Garden City, Kansas, located on the Arkansas River in Southwest Kansas, is the county seat of Finney County. As of the 2020 census, the city’s population was 28,151. The city is home to Garden City Community College and the Lee Richardson Zoo, the largest zoological park in western Kansas.

In February 1878, James R. Fulton, William D. Fulton, and William’s son, L.W. Fulton, arrived at the present site of Garden City. They came, hunting wild horses and filing homesteads along the Arkansas River. The third town founder, John A. Stevens, was a young member of Fulton’s outfit and a buffalo hunter.

A year later, Charles Jesse “Buffalo” Jones came to Garden City for an antelope hunt in January 1879. He was a colorful character who earned the nickname “Buffalo” for his skills as a buffalo hunter. Before Jones returned home, the Fulton brothers hired him to promote Garden City, especially to persuade the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad to install a switch station. The railroad agreed to place its station at Garden City. The town’s name was inspired by a garden planted by William Fulton’s wife, Luticia, in the summer of 1878.

Main Street ran north and south, dividing William D. and James R. Fulton’s claims. They erected two frame houses as soon as they could get building materials. William D. Fulton built a one-and-a-half-story house on his land on the east side of Main Street with two rooms on the ground floor and two rooms above. This was called the Occidental Hotel, with William D. Fulton as the proprietor. No other houses were built in Garden City until November 1878, when James R. Fulton and L.T. Walker each built a building. The Fultons tried to attract others to settle here, but only a few came, and by the end of the first year, there were only four buildings.

The original townsite of Garden City was platted on April 8, 1879, by the Garden City Town Company. The plat was filed at Dodge City, in Ford County, to which the then-unorganized Sequoyah County was attached. The land consisted of loose, sandy loam covered with sagebrush and soapweed, but no trees were present. However, by then, more people began to come to the area.

Town boosters took extraordinary measures to sell lots and attract new residents. In the Spring of 1879, former nurseryman Charles J. Jones shipped a carload of trees from Sterling, Kansas, and planted them along his lots on Jones Avenue to attract buyers. Before this, William Fulton’s Occidental Hotel boasted the town’s only tree.

The first issue of the Garden City Newspaper appeared on April 3, 1879. Three months after the paper’s establishment, the editor stated, “There are now forty buildings in town.” In the same year, the first telegraph lines were established throughout the city.

Following a sustained drought, irrigation arrived in Finney County in 1879 with the completion of the Garden City Ditch. Charles Jones was the first man to put it into practice in Kansas. He was the principal organizer of the irrigation companies that were soon to be in operation and of the canals in the unorganized counties south of southwestern Kansas. About 100 acres were irrigated in 1879, 500 in 1881, and 1,000 in 1882.

The Garden City Ditch, initially eight feet wide and two feet deep, grew to about 12 miles. When completed, the Kansas Irrigating Company’s charter covered over 30 miles, and its ditch irrigated 20,000 acres. The Minnehaha Irrigation Company, chartered July 6, 1880, had a ditch ready for use ten miles long, 20 feet wide, and three feet deep. This ditch was located on the south side of the Arkansas River, commencing at a point about six and a half miles west of Lakin in Kearny County. It was expected to irrigate a 16-mile-long, 2- to 3-mile-wide tract encompassing nearly 20,000 acres. The Great Eastern Irrigating Company soon also commenced operations.

The Garden City Irrigator, managed by W.E. Carr, was first issued on July 1, 1882. It was enthusiastically devoted to the city’s and county’s local interests.

Garden City was incorporated as a third-class city on January 13, 1883. George T. Inge, an ambitious young merchant, came to Garden City in the spring of 1883 to establish the Inge Brothers store. This was his first independent business, and he continued to sell goods in Garden City for the next 24 years. At about the same time, the Kansas Lumber Company established a lumber yard. It was the first lumber company in Western Kansas to build iron sheds and probably sold more lumber than any other single yard, with sales often totaling $20,000 per month.

At that time, Garden City had a population of nearly 400. It boasted two hotels, two grocery stores, a general store, two carpenters, a lumber dealer, a blacksmith, a meat market, two physicians, three attorneys, a Congregational Church, a Methodist Episcopal organization, a Cumberland Presbyterian Society, and a subscription school of some 30 students. By this time, wood-frame false-front commercial buildings predominated the city. However, many of these early wood-frame buildings burned in a devastating fire in 1883.

Finney County was organized in 1884. The first meeting of the board of commissioners of Finney County was held in the Metropolitan Hotel on October 2, 1884, in Garden City. The first school district in the county was formed on November 24, 1884. At that time, Garden City had 1,569 residents, and 2,905 acres were under cultivation, in addition to those used for cattle ranching.

Meetings continued in the Metropolitan Hotel until January 1, 1885, when a small frame building was rented for courthouse purposes. It was located in block 37 on the east side of Main Street. The county officers furnished their rooms but were allowed $5.00 per month for rent, fuel, and lighting. The Dickerson Theatre was then built on the site of the first courthouse.

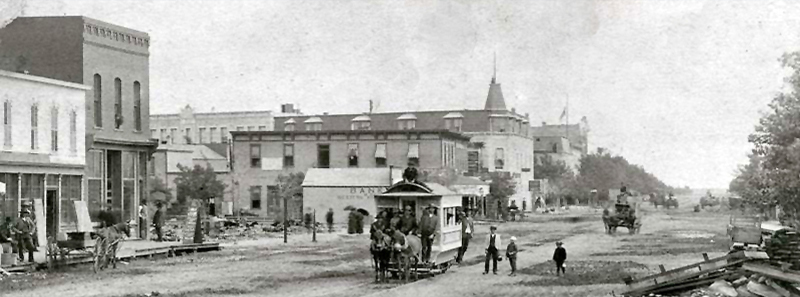

Vintage Garden City, Kansas.

Although Garden City was the likely county seat, Charles J. Jones took no chances, and at a meeting of the board of commissioners on August 3, 1885, Charles J. Jones made an offer to build a courthouse, which was accepted. Work began on the new courthouse at once. Jones hosted cornerstone ceremonies at the courthouse and his future Buffalo Hotel on the same day. That day, Jones also auctioned off $31,000 in lots in Garden City and Hartford. The city easily won its bid for county seat over Sherlock (Holcomb) and Pierceville.

In the vicinity of the courthouse, lots sold for $175 to $200, totaling $24,000. The sale continued until four o’clock, when Mr. Jones invited everyone to board his two coaches at the depot for a free ride to Hartland and back. The coaches were filled, and the sales there totaled $7,000, bringing the day’s total to $31,000. The proceeds from the sale of this lot were used to build the new stone courthouse.

When the courthouse was completed, it had four rooms below, two office rooms, and a large courtroom upstairs. The total cost of the building was about $6,000. Two iron cells were ordered and placed in the county jail in an upper room in the courthouse on February 25, 1886, for $3,464. These were the first in the county. The Jones courthouse was used until February 1902. Most of the time, it was necessary to use a courtroom outside the building because the room was too small.

Jones opened his Marble Block, a two-and-a-half-story commercial block adjacent to the Buffalo Hotel, in early October 1885. Architects J.H. Stevens and C.L. Thompson of Topeka, Kansas, designed the buildings. Both buildings were constructed from quarried limestone from Kendall, Kansas, cut into large blocks and transported to Garden City by flatcars.

The Buffalo Hotel, at 111-117 Grant Avenue, was completed and opened on October 12, 1885, just one month after Jones set the cornerstone. The front exterior of the Italianate-style hotel featured beautifully carved stone columns, iron pillars, and large plate glass. The first floor housed a stairway, the lobby office, dining room, billiard hall, sample room, kitchen, and laundry. There were 80 guest rooms on the second and third floors. The building was connected via an opening off the second-floor hallway to the adjacent Marble Block, which housed guest rooms and offices. The interior was filled with the latest technological gadgets and stylish furnishings. Innovations included a “system of electric call bells,” an electric fire alarm, a laundry, and a wind-powered water tank for fire suppression and water closets. The construction of the hotel cost $40,000, plus an additional $10,000 for Queen Anne furniture and Brussels carpets.

Jones hired Ben Phillips to manage the hotel, which he had owned and managed for 14 years. The two easternmost storefronts housed a drug store and a clothing store.

The hotel was part of Jones’ effort to focus the community’s commercial activity along his Grant Avenue. The hotel provided housing for transients, served as a meeting place for locals, and attracted newcomers and tourists. It also served as an office for the Cannon Ball Stage Line. In its early years, the ground-floor shops featured drugs and clothing in 1887, implements in 1892, and hardware, grocery, and tinware in 1899. By 1905, storefront shops included grocery stores, feed stores, and hardware stores. City Directory listings included Cafe and Billiards in the 1940s, Schulman Hardware, and Row’s G.E. Service in the 1950s. The building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, still stands in Garden City.

Garden City’s county-seat designation coincided with a statewide real estate boom. Between 1885 and 1887, a rush to Western Kansas brought settlers in significant numbers. The United States Land Office was established in Garden City. I.R. Holmes, the agent for the sale of lands of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, and Holmes’ partner, A.C. McKeever, in 1885, sold thousands of acres of railroad and private land. At the height of the boom, in late 1885, the Garden City Irrigator touted the city’s achievements:

“There is no longer room for any town West of Wichita to dispute Garden City’s claims to the metropolis of the great West, which are pushing along at such rapid strides that there is no possibility of any town ever coming within hailing distance of us. Our future is made. We have the finest country in the land, and we are reaping the benefits of it. Our citizens are not selling lots and sticking the money in their pockets. They are putting the money into valuable improvements, showing the world that those best positioned in this region are not afraid to make investments.”

The streets of Garden City were soon crowded with horses, wagons, buggies, and teams of oxen. Long lines of people stood out in the weather awaiting mail at the post office, and there was always a crowd in front of the land office. During the boom, the town had nine lumberyards, 13 drugstores, and two daily newspapers. Nearly everyone used kerosene lamps, and a few were placed on posts on Main Street. There were no city waterworks, so everything depended on shallow wells, which were strongly alkaline. Passenger trains of two or three sections arrived daily, carrying passengers, most of whom disembarked at Garden City.

The streets of Garden City were unpaved for many years, but in the spring of 1886, they were graded for the first time. The city also began using horse-drawn water wagons as street sprinklers to reduce the dust.

Soon after the Buffalo Block was completed, John A. Stevens built the Grant Block, thereby isolating Jones’ buildings from the growing number of permanent structures on Main Street. Stevens appeared to have outmaneuvered Jones by constructing the Opera House and Windsor Hotel on North Main.

In 1887-88, John A. Stevens built the Windsor Hotel at 421 North Main Street. J.H. Stevens and C.L. Thompson designed it in the Renaissance style.

The four-story building, which has a basement, measures approximately 120 feet long, 100 feet wide, and 55 feet high. The exterior walls were built of native limestone and red bricks fired in a local kiln. The hotel’s most distinctive feature is the square tower over the main entrance at the northeast corner, which rises to an additional story.

The principal feature of the interior is the mezzanine lobby, which rises three stories and is topped by a full-length skylight. The lobby walls are lined with balconies on three sides, and on the fourth side, two long, solid mahogany stairways converge at the bottom. Rooms on each floor are arranged in two rows along the exterior of the building; those on the interior open onto the central court formed by the mezzanine lobby. The Windsor Hotel cost approximately $100,000.

A business rivalry between John Stevens and C.J. “Buffalo” Jones, who had just completed the Buffalo Hotel and the Marble business block, provided the incentive to construct the 125-room hotel. The Windsor Hotel was known as the “Waldorf of the Prairies” for its lavish accommodations. Early guests included Eddie Foy, Lillian Russell, Jay Gould, and Buffalo Bill Cody, who stayed in the presidential suite on the third floor.

In the meantime, Jones’ vision for the Buffalo Hotel was cut short. When the Windsor Hotel opened, the Buffalo Hotel was converted to a rooming house.

In addition to providing lodging and meals for travelers, the hotel hosted banquets, balls, and social gatherings and served as the headquarters for local cattlemen. Guests could enter Steven’s Opera House, which adjoined the hotel to the south, through an entrance at the Windsor Court. It was reportedly the most prominent hotel between Denver, Colorado, and Kansas City, Missouri, from the late 1880s to 1900. The Windsor was noted for its fine dining room, a reputation that lasted until the mid-1920s when meals were no longer served. The building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, still stands in Garden City.

However, an impending crisis was imminent. The first sign of what was to come came in the form of the Blizzard of 1886, in which an estimated 75% of cattle in ranching counties were lost, and, consequently, many ranches went bankrupt. Railroad over-expansion, the ever-present drought, and foreclosures on mortgaged farm and ranch properties.

During these years, many people fled western Kansas. Between 1887 and 1891, the population of Finney County plummeted from an estimated 10,000 to 5294.

When hard times made it impossible for the heavily indebted Jones and Stevens to pay their mortgages, the Windsor and Buffalo Hotels were foreclosed upon in 1890.

Over time, as Garden City’s economy rebounded, the Buffalo Hotel was reoccupied. In 1892, the two westernmost storefronts housed a restraint and printing office; the southern two storefronts housed an implements business.

As in many Kansas communities, the 1893 Cherokee Strip Run further exacerbated the population decline. Subsequently, its progress was more conservative, and the improvements were more substantial than in earlier years.

Silas Schulman moved his plumbing and hardware business into the old Buffalo Hotel building in 1895. In 1897, the hotel became home to the city’s first library. By 1899, although the second floor continued to serve as a rooming house, the third floor was vacant. The first floor of the old Buffalo Hotel housed a grocery and tin works, as well as Schulman’s hardware store.

In 1900, the first U.S. census was taken, the city was incorporated, and its population was 1,590.

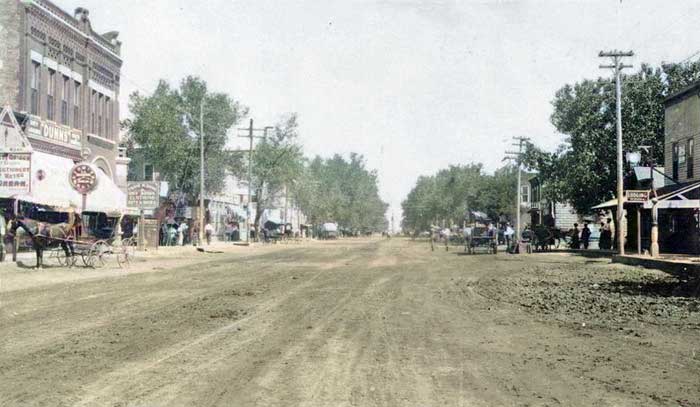

Garden City, Kansas, Main Street, early 1900s.

The city languished until the first decade of the 20th century,y when the population partially rebounded to nearly 4,000. The comeback was partly tied to the region’s production and processing of sugar beets. In 1901, the Kansas Legislature began subsidizing sugar beet production.

By 1905, Schulman had expanded into the eastern two storefronts of the old Buffalo Hotel.

When the first telephone line was built, trees grew on both sides of Main Street. Although these interfered with the wires, residents knew that the value of trees in Western Kansas would not permit them to be cut, and the telephone poles were set along the center of the street.

In 1907, investors built an 800-ton sugar beet factory for $1 million, processing the crops produced by federally subsidized farmers. By 1912, the factory turned out 200,000 pounds of refined sugar daily. Sugar Beet production remained a key industry through World War II. It declined after government subsidies ended in 1957. The sugar beet industry brought migrant farm workers and Mexican immigrants to the area.

Another project that began in 1907 was the Garden City Experiment Station, which used its 320-acre site, located northeast of town, to investigate dryland agriculture. It continued successfully into the 1990s.

“No city of its size in the West can boast finer business blocks of stone and brick or more comfortable and beautiful homes than Garden City. There were no empty houses or business places; the people mostly owned their own homes and took pride in keeping them in perfect repair. Property to rent was scarce, and demand for more houses remained constant.

— The Garden City Herald, February 16, 1907.

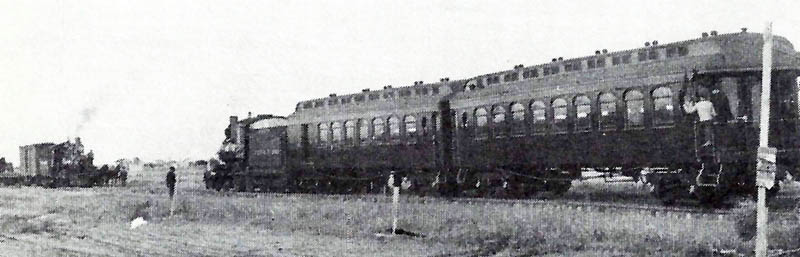

Garden City, Gulf, and Northern Railroad, 1909

In 1908, the Garden City, Gulf, and Northern Railway was completed.

In 1910, Garden City was located on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad and the Garden City, Gulf and Northern Railroad. It was the commercial center of a large and prosperous irrigated district in the Kansas beet sugar region. It had electricity for lighting and power, waterworks, a sewer system, fire and police departments, a county high school, a public library, a hospital, an opera house, three banks, and three newspapers — the Telegram, a daily, and the Imprint and Herald, weeklies. There were two seed houses, which cured and marketed native seeds. Several firms manufactured stock tanks, pumps, and various well supplies. There were also two grain elevators, a flour mill, and a planing mill. That year, GardenCity built its first high school, Sabine Hall. At that time, the city reported a total population of 3,171, an increase of almost 100% in the last decade.

Daily stagecoaches ran to Santa Fe, Eminence, and Essex, and tri-weekly stages ran to Terryton. The shady streets and fine lawns in the residential portion of Garden City indicated that the city was well-named. The business district covered several squares and was built of brick and stone. The city was equipped with telegraph and express offices, telephone accommodations, an international money order post office, and two rural routes.

The National Old Trails Road, also known as the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, was established in 1912 and ran through Garden City. That year, the city fathers decided to oil Main Street. The September 20, 1912, edition of the Garden City Telegram reported, “Main Street is being oiled at last. The start was made on South Main Street below the tracks, where the loose soft dirt has, on every windy day, poured up Main Street in choking blasts. Oiling will continue up Main Street as far as the oil lasts.”

By 1913, the Garden City Telephone, Light, and Manufacturing Company, formed in 1907, had 40 miles of long-distance line connecting Garden City with Lakin, Pierceville, Holcomb, and Deerfield.

In 1916, the Garden City Western Railway, which extended 20 miles northwest through the sugar beet company’s fields, was built to haul beets to the factory but soon began hauling wheat and other products to connect with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad.

Garden City Western Railway

In 1917, Garden City built Calkins Hall, which was used as both a Senior High School and a junior college.

The first long-distance telephone service from Garden City was a nine-mile line, built in 1919.

The Garden City Co-op Inc. was organized in 1919, beginning with a single elevator along the railroad tracks. The railroads provided easy access to the larger markets.

It was soon after the end of World War I that Garden City decided it had been fogging up downtown long enough. By August 1919, plans were to pave Main Street with brick. Work started at Maple Street, two blocks south of the Santa Fe Railroad crossing, and extended north to Kansas Avenue, a distance of about one mile. Other streets then were bricked, including Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Grant, Laurel, Chestnut, Pine, Garden City Avenue, and all other short streets between 7th and 9th.

A grocery and express office occupied the western two storefronts of the old Buffalo Hotel in 1920. In 1922, Frank M. Dunn, John F. Walters, Raimon G. Walters, and Silas Schulman’s son Sibel purchased the Buffalo Block from Charles E. Gibson. It was the first time the block had been locally owned since Jones lost it to creditors three decades earlier. By 1929, the building housed a tire and service store and an express office. The first floor served as the base of operations for his irrigation business. The second and third floors were offices, apartments, and sleeping rooms.

F.A. Myers bought the west half of the hotel in 1925 for his Garden City Creamery. The business was passed down to Myers’ son, Merle, and grandson, Carl. Until 1943, there was a soda fountain there.

A movement for a new courthouse began in 1928. Members of the American Legion circulated petitions, and the names of 51% of the voters were secured in favor of a new building. An on-site election was held, and a large majority voted to return to Jones Park. The cost of the four-story building was about $186,323.21. Made of steel and solid cement construction, faced with Bedford, Indiana, stone, the building is 76 feet by 107 feet. The building stands on the site of the original courthouse in the C.J. “Buffalo” Jones Park.

In part because of an influx of immigrant workers, Garden City’s population had nearly doubled again to 7,116 by 1930. However, it did not return to its 1887 population level after World War II. After the war, Garden City became a livestock center, with feedlots and packing plants emerging in the 1960s.

By this time, the luster of community hotels had begun to fade. Independent restaurants fed the town’s residents. Apartment buildings, common after World War I, housed temporary residents and unmarried people. Movie theaters entertained broad audiences. Roadside motels, situated along highways, which had begun to take precedence over the railroads, catered to travelers. As a result, many small-town hotels lost their appeal.

In 1964, Main Street underwent a major improvement project. Then, Main Street was resurfaced with asphalt from the railroad tracks to Kansas Avenue.

In the 1970s, Garden City’s city council allowed the construction of a meatpacking plant, which invigorated the economy. Many new arrivals were immigrants from outside the United States, from Myanmar, Somalia, Vietnam, and other places, particularly Mexico and Latin America.

After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, immigrants from Southeast Asia began coming to Garden City with the help of Garden City Catholics, who sponsored an initial group of Vietnamese immigrants that year.

In 1977, the Windsor Hotel closed. The hotel is four stories tall, or about 50 feet. Initially, the hotel had 125 guest rooms; following remodeling and modernization, it now has 85. A portion of the first floor now houses commercial enterprises, and the fronts of these businesses have been altered with aluminum-framed doors and windows, painted brick, and metal. From the second floor upward, the building’s exterior retains its original appearance. The Finney County Preservation Alliance owns it.

In the 1980s, more Hispanics and Latinos, including immigrants, began working in meatpacking plants. At that time, many educational institutions for adults were teaching Hispanic immigrants after they had asked for amnesty for having illegally immigrated. More Vietnamese and Lao people also came. By the late 1980s, many Mexican immigrants had replaced Vietnamese immigrants who had left Garden City, as the Vietnamese had accumulated sufficient capital to seek employment elsewhere.

By 2010, over 48% of the population was Hispanic, and less than 40% was non-Hispanic white.

The 2020 census found that 53.1% of the city’s population was Hispanic.

Today, Garden City’s economy is primarily driven by agriculture. Several feedlots and grain elevators are located in and around the city. Additionally, an ethanol plant, Bonanza Bioenergy, was built in 2007 by Conestoga Energy Partners, which uses 19.6 million bushels of grain.

The community is served by Garden City’s USD 457 public school district. Garden City Community College is fully accredited.

Finney County Transit operates City Link, a public bus service with four routes in the city, as well as a minibus paratransit service. BeeLine Express, a Greyhound Lines subcontractor, provides daily eastbound bus service to Wichita.

Garden City Regional Airport is located approximately eight miles southeast of the city. It is used primarily for general aviation and is connected to the American Airlines network via American Eagle regional service to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport under the Essential Air Service program.

Three rail lines serve Garden City: the La Junta Subdivision of the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway and the two lines of the Garden City Western Railway, of which the city is the southern and eastern terminus. Amtrak uses the La Junta Subdivision to provide passenger rail service; Garden City is a stop on the Southwest Chief line.

St. Catherine Hospital serves Garden City. The Southwest Kansas Surgery Center, Heart Center, Cancer Center, and Maternal-Child Center provide additional employment opportunities, as do several other health-related businesses.

Initially named by its developers “The Big Dipper,” Garden City’s “The Big Pool” is larger than a 100-yard football field, holds 2.2 million gallons of water, and is large enough to accommodate water skiing. Originally hand-dug in 1922, the Works Progress Administration added a bathhouse during the Great Depression. Later, local farmers used horse-drawn soil scrapers to enlarge the pool. The pool features 50-meter Olympic lanes, three water slides, and a children’s pool with a zero-entry depth. The pool employs at least 14 lifeguards, two slide assistants, three admission clerks, two concession workers, and a pool manager on duty each day. Advertised for years as “The World’s Largest, Free, Outdoor, Municipal, Concrete Swimming Pool,” the pool has been known to count up to 2,000 patrons during the summer months. An admission fee is now charged to finance improvements made in recent years. In 2020, the Big Pool was renovated and rebranded as Garden City Rapids. Several giant water slides and a lazy river were added.

Located inside 110-acre Finnup Park, the pool is co-located with the Finney County Historical Museum and the Lee Richardson Zoo, the largest zoological facility in western Kansas, which houses more than 300 animals representing 110 species. Walking tours are free to the public; there is a fee to drive into the zoo.

A few miles from Finnup Park, the Big Pool, and the Lee Richardson Zoo is the Buffalo Game Preserve, home to one of the largest herds of bison in the world.

Garden City is located in southwestern Kansas at the intersection of U.S. Route 50 and U.S. Route 83. It is 192 miles west-northwest of Wichita, 204 miles north-northeast of Amarillo, Texas, and 255 miles southeast of Denver, Colorado. The city has a total area of 8.82 square miles. It is the most remote city in the United States, with a population of over 25,000.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2025.

Also See:

Clutter Family Murders – In Cold Blood

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Blanchard, Leola Howard; The Conquest of Southwest Kansas, Wichita Eagle Press, 1931.

Cutler, William G.; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Finney County, Kansas

Historic Marker Database

National Register Nomination – Buffalo Hotel

National Register Nomination – Windsor Hotel

Wikipedia

Silk Stocking Row Historic District