Arkansas City, pronounced Ar-kan-sas, is located in Cowley County, Kansas, at the confluence of the Walnut and Arkansas Rivers.

The site had previously been home to a Wichita Indian village called Etzanoa, which flourished from 1450 to 1700 and had an estimated population of 20,000. When Spanish conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s expedition visited central Kansas in 1541, he dubbed the Wichita settlements “Quivira.” When New Mexico Governor Juan de Onate visited in 1601, they called the inhabitants Rayados, meaning “striped” in Spanish. The Wichita people were noted for the straight lines tattooed onto their faces and bodies.

The founders of Arkansas City arrived at the site on January 1, 1870, and Walnut City was platted the same year. However, the name was changed to Arkansas City when a post office was established on May 16, 1870. G. H. Norton served as the first postmaster.

The first building erected was a log house by G.H. Norton. The second was C.R. Sipes’ hardware store, followed by a frame building as a grocery by L. Goodrich. The first general store was opened in 1870 by G.H. Norton, who bought a stock of goods and began business in their cabin. The first drug store was opened by Eddy & Keith; the first hotel was opened by R. Woolsey, who also started a livery stable. H.D. Kellogg was the first physician, W.P. Hackney the first attorney, and P. Beck the first blacksmith. In the spring of 1870, W.M. Sleeth set up a sawmill.

Although surrounded by bands of hostile Indians, the settlement was unmolested. This immunity was mainly earned through the efforts of Henry Norton, who arrived in 1870. His honesty in dealing with the Indians immediately won their friendship and, eventually, their unreserved confidence. He went to their villages unaccompanied and was permitted to see their religious ceremonies. The Indians visited the settlement frequently, buying supplies and trading furs and horses at his invitation. Occasionally, they came in their finest regalia and entertained the settlers with tribal songs and dances. The whites gave them colored beads, tasseled handbags, plumed hats, and barbecued meat in payment.

By the end of 1870, the settlement boasted several stores and houses, two sawmills, and a newspaper called the Arkansas City Traveler. The community in these years was a rendezvous for horse thieves who stole stock from settlers in Kansas and drove them to Oklahoma. Buffalo Bill Cody, then a U.S. Marshal, made the vicinity his headquarters during the early seventies.

The first school was taught in 1871 by T. A. Wilson in a house that cost about $400.

The town was incorporated on June 10, 1872, and A.D. Keith was chosen as the first mayor. The same year, the Cowley County Bank was established, and the Walnut Mill was built on the Walnut River. Located about a mile northeast of the city, it was constructed by A.A. Newman and had a capacity of 100 barrels of flour per day. Power was furnished by an 80-horse-power engine and by four Chase water wheels. The cost of the mill was $20,000.

A new school building was erected in 1873 for $10,000. The Methodist Episcopal and United Presbyterian Churches were built in 1874, and more churches followed.

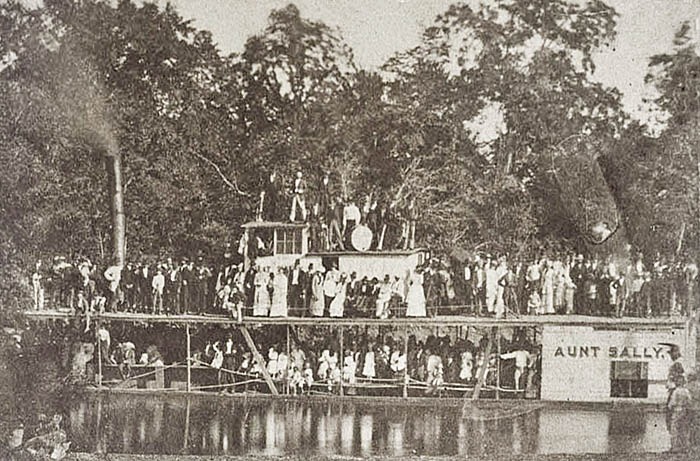

Aunt Sally Steamboat in Arkansas City, Kansas, 1878.

The steamboat Aunt Sally, the first to ascend the Arkansas River to Arkansas City, arrived on a Sunday morning in June 1878. Services were in progress at the village church, but the pastor and the congregation rushed out to welcome the boat at the first sound of the steamer whistle. Local merchants, intent on developing an inland shipping point, promptly purchased the Kansas Miller. On its first trip, the vessel grounded on a sandbar. Subsequent journeys were unsuccessful, and the Kansas Miller renamed the Walnut Belle, was converted into a pleasure boat.

For a few years, the growth was comparatively slow. However, in December 1879, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad completed a line to Arkansas City, after which the growth was more rapid and substantial. Following this road came the Kansas Southwestern, the Missouri Pacific, the Midland Valley, and the St. Louis and San Francisco lines, providing transportation facilities as good as those found in any city of its size anywhere.

With the advent of railroads, manufacturing became an important industry. A five-mile canal connecting the Walnut and Arkansas Rivers provided water power.

Another newspaper, the Arkansas Valley Democrat, was started in July 1879 by C.M. McIntire. The Creswell Bank began business in September 1880. by that time, Arkansas City had a population of 1,012.

The Canal Company was organized on January 12, 1881, for $50,000. The company aimed to build a canal from the Arkansas River to the Walnut River and gain power for milling and other purposes. A dam 900 feet in length was built across the Arkansas River, and the canal, which ran near Arkansas City, was completed to the Walnut River.

The Canal Mills were built in April 1882 for $18,000. With power furnished by the canal, the mill had a daily capacity of 150 barrels of flour. The Spears Mill was built the same year by William Spears & Co. for $8,000. It provided 75 barrels of flour daily.

The discovery of gold in the region in the 1880s stimulated Arkansas City’s growth. Assays indicated rich deposits, and the community seethed with activity. However, mining operations revealed little metal, and the boom soon subsided.

In 1886, two steel barges were constructed to navigate the Arkansas River. Soon, the steamers carried as much as 100,000 pounds of Kansas flour between Arkansas City and Fort Smith, Arkansas, on every trip.

In 1889, Arkansas City was one of the starting points for the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889. This run began the disposal of Unassigned Lands left vacant after the Civil War. In the spring of 1889, most would-be settlers massed in camps at the Kansas border towns, mainly at the railroad towns of Arkansas City and Caldwell. As the morning of April 22, 1889, dawned bright and clear, an estimated 50,000 people surrounded the Unassigned Lands. It was a day of chaos, excitement, and utter confusion as men and women rushed to claim homesteads. The “Eighty-Niners claimed an estimated 11,000 agricultural homesteads.”

An even more exciting event occurred in 1893 when the renowned Cherokee Strip was opened. The prize on this occasion was 8,000,000 acres of fertile ranch and farmlands. The starting point was the Kansas-Oklahoma border – four miles south of Arkansas City. Some months before the big land race, Arkansas City was the rendezvous point of 100,000 eager settlers who made plans and “big deals” before the first pistol shots were fired, signaling the race’s start at noon on September 16, 1893.

Afoot, on horses, in heavy lumber wagons, buggies, covered wagons, and all manner of horse-drawn vehicles, the settlers lined up to await the gunshot, which signified that the Strip was open. Impatient settlers inspected wagon wheels, harnesses, and saddles in a last-minute checkup. At high noon came the signal, and the boomers dashed across the line. The row held unbroken for an instant, and then, as settlers on fast horses outdistanced the others, it splintered into a tangle of wagons, buggies, and shouting drivers.

By the early 1900s, Arkansas City had lost its frontier aspect and had become a conventional market town. The discovery of oil nearby in 1914 and the post-war years altered the economic course of the city. Indians, made rich by wells brought in on their lands in northern Oklahoma, came to Arkansas City to splurge. They came by train, horseback, or even on foot and returned to their homes in gleaming new automobiles piled high with gaudy wares.

By 1910, several manufacturers produced cement, flour, feed, brooms, paint, and alfalfa meal. The city also had a meatpacking establishment, planing mills, an ice factory, creameries, five banks, an opera house, which cost about $100,000, an electric lighting plant, a fire department, a street railway, a good sewer system, and two beautiful public parks.

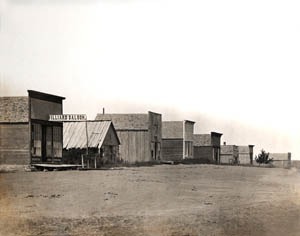

Summit Street, Arkansas City, Kansas, 1890. Touch of color LOA.

The public school system comprised four modern ward school buildings and a high school building that cost about $40,000. Several fine churches added to the city’s beauty. The jobbing trade covered a large territory, and the press was well represented by two daily and three weekly newspapers. By that time, the town was home to 7,508 people.

In 1922, Arkansas City Junior College was established. For 30 years, the college had facilities in the basement of Arkansas City High School. In 1950, Galle-Johnson Hall began to be built, and ten years later, its name was changed to Cowley County Community College. Today, the school offers multiple majors and career pathway possibilities to prepare students for transfer to a four-year program or to enter the workforce with a two-year job-ready degree.

During the 1920s, Arkansas City had an active group of Ku Klux Klan. The group was primarily concentrated in south-central and southeast Kansas. The state shut down the group, and most Klans disbanded by 1927.

The city’s official fall festival, Arkalalah, was inaugurated in 1928. This annual event still draws thousands of visitors each October and features a queen, a carnival, dozens of homegrown fair food vendors, and a spectacular parade.

The town’s population peaked in 1930 at 13,946 people.

By the late 1930s, Arkansas City had two flour mills, a meatpacking plant, foundries, creameries, a sand and gravel plant, overall factories, and an oil field machine shop. It also became a shipping and refining center for the area’s oil fields. Long lines of tank cars emerged from the city on its four railroads, and freight yards were piled high with incoming shipments of oil machinery and pipeline supplies. The business district had modern shops with tile facades and older structures of native limestone.

The city prospered through much of the 20th century, but by the 1980s, the community began to face economic challenges. The railroads shifted many of their crews to other stops; the old Rodeo meatpacking plant, which was Morrell Meats for a short time, closed. The only passenger train that served the city, Amtrak’s Lone Star, was discontinued. In 1996, Total Petroleum closed its refinery, losing 170 jobs.

By 2003, other large employers in Cowley County had closed operations, including the Crayola plant, which lost 400 jobs. The nearby Winfield State Hospital and Gordon Piatt Industries were also closed, resulting in a combined loss of 973 jobs.

Business Buildings in Arkansas City, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

However, Arkansas City recovered and is now home to state-of-the-art meat processor Creekstone Farms Premium Beef LLC, which employs over 700 workers. Several smaller manufacturing companies have expanded their operations, while new start-ups have also been located in Cowley County.

Today, the city has a population of 11,974. Arkansas City is three miles north of the Oklahoma border and 12 miles south of Winfield, the county seat.

While in Arkansas City, check out the Cherokee Strip Land Rush Museum. This museum honors those who participated in the Cherokee Strip Land Rush of September 16, 1893, and preserves the area’s history. The museum hosts many activities yearly, including a melodrama dinner theater sponsored by the Cherokee Strip Players. You can catch a re-enactment or attend a summer camp activity.

The recent discovery of Etzanoa, the Lost City, has brought heightened interest to the museum, which offers tours to the Etzanoa grounds. This place, called the “Great Settlement,” was lost in time by Spanish explorers in 1601. However, it has recently been rediscovered. Etzanoa was once inhabited by 20,000 ancestral Wichita Indians and is thought to be the second-largest settlement in North America in the early 1600s.

More Information:

Arkansas City

106 S. Summit St.

Arkansas City, KS 67005

620-442-0230

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

Arkansas City

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Federal Writer’s Project, Kansas, A Guide to the Sunflower State, Viking Press, New York, 1939.

Oklahoma History

Wikipedia