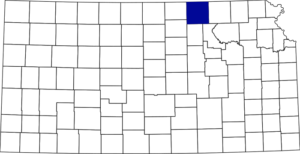

So far as is known, Indians never killed anyone within the limits of Washington County, Kansas. Still, the county’s people, especially during the raids of 1863 and 1864, were often panic-stricken and deserted the county en masse twice.

Until the breaking out of the Civil War and the removal of military forts of troops, the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other wild tribes were kept in check. They did not claim that their rights were molested as long as settlers kept east of a line drawn from the Great Bend of the Arkansas River to the Republican River. However, as soon as they realized that most of the troops were engaged in other business than keeping them quiet, they began to make demonstrations, quarreling with the Otoe and falling upon the whites.

In the spring of 1864, bands of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho appeared along the Little Blue River in Washington and Marshall Counties on the warpath — following the Otoe toward their village. They were armed with bows and arrows, spears, and raw-hide shields. They first plundered John Ferguson’s house on Mill Creek, then O.S. Canfield’s. They found Mrs. Canfield in the house alone, and a dozen of them outraged her horribly. Rufus Darby was returning from Marysville, riding a pony, upon which he had thrown a bag of provisions. He was entirely unarmed, and his feelings may be imagined when he observed 15 to 20 of the wild men of the plains dashing toward him, brandishing their long spears and otherwise conducting themselves like blood-thirsty fiends. They surrounded him, grunting savagely, “Pawnees?” asked their prisoner, in fear and trembling but hoping for the best, “Cheyenne,” answered they in chorus, glaring at him savagely.

He thought that now his time had surely come, especially as they told him, with a scowl, when he remarked that he was going to his wigwam, “No go wigwam; this way.” All except two of the Indians then galloped away in the direction indicated–toward Mr. Hallowell’s. His provision bag, which had tumbled from his pony, was replaced, and with an Indian guarding him on each side, Mr. Darby was silently guided toward the Hallowell house. When he arrived, he found young Mort Hollowell, a stout young fellow of 18, engaged in a hand-to-hand conflict with a Cheyenne brave for possessing his new Sunday overcoat. The Indians had not, so far, offered to take away anything without leaving a buffalo robe in exchange. Young Hallowell wanted to keep his coat, and the Cheyenne buck wanted it too.

When Mr. Darby arrived, the Hollowells were so surprised that hostilities ceased, and the Cheyenne warrior darted off into the bushes with his precious loot. Mr. Darby entered the house and, seeing a gun standing against the wall, picked it up and fingered it carelessly, not knowing whether it was loaded or not. The Cheyenne, however, took the alarm and scattered. The Hallowells and Mr. Darby went in pursuit, armed with three guns, and Mortimer recovered his best coat. Although the Darbys and the Hallowells escaped luckily, others were not so fortunate. A general panic ensued, and most of the settlers in the county fled south and gathered at the house of Orville Huntress near the present site of Clay Center. About 200 people encamped there until the scare was over.

Following is Dr. Williamson’s account:

“The first place they struck was Mr. Furguson’s, afterward Mr. Canfield’s, one of the oldest settlers on the Creek, plundering the houses and insulting the women. Traveling down Mill Creek, near Mr. Wertman’s, the Indians took prisoner Rufus Darby. With one on each side of him, armed with spears, they took him down to Washington to the log house of Jesse R. Hallowell, where another band of Indians were plundering his house of bedding (they called it swapping). Leaving there, they followed down Mill Creek, plundering on their way and taking bedding and blankets from G.M. Driskell. Rich Bond they corralled on the mound above John Bond’s barn. Andy Oswalt was also taken prisoner. After taking them a few miles down the creek, they let them go. Many citizens took the alarm and started for Marysville, in Marshall County. The citizens that were left then held a meeting in Washington at the Collins’ stable; the result was that William Cummings and D.E. Ballard were appointed to reconnoiter the whereabouts of the Indians and ascertain their number. Saddling their ponies, armed and equipped with rifles, revolvers, and blankets, they started south. Night found them at Parson Creek, hungry, tired, and cold, but no Indians. By this time, the boys found that they had no matches. I suppose they rubbed two sticks together, but it wouldn’t work, so they hung up a blanket, shot into it, made it smoke, then raised the wind, took puff about till they got a fire, and got some supper. The following day, bright and early, our scouts started south again, but still no Indians. But resting at noon, they found what proved to be bituminous coal. Filling a blanket with the same, they returned home, showing their treasure, now known as the Clyde coal banks.

“Still later in the fall of the same year, there were Indian troubles, and J. R. Hallowell, Mort Hallowell, and the women and settlers around forted up in the Humes’ log house in Washington, keeping guard overnight. Just at sunrise, a dark object was seen crawling up the ravine by the parsonage. Some of them wanted to shoot, but about that time, Elijah Woolbert, Sr., rose, waved his broad brim hat, and shouted at the top of his voice, “Halloa, you wouldn’t shoot a native, would you?” The following fall, scouts brought word from the west that the Indians were attacking the settlements. The citizens of Mill Creek, with their cattle, oxen, and wagons, pushed to Washington, camping on the highland on what is known as the George Shriner farm south of Washington. That night, the lowing of cattle, the lamentation of the women and children, and the bleating of the sheep might be heard, for they were leaving with their chickens and all their household goods. Some pushed to Harden’s Ford the next day, returning home in a few weeks as the excitement subsided.”

Republican River in Kathy Alexander.

In August 1864, the Cheyenne and Arapaho came up the Little Blue Valley again, waging war against the settlers of Colorado and Western Kansas. Near Oak Grove, six miles above Hanover, a family named Eubanks were scalped and murdered, several men killed in that vicinity, and a young lady named Laura Roper was carried into captivity. Most of the settlers in this county fled to Marysville, where a public meeting was called to discuss ways and means of self-protection. Rufus Darby was chairman of that meeting, and G.H. Hollenberg was treasurer. Money was raised to pay scouts $4 or $5 per day to scour the country and report any traces of the enemy. This was done for several days, the excitement died away, and the settlers of Washington County and other alarmed districts returned to their homes.

The Indians were afterward pursued by the State Militia and driven toward the source of the Republican River. A company was raised in this county, and Mr. Hollenberg was active in the muster and commanding a regiment. From all reliable accounts, the State troops had the plundering propensity quite strongly developed. The advantage gained by the settlers who owned property was that they were not in danger of their lives from the soldier boys, but they kept a sharp eye upon the hens and pigs and all eatables of a fascinating nature to healthy appetites. Neither could the boys resist a buffalo hunt, and several delays were occasioned in their pursuit of Indians by the unsoldierly pursuit of the shaggy animals.

In 1868, the Indians made another raid through Washington, Cloud, and Republican Counties. Their depredations here were confined to thieving, unlike the raid of 1864, which was noticeably destructive of life in this vicinity.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, December 2024. Source: Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Also See: