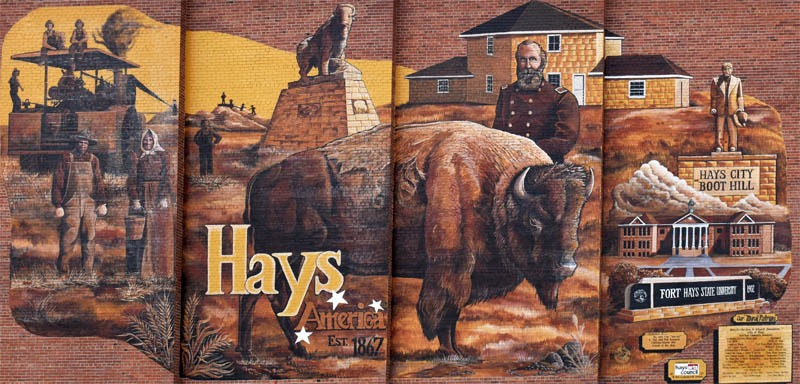

The county seat of Ellis County, Hays, is located a little south of the center of the county at the point where the Union Pacific Railroad crosses Big Creek. When Fort Hays was established in early 1867, and that same year, the Kansas Pacific Railroad planned to make its way to the area, many people thought it profitable to establish a townsite. The first was William F. Cody, who had been hunting buffalo for the Kansas Pacific Railroad, and a partner named William Rose, who established the townsite of Rome in June 1867. The town grew quickly, and the fledgling settlement boasted over 2,000 citizens by the end of July.

Cody and Rose, however, would make a fatal mistake when they refused to take on a man named Dr. William Webb as a partner in their townsite venture. Unknown to them, Webb had the authority to establish town sites for the railroad, and when Cody and Rose refused him, he established the Big Creek Land Company, which platted the town of Hays City on the other side of Big Creek about a mile east of Rome.

A rivalry at once sprang up between the two places, but the railroad company threw its support to Hays City, and Buffalo Bill Cody and William Rose were soon giving free lots away to anyone willing to build or erect a tent in the town. Despite their promotional efforts, many of the citizens and businesses of Rome soon moved to nearby Hays City to be closer to the railroad. A year later, there was nothing left of Rome.

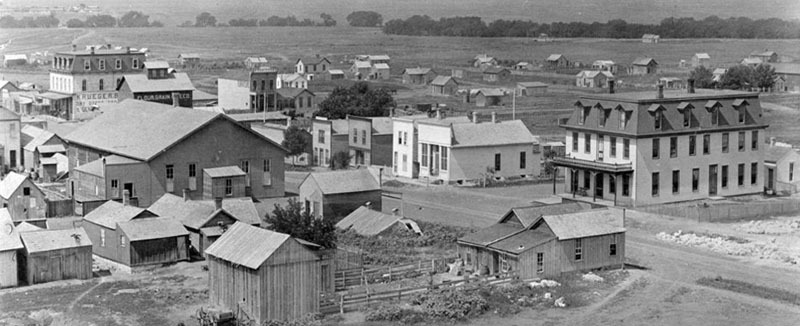

In the meantime, Hays City was prospering as hundreds of people flocked to the new town, especially after the railroad arrived. The town boasted numerous businesses and dozens of new houses within no time. Many previously located in Rome were moved to Hays City, including the Perry Hotel, renamed Gibbs House, and the Moses & Bloomfield general store. In October, another hotel was built by a man named Boggs, and a post office was established. Most of the early buildings were frame structures, but the first substantial improvement was a stone building used as a drug store. The city’s first newspaper, the Railway Advance, was also established that first year. For several years, Hays would be the point from which the west and southwest obtained supplies before the railroad was completed to Dodge City. Within a year, the town boasted more than 1,000 residents.

The city had a brief setback when the railroad pushed westward to Sheridan in 1868, and many businesses moved their buildings to the town. While this temporarily affected Hays’s business, it also had its advantages, as it eliminated many of its desperate characters from the town.

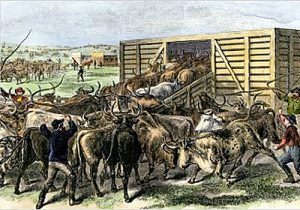

Like Junction City and Great Bend, Hays was never a significant cattle market, but when it was the railroad’s western terminus, it had its days of notoriety. It was one of the most stirring, as well as one of the deadliest places in the West. Business was exceedingly lively as it became the outfitting station for all wagon trains following the Smoky Hill Trail eastward. At the same time, it became the railhead for which thousands of head of cattle were driven northward from Texas to be shipped eastward. Within no time, numerous notorious characters flocked there, giving the place anything but an enviable reputation. Business houses, many of which were only temporary, sprung up like mushrooms, and the dozens opened saloons. At the first meeting of the Board of County Commissioners, no less than 37 licenses to sell liquor were granted in two days. For a time, it seemed like all the disreputable characters of both sexes on the frontier were centered in Hays City. Saloons and brothels flourished, and against the characters that frequented these businesses, the better element of the community was powerless.

Hays City was not an exception to other frontier towns that sprung into existence as the railway stretched westward, but the sheer number of disreputable characters that came there was a curse to the place. The early history of Hays City is one of bloodshed, and the class of desperados placed very little value on human life.

The town was the scene of many an exploit of Wild Bill Hickok from 1867 to 1869, who served as a “Special Marshal.” Hickok’s character for daring and recklessness, his established reputation for knowledge in getting the “drop,” and his sureness of aim made him the dread of others equally bad and reckless as himself. Believing that such a man was the best person to protect the law-abiding people against the thugs, the citizens employed him to help clear the town of lawlessness. While employed, he killed two soldiers and two citizens and wounded several others. After killing the soldiers, he fled to evade military authorities and was next heard of at Abilene.

Hickok, however, was far from the worst character who found his way to Hays City during its early days. Jim Curry was one of the most depraved specimens ever to visit the Western country. He was considered disreputable and wicked without a single redeeming quality.

No person was safe against his attacks — his murderous weapons aimed at all alike. During his short stay in the city, he killed several black men, some of whom he threw into a dry well, and he killed a man named Brady by cutting his throat, after which he threw him into an empty boxcar.

Another time, he was going up the street and meeting a quiet, inoffensive youth named Estes, who was about 18 years old, and told him to throw up his hands. The youth begged that he would not kill him, but the villain, deaf to all such appeals, placed a revolver to the boy’s breast and sent a bullet through his heart, stepped over his dead body, and walked away.

This cowardly act aroused the citizens, who then determined to protect themselves, imposing vigilante-style punishment upon all offenders against life and property. This action drove many evil-doers away, but a great deal had to be accomplished before the town would be tamed.

Not the least of those transactions that darken the pages of this city’s history was an event in 1869. That year, the government had accumulated more military supplies at Fort Hays than could be stored in the room provided, and a large quantity was piled alongside the track, covered with a tarpaulin. Two watchmen looked over them to prevent the goods from being stolen, relieving each other at midnight. The name of one of the watchmen was John Hays. While Hays was on duty one night, he stepped across the street to Tommy Drumm’s saloon to see what time it was. Just as he was about to open the door, three black soldiers came along, one of whom shot Hays dead. These soldiers belonged to the Thirty-eighth Infantry, at that time stationed at Fort Hays, and had come to town that evening and became intoxicated. While in this condition, they undertook to enter a brothel but were refused admission and began to raise a ruckus. They then went to a barber’s shop, where they began to smash things up and caused the black barber to flee for safety.

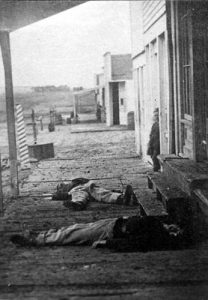

Hays was a violent place in its early days, as evidenced by these two dead soldiers, Privates George H. Sumner and Peter Welsh, in front of a saloon in 1873.

They then resolved to go out and kill the first man they met, and Hays was, unfortunately, the first man they saw — unceremoniously shooting and killing him. The next morning, the barber told the sheriff how the three soldiers had acted in his shop and what he had heard them say. Then, the sheriff took the barber with him to identify the soldiers and went to the fort to arrest the men. The troops were drawn up in line, and the three soldiers were identified and arrested.

The murderers were then locked in a cellar in Hays City to await further examination the following morning. However, that evening, vigilantes took them from the cellar to the trestle-work that crosses a ravine about 400 yards west of the depot, where ropes were adjusted to their necks. They were lifted up and dropped between the ties, where they hung until morning. Railroad men found their lifeless bodies the next day and cut them down. Their remains were then taken back to the fort, where they were buried.

They then resolved to go out and kill the first man they met, and Hays was, unfortunately, the first man they saw — unceremoniously shooting and killing him. The next morning, the barber told the sheriff how the three soldiers had acted in his shop and what he had heard them say. Then, the sheriff took the barber with him to identify the soldiers and went to the fort to arrest the men. The troops were drawn up in line, and the three soldiers were identified and arrested.

The murderers were then locked in a cellar in Hays City to await further examination the following morning. However, that evening, vigilantes took them from the cellar and took them to the trestle-work that crosses a ravine about 400 yards west of the depot, where ropes were adjusted to their necks. They were lifted up and dropped between the ties, where they hung until morning. Railroad men found their lifeless bodies the next day and cut them down. Their remains were then taken back to the fort, where they were buried.

While many of the worst characters left and followed the railroad to Sheridan, Kansas, the majority of the brothels and saloons remained, and in these took place many a bloody encounter. In the spring of 1872, a dispute occurred one evening in front of Kelly’s Saloon on North Main Street. At that time, Peter Lanahan was the County Sheriff, and upon hearing of what was going on, went down to quell the disturbance. Pistols were being freely used, and when the sheriff tried to interfere, a man named Charles Harris, who at that time was working as a bartender for a man named Thomas Dunn, fired at him, hitting the lawman in the abdomen. With the sheriff shot and wounded, a woman named Em Bowen, the proprietress of a noted brothel, ran out with two revolvers, which she gave to Sheriff Lanahan. The lawman then immediately commenced firing, killing Harris instantly. Though mortally wounded, Lanahan then went into the Kelly’s Saloon, where the guns were blazing.

Another man named Kelly, who kept a saloon in another part of the town, was a participant, and when the sheriff commenced firing, this younger Kelly crept under a table, and while there, Lanahan reached over and fired four shots at him. However, the lawman was becoming weak and unsteady from his wound; his aim was uncertain, and Kelly escaped unhurt. Lanahan, becoming exhausted, then sank to the floor and was carried into Em Bowen’s brothel, where several people rendered him the best assistance they could. While there, the younger Kelly, who had escaped from Kelly’s Saloon, returned with a rifle and, placing himself in front of the brothel where Lanahan lay dying, commenced firing into the house, wounding a man named May in the knee. The sheriff was then carried to the courthouse, where he died the following day.

In Hays City, there is a patch of ground known as “Boot Hill,” and why it was thus named will sufficiently indicate what kind of place Hays City was during its early days. This particular piece of ground was the burial place for those who died violently—in gunfights or other aggressive manners. These parties were buried without ceremony, with their boots on, and from the fact that 45 of these rough characters were buried there, it received the name of “Boot Hill.”

Five years after the murder of John Hays and the hangings of the three black soldiers, an outbreak among the black soldiers stationed at Fort Hays occurred in 1874. At that time, the fort was garrisoned by the Ninth Regiment of Colored Cavalry, who sought to revenge the hangings of the three soldiers who had killed John Hays.

One night, a party of the Ninth went to town prepared to “clean it out,” as they expressed it. The people hearing of this were armed and determined to resist the premeditated “cleaning out” process. The black cavalry came into Hays City armed, and a fight immediately began between the soldiers and the citizens. In the end, the citizens were victorious, and six of the soldiers were killed – their bodies afterward were thrown into a dry well. From that time on, the residents of Hays City were determined that law and order should rule.

In the meantime, the law-abiding residents of the town were making progress on establishing a civilized city. The first school was a private one, established in 1869, and the following year, a public school was opened. The following year, Hays became the permanent county seat.

Bonds were issued in 1873 to build a courthouse, and before long, a stone building was erected, the basement of which is used for a county jail. That same year, $12,000 in bonds were issued for the erection of a schoolhouse, which was built about two blocks west of the courthouse. The Hays City Times newspaper was also established in 1873 by Allen & Jones, but its existence was very short.

In February 1874, W. H. Johnson established the Hays City Sentinel, which changed hands several times over the next several years. In 1875, the United States Land Office for the district of Western Kansas opened in a frame building on North Fort Street. That same year, H.P. Wilson built a two-story stone hotel on Chestnut Street known as the Pennsylvania House.

By the mid-1870s, the railroad had extended its tracks farther west, and with it went the teamsters, railroad workers, soldiers, and famous characters of the day. Hays City gradually quieted down and began serving as a point of arrival for immigrants, most notably a group of ethnic Germans from the Volga region of Russia.

First arriving in Hays in February 1876, these immigrants established several small villages around the Hays area, including Antonino, Catherine, Schoenchen Victoria, and several others. That same year, J.H. Downing established the Star newspaper, quickly becoming the city’s “official” newspaper.

In 1877, Henry Krueger erected a large two-story stone building on South Fort Street which was used as a public hall. The first church was built that same year – a frame chapel for the Catholics. Unfortunately, Hays suffered a fire on January 13, 1879, which destroyed the Gibbs House hotel and two grocery stores; a harness shop was also swept out of existence. That same year, however, more substantial buildings were erected, including a two-story stone building on South Main Street that was occupied by Hall & Son Hardware Store, a one-story stone building by H.P. Wilson which held the town’s first bank, a small grain elevator near the railroad, a new Presbyterian Church, as well as several handsome residences. The Lutherans erected their first church the next year, and Henry Krueger built a good-sized grain elevator.

In 1881, Simon Motz built a larger grain elevator, and a large addition was made to the schoolhouse. In December of that year, Hays City was again visited by a fire, which carried away six buildings on South Fort Street. By this time, the boom days of the area were over, and the population had fallen to about 950. However, the town was still called home to six general merchandise stores, three hardware stores, three drug stores, three hotels, a dry goods store, a harness and saddlery shop, a millinery establishment, two book and stationery stores, two jewelry stores, two bakeries and restaurants, two carriage and wagon-shops, two lumber-yards, two newspapers, and a bank. The rest of the population was primarily involved in agricultural pursuits. The German-American Advocate newspaper was established in Hays in October 1882 and published in English and German.

In early 1889, it became known that Fort Hays would be abandoned, and the Kansas legislature adopted a resolution asking Congress to donate the site to the state for a soldier’s home. The fort closed permanently on June 1, 1889, but Congress took no action on the petition for a soldier’s home.

In 1895, Hays City was again struck by fire, this time a devastating one that destroyed some 60 downtown businesses. That same year, the town’s official name was changed to Hays. Also, in 1895, the Kansas Legislature again asked that the Fort Hays reservation be donated to the state as a location for a branch of the state agricultural college, a branch of the state normal school, and a public park.

Again, no action was taken, and in 1899, the Interior Department declared the land open for settlement. However, in March 1900, the Kansas delegation in Congress secured the land and buildings for educational purposes. In 1901, the legislature passed legislation establishing the Fort Hays Experiment Station (part of Kansas State University) and set aside about 4,000 acres for the Western Branch State Normal School.

By the turn of the century, Hays boasted a population of almost 1,300 people. At this time, the city was run by a unique group serving as its City Council, known as the “Boys Council.” They were the youngest council in the United States to govern a city the size of Hays, with the youngest being just 22 years old and the oldest being 30. Despite their age, this efficient group was responsible for reducing the city debt, lowering the tax levy, building and equipping the first engine house, and building a water tank in the event of a fire.

The Western State Normal School began with a summer session in June 1902, and the first regular term opened in September, with an enrollment of 23 students. The school was conducted in the old fort buildings until 1904 when the central portion of the main building was ready for occupancy. By 1910, the total enrollment had increased to almost 1,000 students.

In the first decade of the 20th Century, Hays grew quickly, reaching a population of almost 2,400 residents by 1910. Called one of the most progressive cities of western Kansas, it had an electric lighting plant, waterworks, a fire department, and a telephone exchange, and in the spring of 1911, completed a sewer system. In addition to the Western State Normal School, the city boasted an excellent public school system and St. Joseph’s College, a Catholic institution. Among the industries and financial institutions of the time were two banks, three weekly newspapers (the News, the Free Press, and the Review-Headlight), flour mills, grain elevators, machine shops, marble works, a creamery, good hotels, and several well-stocked mercantile establishments.

Over the next century, Hays continued to grow but was marked by disasters, including devastating floods in 1907 and 1951 and an explosion of three Standard Oil gasoline tanks in 1919, which killed eight people and injured about 150. In 1935, Hays, like the rest of Kansas, was hit with violent dust storms.

But Hays always recovered from hardship and continued to progress. In 1914, the Western State Normal School separated from the school in Emporia and became Fort Hays Kansas State Normal School. It became the Kansas State Teachers College of Hays in 1923, and its name was changed to Fort Hays State College in 1931. It was elevated to university status in 1977.

In 1917, its dirt streets were bricked, and by 1920, the population had reached more than 3,900 people. In 1931, the Palmer Stormkind oil field was founded, bringing more people to the area, and in 1943, the nearby Walker Army Air Field was built, adding 1500-2000 people to the population.

By 1950, Hays had grown to a population of 9,378; in 1955, Old Fort Hays opened as a museum. The Kansas Historical Society later acquired it and became a Kansas State Historic Site in 1967. The site features four original buildings: the blockhouse (completed as the post headquarters in 1868), a guardhouse, and two officers’ quarters.

Today, as a center for education, business, and culture for western Kansas, Hays is called home to about 21,000 people and continues to display its rich history at not only Historic Fort Hays but also at the Ellis County Historical Museum, Sternberg Museum of Natural History, and the Boot Hill Cemetery. A historic walking tour of downtown provides 25 bronze plaques explaining the significance of sites where the famous and infamous walked the streets of Old Hays City. A brochure is available at the Hays Convention and Visitors Bureau located at 2700 Vine St. Frontier Park, located directly across from Historic Fort Hays, which includes 89 acres of land that features several walking trails, waterfalls, and scenic views, as well as a buffalo herd.

Contact Information:

Hay Convention & Visitors Bureau

2700 Vine Street

Hays, Kansas 67601

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2024.

Also See:

Places and Destinations in Kansas

See Sources