Andrew Horatio Reeder served as the first governor of Kansas Territory from 1854 to 1855. A Democrat who was in full sympathy with the South in supporting the institution of slavery, he advocated for the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which gave residents the choice of whether or not to allow slavery.

Reeder was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, on July 12, 1807, to Absolom and Christina Smith Reeder. He received an academic education at Lawrenceville, New Jersey, before studying law and practicing in his native town. He quickly won distinction as a lawyer in a district noted for its eminent members of the bar. At an early age, he became an active participant in political affairs. Initially, he was associated with the Democratic Party, although not always in harmony with its leaders.

In 1831, Reeder was united in marriage with Amelia Hutter of Easton, Pennsylvania, and the couple would eventually have eight children, but only five would survive.

Reeder was never an office seeker, and when he was appointed Governor of Kansas Territory by President Franklin Pierce in June 1854, he was not an applicant for the position. The United States Senate confirmed his appointment on June 30, 1854; he took the oath of office before Justice Daniel of the United States Supreme Court on July 7 and arrived at Leavenworth, Kansas, on October 7, where he established a temporary executive office.

A week later, in company with two of the Territorial Judges — William Johnston and Rush Elmore — he started on a tour through the territory, which occupied his time until November 7. Upon the slavery question, Governor Reeder sympathized with Stephen A. Douglas, a United States Senator from Illinois, and supported the Kansas-Nebraska Act. When Governor Reeder came into the territory, many assumed that he would allow himself to be manipulated by pro-slavery advocates.

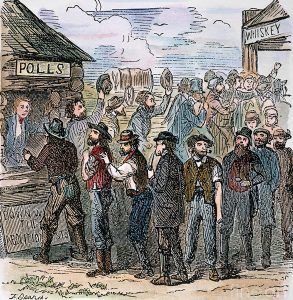

On March 30, 1855, one of the biggest voting frauds in the nation took place when neighboring Missourians came into Kansas Territory to vote illegally on the issue of Kansas being admitted into the U.S. as a free state or a slave state. The incident eventually led to the territory closer to the Kansas-Missouri Border War.

After the March election, the governor was appalled at the extent of the fraud, and his attitude changed. When the Free Soil partisans protested the election results, Reeder agreed to discard the results from the districts where protests had been filed. He called for a new election in the disputed districts in May that was boycotted by the pro-slavery partisans. The governor felt the legislature should convene at a point remote from the influences of the slave state of Missouri.

Meanwhile, a new town association comprised of Free-State advocates was developing the site of Pawnee, Kansas, near the Fort Riley military reservation. Reeder, who owned stock in the town association, 1200 acres of land in the area, and had recently built himself a grand log house there, proclaimed that if the necessary buildings were completed, he would convene the first legislature at Pawnee. The town association quickly went to work, and in May 1855, Reeder issued his proclamation for the legislature to meet there. The pro-slavery supporters, which comprised the vast majority of the legislators, were incensed. They felt that placing the new capitol at Pawnee, some 150 miles from the Missouri border, gave the Free-State advocates in Kansas Territory an advantage. The location was a well-known conflict of interest, but Reeder refused to back down.

The pro-slavery advocates took their complaints to Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War. Davis then ordered a military survey of Fort Riley in hopes that the new town of Pawnee would be found to be within the limits of the military reservation and could be eliminated. However, the new survey reported One Mile Creek as the reserve’s eastern boundary. A map of this survey was prepared and sent to the department, with red lines showing where the boundaries excluded the new settlement of Pawnee. Seeing the town still excluded, the Secretary of War took a pen, drew a red line around it, and wrote on it, “Accepted with the red lines.” He then took it to the president, secured his signature, and issued orders to remove the inhabitants from that part of the reserve.

In the meantime, the territorial legislature was scheduled to convene for the first time on July 2-6, 1855, at Pawnee. During this session, which would become known as the Bogus Legislature, nearly all the members who were opponents of slavery were ousted.

During this meeting, an unwelcome visitor appeared at Fort Riley — Asiatic cholera. At that time, in addition to the garrison, many mechanics and other workmen were employed at the Fort, among whom cholera made terrible ravages, carrying off for several days as many as one-eighth of the population. Before the disease had run its course, as many as 175 would die. The epidemic spread beyond the Fort and reached Pawnee, where eight persons died from its attacks. The first case in Pawnee occurred on July 4, with the legislature in full session. Alarmed by the epidemic and upset about the capitol’s location, the politicians quickly passed a bill for an adjournment of the session to the Shawnee Mission in Johnson County. Governor Reeder vetoed the bill, but the legislature overrode his veto. Before they departed, however, the legislature divided the state’s eastern half into counties, many of which were named for pro-slavery advocates, including Davis County, where Pawnee was situated.

Years later, it and all the other counties so named would be changed. The legislators departed Pawnee on July 6. The territorial government reconvened in Shawnee on July 16, 1855. Pawnee’s status as the capital of Kansas had lasted exactly five days. It is believed to be the shortest-lived capital of any U.S. state or territory.

An order removing Governor Reeder from office was issued in late July 1855, but he did not receive official notice of his removal until August 15. He remained in the territory and took an active part in shaping the destinies of the new state. In October 1855, he was the Free-State candidate for delegate to Congress and won over John W. Whitfield, the pro-slavery candidate. When Congress assembled in December, Reeder went to Washington and began a contest for the seat. The matter was referred to a special committee, which decided that neither Whitfield nor Reeder was entitled to recognition as a delegate, and on August 1, 1856, the seat was declared vacant.

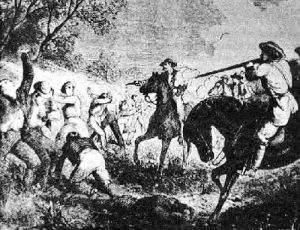

While this committee was hearing witnesses at Tecumseh, Kansas, in the spring of 1856, a pro-slavery Grand Jury summoned Reeder to appear as a witness, the subpoena being served in the presence of the Congressional Committee, he ignored the summons. The Grand Jury then found indictments for treason against Reeder, Dr. Charles Robinson, and others who had aided in the organization of the Free-State government. Again, he disregarded the action of the Grand Jury and defied the officers when they came to place him under arrest.

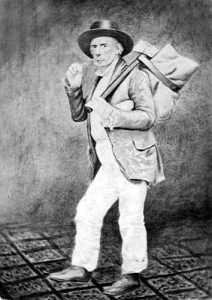

According to a diary kept by Reeder, he remained concealed with a friend near Lawrence until the evening of May 11, 1856, when he started for Kansas City, where he arrived about two o’clock the following day. He remained in hiding at Kansas City until May 23, when he embarked in a skiff with D. E. Adams and was rowed down the river to be taken on board the steamer Converse. Disguised as a woodchopper with a bundle of clothing and an ax, he caught the steamer at Randolph Landing on the 24th and reached the State of Illinois three days later. As he continued his journey eastward, he was given an ovation in each of the principal towns through which he passed, the people assembling in large numbers to welcome him and assure his protection in case an attempt was made to arrest him.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, he was appointed a Brigadier-General by President Abraham Lincoln, but owing to his advanced age, he did not enter the army. Three of his sons, however, took up arms in defense of the Union.

Reeder died at Easton, Pennsylvania, on July 5, 1864, and is buried in the Easton Cemetery.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2023.

Also See: