Hoisington, Kansas, located in central Barton County, got its start in 1886.

Before that time, the pioneers of Homestead Township voted on bond issues to attract the Kansas and Colorado Railroad to the area. Some of the mainline grading was completed through this part of the state in 1885, but it was not until the fall of 1886 that the first work train arrived. The railroad was completed in the fall of 1886. The rail line was soon taken over by the Missouri Pacific Railroad. When a railroad station was built, it was called Monon, meaning “Lady of the Lake.” Lake Barton was constructed to provide water for the trains and shops, and the railroad station became a division point.

In the meantime, as the railroad was approaching, a group of Barton County businessmen formed the Central Kansas Town Company and began laying out a new town in 1886. That year, the first substantial building erected on the townsite was a two-story structure built by Brooker and Brown as a general merchandise store.

In 1887, many people from Iowa, Illinois, and other eastern states began to arrive, and the town grew steadily. Many of these residents took up farms on the productive ground of the area.

The post office, relocated from nearby Buena Vista, opened on April 14, 1887. The name was changed to Hoisington in honor of Andrew Jackson Hoisington, a prominent Great Bend businessman. Later, the railroad station would also change its name from Moran to Hoisington. That year, the city was incorporated, and the first election was held for city offices, with E.M. Carr serving as the first mayor.

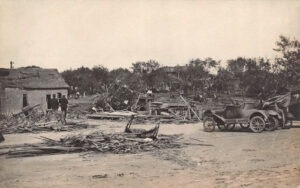

Early day Hoisington, Kansas.

One of the city’s early accomplishments was the construction of a Y.M.C.A., which was built between 1902 and 1903.

The money for the project was obtained through private subscriptions, donations from the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and Miss Helen Gould. Miss Gould also contributed special donations of books and musical instruments to the library.

The 60-foot-square building included a large dormitory room with 40 beds, which was rented to association members for 15 cents per night. It also included a reading room with newspapers, magazines, and periodicals, a bathroom with three tubs and five shower baths, a library filled with 2,000 volumes, and a correspondence room supplied with writing materials. The members used the large lobby to play chess, checkers, and other games.

The facility was dedicated on March 17, 1903, with a three-piece band consisting of a trombone, bass drum, and tuba leading a parade. Located at Main and Railroad Streets, the Y, with its library, player piano, and bathtubs with hot and cold water, was the city’s most popular spot for years.

J.E. Sponseller constructed Hoisington’s first light plant in 1903. Arc lights, which replaced oil-burning lamp posts, were first used.

The Peoples State Bank of Hoisington opened for business on June 15, 1903, in the backroom of T. C. Morrison’s Mercantile house. In a very short time, it moved to the J. B. McCauley Opera House Building, which they purchased in May 1904. The bank then enlarged the opera house, making it one of the finest banking rooms in Kansas. It was finished with marble on the outside and marble and mahogany on the inside. It featured modern conveniences such as electric lighting, hot-water heating, lavatories, and restrooms for its customers.

In 1904, the council called for a waterworks bond election. It passed, and the city built the first water system and standpipe.

By 1910, Hoisington was the second-largest town in Barton County. At that time, there were six general stores, three banks, three drug stores, a weekly newspaper called the Dispatch, mills and elevators, electric lights, good hotels, an automobile livery, which made daily trips to Great Bend and other towns, four churches, a public library, and good schools. The town was also supplied with telegraph and express offices and had an international money order post office with two rural routes. It had a population of 1,975.

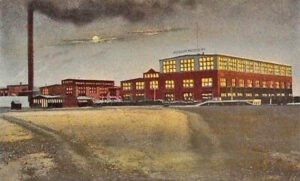

On September 28, 1910, work began on the first building that comprised many Missouri Pacific shops. This building was a roundhouse with fifteen 63-foot engine pits. The brick building housed a 75-foot-diameter turntable. The large blacksmith and machine buildings were equipped with the latest labor-saving machinery. Other buildings included offices, and when the shops were working at full capacity, a force of 1,600 men was required. The total cost of the plant was about $1,000,000.

When complete, the freight and passenger division on the Missouri Pacific Railroad operated the largest shops between Sedalia, Missouri, and Pueblo, Colorado. Next to Sedalia, the shops were the largest owned by this company in its entire system.

These operations brought more people to the area, many of whom were African American. At that time, black folks lived in South Hoisington, about a mile south of the city. Some were already settled there and were part of the Exodusters who came to Kansas after the Civil War. Others came to work when the railroad was initially built. However, they were not allowed to live in the city. Though the “town” was never platted, it became a melting pot of residents, including African Americans, Hispanics, and a few whites. Most lived in old wooden boxcars without running water, sewer, or electricity.

The Lind Hospital and Training School was established in Hoisington by Reverend W. J. Lind and opened to the public in February 1912. The general hospital was one of the best-equipped institutions in this part of the country. The three-story brick hospital, located in northwest Hoisington, had room for 30 patients and rooms maintained by the Missouri Pacific Railroad. The training school was established under the supervision of the superintendent of nurses, assisted by a competent corps of physicians. The courses took three years to complete.

Lind Hospital & Training School, Hoisington. Photo courtesy Clara Barton Foundation.

During the city’s early years, entertainment included one-night shows and weekly stands at the opera house. Many of the top entertainers of the day performed in the opera house, including popular hypnotism shows. Soon, Hoisington got its first movie theater, and local girls were hired to sing and play the piano during the movies.

In 1917, the dirt streets began to be paved.

On October 10, 1919, Hoisington was hit by a tornado. It killed Ellen Cravens, her baby, and H.B. McCurdy. John Rearick was injured and later died as well. The tornado damaged the Y.M.C.A., destroyed many buildings on lower Main Street, and damaged many homes before moving northeast.

Natural gas was discovered in the area in 1929, followed by oil in the 1930s.

In 1933, the First National Bank, the oldest bank in Barton County, was said to have been robbed by none other than Pretty Boy Floyd and his gang. After forcing C.P. Munns and M.W. Bennett to lie on the floor, face down, the gang made their getaway with more than $2,500 in bonds and money.

In February 1933, the home of George Ford in El Dorado was raided. Two men were said to have run from the house when the raid began, and one was reportedly “Pretty Boy.” However, Ford always denied it. During the raid, high-powered rifles and machine guns were found, and four men were arrested, all of whom were on the F.B.I.’s wanted list. Ford later surrendered some bonds allegedly issued by a bank in Hoisington. He was arrested and charged with robbing the bank.

South Hoisington accounted for the county’s most significant population growth until World War II, when an airbase was constructed in nearby Great Bend. Many of the people who moved to South Hoisington migrated from the South in the 1920s and 1930s. They came to work for the railroad and escape Ku Klux Klan members who targeted blacks.

Referred to as South Town, the community did not receive the benefits of paved streets, utilities, street lights, or law enforcement from Hoisington. It was also prone to flooding when Blood Creek and Shop Creek spilled over.

The town gained a bad reputation in the dry, conservative Christian county as some people made their living offering alcohol, gambling, and prostitution. One business called South Haven, better known as The Big House, provided all these amenities. Ironically, the two-story white house, centrally located in the little community, did not allow black customers — only white ones. This ensured more profit for its African American owners. Police raids were common, and illegal businesses would be fined, only to continue operating afterward.

Along its dusty streets, there was also a grocery store, a gas station, a Baptist church, a sale barn, beer joints, and a cafe. Indeed, not all 200 community members were involved in illegal activities. The First Baptist Church, with its choir, social activities, and youth groups, was a mainstay for many members.

These were prejudicial times for South Hoisington, also referred to as “the other side of the tracks.” Though its children attended the public schools in Hoisington, they could not ride the bus to school. Other activities were segregated, including not trying on clothing in stores, a separate section in the movie theater, having to take the orders “to go” at the soda fountain, and African Americans were not allowed in Hoisington after sundown. For the people of South Hoisington, moving north of the tracks was not an option.

The Great Bend Tribune often reported fighting, shootings, and prostitution. One report included a shooting death after an argument during a dice game.

Hoisington’s population peaked in 1960 at 4,248.

Problems continued in South Hoisington through the 1970s and into the 1980s. In October 1973, the Great Bend Tribune reported that Kansas Attorney General Vern Miller, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation director, and other officials raided the area, including the Big House, where they confiscated dice, marked cards, liquor, beer, money, and weapons.

Over the years, South Hoisington’s youth moved away, and another big flood in the 1980s caused most of the Black community to leave.

On April 21, 2001, Hoisington suffered another large tornado ripping through the city. In its wake, one person was killed, and 28 were injured. Some 200 homes and 12 businesses were destroyed, and 85 homes were severely damaged.

Over time, the railroad removed the boxcars in South Hoisington, and the area became a haven for illegal dumping. Work began in 2006 to clean up the area, which had become one of the state’s biggest dumpsites. After razing most of the residences, the Big House, and the church’s remains, 3,268 tons of waste material were removed at a cost of $400,000. Today, nothing is left but a few shacks, empty roads, and grassy plains.

The city of Hoisington and the Missouri-Pacific Railroad were linked in growth and economics for the better part of a century until the rail mergers of the 1980s began. The rail line then became part of the Southern Pacific and, finally, the Union Pacific. Today, the line is leased to Central Kansas Railroad and operated as a short-line railroad.

Many of the families who now live in the Hoisington area are descendants of those who came to the area at the railroad’s instigation, either to farm or to work in its shops or on its trains.

Today, Hoisington is home to about 2,700 people.

More Information:

City of Hoisington

109 E. First St., P.O. Box 418

Hoisington, KS 67544

620-653-4125

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated Novemberr 2025.

Also See:

Great Bend – Booming on the Santa Fe Trail

Sources:

Biographical history of Barton County, Kansas, published by the Great Bend Tribune, Great Bend, KS, 1912.

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

City of Hoisington

Genealogy Trails

Great Bend Tribune

Hutchison News

Wikipedia