Bill Bader & Louis Laubner saloon in Dodge City, about 1895. (colorized)

From its earliest territorial and statehood days, the temperance question was an engaging topic in Kansas. The Kansas Territorial Legislature of 1855 enacted a law entitled “An act to restrain dramshops and taverns and regulate the sale of intoxicating liquors.” It provided that a special election should be held on the first Monday of October 1855. Every two years thereafter, in each municipal township in each county and each incorporated city or town in the territory, to take a vote of the citizens upon the question whether dramshops and tavern licenses should be issued for the two years following the election.”

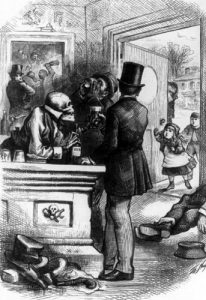

Dramshop.

The vote was to be by ballot, either “In favor of dramshops” or “Against dramshops.” Before a license could be given to tavern keepers, grocers, or other liquor sellers, a majority vote had to be cast by each municipality in favor of the measure. Most householders were required to petition for the vote to be held.

Penalties for selling any spirits, wines, or other intoxicating liquors contrary to law included a fine of $100 for the first offense and every second or subsequent offense not less than $100 and imprisonment in a county jail not less than five and not more than 30 days. Selling to a slave without the sanction of his master, owner, or overseer, or selling liquor on Sunday also subjected the offender to these same penalties as well as a forfeiture of their license. Licensees were also required to give a bond of $2,000 and not to keep a disorderly house.

Further action on the liquor question was taken by the Legislature of 1859, which included an act “to restrain dramshops and taverns and regulate the sale of intoxicating liquors.” It provided that a county business or city should grant no license unless most householders signed the petition requesting the dramshop, tavern, or grocery license in the township, county, or ward where the license was sought. However, all incorporated cities containing 1,000 or more inhabitants were exempted from this act; such cities possessed full powers to regulate licenses for all purposes and dispose of the proceeds. This law fixed the tax upon the dramshop keeper at not less than $50 nor more than $500 for 12 months. The fine for selling liquor without a license was not to exceed $100 for the first offense. The fine should not be greater than $100 for the second and subsequent offenses. Still, the offender might be indicted for a misdemeanor and fined not less than $500 and imprisoned in the county jail for not less than six months. It was made a misdemeanor to sell liquor on Sunday, the Fourth of July, to anyone known to be in the habit of getting intoxicated or to any married man against the known wishes of his wife. All places where liquor would be sold in violation of this act were declared nuisances. In addition, damages could be recovered by every wife, child, parent, guardian, employer, or another person who should be injured in person, property, or means of support by any intoxicated person or in consequence of intoxication, and a married woman could sue as a single person.

In the Constitutional Convention of 1859, there was some discussion about incorporating a prohibitory measure concerning liquor in the Constitution. John Ritchie of Topeka suggested the following resolution: “Resolved, that the constitution of the state of Kansas shall confer power on the legislature to prohibit the introduction, manufacture or sale of spirituous liquors within the state.” On July 23rd, 12 days later, from Burlingame, H.D. Preston offered this section: “The legislature shall have the power to regulate or prohibit the sale of alcoholic liquors, except for mechanical and medicinal purposes.” In the end, however, no prohibitory measure was included in the constitution at that time.

The temperance sentiment continued to increase and was very strong by 1867. Lecturers from the East addressed the subject, enlarging and stimulating the temperance feeling throughout the state. In 1869, all the territorial and state laws of Kansas were revised, and the so-called Dramshop Act went into effect on October 31, 1869, providing in part:

“Before a dramshop, tavern or grocery license shall be granted to any person applying for the same, such person, if applying for a township license, shall present to the tribunal transacting county business, a petition or recommendation signed by a majority of the residents of the township, of 21 years of age or over, both male and female, in which such dramshop, tavern or grocery is to be kept; or if the same is to be kept in any incorporated city or town, then to the city council thereof a petition signed by the majority of the citizens of the ward of 21 years of age, both male and female, in which said dramshop, tavern or grocery is to be kept, recommending such person as a fit person to keep the same, and requesting that a license be granted to him for such purpose; provided that the corporate authorities of cities of the first and second class may by ordinance dispense with petition mentioned in this section.”

The act further provided, as a penalty for selling liquor on Sunday or the Fourth of July, a fine of not less than $25 or more than $100 and imprisonment from 10 to 30 days. It was also illegal for a person to become intoxicated or sell alcohol to habitual drunkards or minors.

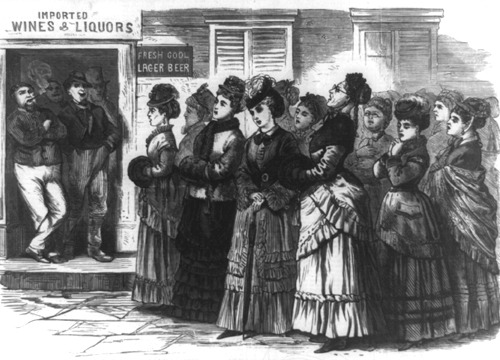

Ladies singing in barroom during the Temperance Movement, Leslie’s Illustrated newspaper, 1874.

The years 1861 to 1879 were fraught with an ever-increasing tendency toward Prohibition. A few temperance workers labored most industriously to change public opinion regarding open traffic in liquor. This new public opinion was in great measure due to the crusade made against liquor by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Prohibition meetings were held in all the principal cities of the state years before the amendment to the constitution was adopted. Drusella Wilson, the first president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, traveled 3,000 miles in a private conveyance, making speeches, holding mass meetings, and “soliciting signatures to a petition to be presented to the legislature.”

She set the women working all over the state to work more efficiently, organizing unions to be more efficient. That year, she organized over 100 unions and presented the first petition to the Legislature, the largest one ever presented.

The women worked faithfully, but when election day came, they also turned out all over the state and worked all day, urging up indifferent and negligent voters and supplying refreshments. They held prayer meetings in the churches and sang church songs every hour to remind the voters that the women were praying for protecting the homes and the boys.

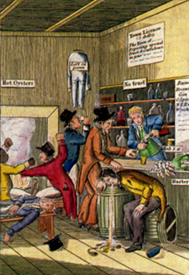

In his message to the Legislature on January 14, 1879, Governor John P. St. John included a section on temperance. He said in part: “The subject of temperance, in its relation to the use of intoxicating liquors as a beverage, has occupied the attention of the people of Kansas to such an extent I feel it my duty to call your attention to some of its evils and suggest, if possible, a remedy. Much has been said of late years about hard times and extravagant and useless expenditures. In this connection, I desire to call your attention to the fact that here in Kansas, where our people are at least as sober and temperate as are found in any of the states in the West, the money spent annually for intoxicating liquors would defray the entire expenses of the state government, including the care and maintenance of all the charitable institutions, agricultural college, normal school, state university, and penitentiary… Could we but dry up this one great evil that consumes annually so much wealth and destroys the physical, moral and mental usefulness of its victims, we would hardly need prisons, poorhouses, or police.”

Governor St. John was an ardent and influential champion of the temperance cause. Through his influence and that of other active and sympathetic temperance workers, the Legislature of 1879 passed and submitted to the people of Kansas a joint resolution providing an amendment to the constitution, as follows: “The manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors shall be forever prohibited in this state, except for medical, scientific and mechanical purposes.” The amendment came before the people at the polls on November 2, 1880, and out of a total vote of 176,606, it was carried by a majority of 7,998. At the next Republican state convention, St. John was re-nominated for governor upon “a platform pledging the party to the policy of Prohibition of the liquor traffic” and made a fight on that issue before the people.

In his message to the Legislature of 1881, he stated that “This amendment being now a part of the constitution of our state, it devolves upon you to enact such laws as are necessary for its rigid enforcement. A few citizens today will not admit that dramshops are a curse to any people. More crime, poverty, misery, and degradation flow from them than from all other sources combined. The real difference in opinion about them is not about whether they are evil or a blessing, but rather about what course they take.

Some have contended that they should be licensed, but it seems that if they are evil, no government should give them the sanction of the law. They should be prohibited as we prohibit all other acknowledged evils. It has been urged as an argument in favor of licensing dramshops that, under that system, significant revenue is derived. Granting this to be true, I insist we have no right to consider the question of revenue at a cost of the sacrifice of principles. All the revenue ever received from such a source will not compensate for a single tear of a heartbroken mother at the sight of her drunken son as he reels from the door of a licensed dramshop… The people of Kansas have spoken upon the question in a language that cannot be misunderstood. By their verdict, the license system related to the sale of intoxicating liquors as a beverage has been blotted from the statute books of the state. We now look to the future, not forgetting that it was here on our soil where the first blow was given that finally resulted in the emancipation of a race from slavery. We have now determined upon a second emancipation, which shall free the body and the soul of man. Now, as in the past, the civilized world watches Kansas and anxiously awaits the result. No step should be taken backward. Let it not be said that any evil exists in our midst, the power of which is greater than the people.”

The Legislature, representing the temperance element of the state, on February 19, 1881, passed an act of 24 sections prohibiting the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors except for medical, scientific, and mechanical purposes and regulating the manufacture and sale thereof for such excepted purposes.

It also made it unlawful to give away liquor, and for a person to become intoxicated, the fine was $5 or imprisonment in county jail from one to ten days. The passage of this strict Prohibition law started propagating the idea of temperance, although its effect on liquor traffic was not immediately recognized. In different parts of the state, vigorous prosecutions were instituted. The Prohibition policy had many enemies who believed the constitutional amendment was a mistake. Among these was Governor George W. Glick, who succeeded Governor St. John in 1883. In his message to the Legislature, he dealt with the subject of Prohibition and the operation of the law. Glick tried hard to modify the law, but it fell on deaf ears and was not changed. The state legislatures of later years amended and supplemented the original enactment.

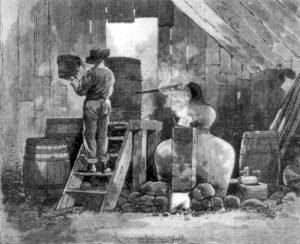

Carry Nation fights the war against alcohol.

In the early 1890s, the Agora Magazine conducted a symposium on the condition of Prohibition in Kansas, which had been in effect for over ten years. The consensus was that the public sentiment was constantly increasing in its contempt for liquor traffic. Many men who voted against Prohibition in 1880, after viewing the results of the law only partially enforced, were heartily convinced in 1890 that Kansas was far better off without open saloons. The churches, the State Temperance Union, and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union continued to promote the movement.

A movement toward enforcement of state laws became a policy of many politicians seeking office in Kansas and elsewhere and a tendency toward cleanliness in political and municipal affairs.

The actual enforcement of the Prohibition law began in about 1907. Before that time, the officials were somewhat lax in their duties, and many drugstores were practically dramshops.

The county attorneys and attorney general planned to make Kansas thoroughly “dry” and systematically closed up the places selling liquor. In 1909, the laws were revised and strengthened, with a significant change in the withdrawal of druggists’ permits to sell liquor for medical, scientific, and mechanical purposes.

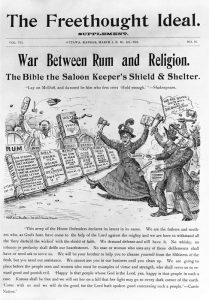

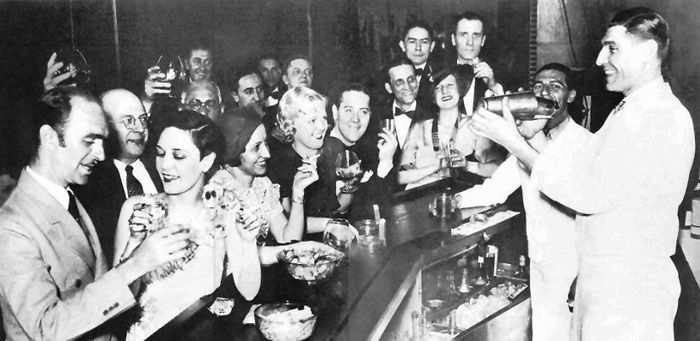

The power of public opinion regarding Prohibition soon spread throughout the nation, bringing Prohibition to other states and the entire nation in 1919. Called the “Noble Experiment,” the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol for consumption were banned across the country. Though its many supporters were sure that Prohibition would lead to a better United States, they were not prepared for the many criminals it would create. Bootlegging and illegal liquor distribution became rampant, and the government was unprepared to enforce the laws. In fact, by 1925, there were anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000 speakeasies in New York City alone.

During the Great Depression, Prohibition became increasingly unpopular, especially in large cities. On March 23, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an amendment allowing the manufacture and sale of certain kinds of alcoholic beverages. On December 5, 1933, the National Prohibition was overturned. Each state then had the opportunity to present the issue to its citizens. On November 6, 1934, Kansas voters rejected a proposed constitutional amendment authorizing the Legislature to regulate and tax liquor. Therefore, though alcohol consumption was still illegal in Kansas, alcoholic beverages were produced, transported, and used throughout the state with little law enforcement.

In 1937, the Kansas Legislature enacted a law that allowed beer (cereal malt beverages) with an alcoholic content of 3.2% or less to be sold in the state for both on and off-premise consumption and set the drinking age at 18. The prohibition of liquor in Kansas continued into the 1940s, but there was little law enforcement again.

1920s Speakeasy.

However, in 1946, Ed Arn became the state’s Attorney General, and he planned to end the hypocrisy and enforce the laws on the books.

Several distinguished Kansans subsequently undertook an effort to end state Prohibition, which led to a proposal to end Prohibition being placed on the General Election ballot in November 1948, which passed.

This amendment authorized the Legislature to “regulate, license and tax the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquor, and regulate the possession and transportation of intoxicating liquor.” The amendment also “forever prohibited” the open saloon, which meant that packaged liquor could be authorized and regulated. Still, the sale of liquor by the drink, meaning the sale of alcoholic beverages in restaurants, bars, or public places, was prohibited.

The following year, the Legislature enacted the Liquor Control Act, which created a system of regulating, licensing, and taxing package sales, and the Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control to enforce the act. The drinking age for alcoholic liquor was set at 21, while the drinking age for cereal malt beverages remained at 18.

In 1965, Kansas approved the Private Club Act, which allowed liquor to be drunk only in private clubs.

The new law required members to pay a $10 fee and wait 10 days from the date of application before they could be served. It also required people to purchase a separate membership for each club they wanted to drink at. The situation was particularly difficult for travelers from other states who were often perplexed and disappointed at Kansas liquor laws.

In 1970, voters had the opportunity to pass a constitutional amendment to legalize liquor by the drink; however, the proposition lost by 0.8 percentage points. The on-premise problem persisted.

In 1978, the Legislature authorized private clubs that were restaurants (defined as establishments deriving more than 50% of their gross receipts from the sale of food) to sell liquor by the drink. However, the courts struck down the law, which was set to take effect in counties where voters approved such sales in the 1978 election.

More provisions were passed in the 1985 Legislature that would profoundly impact the sale of alcoholic beverages in Kansas. These included raising the drinking age for 3.2 beer from 18 to 21, prohibiting “happy hours,” and once again allowing Kansas voters to decide whether to allow the sale of liquor by the drink.

After decades of battling, the voters finally passed liquor by the drink in the 1986 election by a 59.9% to 40.1% margin. Bars and restaurants in the 36 counties approving the measure could then legally sell liquor to the public for the first time since 1880.

By 1998, 11 counties voted in liquor by the drink with no food requirements, while numerous others relaxed the food requirements. Since then, numerous other counties have followed suit, and in some, the “no sale of alcohol on Sundays” policy was eliminated, allowing liquor sales.

Still, a few rules were baffling to visitors—for example, liquor, except for beverages under 3.2%, could only be sold in retail liquor stores, which were not allowed to sell food, cigarettes, ice, etc.

Finally, the law changed on April 1, 2019, allowing convenience and grocery stores to sell alcoholic beverages with up to 6% alcohol. Liquor stores could sell other items, such as beer. So, if visitors would like to buy a bottle of vodka and a six-pack of beer, they can only do so in a liquor store.

In 2021, 39 Kansas counties had no food sales requirement for liquor by the drink, 63 counties required a 30% food sales requirement, and three counties still did not allow liquor by the drink. This means that visitors can only purchase cocktails at restaurants that serve food in counties with a food requirement. In those counties that do not allow liquor by the drink, visitors can purchase liquor and beer in stores, but there are no bars.

Throughout Kansas’s history, the regulation of alcoholic beverages has been a source of controversy, with change efforts often producing heated debates.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2026.

Also See:

Speakeasies of the Prohibition Era

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Kansas Department of Revenue Alcoholic Beverage Control