On February 1, 1888, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union of Beloit, Kansas, opened a reform school for girls. This school was kept up by private contributions until the meeting of the legislature in 1889 when a law was passed appropriating $25,000 for the establishment of a reform school for girls at Beloit, provided that the city would secure a suitable tract of land, without cost to the state, not less than 40 acres, within three miles of the city, the site to be approved by the state board of charitable institutions. The people of Beloit donated a tract of 80 acres within half a mile of the city, and on March 18, 1889, the state took over the school that had been started the year previous by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. A building capable of accommodating 100 inmates was erected, and the first commitment was from Butler County on May 10, 1889.

The act creating the school gave courts of record and probate courts the power to commit:

1. Any girl under the age of 16 years who might be liable to punishment by imprisonment under any existing law of the state.

2. Any girl under 16, with the consent of her parent or guardian, against whom any charge of violation of law might have been made, the penalty would be imprisonment.

3. Any girl under 16 who is incorrigible and habitually disregards the commands of her father, mother, or guardian, who leads a vagrant life, resorts to immoral places or practices, and neglects or refuses to perform labor suitable to her years, and to attend school.

Every girl so committed to the institution was required to remain until she reached the age of 21 unless sooner discharged upon the superintendent’s recommendation. However, girls might be apprenticed or dismissed upon probation, to be returned to the school if they proved untrustworthy.

The aims and objectives of the industrial schools were to surround wayward boys and girls with an atmosphere of refinement and morality, which aided in their reformation, and to teach them the rudiments of some useful employment that would place in their hands the means of supporting themselves after being discharged from the institution. The boys were taught tailoring, shoe and harness making, woodworking of various kinds, baking, printing, etc. A printing press was installed in the boys’ school, and a monthly paper called the Boys’ Chronicle was issued and circulated throughout the state and mailed to similar schools elsewhere.

The girls were taught sewing, weaving, cooking, gardening and horticulture, wood carving, clay modeling, and the general duties of the household. They were also involved in the daily operations of the farm, garden, and kitchen and hosted and organized holiday events, such as the Independence Day Parade in 1938.

Music was taught in both schools, which were provided with libraries.

The school implemented a cottage system of housing in 1908. This allowed the girls to have a greater amount of freedom while staying under the careful watch of the officer in charge.

The school’s first parole officer, Emma Sells Marshall, gave her first report in the school’s 1914 Biennial Report.

In her 1922 Biennial report, Superintendent Lyda J. McMahon alluded that the school’s academic department was lacking upon her arrival. Temporary school rooms were set up in the school’s Administration Building, and Lula Coyner was appointed principal.

By 1924, the school’s academic work was divided into a morning and an afternoon session. Girls from the third through the ninth grade were taught subjects such as reading, arithmetic, history, English, physiology, and home nursing. The average class size was 15 to 20 students.

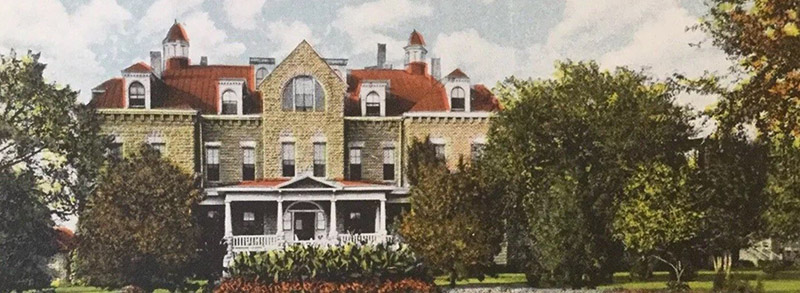

Girls Reform School in Beloit, Kansas, courtesy of Kansas Historical Society.

The school received significant negative press in Kansas, especially in the 1930s, when reports of sterilizations of a large portion of its inmates emerged, for which the process of the law appeared to have been circumvented. The reason for such action was simple: female delinquency, for which the inmates were punished.

The first forced sterilization law was passed in Kansas in 1913. It was later repealed and replaced on February 27, 1917, by Chapter 205 of the Kansas statutes. The Revised Statutes of Kansas for 1923 mentioned the girls’ school, which gave the school and seven other institutions legal power to sterilize inmates. Under these laws and statutes, 71 inmates of the Girls’ Industrial School were recommended for sterilization, and 62 inmates of the Girls’ Industrial School received sterilization operations by 1936.

The sterilizations were carried out at Lansing Correctional Facility in Lansing, Kansas, then called the Women’s Industrial Farm. Lula Coyner, the superintendent of the school from 1926 to 1936, cited venereal diseases and other physical and mental illnesses as the deciding factor in these sterilizations. Coyner was replaced by Superintendent Blanche Peterson shortly after the sterilizations were reported.

Kansas congresswoman Kathryn O’Loughlin McCarthy condemned the sterilizations in 1937 in a newspaper article. The article started a national conversation about the ethics of forced sterilization on young women. McCarthy called for the State of Kansas to begin an investigation into the sterilizations, alleging that parents had not given consent for their daughters to be operated on and that the reasons behind the sterilizations didn’t fall in line with state standards. The sterilizations at the girls’ school were condemned by the Franklin D. Roosevelt Club in Kansas City, Kansas, in November 1937.

Recommendations for sterilization were made by Dr. George A. Kelly and his associates from Fort Hays State University, who held psychology clinics for the inmates of the girls’ school at the request of the administration. Dr. Kelly continued to work with the girls’ school through the 1938 fiscal period. Superintendent Blanche Peterson did not mention the sterilizations or the subsequent media coverage in her 1938 report. The sterilization of inmates of Kansas prisons remained legal until 1965.

In December 1945, the school’s Administration Building, which had housed employee apartments, girls’ dormitories, offices, and the chapel, was lost to a fire. The building was original to the state’s acquisition of the school, having been donated by the city of Beloit in 1890. Though the state initially allotted $135,000 to reconstruct the building in 1945, the ground could not be broken. Construction on the new building started during the 1948-1950 two-year budget period. The new Administration-Dormitory Building was completed in 1952.

By 1966, the school was no longer considered a place of punishment for incarcerated girls. It became an institution more focused on the girls’ healthy mental and emotional development and gave them the foundation needed to enter society. The four treatment areas were academic, vocational, group treatment methods for mental health issues and psychotherapy.

According to the Handbook for Students and Parents published by the school in 1972, the girls would first arrive at the school with their parents. Both parents and girls were introduced to staff and given a facility tour. The girl would then be separated from her parents, given an interview, and settled into one of the three first-level admissions cottages, where they would stay for nine to twelve months. After that initial period, in which girls would receive various medical, psychological, and educational tests, they would be moved to the Grandview second-level cottage, where they would begin evaluations to be released home. This cottage came with an extra level of freedom. The third-level cottage, Prairie Vista Cottage, provided more treatment for girls who had difficulty adjusting. Parents could not visit their daughters at the school until the social worker had approved visitation rights. Boyfriends were not allowed to visit.

The school’s name was changed to the Youth Center at Beloit on July 1, 1974.

To combat the cycle of abuse, the Youth Center implemented parenting classes in the Spring of 1980. The normal educational staff originally started the program with the intent that a full-time instructor would take it over.

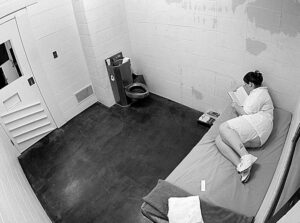

The first comprehensive annual report of the Youth Center at Beloit was filed in 1985. This report detailed the treatments used by the school, including room confinement, security, and seclusion control. These measures were put in place to allow students to calm down or to protect students from themselves and others. The report stated that these confinements were monitored by staff. The longest use of the security status for a student in 1985 was 248 hours.

The 100th Anniversary Celebration for the Center was held on February 9, 1990. It included a ribbon cutting, a presentation of the center’s history, and a speech by the then-current president of the Kansas Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Former school residents returned to the center to catalog how their time spent at the Youth Center had been valuable in their lives. The Youth Center also hosted the annual Women’s Christian Temperance Union’s state convention in September of that year.

Approximately 30 documented assaults on staff were carried out by residents of the center in 1990. Because of this increase in physical violence, the center introduced Aggression Replacement Training led by Greg Peak, the center’s Psychologist.

The center’s name officially changed again to the Beloit Juvenile Correctional Facility on July 1, 1997. The facility also switched state governing agencies from the Child Welfare System to the Kansas Juvenile Justice Authority.

The state closed the Beloit Juvenile Correctional Facility in 2009 due to its decreasing need and high costs. Those still housed at the school’s closing were moved to the Kansas Juvenile Correctional Complex in Topeka, Kansas.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, December 2023.

Also See:

One-Room, Country, & Historic Schools of Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

NBC News

University of Vermont

Wikipedia