St. Paul, Kansas, is a small town in Neosho County. As of the 2020 census, the city’s population was 614, and its total area was 1.22 square miles, all of it land.

Father John Schoenmakers founded Osage Mission on April 28, 1847, seven years before Kansas became a territory and 14 years before statehood. Called the “Apostle to the Osage” and the “Father of civilization in Southeast Kansas,” he served 36 years as a spiritual director, doctor, steward, lawyer, judge, catechist, and preacher to the Osage Indians.

Father Schoenmakers arrived with Father John Schoenmakers, Father John Bax, and three lay brothers: Thomas Coghlan, John De Bruyn, and John Sheehan. They immediately established the male department of Osage Manual Labor School. On October 10, 1847, four Sisters of Loretto arrived, and the female department was established. The missionaries, both men and women, and many who followed were recent European immigrants. Most of them would spend the rest of their lives at the Mission.

Another leading man in the Osage Mission was Kentucky-born John Allan Mathews. He was married to Mary Williams and, after her death, to her sister Sarah Williams. The Williams sisters were the daughters of William S. Williams and his Osage wife, A-Ci’n-Ga. They first met Mathews while attending school in Kentucky following their mother’s death. Mathews was a slaveholder and southern sympathizer. He married Mary in Jackson County, Missouri, in 1835 and was appointed blacksmith for the Seneca tribe in 1837 and the Osage in 1839.

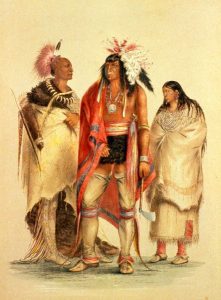

The origins of the Osage Catholic Mission are traced to Osage and Jesuit activity during the early 1820s. The Osage, a proud, industrious, and perceptive nation, accepted that white civilization would come and realized their young people must be prepared to adapt. In 1820, the Chiefs of the Great Osage and Little Osage tribes sent a delegation to St. Louis, Missouri, to meet with Bishop DuBourg. They requested that mission schools be established in Osage territory west of the Missouri frontier and north of what would later become the Oklahoma Indian Territory. The Bishop of New Orleans was receptive to their request since he was considering the placement of one or more central missions in that territory. From these stations, missionaries could establish schools for Indigenous peoples and settlers, establish mission stations where settlers could gather to hear Mass and receive the sacraments, and eventually build chapels and churches. The plan was launched, but it would take additional trips to St. Louis, Missouri, and Washington, D.C., to gather government support and funding for the missions.

In the early 1840s, the Jesuits identified several missionaries and established a mission seminary to train priests. Several young Osage men were recruited to provide language and customs training for future mission leaders. The decision was made to locate a mission on a small hill near the convergence of Flat Rock Creek and the Neosho River, about 30 miles west of the frontier border and 40 miles north of the Indian Territory.

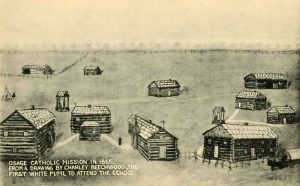

In 1845, a contract was awarded to construct the first Mission buildings. Father John Schoenmakers visited the site the following year to meet and become familiar with the Osage people.

The Mission team, led by Father Schoenmakers, established and sustained a robust, long-standing mission presence in an area where several previous attempts had failed. Success is attributed to the skills and interrelationships within this extraordinary group, as well as Schoenmakers’ insight.

While previous missionaries had tried to civilize the Indians by stripping them of their culture, Schoenmakers allowed a blend of native customs integrated with Christianity. He also knew that, to be successful, he must educate the Osage girls as well as the boys. The ensuing Osage girls’ school eventually became one of the region’s most successful.

The Osage Catholic Mission was the most important and influential frontier settlement in Southeast Kansas. After its establishment, it rapidly became a gateway for commerce and exploration in the frontier territory. The influence of a handful of Jesuit Missionaries spread Christianity and elements of the missionaries’ diverse cultures across more than 150 mission stations in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The Mission also provided the Osage Indian Nation with an educational and financial foundation, allowing it to become one of today’s most affluent tribes.

When a post office was established on March 20, 1956, it was called Catholic Mission, with Father Schoenmakers as the postmaster.

In 1861, John Allan Mathews gathered a group of Osage who attempted to force Schoenmakers to leave the area because they opposed Schoenmakers’ abolitionist ideas. The 6th Kansas Cavalry, under General James G. Blunt, killed Matthews in fighting at Chetopa, Kansas, on September 18, 1861.

Union and Confederate troops were interested in the Osage Mission during the Civil War. From about December 1862 to June 1865, Union soldiers intermittently stationed at or near the Mission. At least a couple of times, Confederate supporters entered the Osage Mission or were in the immediate vicinity.

In 1866, before the town was founded, two buildings were erected, one by L.P. Foster & Co., a log cabin in which a store was kept by the “Morgan boys,” and a frame structure built by S.A. Williams of Fort Scott, in which his son kept a store. S.J. Gilmore opened another small store in a log building called “Castle Thunder” in 1865.

The first lawyer in town was C.F. Huchings in 1867; the first doctor was A.F. Neeley. The town’s early growth was rapid. That year, Anson Gridley taught the first school. Within eight months, the town had over 20 stores and 900 residents. It was the center of three stagecoach lines: one to Fort Scott, one to Humboldt, and one to Chetopa. This point was a strong rival of Erie’s for the county seat for several years.

In December 1867, a town company was formed, composed of George A. Crawford, S.A. Williams, C.W. Blair, Benjamin McDonald, and John Nandier, and a town called Osage Mission was platted. Another town, “Catholic Mission,” was located adjacent to it on the west. At that time, A.D. Williams moved his stock of goods, which he kept at the post office. About the same time, L.P. Foster & Co. erected a two-story frame building across the street, Joseph Roycroft built a log saloon, Middaugh and Dohnan came down from Topeka, Kansas, and built a store, and James Roycroft erected a boarding house. Soon, the Catholic Mission site was absorbed by the Osage Mission.

The first town school was established in the winter of 1867-68. It was a subscription school taught by Anson Gridley, a senior, and kept in a small frame building on the southwest corner of County and Oak Streets.

In 1868, Father John Schoenmakers deeded a block of the land he acquired from the Osage Indians to a new Osage Mission Town Company.

That year, Marston & Ulmer, from Iowa, opened a furniture store, J.M. Boyle, from Fort Scott, opened a hardware store, and Ryan & Roycroft started a general store. Mary Anna Swank taught in a tented building in a public school in the summer of 1868.

The Neosho County Journal was established on August 5, 1868, as a five-column folio by John H. Scott. On June 17, 1869, it was enlarged to six columns, and on July 28, 1870, to eight columns. The Journal was generally Republican in politics.

The Methodist Episcopal Church was organized on August 15, 1868. Services were held in the schoolhouse until a one-story frame church with a steeple and belfry was built. A Sunday school was organized on November 8, 1869.

On October 12, 1868, the post office name was changed from Catholic Mission to Osage Mission.

The Baptist Church was organized on November 13, 1868, by Reverend A. Hitchcock, and its initial services were held in the school building. Steps were taken to build a church in the latter part of 1868. The building was erected in the following summer but was not completed. To facilitate its erection, the Town Company donated the lots on which it is located and made a two-year, interest-free $1,000 loan to the society. The Sunday school was organized on September 25, 1869.

By the end of the year, the town contained eight dry goods stores, three drug stores, a hardware store, two boot-and-shoe stores, four blacksmith shops, numerous other business establishments, and a population of nearly 900. Many settlers had relocated from Kentucky, Pennsylvania, New York, and other eastern locations. Many were immigrants. Among the settlers were Civil War Union veterans who took advantage of the Homestead Act’s benefits.

The town’s growth was steady from this time until the building of the railroad. It was the center of three lines of stages: one to Fort Scott, one to Humboldt, and the other to Chetopa.

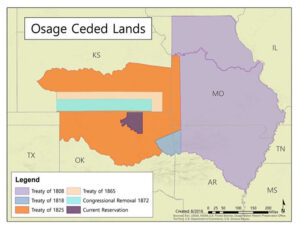

In January 1869, public school quarters were taken up in a building rented by N. Tucker.

That year, after an intense political struggle with the Leavenworth, Lawrence & Galveston Railroad, the Osage ceded their Kansas lands to the government for $1.25 an acre. They then moved to a reservation in northern Oklahoma. The departure of the Osage was painful for the tribe and the Mission. However, this transaction left the tribe with $8,536,000 in the U.S. Treasury, paying interest to all tribe members. Rich Bluestem grass provided grazing for wildlife and stock, and oil, deep beneath the ground, added to the Osage’s wealth. Today, the Osage Nation is among the most affluent and influential Native American tribes.

After they left, Father John Schoenmakers received more than a section of land from the Osage as part of the treaty agreements. He then gathered a group of Fort Scott businessmen, gave them a section of land, and started the Osage Mission Town Company.

Father Schoenmakers also realigned his strategy to focus the school’s instruction on white students. The resulting St. Ann’s Academy and St. Francis Institute campus covered a large area, attracting students from many states and Mexico. The school encouraged settlement, and the population grew to approximately 1,600.

In addition to parish schools, the Jesuits and the Sisters of Loretto built two boarding colleges: St. Francis Institute for men and St. Ann’s Academy for women. After establishing the education system, Father Schoenmakers stepped back from his town company and focused on ministering to the needs of the newly arrived settlers and on school management. While the boarding schools had a relatively short life, the education system started by the Jesuits in 1847 endured.

On April 10, 1869, the trustees of the Osage Mission Town Company held their first meeting to begin the incorporation process. The town was then organized as a third-class city, with John O’Grady as mayor. By then, much of the town was platted and ready for the flow of settlers cascading across the Missouri border. Osage Mission was well positioned, only 29 miles west of that border, and it already had a school and a church. To add appeal, Father John’s town company quickly acquired a Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway connection and a new, state-of-the-art steam-powered flour mill. The mill’s opening was vital because it provided the new town and the surrounding farmers with a substantial economic boost. The town grew rapidly, and much of the money from real estate sales was directed to schools.

The Mission Mills, located on Flat Rock Creek, about a mile east of Osage Mission, was built by Ryan & Roycroft in 1869 for $22,000, including machinery and power. The building was a two-and-a-half-story frame above a stone basement. The machinery consisted of four runs of buhrs, with a capacity of 100 barrels of flour per day, and was propelled by a 50-horsepower engine. An elevator was in the upper part of the building, storing 20,000 bushels of wheat. The market for these mill products was local demand, and they were also sold in the Indian Territory and Texas. The Mission Mills were sold in 1875 to the First National Bank of Parsons, Kansas, then resold in 1877 to Hutchings & Barnes.

Grist Mill in St. Paul, Kansas.

By 1870, the missionaries had “shifted gears.” The Osage were gone, scores of settlers flooded onto the new Kansas frontier, and the mission was at the doorstep of the westward expansion. The Mission was in an interesting position for another reason. Entrepreneurs seeking to establish new settlements recognized the need for funding for essential schools and churches. Schools and churches already existed at the Mission site and in the early stages of commerce.

During this period, Father Schoenmakers also decided that the existing log Saint Francis de Hieronymo Catholic Church would be inadequate for the growing population. In 1871, work was started on the existing stone church.

The first bank, the Neosho County Savings Bank, was established in the same year by Pierce & Mitchell. It was subsequently organized under State law as the Neosho County Saving Bank, with an authorized capital of $100,000. In August 1876, J. B. Pierce sold his interest to E.W. Bradbury, and the firm became Mitchell & Bradbury. The firm failed in February 1879. At this time, J.B. Pierce established the City Bank. It is a private institution engaged in general banking, lending, and collection. It is also a bank of deposits.

Saint Peter’s Episcopal Church was organized on December 12, 1870. A Sunday school was organized on January 1, 1871, and a small frame church building was erected in 1874.

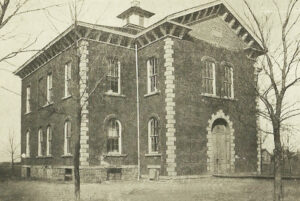

A sizeable two-story brick school building was erected in 1872. It had 277 students and four departments: high school, grammar school, intermediate, and primary.

The Osage Mission Stone Mill was built in 1875 by A.W. Althouse. It was a small stone structure, 30 feet long by 20 feet wide, and 1.5 stories high. It contained three runs of stone and could grind 70 bushels of wheat and 100 bushels of corn per day, powered by a 20-horsepower engine.

F.W. Ward started the first newspaper, The Neosho County Republican, in September 1880 by F.W. Ward as the Neosho Valley Enterprise. At first, it was a four-column quarto. Shortly after its inception, D.C. Ambrose purchased a half-interest, and in September 1881, the paper was enlarged to an eight-column folio. The Enterprise was conducted as a Democratic paper until October 19, 1882, when T. F. Ross purchased one-half interest. At that time, the name was changed to the Neosho County Republican, and the politics shifted to align with it.

In 1880, the town’s population peaked at 1,306.

C.C. Nelson started the Neosho County Bank in March 1881 with S.F. Denison as the cashier. This concern lasted only 40 days, after which Nelson abandoned the business and took up residence as a British subject in the Dominion of Canada.

The Christian Church was organized in May 1881. In the fall and winter of 1882, a small frame church was built for $800.

The Neosho County Democrat was established on January 3, 1883, by A. Conn as an eight-column folio. It was Democratic in politics.

Funding constraints delayed the church’s completion because Father Schoenmakers did not want to impose a heavy debt on the settlers. Unfortunately, as the church was nearing completion, Father Schoenmakers, in the 50th year of his priesthood, died on July 28, 1883, and was buried in St. Francis Cemetery, one-quarter mile east of the Church.

Finally, after 13 years, the church was dedicated on May 11, 1884.

Early day Saint Francis de Hieronymo Catholic Church.

When W.W. Graves entered St. Francis Institute in the fall of 1889, the school’s days were numbered. The Jesuits faced the same issues that many contemporary school administrators face—funding, resources, and consolidation. There were two Jesuit boys’ schools in Kansas, one in Osage Mission and St. Mary’s School northeast of Osage Mission. Jesuit scholastics were stretched thin. St. Francis Institution owed $27,000, and recurring droughts reduced the value of the 1,500-acre farm. In 1891, the decision was made to discontinue operations at St. Francis Institute. After the Jesuit departure, St. Francis Catholic Church was served by two secular priests under the guidance of Bishop Fink of Leavenworth.

In April 1893, a Passionist priest, Reverend Raymond O’Keefe C.P., traveled from St. Louis, Missouri, to St. Paul to give a retreat. At that time, the Passionist Order was seeking a location farther west. Father O’Keefe was impressed by the location, the local congregation’s apparent devotion, and the Osage Mission’s historical holiness. On his return to St. Louis, he began a correspondence with his superiors regarding his order. His enthusiasm was rewarded.

On November 23, 1893, the Osage Mission Journal reported, “Reverend John Baptiste C.P., provincial of the Passionist Fathers, visited Osage Mission officially regarding the movement to establish a Passionist Monastery here.”

When the Passionists took possession of the Jesuit property on April 1, 1894, they acquired the 34 acres of land on which the present church sits, the large stone monastery building that would be used as a retreat house, a third stone building that was used as a school, a three-story frame structure known as the College Hall, a stable, an ice house and a building that was used as servant’s quarters. They also acquired a severe structural issue that was dealt with later.

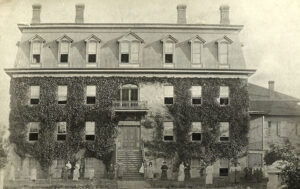

At that time, the existing three-story stone structure, a former Jesuit monastery completed in 1872, was razed to make room for the larger Passionist Monastery. The original Jesuit Infirmary/Guesthouse was lifted and relocated to a site about six blocks west of the church. The three-story College Hall structure was lifted and relocated east of the church. It served as a parish hall until 1960.

On May 11, 1895, the town’s name was changed from Osage Mission to St. Paul. It was a controversial name change, and the loss of the schools and staff hurt the local economy and population.

On June 26, 1895, the Academy’s Bijou Club strings group presented its final Osage Mission Concert.

After years of agitation to change the town’s name from Osage Mission, which suggested it was still an Indian Mission, the change was put to a vote of the residents. Neona was proposed to honor the daughter of Chief Little Bear, but local protests favored St. Paul. Residents voted on April 11, 1895, choosing the name St. Paul. On July 1, 1895, the name of Osage Mission was formally changed to St. Paul.

By the start of the fall semester of 1895, St. Ann’s Academy was flourishing. The school and its students had become a part of the community, and the community responded with support and affection. In the words of Sister Fitzgerald in Beacon on the Plains:

“The schools were something of a mecca in the people’s social life. Musicals, art exhibitions, and commencement exercises drew larger crowds than the halls could accommodate in the days when entertainment was an art and not a commercial enterprise.”

On September 3, 1895, a fire caused by a defective flue destroyed the St. Ann’s Academy Complex. It was a devastating blow to the Sisters of Loretto. With only $16,000 of fire insurance, they could not afford to rebuild the academy. Despite pleas from the citizens and the Passionists, the Lorettos left in August 1896. Afterward, the Ursuline Sisters served St. Paul for about two years.

In April 1903, probably the most destructive tornado passed through the west end of St. Paul, leaving a path strewn with wrecked buildings, trees, and debris. A heavy hail storm preceded it, with large hailstones falling thick and fast for several minutes, completely covering the ground like snow. Trees were stripped of foliage, and the young garden vegetables were pounded out of sight. Livestock that was not under shelter suffered much. The most significant damage was to the public school building. The entire roof and bell tower were blown off, and windows were blown in. Although the building had $3,000 in cyclone insurance, it was insufficient to cover the repair costs.

In 1909, the Passionists knew the church had a severe foundation problem affecting the upper structure. The Passionists had contracted with the Kansas City firm Grant Renne, and the entire 7,000-ton structure was lifted from its foundation; a new basement foundation was then installed. Most of the labor to lift the massive structure was performed by residents under the supervision of Grant Renne engineers. Upon completion, the church rose by four feet, creating space for a basement chapel.

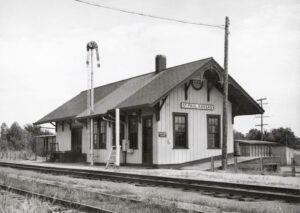

In 1910, St. Paul was the third-largest town in Neosho County. Located on the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway, it had two weekly newspapers, the Journal and the Anti-Horse Thief Association News, two banks, telegraph and express offices, an international money order post office with three rural routes, and a population of 927.

In 1911, the Passionists solidified their commitment in St. Paul when the Provincial Chapter decreed that a new retreat house would be built. This was a significant construction project requiring many changes to the existing church/school campus:

The new monastery retreat house was dedicated in November 1913. In 1914, it hosted four Passionist exiles from Toluca, Mexico, who had been driven from their monastery and arrived in St. Paul penniless and exhausted but thankful for their lives.

In 1936, the new monastery became more than a retreat house. In August, St. Paul became the location of the new Passionist Novitiate of the West. Classes of young men in heavy wool habits and sandals came and went annually. They were required to remain silent much of the time but were renowned for their monastery choir during Mass.

Passionist Monastery, St. Paul, Kansas.

A beautiful novice garden, now the church garden, was built and completed in 1940. The garden tower, which contains the bell from the original log church, was also completed in the late 1940s.

The St. Paul location was closed after being a Passionist novitiate for 30 years. The last novices left the St. Francis Retreat in 1966.

On February 23, 1983, the Passionists closed the St. Francis Monastery and Retreat House. After that, one Passionist remained the Parish priest for a few years. When Father Luke Connolly left in 1987 and transferred the parish and church property to a diocesan priest, it marked the end of more than 90 years of Passionist presence in St. Paul.

In 2009, a new high school and gymnasium were constructed on the site of the state’s oldest, continually operating school system.

Today, the St. Francis de Heironymo Catholic Parish is one of Kansas’s oldest continuously operating parishes. It stands majestically on Kansas Highway 47 at the east city limits. The beautiful Romanesque Revival building has five altars and is large enough to accommodate the entire population of St. Paul. The grounds are adorned with gardens, statues, a stone bell tower, and a walkway. There are three bells in the steeple that are rung every 30 minutes.

The Osage Mission-Neosho County Museum is directly south of the church. On the museum grounds, the Lone Elm School, a one-room schoolhouse from 1867 through 1951, stands.

A visit to the St. Francis Parish Cemetery reflects much of the Osage Mission’s history, as does the only remaining structure of the girls’ school, established by Mother Bridget Hayden upon her arrival at the Mission in 1847. The Osage Mission Infirmary & Guest House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is managed by St. Ann’s Bed and Breakfast. The owners strive to maintain their history and authentic design.

St. Paul’s annual homecoming is called Mission Days. It is held on Memorial Day Weekend and includes activities that begin on Thursday and conclude on Monday, including races, music shows, dances, pony and draft horse pulls, a parade, a horseshoe tournament, a carnival, kids’ games, a golf tournament, calf penning, and Memorial Day services at the local cemeteries.

St. Paul, Kansas, is located in the Neosho Valley, about six miles southeast of Erie, the county seat.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated January 2026..

Also See:

Historic Kansas Churches – Skyscrapers of the Plains

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

A Catholic Mission

Cutler, William G.; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Kansas Post Office History

Osage Mission Historical Museum

Sister M. Lilliana Owens, The Early Work of the Lorettines in Southeastern Kansas, 1947

St. Francis Catholic Church

St. Paul, Kansas

Wikipedia