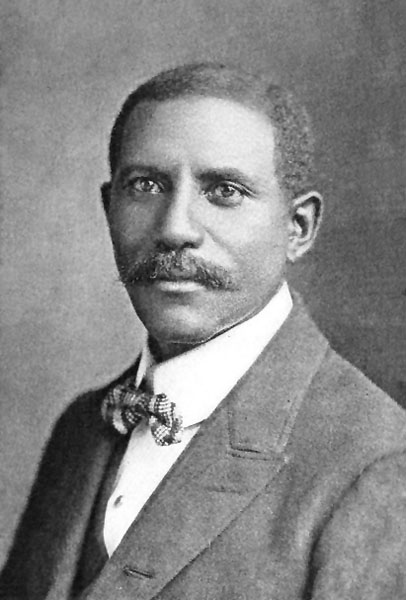

Junius George Groves was an African American farmer and entrepreneur remembered as one of the wealthiest black Americans of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Junius was born a slave on April 12, 1859, to Martin and Mary Anderson Groves in Green County, Kentucky. Groves could only attend school for a few months each year as a child but developed a lifelong thirst for learning.

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, made him and his parents free a few years later.

Groves came to Kansas as an Exoduster in 1879 with 90¢ in his pocket. At age 19, he first worked at the meat packing houses in Armourdale, Kansas, and later moved to Edwardsville, Kansas, where he engaged in sharecropping.

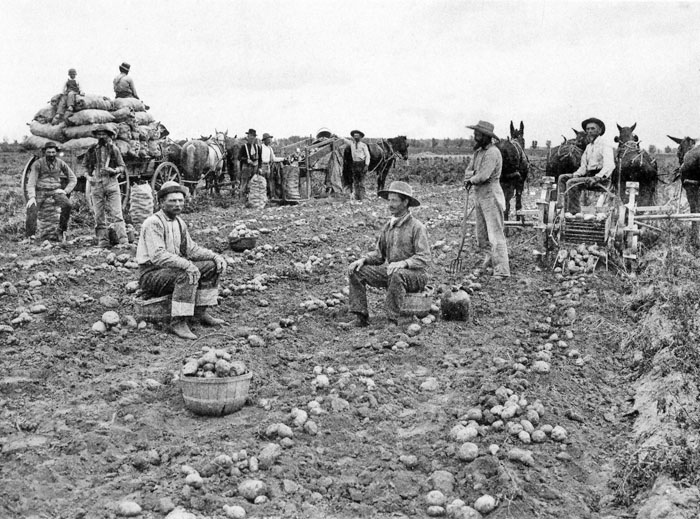

Groves started the potato farming business when he share-cropped nine acres of land with farmer Jake Williamson. On that first farm, Groves planted both sweet and Irish potatoes. Williamson initially paid Groves 40 cents a day. After three months, he was making 75 cents a day. Soon Groves received one-third of the crops farmed on Williamson’s nine acres. In the first year of sharecropping, Groves made $125, which he then used to buy land of his own, a milk cow, and other investments toward his next crop.

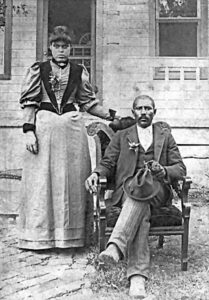

In 1880 he married Matilda Emily Stewart from Kansas City, Missouri, and she worked by his side in the field. The couple would eventually have 14 children, 12 of which survived.

After his second year, Groves had 20 acres, and in his third year, he bought ten more acres and a cabin across from Lake of the Forest. That same year he bought 80 acres from a Native American for $500. Subsequent acquisitions included a sawmill, and five adjoining farms, making his total holdings more than 760 acres. Besides potatoes, he had apple, peach, and pear orchards, and a vineyard. His children worked along with Junius and Matilda on the farm and holdings.

He founded the Pleasant Hill Baptist Church Society in 1886 and was elected secretary of the Kaw Valley Potato Association in 1890.

In 1891, the Historic Times, a newspaper in Lawrence, Kansas, reported that H. P. Ewing of Loring, Kansas, and Junius G. Groves were two of the wealthiest Black men in Kansas.

In 1895, the Kansas State Agricultural Census recorded Groves as owning 400 acres of potatoes, 170 acres of apple trees, 160 acres of corn, and 50 acres of cherry trees. He also owned 21 cows, nine horses, and 24 hogs.

Besides producing potatoes on his farms, by 1900, Groves was buying and shipping potatoes, fruits, and vegetables, including corn, cabbage, and carrots, extensively throughout the United States, Mexico, and Canada. The family also owned the Cross Road Grocery Store in Edwardsville, invested in mines in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Mexico, had stock in Kansas banks, and held a majority interest in the Kansas City Casket and Embalming Company. Junius Groves co-founded the State Negro Business League and later served as its President.

In the early 1900s, he founded the community of Groves Center near Edwardsville, selling small tracts of land to African American families. He also built a golf course for African Americans, possibly the first in the United States. His name is on the original deed of the historic Edwardsville Colored Cemetery, which some in the city refer to as the Stoney Point Cemetery. He was one of the founders of the Franklin Cemetery, where he and many of his family are buried.

In 1902, Groves was named by the U.S. Dept of Agriculture the “Potato King of the World” for beating his closest competitor on the planet by 11,500 bushels. His optimized potato growth led to producing 721,500 bushels of the crop in a single year.

His vast financial success, analyzed in Booker T. Washington’s The Negro in Business in 1907, was utilized to help combat racism by providing economic opportunities for other black Americans. Washington had high praise for him, describing Groves as “our most successful Negro farmer.” Much of Groves’ success was due to his forty-six years of devotion to the science of agriculture

Junius Groves was one of the wealthiest African Americans in the nation by the first decade of the 20th century. His holdings were estimated to be worth $80,000 in 1904, and by 1905, his holdings included more than 500 acres. By 1915, His holdings were estimated to be worth $300,000.

At the height of his success, he had constructed a 22-room mansion equipped with the latest comforts of the era for $22,000. The 22-room brick home had electric lights, two telephones, and hot and cold running water in all the bedrooms. The sprawling home was constructed of red brick, trimmed in white stone, with a roof of red tile, and featured oak doors. It was the largest in the area. Due to his shipping quantity, the Union Pacific Railroad built a spur to his property.

At that time, he was wealthier than most whites and undoubtedly encountered racism. His response, however, was to provide economic opportunities to blacks and whites. Grove employed up to 50 mostly black laborers during the busy farming season.

He was Vice President of the Sunflower State Agricultural Association in 1910.

Groves suffered financial setbacks in the 1920s, including a loss of around $90,000 in a cattle venture. Groves built three mansions, all burning down “mysteriously,” the last in 1968. He was a well-known philanthropist and, every year, gave a portion of his yearly crop to a local hospital.

Junius Groves died of a heart attack at the age of 66 in Edwardsville on August 17, 1925. One local newspaper reported his funeral was the “largest ever in Edwardsville,” with over 3,000 people attending. He was buried in Franklin Cemetery, Grinter Heights, Wyandotte County, Kansas. His wife Matilda survived him, dying on August 28, 1930, at the age of 66.

In 2007, Groves was honored by his descendants, the Votow Colony Museum, an organization honoring the Exodusters and their descendants, and the City of Edwardsville. He was also inducted into the Bruce W. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center Hall of Fame in nearby Kansas City, Missouri.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated June 2023.

Also See:

Sources:

Black Listed Culture

Black Past

Find-a-Grave

Kansaspedia

Wikipedia