Chief Black Bob and his Shawnee band of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, lived on land controlled by Spain in eastern Missouri that was granted to them in about 1793 by Baron Carondelet. In 1808, Chief Black Bob and his Hathawekela division of the Shawnee tribe refused to remove with the rest of the Shawnee tribe to Indian Territory (Oklahoma.)

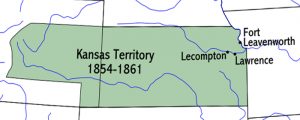

When Missouri became a state in 1821, white settlers rapidly spread westward onto the territory of Native Americans. In 1825, the federal government negotiated the Treaty of St. Louis, which removed 1,400 Missouri-based Shawnee to lands in Kansas. The Shawnee reservation in Kansas stretched from the Missouri State boundary nearly to modern-day Junction City, Kansas, and from the Kansas River to about the southern line of Johnson County.

The Cape Girardeau band believed government commissioners had misled them about the 1825 treaty. They argued that they had never agreed to allow any Ohio Shawnee to settle on the western lands. As a result, a portion of the Shawnee under the leadership of Black Bob did not move to eastern Kansas and instead settled along the White River in Arkansas. In the meantime, the Rogerstown and Fish bands traveled to eastern Kansas, where successive parties of Ohio Shawnee joined them over the next several years.

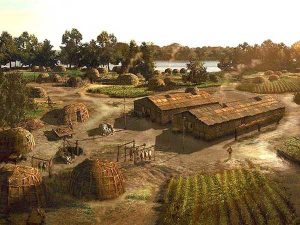

The Shawnee had dwindled over the years due to American encroachment and Indian Removal policies. They had a history of partial assimilation into European American culture and traded heavily with Americans. Portions of the Shawnee nation agreed with the tactic of assimilation and even with removal, hoping that the U.S. government might finally leave them alone. Other Shawnee disagreed and wanted to retain traditional culture and remain on their ancestral lands. The Kansas reservation brought nearly 2,000 members of these divergent factions of the Shawnee nation together.

With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, the U.S. government’s new goal was to open Kansas for settlers from the United States. The government mandated the placement of the Native Americans who remained in the new Kansas Territory on individual land allotments rather than on large reservations. The government exchanged 1.6 million acres of Shawnee reservation land in Kansas for individual grants of 200 acres for each Shawnee man, woman, and child. Shawnee land holdings were reduced to roughly 200,000 acres, within 30 miles of the Missouri border. The government permitted the Shawnee to stay on their lands in Kansas only if they accepted individual allotments. Those who did — perhaps 700 or more — were called the “severalty” Shawnee because of their individual land ownership.

However, the “Black Bob Band” of the Shawnee, under the leadership of a Chief Black Bob, vehemently refused to accept individual allotments in 1854. The Black Bob, less than 200 in total, were traditionalists who rejected assimilation, protested the federal government’s policy of Indian Removal, believed in communal land ownership, and were vocal critics of the Shawnee National Council. The council consisted of leaders who agreed with assimilation and who allied themselves with the federal government rather than traditional leaders and hereditary chiefs.

For Black Bob and his followers, accepting the government’s offer of individual land grants signified the forfeiture of their rights as tribal members. The government set aside a tract of land for the Black Bob Band, totaling 33,000 acres in southern Johnson County. Black Bob’s band then moved to Kansas. While the U.S. government recognized the acreage as individual allotments accumulated in one place, the Black Bob Shawnee viewed it as a single allotment for communal living. In 1857, there were 136 Black Bob Indians. They continued to live as had been their custom, visiting other tribes and hunting until the Civil War broke out in 1861.

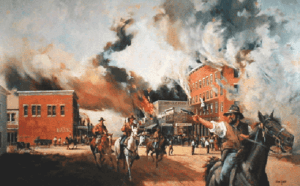

During the Border War with Missouri and the Civil War, Black Bob’s land was directly in the path of warring vigilante groups. As a result, the Indians suffer robbery and losses at the hands of pro-slavery bushwhackers and Kansas thieves. Pro-slavery vigilantes under William Quantrill raided the Black Bob reservation in September 1862. Exposed on both sides and uneasy, they finally left Johnson County and traveled to the Indian Territory for protection.

When Black Bob and about 100 band members returned in 1866, they found white squatters had taken possession of some of the land. To make matters worse, James B. Abbott, an ex-Indian Agent to the Shawnee, and H.L. Taylor, his successor, contrived a scheme to swindle land from the Black Bob band by illegally selling land to squatters. In 1866, they applied for partitioning the Black Bob’s common property and requested individual allotments for 69 band members. The Black Bob band, which did not initially know about the application in their name, drew attention to the fraud, asserting that no one could speak for their Band. Their anger was pointed at untrustworthy federal officials and the National Council of the Shawnee.

Chief Black Bob kept his band together until he died during this time, either in 1862 or 1864. Afterward, his followers maintained their independence from the rest of the Shawnee nation and the national council. In 1867 the speculators induced the Indians to get their land in severalty, and the land was sold to different parties for various prices. The first sale was made on October 28, 1867.

The legal issue of land title became so complicated and expensive to fight that, in the end, it was too much for the Black Bob band to overcome. In the 1870s, after many years of struggling to have their Kansas land titles recognized, the Black Bob Band was finally subjected to government removal. In 1879, President Rutherford Hayes officially removed Black Bob and his tribe to Oklahoma, ending all Native American settlement in Johnson County. Although they did not accept U.S. citizenship, they joined other Shawnee bands in Indian Territory on a joint Shawnee-Cherokee reservation.

The Black Bob Reservation was located on 33,000 acres in the southeastern part of Johnson County, Kansas, at the sources of Blue and Tomahawk Creeks, lying in Oxford, Spring Hill, Aubry, and Olathe townships. Today, the Tomahawk Creek area is near the current intersection of 119th and Black Bob Road east of Olathe, Kansas. Today, this is the Stanley neighborhood of Overland Park, Kansas.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Johnson County History

Wikipedia