Not until Hernan Cortes reached Anahuac, the capital of the Aztecs, in 1521 was the buffalo known to Europeans. At that time, Montezuma had a well-appointed menagerie, and among the animals of his collection, the greatest rarity was the “Mexican Bull,” a wonderful composition of diverse animals. “It has crooked Shoulders, with a Bunch on its Back like a Camel; its Flanks dry, its Tail large, and its neck covered with hair like a lion. It is cloven-footed, its Head armed like that of a Bull, which it resembles in Fierceness with no less strength and Agility.”

This is probably the first description of the American buffalo in print. In 1530, Cabeza de Vaca encountered buffalo in a wild state in Texas. He also left a description of them, telling of their meat’s quality and the uses of buffalo robes.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, in 1542, reached the buffalo country on his way to Quivira and traversed the plains “full of crooke-backed oxen, as the mountain Serena in Spaine is of Sheepe.”

In 1612, an English navigator named Samuel Argoll mentions meeting with buffalo while on a trip to Virginia, discovering them some miles up the Potomac River, probably near present-day Washington, D.C. Father Hennepin encountered buffalo in 1679 while on a journey up the St. Lawrence River. Marquette said the prairies along the Illinois River were “covered with buffaloes.” Lewis and Clark, on their return trip down the Missouri River in 1806, mention having to wait an hour for a herd that was then crossing the river.

Colonel Richard I. Dodge, in his Plains of the Great West, describing a herd met in Kansas, said: “In May 1871, I drove in a light wagon from old Fort Zarah to Fort Larned on the Arkansas River, 34 miles. At least 25 miles of this distance was through one immense herd, composed of countless smaller herds of buffalo then on their journey north. The whole country appeared one great mass of buffalo, moving slowly to the northward. The herds in the valley sullenly got out of my way and, turning, stared stupidly at me, sometimes at only a few yards distance. When I had reached a point where the hills were no longer than a mile from the road, the buffalo on the hills, seeing an unusual object in their rear, turned, stared an instant, then started at full speed towards me, stampeding and bringing with them the numerous herds through which they passed and pouring down upon me all the herds, no longer separated, but one immense compact mass of plunging animals, mad with fright, and as irresistible as an avalanche. Reining up my horse, I waited until the front of the mass was within 50 yards when a few well-directed shots from my rifle split the herd and sent it pouring off in two streams to my right and left. When all had passed me, they stopped, apparently satisfied, though thousands were yet within range of my rifle and many within less than 100 yards. Disdaining to fire again, I sent my servant to cut out the tongues of the fallen. This occurred so frequently within the next ten miles that I had 26 tongues in my wagon when I arrived at Fort Larned. I was not hunting, wanted no meat, and would not voluntarily have fired at the herds. I killed only in self-preservation and fired almost every shot from the wagon.” This herd is estimated to have numbered about 4,000,000 head.

Accounts are numerous of the existence of buffalo in other remote localities, but on the Great Plains, they throve best and were to be found in the greatest numbers. The mating season occurred when the herd was on the range when the calves were from two to four months old. During the “running season,” the herds came together in one dense mass of many thousands — in many instances, so numerous as to blacken the face of the landscape.

Kearney, Nebraska, was probably very near the center of the buffalo range, and every year, the Plains Indians had their buffalo hunt. The buffalo supplied many of their wants, the skins being carefully tanned to supply clothing, bedding, and covers for tepees; the meat not intended for immediate consumption was stripped off the carcass, carefully dried, and thus made available for use until the next hunt. The hides of the old bulls were used as a covering for a watercraft known as “bull boats” — being carefully stretched over a round framework, the hairy side within. These boats were constructed more easily than by hollowing out logs.

Of all the four-legged animals that have lived on the earth, probably no other species has ever marshaled such innumerable hosts as those of the American bison. It would have been as easy to count or estimate the number of leaves in a forest as to calculate the number of buffalo living at any given time during the species’ history before 1870.

From 1820 to 1840, it has been estimated that approximately 652,275 buffalo were killed by buffalo hunters, the total value of which, at $5 each, would be $3,261,375. Where Indians killed one for food, hide, and tongue, hunters killed 50. This incessant slaughter was kept up year after year, thousands of hunters — whites and Indians — being employed for no other purpose than to kill as many as they could.

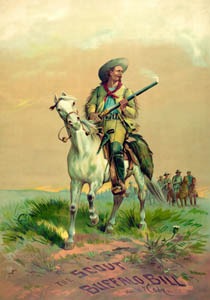

Buffalo Bill Cody was once engaged in this business and is said to have killed 4,280 in 18 months, while thousands of others were likewise engaged, of whom no record is had. In 1871, several thousand hunters were in the field, and it is estimated that 3,000 to 4,000 buffalo were killed daily.

The building of the Pacific railroads divided the buffalo into two large herds that ranged on either side of the Platte River. The estimated numbers in these herds at this time were about 3,000,000 each, and western men never thought in those days that it would be possible to exterminate such a mighty multitude. But, the same improvident work of destruction continued, and by 1875, the southern herd had been exterminated. The northern herd in 1882 was thought to number about 1,000,000 head, but by 1883, it was almost annihilated, and Sitting Bull and a few white hunters that year had the distinction of killing the last 10,000 that remained.

Indians, who foresaw the destruction of their food supply, and some bloody wars were the result. During the construction of the Kansas Pacific and Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroads, the buffalo were so numerous as to impede work. On more than one occasion, trains were derailed by running into herds.

After the extermination of the southern herd, a new industry sprang up, the bones of the slaughtered millions being carefully gathered and shipped back east, where they were ground into fertilizer for the impoverished farms of the older sections. Thousands of carloads were shipped, the average price paid from $4 to $6 a ton.

Charles J. “Buffalo: Jones, for many years a resident of Kansas, succeeded in a measure in domesticating the buffalo and made experiments in crossing them with the Galloway breed of cattle, the product of which was called the Catalo, taking primarily the characteristics of the buffalo.

To save the animals from destruction, the United States secured several buffalos and placed them in Yellowstone National Park, where they could be free from molestation. This small herd increased very slowly owing to losses of calves through predatory animals. By the early 1900s, the buffalo had entirely disappeared outside of a few public and private collections.

~~

Today, buffalo can once again be seen in several places in Kansas. The Maxwell Wildlife Refuge is one of the few places where wild buffalo can still be seen. The refuge is six miles north of Canton, Kansas, just off Highway 86. There are also several private ranches where herds can be seen; some even hold buffalo hunts. Many others sell buffalo meat both locally and nationally.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Adventures in the American West

Plains Indians – Surviving With the Buffalo

About the Article: Most of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text that appears on this page is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing have occurred.