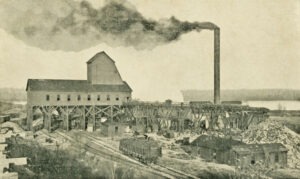

Pittsburg, Kansas Coal Mine.

Coal mining began in Kansas in 1827. Bituminous coal deposits were widely distributed in eastern Kansas. Though the heaviest mining took place in southeast Kansas in the counties of Cherokee, Crawford, and Bourbon, other mines were located in other parts of the state, including one large area in Osage County and in Cloud, Republic, Leavenworth, and Atchison Counties.

Coal was probably mined in Kansas on a hillside near Fort Leavenworth as early as 1827. By the late 1850s, Missourians were mining coal for use by blacksmiths near what is now Weir in southeastern Kansas. Before and after the Civil War, coal production became central to the expansion of railroads because it burned hotter and was less bulky than wood. To meet the demands of the railroads, strip mines were opened during the 1870s in Bourbon, Cherokee, and Crawford counties.

Coal was also mined in Osage County in east-central Kansas from 1885 to 1969. In 1889, Osage County had 118 coal mines that employed more than 2,200 people and produced almost 400,000 tons of coal. For many years, this was the primary fuel source for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, whose main line passed through Osage County.

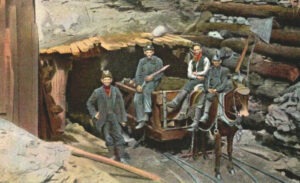

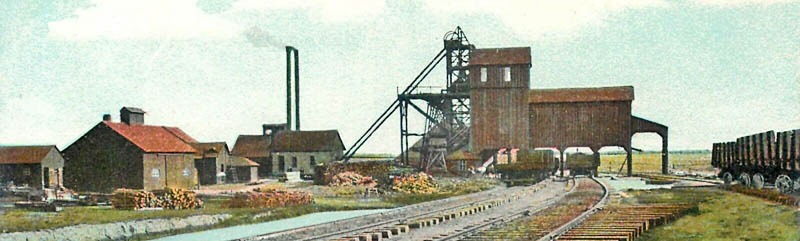

Before the completion of the first coal shaft mine in 1874, there were two forms of mining in the area: drift mining and strip mining by animate power. The small, early drift or adit mines were sited along outcroppings of coal beds on the hillslopes and sides of ravines. Because of their burrowed-in appearances along the outcrop, the early day drifts were appropriately called “gopher hole” mines.

In the early days, surface or strip mining was carried out by teams of guided mules and horses pulling scraps and plows over coal seams that lay under soil and rock, called overburden. The thin overburden was removed, and wagons removed the exposed coal. These two forms of early-day mining were suitable for reaching the exposed or shallow-lying coal seams. Still, eventually, the two methods proved ineffective for reaching the deeper-lying coal.

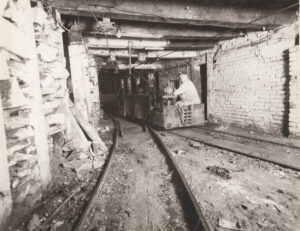

In 1874, the first mineshaft in Cherokee County was dug, and coal was excavated using the room-and-pillar system in which substantial pillars of coal are left standing to support the overlying rock. This year was the most significant for coal mining in southeastern Kansas. It brought the construction and opening of the first underground shaft mine near the present-day Scammon. The completion of this form of underground mine signaled the beginning of an important phase of coal mining in Cherokee County and the adjacent Crawford County. In the following years, other shaft mines were opened in the coal-bearing areas of the two counties. Underground mining was instrumental in the historical development of the Cherokee-Crawford coal field by having a stimulating impact on employment, demographic movements, the transportation network, commerce, and forms of settlement within the coalfield.

In 1879, a coal mine began operating at the Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing, Kansas. Excavation of the 720-foot mine shaft began on November 26, 1879, and coal was reached on January 18, 1881. The mine, the last deep mine to operate in Leavenworth County, utilized the longwall mining system rather than the room-and-pillar system typical of the coal mines in Southeast Kansas. By 1927, the KSP mine had approximately 21 miles of tunnels. Initially, the coal mined at the penitentiary was furnished to state educational, charitable, and correctional institutions, with the surplus output being sold to private individuals and contractors. The sale of surplus coal was discontinued after 1899 because the mine’s entire output was needed to meet the demand of state institutions. The peak of the mine’s operation occurred between July 1, 1932, and June 30, 1934. During that time, the amount of coal produced totaled 171,982 tons, and a daily average of 445 inmates were employed in the mine. Production ceased 13 years later because the mine was no longer economically viable. The mine shaft was sealed on October 1, 1947.

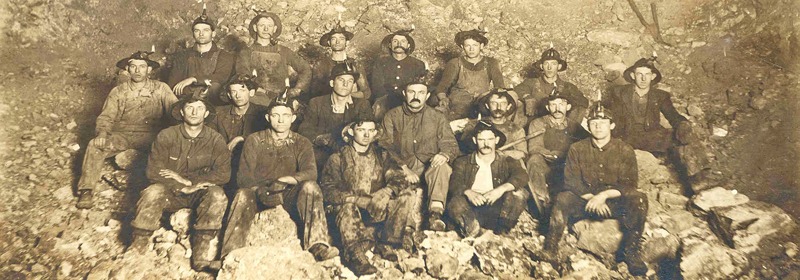

In 1883, the state inspector of coal was established to protect workers from dangers. As part of the regulation, boys younger than 12 were prohibited from entering mines.

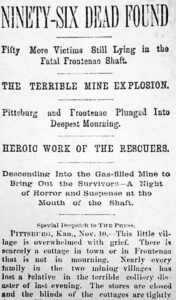

An explosion at a mine near Frontenac in 1888 resulted in the death of 44 men and boys in Kansas’ worst mining disaster. It led to further regulations to improve working conditions and increase safety for the miners.

“The violence of the shock rocked Pittsburg and all surrounding territory. Half an hour after the explosion, a ragged, bleeding man staggered into Pittsburg. He said that all the men in the mine except himself and one other had been killed.”

— Pittsburg Headlight, November 10, 1888.

Underground mining was dominant there for several decades. With an average thickness of three feet, the Weir-Pittsburg coal, the thickest and the most important seam in the coalfield, was mined by shaft mining down to the maximal depth of 285 feet. This coal bed became the most extensively mined coal bed in Kansas history. The number of employees in underground mines of the Kansas portion of the coalfield reached almost 10,000 during the early years of World War I.

Strip mining became the preferred method in southeastern Kansas in the 1930s, although underground mining continued there until 1960 and in Osage County until 1964.

Overlying soil and rock, called overburden, are stripped away using power shovels to expose coal beds too thin to be mined underground during strip mining operations. In southeastern Kansas, ditches were dug as much as 100 feet deep to reach the coal. One of the world’s largest power shovels, Big Brutus, was operated 24 hours a day in Cherokee County from 1963 to 1974. It is now the museum’s centerpiece featuring the southeast Kansas mining industry.

Strip mining creates deep ditches and high ridges. Before widespread land reclamation was required in 1969, disturbed land in Kansas was abandoned when mining operations stopped. Trees and brush took over the ridges, and the trenches filled with water.

There were over 100 sites of former coal mining communities clustered near shaft mines in the Cherokee-Crawford coalfield. Several of the settlements survived to become rural and urban communities. Mining camps were generally built by the coal companies to provide quick and ready housing to accommodate the large numbers of miners and their families. They adopted names like 42 Camp, Blue Goose, Buzzard’s Roost, Dogtown, Foxtown, Frogtown, Little Italy, Pumpkin Center, Red Onion, and Water Lilly. The camps provided a place to live that was close to the mine. In addition to “company houses,” other structures were often built by the mine operators, including a “company store,” a community hall, churches, schools, rooming houses, hotels, blacksmiths, and saloons. The smaller and more temporary camps naturally possessed fewer structures and services than larger camps. During the prosperous years of mining, company camps were much more numerous in the coalfield than were non-company camps. The mining communities ranged from fewer than 50 individuals to over 1,000 in such places as Arma, Pittsburg, Frontenac, Mulberry, Scammon, and Radley. However, the majority remained small and individually had, during their peaks, a maximum of a few hundred inhabitants. The camps were commonly moved, wholesale or in part, after the dissolution of the underground mines around which the camps initially clustered. The houses, shacks, and other buildings, after being disassembled, were commonly moved to new camps on railroad flatcars or on huge, flat wagons pulled by mules and horses. Those buildings that were not moved were sold or left to fall into a state of disrepair.

The establishment and growth of mining camps in the coalfield began in the late 1870s and probably lasted until about 1920.

In 1962, Big Brutus, an enormous power shovel, was shipped to Cherokee County. Purchased from the Bucyrus-Erie Company of Milwaukee, Minnesota, the machine’s cost was $6.5 million. It was shipped on 150 railroad cars, and once there, it took a year to build. The machine towered 16 stories high and weighed 11 million pounds when complete. When the work was completed in June 1963, Big Brutus, with its 90-cubic-yard shovel, could move 150 tons of coal in one bite, enough to fill three railroad gondolas.

Although designed to last a quarter of a century, the big shovel was used for only a decade. The coal in the area had been depleted, and coal prices made digging what was left unprofitable. By 1973, the shovel was obsolete. Today, it is part of the Big Brutus Museum at 6509 NW 60th Street in West Mineral, Kansas. Big Brutus was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

In 1969, the Kansas Legislature passed regulations requiring coal companies to reclaim mined land and make it productive again. More stringent federal regulations followed. On land strip-mined after 1969, mining companies had to smooth ditches, bury mine waste that polluted water, replace topsoil, and plant grass or crops. Thousands of acres that were strip mined before regulations were enacted are now part of the Mined Land Wildlife Area that encompasses 1,000 strip mine lakes and is maintained by the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks, and Tourism.

In February 2016, the last mining company in Kansas, at least temporarily, ceased operation.

Kansas Coal Miners.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, April 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Home Authors; A Twentieth Century History and Biographical Record of Crawford County, KS, Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, 1905

Former Mining Communities of the Cherokee-Crawford Coal Field of Southeastern Kansas by William E. Powell, Summer 1972, Kansas State Historical Society

Kansapedia

University of Kansas