Nearly three centuries passed from when Hernán Cortez led the Spaniards into Mexico until Kansas became a part of the United States. During those years, Spanish settlements had increased in number until, at the time of Zebulon Pike’s expedition to Mexico included most of what is now California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado.

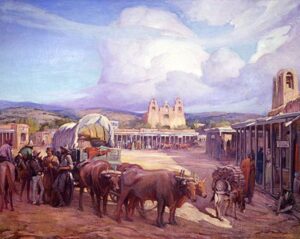

Old Santa Fe. Santa Fe, New Mexico, said to be the second oldest city in the United States, was the most important point on the northern frontier of Mexico. In those days, it had about 2,000 inhabitants, practically all Spaniards, and they lived in little adobe houses arranged around a public square after the manner of Spanish cities.

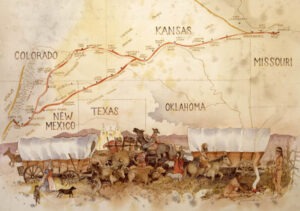

Origin of the Santa Fe Trail. The “Great American Desert” lay between Santa Fe and the settlements of the western border of the United States. But Captain Pike’s interesting descriptions of the wealth and resources of the Spanish country stirred up enthusiasm, and Americans began to make their way across the plains to trade with the Spaniards. Santa Fe soon became an important trading point for all of northeastern Mexico. On their journeys to the Spanish city, the traders wore a pathway crossing the length of Kansas. This pathway came to be called the “Santa Fe Trail.”

William Becknell on the Santa Fe Trail.

Captain William Becknell the First Trader. Although a few earlier trips were made, the trade with Santa Fe began in the year 1822 with the journey of Captain Becknell of Missouri. He had started out the year before to trade with the Indians and had gone on with a party of Mexican rangers to Santa Fe, where he sold his small supply of merchandise so profitably that he decided to try again on a larger scale. In 1822 he took about 30 men and $5,000 worth of merchandise. His success encouraged others, and regular trade with Santa Fe was soon established.

Merchandise Carried on Pack Mules. For several years most of the transportation along the Trail was done with pack mules. A caravan of pack mules usually numbered from 50 to 200, each animal carrying about 300 pounds of merchandise. From the earliest times, the Mexicans had used pack mules for transportation and were skilled in handling them. For this reason, the American traders usually employed Mexicans for the work of the pack train. A mule train’s average travel rate was 12 to 15 miles daily. Since the Trail was nearly 800 miles long, 50 to 60 days were required for the trip.

Wagons Used on the Trail. The first time wagons were used was in 1824, when a company of traders left Missouri with 25 wagons and a train of pack mules. This experiment was so satisfactory that wagons soon became general, and mules were used less and less as pack animals.

The Traders and the Indians. Travel over the Santa Fe Trail rapidly increased, and the history of those days is filled with stories of exciting adventure, danger, privation, and deeds of courage. The source of greatest danger and excitement was the Indians, for they did not take kindly to the white men’s use of their hunting grounds. For several years the traders crossed the plains in small parties, each man taking only $200-$300 worth of goods, and they were seldom molested. But peace did not last long. The Indians soon learned more about the journeys of the traders and how to estimate the value of their stock. Also, many of the traders considered every Indian a deadly enemy. They killed all that fell into their power simply because some wrong was known to have been committed by Indians. This treatment tended to stir up the red men’s hatred and make them watch every opportunity for revenge.

An example of the enmity between the Indians and the traders may be seen in an occurrence of 1828. Two young men went to sleep on the bank of a stream a short distance from their caravan and were fatally shot, it was supposed, with their own guns. When their comrades found them, one was dead, and the other died by the time the caravan reached the Cimarron River, about 40 miles farther. During the simple burial ceremonies, a party of six or seven Indians appeared on the other side of the river. These Indians probably knew nothing of the crime committed, or they would not have approached the white men. Some of the men took this view, but against their advice, the others fired and killed all of the Indians but one, who escaped carrying the news to his tribe. The Indians of the wronged tribe then followed the caravan to the Arkansas River, where they robbed the traders of nearly 1,000 head of horses and mules. Other robberies and murders followed until it became necessary for the traders to petition the National Government for troops. The next year, soldiers escorted the caravan nearly to the Cimarron River. Government protection was furnished again in 1834 and 1843. In other years, the traders fought their own way, but the day of small parties was over. For mutual protection, the traders banded together. A single big caravan started out each spring as soon as the grass was sufficient to pasture their animals and returned in the fall.

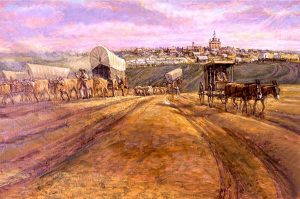

The Starting Point of the Traders. For many years, the city of Franklin, on the Missouri River, was the starting point of the traders, where they purchased their goods and outfits. Later, Independence, Missouri, and Westport, now a part of Kansas City, became the emporium of the Santa Fe trade. The tourists and traders began to gather about the first of May for the journey that would begin near the middle of that month.

Supplies Taken. Ordinary supplies for each man were about 50 pounds of flour, 50 pounds of bacon, ten pounds of coffee, 20 pounds each of sugar, rice, beans, and a little salt. Anything else was considered an unnecessary luxury and was seldom taken. The buffalo furnished fresh meat for the travelers.

Teams and Wagons. After the first few years, horses were little used on the Trail except for riding. A wagon was usually drawn by eight mules or oxen, though some larger ones required ten or twelve. The large wagons often carried as much as 5,000 pounds of merchandise and supplies. The wagon loading for a nearly 800-mile journey was a very particular piece of work.

Council Grove the Meeting Place. Although the traders banded together in one big caravan, they did not all start from the same place or at the same time. The Kanza and Osage Indians seldom committed worse deeds than petty thievery, and the more warlike Comanche and Pawnee did not often appear along the first 200 miles of the Trail. Council Grove, Kansas, about 150 miles west of Independence, was where all the wagons united to form a caravan.

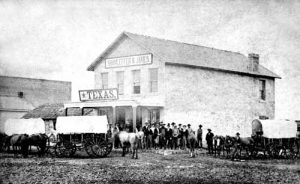

Council Grove consisted of a strip of fine timber along the Neosho Valley in those days. It is said to have been named in 1825 by the United States Commissioners who met on this spot some Osage Indians, with whom they made a treaty for the right of way for the Santa Fe Trail. About 1850, a blacksmith shop and two or three traders’ stores were established at Council Grove, and this place became “the last chance for supplies” for westbound travelers.

Journeys of Josiah Gregg. We can not get an idea of those days in a better way, perhaps, than by following an account of one of the caravans. Josiah Gregg, who crossed the prairie eight times, has left a very interesting record of his experiences. Many of the following facts are taken from his account of the journey of 1831.

Organization of the Caravan. There were 200 men and nearly 100 wagons for this particular trip, with a dozen smaller vehicles and two carriages carrying cannons. The total value of the merchandise was about $200,000. For so large an undertaking it was, of course, necessary to have some organization. According to custom, they elected officers and adopted a set of rules. The head man was the “Captain of the Caravan,” who directed the travel order, selected the camping grounds, and performed many other duties of a general nature. The wagons were divided into four groups, each under the charge of a lieutenant, who selected crossings and superintended the “forming” of the camp. The men were well-armed with rifles, shotguns, and an abundant supply of pistols and knives.

The Starting of the Caravan. When the time came to start from Council Grove, the command “Catch up! Catch up!” sounded by the captain and passed on to all the groups, started a scene of hurry and uproar as the teamsters vied with each other to be first to shout “All’s set!” After a period of shouting at animals, the clanking of chains, and the rattling of harnesses and yokes, all were ready. The command “Stretch out!” was given, and the line of the march began.

The Country West of Council Grove. Council Grove seemed to form the western boundary of the rich, fertile, and well-timbered country. From here westward, the streams were lined with little timber growth, and ! much of that was cottonwood. The country was mostly prairie, with the vegetation gradually becoming more scarce. The traders usually lashed a supply of logs under their wagons for needed repairs, for Council Grove furnished the last good wood they would pass. Westward from Council Grove, not a single human habitation, not even an Indian settlement, was to be seen along the entire route.

Buffaloes Sighted. Soon after leaving Council Grove, the traders began watching for buffaloes, and when a small herd was sighted, it created much excitement. About half the men had never seen these animals before. All the horsemen rushed toward the herd, and some drivers even left their teams and followed on foot. Pawnee Rock. After a few more days of travel, during which nothing more serious happened than a few false alarms of Indians, they reached the Arkansas River.

Another day’s travel over a level plain brought them in sight of Pawnee Rock, a great rock standing on the plains near the Big Bend of the Arkansas River and a landmark known from one end of the Trail to the other. The surrounding country was not occupied by any tribe of Indians but was claimed by all of them as a hunting ground, for it was a fine pasture for buffalo. For many years it had been the scene of bloody battles between different tribes. The Rock afforded an excellent hiding place and retreat. Since the old Trail passed within a few yards of it, this became a dreaded spot for the traders, for at this point, they seldom escaped a skirmish with the Indians. The Rock probably received its name from some of the bloody deeds of the Pawnee, who were especially connected with these scenes.

Forming Camp. When the caravan camped at Ash Creek, the traders found a few old moccasins scattered around and some campfires still burning, which seemed to indicate the near presence of Indians. They had marched in two columns up to this point, but after crossing Pawnee Fork, they formed four lines for better protection in case of attack. In camp, the wagons were arranged in a hollow square, each line forming a side. This provided an enclosure for the animals and a fortification against the Indians. Ordinarily, the campfires were lighted outside the square, the men slept on the ground, and the animals were picketed near.

The Caches. The next important stopping place was The Caches, near the present site of Fort Dodge. A group of pits in the ground marked this spot from the surrounding country. Several years before, a small party of traders had attempted to go to Santa Fe in the fall. By the time they reached the Arkansas River, a heavy snowstorm had forced them to take shelter on a large island, where they were kept for three months by the severe winter. During this time, most of their animals perished. When spring came, having no way to carry their goods, they made some caches where they stored their merchandise until they could bring mules to haul it to Santa Fe.

The Trail Divided into Two Routes. At Cimarron Crossing, the Trail divided and did not reunite until within a few miles of Santa Fe. The southern route was shorter but meant crossing 50 miles of desert before reaching the Cimarron River. In all that stretch of a level plain, there was no trail, landmark, or stream of water. Travelers sometimes lost their way in this desert, and unless they had prepared for this part of the journey by taking along a sufficient supply of water, they perished of thirst.

An Experience with Indians. This caravan decided to take the southern route. A band of Indians soon appeared, carrying an American flag as a token of peace. They talked with the traders using signs and told them there were immense numbers of Indians ahead. A little later, a band of warriors appeared and threatened to fight. There was great excitement as the caravan prepared for battle, and the Indians continued to pour over the hills. But there was no fighting, for the chief came forward with his “peace pipe,” from which the captain took a whiff. The warriors were ordered back to rejoin the long train of women and papooses who were following with the baggage. There were probably 3,000 Indians in this party, and they moved down into the valley and pitched their wigwams. The traders felt sure that since the women and children were along, the Indians would not be hostile, and they, therefore, formed their camp a few hundred yards away. The Indians gathered around to gaze at the wagons, for it was probably the first time most of them had ever seen such vehicles. Some of them followed to the next camp, and the next day a large number of them gathered around the caravan. This sort of thing continued until the traders made up a present of $50-$60 worth of goods to “seal the treaty of peace.”

Their First News. Some days later, the caravan met a Mexican buffalo hunter. He told the traders the news from Santa Fe, the first they had heard since the return of the caravan of the year before. Today Kansas City and Santa Fe are little more than 24 hours apart by rail, and we read the latest news from both places in the morning and evening papers.

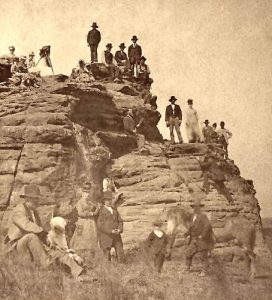

Round Mound. Round Mound, standing nearly a thousand feet above the level of the surrounding plain in what is now New Mexico, was one of the landmarks along the Trail. At that point, the caravan had completed about three-fourths of the journey to Santa Fe. As they approached the Mound, some of the party decided to ascend it. They felt certain that it could not be more than half a mile away, but they had to go fully three miles before reaching it. This remarkable deception in the distance is characteristic of the West. Nothing of particular note occurred from Round Mound to the journey’s end.

Arrival at Santa Fe. The arrival of the caravan at Santa Fe was a source of excitement for both the traders and the city and was celebrated with much festivity. The traders had entered what was in those days a foreign country and had to pay duties on their goods at the custom house. Then came the business of selling these goods to those who had come in from the surrounding country to buy, after which the traders, or freighters as they were often called, prepared for the long return journey, planning to finish the round trip before the winter began. This was but one of many trips made over the Santa Fe Trail.

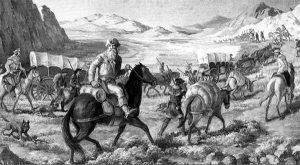

Travel Across Kansas During the 1840s. There was a war between the United States and Mexico in 1846-1848. The trouble between the two countries checked the Santa Fe trade between 1843 and 1850, but even under those circumstances, there was much travel across Kansas during the 1840s. There were four principal classes of travelers: soldiers, emigrants to Oregon, Mormons, and California gold seekers. The Soldiers. The war with Mexico broke out in 1846, and many United States soldiers were sent to that country by way of the Santa Fe Trail. This increased the travel across the prairies.

The Oregon Settlers. The remote unsettled region in the Northwest, known as Oregon, soon became the home of civilized people. In 1842 wagon trains of emigrants began to undertake the long and weary journey to that far-off country. Others soon followed, and during the next few years, many thousands of people settled in the Oregon country.

The Mormons. In those days, the Mormon Church had not been long established, but their beliefs had brought the Mormons into trouble with the people around them and with the Government, and they had been forced to move several times. The last time was in 1845, when they left Nauvoo, Illinois, and began the long and perilous journey to the valley of Great Salt Lake, in which region the main body of them remains today.

The “Forty-niners.” In 1848 a man named James Marshall, who was running a sawmill near the present site of Sacramento, California, discovered shining particles of gold in the mill race, and it was soon found that there were rich gold fields in that part of the country. The news spread, not rapidly as it would today, for there were no railroad or telegraph lines west of the Mississippi River and only a few east of it. Within a short time, the whole country and even Europe had heard of the California gold fields, and people from all parts of the world began to make their way to the Pacific coast. Some went by water, but more of them made the journey overland. Long lines of wagons, or prairie schooners as they were called, wound their way across the plains and over the mountains to California. It is estimated that 90,000 people passed through Kansas on their way to California during the two years 1848 and 1849, a few of them to gain wealth, but thousands to be disappointed, and many to perish on the way.

The Oregon Trail. The Oregon settlers, the Mormons, and the gold seekers entered Kansas at or near Atchison, Leavenworth, St. Joseph, or Westport, and moved toward the northwest, crossed the border into Nebraska, and went on across the mountains. The road worn by this westward-moving stream of emigrants was known as the Oregon Trail, though it was sometimes called the Mormon Trail and, more often, the California Trail. For 2,000 miles, the Oregon Trail stretched through an utter wilderness; every mile of it was the scene of hardship and suffering, of battle or death. It was one of the most remarkable highways in history.

It had several branches, and in many places, it followed different routes at different times. The largest number of travelers over this Trail entered Kansas at Westport and followed for a short distance on the Santa Fe Trail. Near the present town of Gardner stood a signboard on which were the words “Road to Oregon.” At this point, the two historic highways divided. It has been said that “never before nor since has so simple an announcement pointed the way to so long and hard a journey.”

Summary. The Santa Fe Trail was a great road about 775 miles long, beginning successively at the Missouri towns Franklin, Independence, and Westport and extending westward to Santa Fe. Four hundred miles of its length were in Kansas. Travel began in 1822 for the purpose of trading with Mexico. The first merchandise was carried on pack mules, but wagons began to be used in 1824. The traders experienced much trouble with the Indians, and in 1829 they began going together in big caravans for protection. The gathering place was Council Grove, where they organized and started. Some well-known sites along the Trail were Pawnee Rock, Ash Creek, Pawnee Fork, and The Caches. At Cimarron Crossing, the Trail divided. The northern branch followed the Arkansas River and crossed the mountains over practically the same route later followed by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. The southern branch was the cut-off across the desert. Another historic highway was the Oregon Trail, sometimes called the Mormon Trail and sometimes the California Trail. This Trail crossed the northeast corner of Kansas.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023. Source: Arnold, Anna E.; The State of Kansas; Imri Zumwalt, state printer, Topeka, Kansas, 1919.

Also See:

Kansas Santa Fe Trail Photo Gallery

The Santa Fe Trail Across Kansas