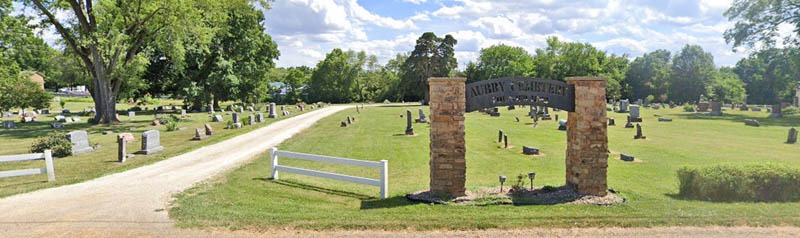

Aubry Cemetery, Johnson County, Kansas, courtesy Google Maps.

Aubry, Kansas, in southeastern Johnson County, was once a bloody battleground during the Civil War’s border troubles.

The County Commissioners organized Aubry Township on May 11, 1858. Before this time, many settlers had taken claims in the area; the first was William H. Brady, who selected his claim on February 22, 1857.

In March 1858, the townsite of Aubry was surveyed, and a Town Company was organized. The company was composed of A. J. Gabbart, President; Greenbury Trekle, Secretary; William H. Brady and Felix Franklin.

Located along the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails, the new settlement was named for Francois Xavier Aubry, a famous Santa Fe trader. A military road that connected Fort Leavenworth to Fort Scott also passed through the area.

The first school district was organized in the summer of 1858, and a 20×24-foot schoolhouse was built. Its first teacher was Sylvester Mann. The building also served as a church and social center until the buildings were built the following year. Reverend Duval preached the first sermon in February 1858 in A.J. Gabbart’s house. The first church organized in May 1859 was of the Christian denomination by Reverend A. Clark. The post office was established on June 21, 1860.

Though the village had a promising start, trying times were coming to Johnson County. When the Civil War erupted in 1861, peace ended abruptly, and many men left to become soldiers.

Troubles had been brewing between Kansas and Missouri for years during the Bleeding Kansas days, when Free-State men fought pro-slavery advocates to decide whether Kansas would become a slave state or a free state. Just months before the war broke out, Kansas had officially entered the Union as a free state, and tensions were still high along the border.

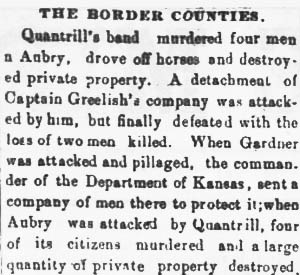

William Quantrill, leader of the guerrilla band Quantrill’s Raiders, often traveled along the Military Road, pillaging and raiding area towns multiple times throughout the war.

On March 7, 1862, Quantrill raided Aubry, killing three men, looting the town, driving off horses, and destroying considerable property. The people of Aubry buried the three men under three cedar trees. This area became the Aubry Cemetery the same year.

As a result, Captain John Greelish led Company E of the 8th Regiment of Kansas Volunteers to Aubry to set up a post on March 10. Two days later, the soldiers won a skirmish near Aubry with about 30 of Quantrill’s men. After this, an additional company of troops was sent to Aubry, and Major E. F. Schneider then took command. The town was then intermittently garrisoned by Union troops for the rest of the Civil War.

Perhaps due to the violence in the area, Aubrey’s post office closed on July 17, 1862.

Later that year, Company D of the 11th Kansas Infantry, under the command of Lieutenant Dick Rooks, manned the post at Aubry. Rooks was a Red Leg and a Jayhawker. This company remained at Aubry through the winter of 1862-63.

Later, in 1863, Captain Joshua A. Pike led 72 men, composed of two companies of cavalry, to Aubry.

Captain Charles F. Coleman, Ninth Kansas Cavalry, was the garrison commander at New Santa Fe, Missouri, in August of 1863. He was notified at 8:00 p.m. by Captain Pike in Aubrey, Kansas, that a large guerrilla force had passed about five miles south of Aubrey and headed into Kansas.

On the afternoon of August 20, 1863, at about 3:00 p.m., William Quantrill passed within sight of the post with about 400 guerrillas and Confederate Army recruits. These men were on their way to raid Lawrence, Kansas. Though Pike formed his men into a battle line south of his post, he took no action to determine the identity of Quantrill’s men or to pursue them once he suspected they were guerrillas. He shared the information about the travelers with all the troops in the area, but he did not promptly notify his superiors.

Captain Charles F. Coleman, in command of the post at Little Santa Fe, Missouri, was not informed until 8:00 p.m. By 9:00 p.m., Captain Coleman marched with 80 cavalrymen to Aubry. Around 11:00 p.m., he joined with Pike’s 100-strong force at Aubry, and the troops set out after Quantrill. Tracking the guerrillas at night was difficult, and Quantrill was so far ahead of them that the pursuers could not possibly catch him.

Making matters worse is that Greenbury Trekle’s father, an 80-year-old man who lived in Missouri six miles east of Aubry, had previously warned authorities at the Aubry post that Quantrill was planning a raid on the city of Lawrence. When he got to Aubry, the officer in charge did not take old man Trekle seriously, and nearly 200 people lost their lives in the Lawrence Massacre on August 21, 1863. Later, when Quantrill’s men heard that Trekle had informed the officer of their plans, they killed him.

“Disaster has again fallen on our State. Lawrence is in ashes. Millions of properties have been destroyed, and worse yet, nearly 200 lives of our best citizens have been sacrificed. No fiends in human shape could have acted with more savage barbarity than Quantrill and his band… I must hold Missouri responsible for this fearful, fiendish raid… Such people cannot be considered loyal and should not be treated as loyal citizens.”

Thomas Carney, Kansas Governor

Pike did not remain at Aubry much longer, but from August 1863 to at least September 1864, one or two companies of the 11th Kansas Cavalry were on duty guarding Aubry.

Quantrill’s Raiders also made other raids in and around Aubry in 1863. On one occasion, five newly arrived citizens were out gathering honey one evening, promising their wives to return early. However, Greenbury Trekle, Mr. Whittaker, Washington Tullis, Mr. Ellis, and John Cody were murdered by Quantrill’s men.

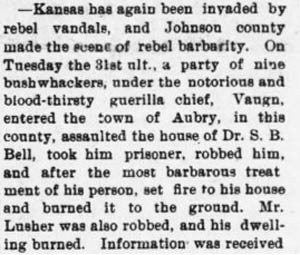

Aubry newspaper clipping, Olathe Mirror, 1864.

Union sympathizer Dr. S. Bell’s house was surrounded by nine bushwhackers under Dan Vaughn, who took him prisoner, assaulted and robbed him, and set his home on fire. Mr. Susher was also robbed, and his house was burned. Numerous fights over the years between Quantrill’s men and the people of Aubry resulted in significant property damage.

On January 31, 1864, Norman Sampson was murdered by Dan Vaughn’s men, who were dressed in Union blue and professed to be Union soldiers.

The garrison at Aubry was removed sometime after September 19, 1864, possibly during the height of Price’s Missouri Raid. This resulted in another raid by about ten guerrillas under Dan Vaughn on January 31, 1865. Word of the impending raid reached authorities in Olathe, and a squad of soldiers rushed into Aubry, arriving too late to prevent the killing of a traveler, the robbery of two residents, and the burning of several houses. Once again, about 20 soldiers were stationed at Aubry, and the post remained active until at least May 1865.

With the war finally over and the area recuperating, Aubry’s post office opened again on June 19, 1866.

At this time, railroads began expanding across Kansas, and the Missouri Pacific Railroad Company planned to build a line from Kansas City to the South. The initial plan was to build through Aubry, Kansas, which would have secured the small town’s future. However, when the area was surveyed, the railroad was concerned about the hills north of Aubry. The Missouri Pacific Railroad company decided to build its tracks half a mile east of Aubry in what would eventually become Stilwell, Kansas.

With the railroad’s arrival in Stillwell, the nearby town was an immediate rival to Aubry. The Aubry general store moved, and many of Aubry’s residents soon moved to Stilwell to get a fresh start. On June 22, 1888, Stilwell, Kansas, established a post office, and two months later, Aubry’s post office closed on August 20, 1888. In the following years, what was left of Aubry merged with Stilwell.

Today, most of Aubry’s old townsite is buried beneath the streets and highways of Overland Park, Kansas. All that is left is the Aubry Cemetery, located between U.S. Highway 69 and Metcalf Avenue, south of W 191 Street.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2026.

Also See:

Kansas Ghost Town Photo Galleries

Sources:

Civil War on the Western Border

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Edwards, Nick; Aubry, Johnson County, Lost Kansas Communities, Chapman Center for Rural Studies, Kansas State University, 2015

Steed, Laura; Ghost Towns of Johnson County, 1973, unknown publisher

Wikipedia