Carry Nation was a temperance reformer, author, and lecturer in Kansas. She was particularly noteworthy for promoting her viewpoints through vandalism.

Caroline Amelia Moore was born in Garrard County, Kentucky, to George and Mary Campbell Moore on November 25, 1846.

Her father was a successful farmer, stock trader, and slaveholder, but he experienced financial setbacks at some point. Her health was poor during much of Carry’s early life, and her education was intermittent. She was a very devout religious child and a student of the bible. The family moved several times in Kentucky and finally settled in Belton, Missouri, in 1854 when she was nine.

In addition to their financial difficulties, mental illness ran in the family. Her mother suffered from delusions at times, and it was said that Mary Moore’s mental state was why the family moved so often. Some historians have speculated that Mary believed she was Queen Victoria because of her finery and social airs. She would live in an insane asylum in Nevada, Missouri, in her later years until her death.

The family moved to Texas in 1862 when Missouri became involved in the Civil War. George did not fare well in Texas, and he soon moved his family back to Missouri. They lived in Cass County when the Union Army ordered them to evacuate their farm. They then moved to Kansas City. Carry nursed wounded soldiers after a battle in Independence, Missouri. When the war was over, the family returned to their farm.

In 1865, Moore met Charles Gloyd, a young physician who had fought for the Union. Gloyd taught school near the Moores’ farm while deciding where to establish his medical practice. Eventually, he settled on Holden, Missouri, and proposed to marry Carry. However, Gloyd was a hard drinker, and Carry’s parents objected to the union because they believed he was addicted to alcohol. However, the couple married on November 21, 1867, and shortly before the birth of their daughter, Charlien, on September 27, 1868, they separated. Charlien was sickly, and Carry blamed her husband for her condition, believing that God punished them because of his drinking. Gloyd died in 1869 of delirium tremens due to his alcoholism.

Influenced by the death of her husband, Carry developed passionate activism against alcohol. With the proceeds from her husband’s estate, she built a small house in Holden. She lived there with her mother-in-law and Charlien. She also attended the Normal Institute in Warrensburg, Missouri, earning her teaching certificate in July 1872. Carry then taught school in Holden for four years. Later, she obtained a history degree and studied the influence of Greek philosophers on American politics.

In 1877, she married David Nation, a lawyer, journalist, and minister who was 19 years old and her senior. They moved to Brazoria County, Texas, to operate a cotton plantation. In 1890, they moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, where David served as a minister. Carry participated in church activities, taught Sunday School, and founded a Woman’s Temperance Union in the town. Her husband was in sympathy with her views on liquor traffic.

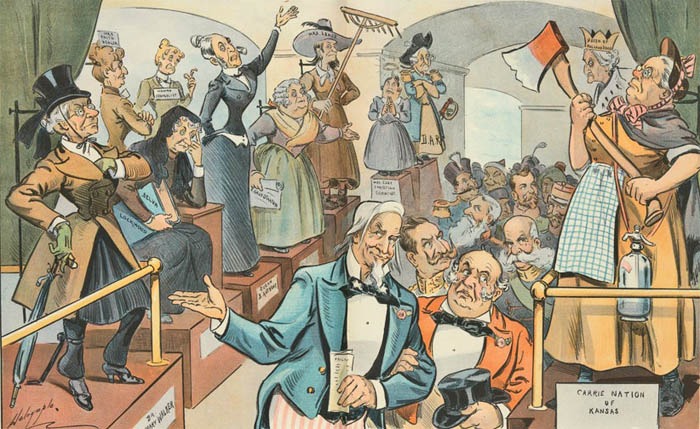

She was an advocate of women’s suffrage and railed against fraternal orders, tobacco, foreign foods, corsets, skirts of improper length, and mildly pornographic art of the sort found in some barrooms.

Carry Nation entered the temperance movement in 1890 when a U.S. Supreme Court decision in favor of the importation and sale of liquor in “original packages” from other states weakened the prohibition laws of Kansas, enacted in 1880. Soon, new saloons reappeared all over the state, flourishing as dishonest police officers and town officials took payoffs.

By 1899 Nation was directing much of her energy towards temperance matters. She initially worked with other local Woman’s Christian Temperance Union members to close seven illegal liquor outlets through non-violent means. However, in the spring of 1900, she turned to more aggressive methods.

In June of 1900, Nation raided several bars in Kiowa, Kansas. The Horseshoe Saloon was the first she attacked, throwing full whiskey bottles, bricks, and pool balls through the window. Carry claimed God told her to go to Kiowa, Kansas, and break up her first saloon. In her view, bars in the state were illegal, meaning anyone could destroy them with impunity. Since it was an “Illegal” bar, no charges were filed against her.

On December 27, 1900, she went into the Carey Hotel at Wichita and demolished the mirrors, glassware, and other items in the room where liquor was sold. Arrested and jailed for several days, she was released on bond. She immediately entered two more saloons, breaking up furniture and emptying liquor bottles.

A formidable woman, nearly 6 feet tall and weighing 175 pounds, she dressed in stark black and white clothing. Sometimes alone or accompanied by hymn-singing women, she would march into a saloon and proceed to sing, pray, hurl biblical-sounding abusive language, and smash the bar fixtures and stock with a hatchet.

On January 26, 1901, 1901, Nation visited Topeka, where she had a spirited interview with Governor William E. Stanley, whom she openly denounced for his failure to enforce the prohibition laws. The Kansas Legislature was in session. Several saloons were illegally operating in the city, including the finest establishment — the Senate Saloon that legislators often patronized.

At that time, the Kansas State Temperance Union was gathering in Topeka for its annual state convention. Carry issued a warning to the saloon keepers of Topeka, but they paid her no attention to it.

On February 4, a brigade of women attempted to rush a tavern but was turned back by a large crowd. The next day Nation and her followers attacked the Senate Saloon, destroying slot machines, a cash register, fixtures, and furnishings.

On February 5, 1901, she wrecked two places where liquor was sold, accompanied by several women. She was arrested and held for a short time but was released and then returned home.

A mass meeting was held at the Topeka auditorium on Sunday, February 10, to demand the enforcement of the laws. On February 18, Nation, with about 100 women, raided all the saloons they could find in the capital city.

They were arrested, tried, and convicted for willful destruction of property. Carry Nation, her hatchet, and radical efforts had come to public notice by this time.

“Oh, I tell you, ladies, you never know what joy it gives you to start out to smash a rum shop.”

— Carry Nation

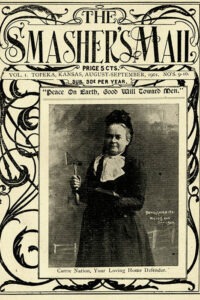

Notwithstanding the decree of the Topeka court, Nation made a tour of Kansas towns, leaving in her wake broken furniture, wasted liquor bottles, and beer barrels. She then began a publication called the Smasher’s Mail, a temperance newspaper in Topeka.

In April 1901, Nation went to Kansas City, Missouri, a city known for its broad opposition to the temperance movement, and smashed liquor in various bars on 12th Street in downtown Kansas City. She was arrested, taken to court, and fined $500, though the judge suspended the fine under the condition that she never return to Kansas City.

She applauded President William McKinley’s assignation the same year because she thought he was a secret drinker and “got what they deserved.” Her husband, David Nation, also divorced her in 1901 on the grounds of desertion.

Carry continued her destructive ways in Kansas, her fame spreading through her growing arrest record. In the first years of the 1900s, she was arrested more than 30 times for “hatchetations,” as she came to call them. She paid her jail fines from lecture-tour fees and sales of stick pins in the shape of hatchets.

She published many newsletters in her fight for prohibition, including the Smasher’s Mail, the Hatchet, and the Home Defender. She also wrote several books, including her autobiography, The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation.

Later, Carry exploited her name by appearing in Vaudeville and music halls in Great Britain. However, audiences in these venues were uninspired by her sermonizing. She called Topeka home until 1905, when she moved to Oklahoma Territory and helped that state enter the nation with a dry constitution.

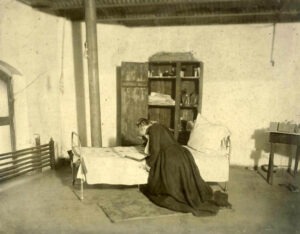

Nation moved to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, near the end of her life, where she called her home “Hatchet Hall”. She got into litigation with a lecture bureau, which caused her a nervous breakdown, and she collapsed during a speech in a Eureka Springs park, after proclaiming, “I have done what I could.” Carry was taken to the Evergreen Place Hospital and Sanitarium in Leavenworth, Kansas.

After lingering for five months, she died there of paresis on June 9, 1911, when she was 65. She was buried beside her mother in Belton Cemetery in Belton, Missouri.

“She was something of a zealot to be sure, a crank, if you will, on the use and sale of liquor and tobacco. But it is an undeniable fact that she opened the eyes of Kansans in 1901 to the truth that their prohibition law was being almost wholly ignored. Her joint-smashing crusade was the beginning of law enforcement in this state which has meant so much to Kansas.”

— Topeka State Journal, the day after her death

Despite her campaign, the enactment in 1919 of national prohibition was largely the result of the efforts of more conventional reformers, who had been reluctant to support her.

Carry Nation’s legacy is enshrined at the Kansas State Historical Society Museum in Topeka. The display includes many items associated with her crusades, including clubs, hatchets, fragments from smashed saloons, her diary, photographs, portraits, and issues of The Smasher’s Mail.

Her home in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, has been restored and contains many original artifacts. Her Hatchet Hall home still stands in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

©Kathy Alexander, Legends of America. Updated February 2025.

Also See:

Prohibition & Alcohol in Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Encyclopedia Britannica

Find a Grave

Kansapedia

Wikipedia