislature established the Kansas State Agricultural College. When the college began its first session on September 2, 1863, it was the first public college in Kansas and only the second public institution of higher learning to admit women and men equally in the United States.

After the Civil War ended, Kansas became a destination point for settlers from the East and grew rapidly. Manhattan quickly developed an economic base that supported a market and service center.

In December 1865, the City of Manhattan granted the Union Pacific Railroad approximately 20 acres of land for the railroad to erect a depot and other rail-related structures. In 1866, the Kansas Pacific Railroad laid its tracks through Manhattan as it headed westward. This service linked Manhattan to Kansas City and points further east, north, and south. The railroad soon constructed a complex of buildings, including a turntable, engine, pumping and tool houses, and a water tank. A freight depot stood two blocks south of Poyntz Avenue along Wyandotte Avenue. The sawmill was just east of the depot; immediately south of the sawmill were the E. B. Purcell grain elevators and stockyards.

Nearby, at the north side of Poyntz Avenue and 3rd Street, E. B. Purcell started a mercantile business. Two years later, he and his partners purchased the businesses on the southwest corner of Poyntz Avenue and 3rd Street, where they operated five stores under one roof.

By 1870, Manhattan was called home to 1,173 people. Manhattan was one of a few Kansas towns that reserved several centrally located blocks for parks. One of these was the Riley County Fairgrounds, which comprised of 45 acres in the northeast portion of the City. An octagonal stone building called Floral Hall was part of the agricultural display area. It also contained a racetrack. Later it became known as City Park and served as the hub of the City’s social and cultural life.

In 1871, construction crews completed bridges over the Big Blue and Kansas Rivers. The following year, work began on the Manhattan and Northwestern Railroad. In 1872, that railroad and the Manhattan and Blue Valley railroad further expanded rail services. By this time, the city began to see the effects of the dwindling river trade, but the new rail connections compensated for the loss.

In 1871, the town of Manhattan purchased 160 acres of farmland adjacent to the city to incentivize the college to move one mile to the east, closer to town. At that time, the college was still in a rural area two miles northwest of the Union Pacific Railway station, and the road from campus to town was unpaved and impassable for much of the year.

The Manhattan Transfer Company provided horse-drawn coach services between downtown and the campus, a trip that took 30 minutes each way. However, most students roomed in town for the first few years and walked daily to campus. The college built a wood walkway connecting the college and the town to aid the students. It also established an eating hall so students did not have to make the long round trip home for meals.

In 1875, the college campus moved from its original location to buildings on the donated tract, establishing the permanent location of the state college.

The national economy, which included periods of a depressed market combined with grasshopper plagues, restrained economic development during this period. After the economy absorbed the effects of two significant bank failures in 1878, commercial activity improved. That year, 1,526 freight cars of crops and livestock originated in Manhattan.

In 1879, the Manhattan, Alma, and Burlingame branch of the Union Pacific linked Manhattan to Alma in Wabaunsee County and Burlingame in Osage County. That same year, construction began on a branch line of the Manhattan and Northwestern Railroad to connect Manhattan with the mainline of the Kansas Pacific Railway Company, and the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad also became linked to Manhattan.

By the decade’s end, Manhattan was a city of 2,104 residents. By that time, substantial homes, picturesque cottages, dignified churches, brick and limestone business blocks, mills, livestock pens, and lumberyards stood testament to the town’s prosperity.

This sudden population growth reflected the change in the region’s economic climate. By 1880, the population of Kansas fell into two well-defined camps. Emigrants who arrived during the antebellum period lived in the state’s eastern half, while so-called “late comers” from the east occupied the state’s western half.

In 1883, Doctor E. L. Pattee opened a private hospital, the city’s first medical facility, at Poyntz Avenue and 3rd Street.

In 1885, the Union Pacific Railroad located their depot north of the four-story Purcell Mill. Other commercial and industrial businesses relocated near the depot, including the E.

B. Purcell grain elevator, which was one of the largest in the state. A growing number of commercial businesses reflected prosperous times in Manhattan. After the arrival of the railroads, commercial and industrial development shifted to the southeast near the rail lines and moved outward in a northwesterly direction. Two railroad and two wagon road bridges, one of each across the two rivers, provided access to and from the town on the east.

The drought of 1887 ended a decade of optimism as farmers and ranchers could not meet their loans, banks and businesses failed, and thousands of citizens, particularly in the western counties, left the state.

However, Manhattan persevered, and at the end of the decade, the City boasted its first waterworks at Ratone and 3rd Streets and incandescent electric streetlights in its downtown area. By 1890 Manhattan was called home to 3,004 people and would continue to grow every decade afterward.

Though the college campus had been moved to town in 1875, there had been little commercial synergy between town and campus. College faculty and employees erected residences south and east of the relocated campus, just as they had earlier near the original campus in the late 1850s and 1860s. The first business activity was comprised of homeowners renting rooms to students and providing meals. It would be several years before business establishments opened in the late 1890s, including a barbershop and laundry service.

In 1899, after the Kansas Board of Regents closed the college dining hall and bookstore, students had to purchase their textbooks downtown, which was inconvenient due to distance and often mud-soaked roads. College students then established an off-campus cooperative bookstore and a boarding club offering morning and evening meals. Soon afterward, a grocery and meat market appeared nearby. These efforts began what would become the City’s second commercial center. Called Aggieville today, this six-square block area consists of numerous college-age-oriented bars, restaurants, and shops.

In 1900, the city’s population was 3,438, and the college had an enrollment of 1,321.

In 1910 bonds to the extent of $20,000 were voted on to aid in constructing an electric interurban line from Manhattan to Fort Riley. At that time, the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad ran on the north side of the Kansas River and the Union Pacific Railroad on the south, both entering the east. Described as “well improved and well kept,” it had paved streets, an electric street railway, a $50,000 court-house, a $25,000 city hall, three banks, two daily newspapers, three weeklies, and three college papers. Its post office had eight rural routes, and the population was 5,722.

In November 1928, Kansas State Agricultural College was accredited by the Association of American Universities as a school whose graduates were deemed capable of advanced graduate work. Three years later, in 1931, the school’s name was changed to Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science.

In 1950, the city’s population had grown to 19,056.

In 1959, the Kansas legislature changed the college’s name to the Kansas State University of Agriculture and Applied Science to reflect a growing number of graduate programs. However, in modern practice, the “Agriculture and Applied Science” portion is usually omitted even from official documents and state statutes. Several buildings, including residence halls and a student union, were added to the campus in the 1950s.

Today, Manhattan’s economy is heavily based on public entities. The largest employer is Kansas State University, followed by the city school district. Other jobs are provided by nearby Fort Riley, the Kansas Department of Agriculture, hospitals, small manufacturers, and retail.

Kansas State University has an enrollment of nearly 21,000 students. Manhattan is also home to Manhattan Christian College, Manhattan Area Technical College, the American Institute of Baking, the Flint Hills Job Corps Training Center, and the Kansas Building Science Institute.

As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 55,045.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2022.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883

National Register of Historic Places Nomination

Wikipedia