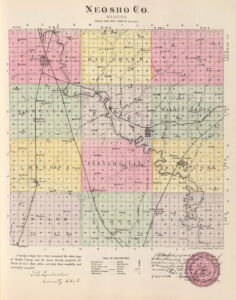

Jacksonville, Kansas, is an extinct town in Lincoln Township of Neosho County. It was located on the corners of Crawford, Neosho, and Labette Counties and about 100 yards from the corner of Cherokee County. The town center was about half a mile from Hickory Creek, a tributary of the Neosho River.

The town started in 1866 when Marion L. McCaslin, with a covered wagon for his grocery store, arrived in the Neosho Valley and began doing business there.

A post office was established on July 8, 1867, with Marion L. McCaslin as postmaster. Once the second-largest town in Neosho County, it had houses, streets, a schoolhouse, shops, and a Main Street. There were two sawmills within a mile of the town.

At first, its growth was somewhat rapid and encouraging. At one time, it was second in size and importance among the towns of Neosho County. At that time, it had several stores, a hotel, two blacksmith shops, a shoe and harness shop, and several good residential buildings.

Jacksonville was a religious community with three organized churches — Methodist, United Brethren, and Presbyterian, but it never had a church building. Instead, people met in groups in private homes and other structures. Later, a letter in the Neosho Valley Eagle, May 9, 1868, stated, “In Jacksonville, there we have a sermon every Sunday and often two.” The same issue also mentioned that the Methodists started a movement to erect a church in the fall of 1868, but the church was never built.

The Neosho Valley Eagle, the first newspaper in the county, was started here on May 2, 1868, by B.K. Land. In its issue of May 9, the editor wrote:

“The town is but little over a year old and is improving rapidly, having a little less than 600 population. There are six stores, a cabinet shop, carpenter and blacksmith shops, and boot and shoe shops, all of which give the place a lively appearance. We have a hotel which would do credit to larger towns, besides a good post office.

It is beyond doubt the best in all of south-eastern Kansas for grazing and agricultural purposes. For many miles around Jacksonville, the county is not surpassed for the beauty of location and richness of the soil, the black sandy soil ranging from two to five feet in depth. The immediate vicinity is abundantly supplied with good timber and stone for excellent quality building purposes.”

The newspaper didn’t stay long, moving to Erie on October 24, 1868.

In the 1870s, Jacksonville was a bustling town with ambition for being the county seat. The town was a centralized meeting point for settlers in the land grant fights in the Cherokee Neutral lands in Crawford and Cherokee Counties, between the settlers and James F. Joy’s Border Tier Railroad, and for settlers on the Osage Ceded Lands in Neosho and Labette Counties, in their fight for land claims against the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway. At that time, Jacksonville had several stores, two or three blacksmith shops, a sawmill, a brick manufacturing plant, at least two hotels, and two doctors.

In 1874, much excitement occurred in this small town when a man named John Pierce was lynched. Some time previously, Anthony Amend moved his family from Missouri to Jacksonville. His 22-year-old daughter Ann Amend married John Pierce, a school teacher, and the couple had two sons.

On March, 26. 1874, 52-year-old Anthony Amend is shot dead by his son-in-law in an argument. A newspaper report in the Fort Scott Monitor reported, “A man named John R. Pearce and his father-in-law, Anthony Amend, met in McCaslin’s store. They shook hands, and afterward, Pearce called Amend out of the store to talk to him. Pearce then asked Anthony Amend if he had been circulating reports that he abused his wife and child. Amend said that he had not but that the same was true. Pearce told him to take the statement back or “take that,” presenting a revolver. Amend refused to retract when Pearce discharged two barrels of the revolver, both balls hitting the breast near the heart. The first ball passed through Amend’s body and into the store. This was about two in the afternoon. Amend lingered in great agony for four or five hours when he died.”

John Pierce was reported as wearing his gun at all times, including in the classroom as he taught his students, and was described as an excessive talker who raved in a rambling, roundabout manner.

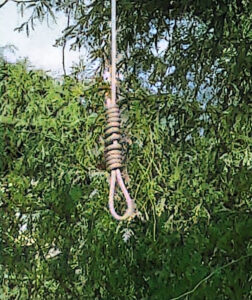

The shooting was witnessed by Anthony’s son, Homer, who would have been about 16 years old at the time. After the crime, Pierce vanished and headed toward the timbers, where he swam the Neosho River and was finally caught by three pursuing men. John Pierce was then taken to his one-room schoolhouse, where he was held in a makeshift jail by a vigilance committee known locally as the “Wigglers.”

Late in the night, the lights suddenly went out in the building, and as many as 100 men appeared on the scene. They put a rope around Pierce’s neck and drove him in a wagon to a spot on Hickory Creek just west of town. Under an oak tree with a projecting limb, about 12 feet from the ground, the men threw the rope over the limb and drove the wagon from under him. He hung there all night, his feet almost touching the ground, until about ten o’clock the next day when his father cut him down. John Pierce was initially buried in the Jacksonville Cemetery.

Several prominent men of Jacksonville were suspected of being “Wiggler” vigilantes and having been complicit in the lynching of John Pierce. Although a trial was eventually held at Osage Mission, with three men as defendants, the trial had no legal outcome. The trial ended when about 100 men rode up and hitched their horses outside the courthouse. “When they did so, the lawyers and judge disappeared out of the back, and the trial ended.

When the town flourished, a special carrier made trips between Jacksonville and Osage Mission (St. Paul). In 1878, H.C. Owens of Jacksonville, the carrier, was awarded the contract at $399 per year. Stagecoach runs and settlement trails also helped the town grow.

The coming of the first railroad, a narrow gauge line in the eastern part of Neosho County with a station at Osage Mission, stopped the growth of Jacksonville. “When the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad was built west from Arcadia, Kansas in 1879, it passed three miles south of Jacksonville, and the towns of McCune and Strauss were established. Soon, most of the Jacksonville businesses moved to McCune, and in a few months, little was left of Jacksonville except the abandoned schoolhouse and the old cemetery.

By the early 1880s, little was left of the town except a post office in a lonely farmhouse.

On December 17, 1881, the abandoned school in Jacksonville, Kansas, was destroyed by fire. In 1882, the Humboldt-Baxter Springs stage line began delivering mail to Baxter Springs in Cherokee County rather than to Jacksonville. Afterward, the Jacksonville post office, with postmistress Catherine A. Logan, closed on November 27, 1882.

Today, the old townsite is plowed over for farmland, and the only thing left of it is the forgotten, unkempt, and overgrown old Jacksonville Cemetery, which is on private land. Some graves remained as of the 1980s, but most were removed to McCune. Jacksonville was about 15 miles southeast of St. Paul, Kansas. Its main road through town was 27000 Road west of York Road, passing on the south side of the town square.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2024.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Neosho County

Sources:

American Journeys

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Ghosttowns.com

Roberts, Dane; Old Jacksonville Townsite, Kansas State University, March 2012.