Towns & Places:

Bronson

Fort Scott – County Seat

Fulton/Osaga

Mapleton

Redfield

Uniontown/Turkey Creek

Fort Scott Military Post – National Historic Site

Bourbon County, Kansas, in the Civil War

One-Room, Country, & Historic Schools of Bourbon County

Bourbon State Fishing Lake

Cedar Creek Lake

Elm Creek Lake

Fort Scott Community College Lake

Rock Creek Lake & Waterfall

Lake Fort Scott

Little Osage River

Marmaton River

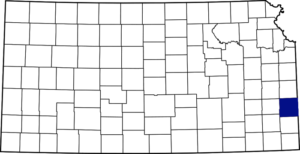

Bourbon County, Kansas, is located in the southeastern part of the state, bordering Missouri. Fort Scott is the county seat and most populous city. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 14,360. Named after Bourbon County, Kentucky, it was one of the 36 counties created by the first territorial legislature in 1855.

Located in the third tier north of Oklahoma, it is bounded on the north by Linn County, on the east by the State of Missouri, on the west by Neosho and Allen Counties, and the south by Crawford County.

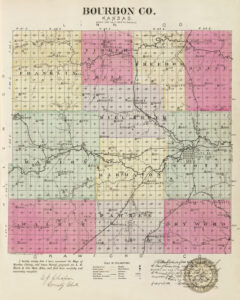

The general surface of the country is undulating, the highest hills being found in the northwest portion, where they rise to about 200 feet above the Marmaton River. The valleys of the streams average about a mile in width, and these bottomlands comprise about one-third of the area. Timber belts vary in width along the streams and contain species such as hackberry, hickory, oak, pecan, and walnut. On the uplands and in some of the lower lands, hickory, maple, poplar, and willow have been planted. The main water courses are the Little Osage River, which flows east a few miles south of the northern boundary, and the Marmaton, which flows from west to east through the central portion of the county. The Little Osage has several tributaries flowing into it from both north and south, the main stream being Limestone Creek in the northwest part of the county. The main creeks flowing into the Marmaton River from the north are Turkey and Mill Creeks, and from the south, Yellow Paint Creek, which also has several small tributaries. Drywood Creek flows across the southeast corner.

The soil was deep and fertile, underlain by sandstone and limestone at various depths. There were once quarries at Redfield, Gilfillan, and near Hiattville. Good-quality cement was manufactured from stone found near Fort Scott. Mineral paint and clay for brick were also plentiful. Natural gas was found in Bourbon County in 1867 and was utilized for lighting and heating. There were numerous manufacturing plants, principally at Fort Scott.

The territory within Bourbon County’s limits formed initially part of the reservation of the New York Indians. The reservation was ceded to the government before the organization of the Kansas Territory, when the lands were opened to white settlement. One of the first white men to enter the present limits of the county was Lieutenant Zebulon Pike in his expedition of 1806.

For some time before the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, settlers across the line in Missouri had been aware of the fertile soil in Bourbon County. They had only waited for the territory to be organized to rush across the line and claim their land. A majority of the early settlers were pro-slavery men, but there were also men from the Northern states who were free-soilers in politics, though for some years, they were in the minority. Some men who settled in the county in 1854 were Gideon Terrell, William, Philander Moore in Pawnee Township, and Nathan Arnett in Marmaton Township. In 1855, Guy Hinton settled in Walnut Township, and James Guthrie, Cowan Mitchell, John, and Robert Wells in Marion Township. Others who came during the next two years were Samuel Stephenson, Charles Anderson, John Van Sycle, D. D. Roberts, Joseph Ray, H. R. Kelso, Gabriel Endicott, David Claypool, and Edward Jones, who built the first sawmill in what is now Marmaton Township, the second mill in the county, the government having one on Mill Creek. David Endicott, one of the first to locate the area, assisted in the land survey.

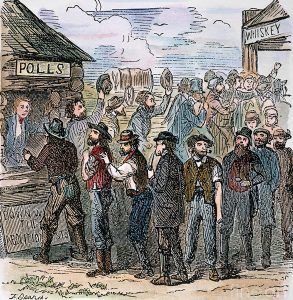

Voting in Kansas.

Scarcely had the first settlers become established when trouble over politics began. It is estimated that on March 30, 1855, at least 300 armed Missourians came to the Fort Scott precinct to cast their votes, while there were probably fewer than 30 legal voters in the precinct. Early in the spring of 1855, a party of men came to Bourbon County from Carolina, under the leadership of George W. Jones, to assist in making Kansas a slave state. They were sent out under the auspices of the Southern Emigrant Aid Society. They were mild-mannered at first and went through the county, visiting the Free-State settlers, asking them for their opinions on the political questions of the day, how they were supplied with arms and ammunition, and inquiring about the good land in the territory. In this way, a complete list of the free-state men was made. Later in the year, nearly all the men on the lists were made prisoners, and while thus held, they were advised to leave the territory. As soon as they left, pro-slavery men took their claims.

The first schools in the county were private ones at Fort Scott, which opened in 1857, but the district school system was not organized until 1859. One district, later known as No. 10, was organized on December 10. Four more districts were organized in 1860, and since then, progress in education has been steady. In 1910, Bourbon County had a public school system as fine as any in the state.

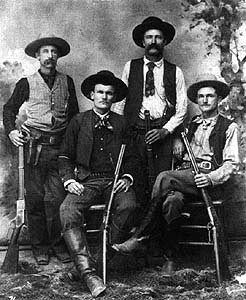

Early in August, a party of Texas Rangers arrived at Fort Scott. Accompanied by a considerable number of citizens of that town, they started northward through the border counties, intending to have “fun” at the expense of the free-state settlers. Early in 1857, many free-state men who had been driven from their homes returned to Bourbon County. Several new settlers from the Northern states also came about this time, and as the free-state men grew in number, they also grew in confidence. To gain possession of the claims from which they had been driven, they organized a “Wide Awake” society in opposition to the “Dark Lantern” lodges of the pro-slavery men. Some of the most important leaders of this movement were J.C. Burnett, Captain Samuel Stevenson, and Captain Bayne. The meetings were held at different settlers’ cabins at intervals to evade surprise by the men of the “Blue Lodges.” When all the plans of the “Wide Awakes” were perfected, they notified the pro-slavery men who had seized claims that did not belong to them that they must leave. Most of the pro-slavery men realized that resistance would lead to severe difficulties if not bloodshed, and left, but some had to be driven off the claims by arms. The border strife continued in Bourbon County after nearly disappearing in other parts of Kansas Territory.

Texas Rangers.

As a matter of reprisal, some free-state men were arrested on various charges. The district court was presided over by Joseph Williams, a pro-slavery man. The adjustment of claims was referred to his court for a time and was usually decided in favor of the pro-slavery claimant. This caused great dissatisfaction among the free-state men and led them to take severe measures to secure the release of free-state prisoners held at Fort Scott. Another result of Judge Williams’ decisions was the formation of a “Squatter Court,” where free-state men heard cases of contested claims. Dr. Gilpatrick of Anderson County was appointed judge, and Henry Kilbourn was sheriff. The proceedings of this body were regular and dignified; its decisions were usually just, and the sheriff rigorously executed its decrees. The proceedings of the court were naturally distasteful to the pro-slavery men.

As a consequence, an expedition was organized and started under the command of Deputy United States Marshal Little to capture the court. The attempt failed, and four days later, on December 16, 1857, Little organized a posse of about 50 men for a second attempt. They approached the cabin of Captain Bayne, where the court was sitting, and a short distance from it, were met by messengers from the court, consisting of Major Abbott, D. B. Jackson, and General Blunt, who had been sent out under a flag of truce as Little was advancing. A parley was held, after which Little said that if the court did not surrender, he would open fire. The messengers returned to the cabin with the conference report. The decision was against surrender; the cabin was put in a state of defense. Some of the chinking between the logs was removed to form loopholes. Major Abbott told Little that they would not surrender, and if he advanced beyond a particular line, the free-state men would fire. Little advanced, however, received a volley from the cabin, which was returned, and then retreated half a mile. Four men were wounded, but Little called for a volunteer party and made a second attack with no better result, except that no men were hurt. Finding it impossible to take the “fort” without loss, the marshal returned to Fort Scott. The next day, he gathered a more significant number of men and again started for the fort, but upon arriving, found the cabin deserted, as the court had moved to the Baptist church at Danford’s mill.

By December 1857, Captains Bayne and James Montgomery had successfully driven out of the district many of the pro-slavery men who unlawfully held claims. The parties driven out congregated at West Point, Marvel, Balltown, and Fort Scott, where their Blue Lodges flourished. From these centers, raids were made to harass the free-state settlers on Mine Creek, the Little Osage River, and the Marmaton River. Almost daily reports came of outrages committed by the Missourians, and the free-state men would ride upon errands of swift retaliation.

Late in December, two companies of U.S. cavalry were stationed at Fort Scott at the request of the residents, and order was restored in the district. However, in early January 1858, they were withdrawn, and trouble broke out again. On the night of February 10, 1858, Montgomery and a party of 40 men started for Fort Scott to punish some of the bitter pro-slavery men who had been persecuting Mr. Johnson, who lived in the town. On February 26, 1858, two companies of United States cavalry were again stationed in the town. As Montgomery always avoided conflicts with government forces, he began operating against the pro-slavery men in the country with the object of driving them into the city. It is estimated that as many as 300 families in the district were forced to flee their homes and take refuge in the towns. Captain Anderson, in command, could not protect them in their isolated settlements, and the result Montgomery wished was attained. But this was no one-sided guerrilla warfare, and it took all the sleepless vigilance and every resource of Montgomery, Bayne, and abolitionist John Brown combined to protect the free-state settlers against “the wolves of the border.”

On June 7, 1858, some of Montgomery’s men attempted to fire the Western Hotel in Fort Scott, but no one was hurt, and the fire was extinguished. On June 13, Governor James Denver arrived at Fort Scott. A meeting was held, and feelings ran high on both sides, but by the governor’s judicious treatment, peace was restored. The next day, a second meeting was held in Raysville, at which the governor proposed a compromise that restored peace for some time. Subsequently, a free-state man named Rice was arrested for the murder of Travis, who had been shot on February 28. This was regarded as a violation of the agreement made on June 15, and Montgomery determined to rescue Rice. Accordingly, he organized a party of 100 men, including John Brown, who wanted to destroy Fort Sumter. Still, as Montgomery’s primary purpose was to rescue Rice, he left Brown outside the town and proceeded without him. Rice was released, Mr. Little was killed, Montgomery’s men looted a store of a stock valued at about $7,000, and 12 citizens were made prisoners. The citizens then appealed to the governor for protection, and, since there were no troops to send, he advised forming a home militia for defense, a suggestion that was carried out. After the passage of the Amnesty Act, there was little further trouble along the border, and peace came to stay in Bourbon County.

After the Civil War began, a big Union demonstration was made at Fort Scott, which had been one of the bitterest pro-slavery towns. Party differences were set aside for the nation’s defense, and by mid-April, two companies had been raised on Drywood Creek, and two more were formed at Fort Scott in May. Other companies were raised at Lightning Creek and Mill Creek, and a company of home guards was organized. The most significant engagement during the war near Bourbon County was the Battle of Dry Wood Creek in Vernon County, Missouri, which took place late in September 1861 between Confederate forces under General Rains and Union forces under General James H. Lane. General Sterling Price’s army passed through the eastern part of the county in October 1864. While crossing the valley of the Little Osage, army members committed many outrages. For a time, the people of Fort Scott feared for the city’s safety. Bourbon County ranked fifth in the number of men who entered the militia during the war.

The county was organized on September 12, 1855, when S. A. Williams, the probate judge, administered the oath of office to Commissioners Colonel H.T. Wilson and Charles B. Wingfield. B. F. Hill was appointed sheriff, and William Margrave was deputy sheriff. On September 17, the following officers were appointed: James F. Farley, clerk; Thomas Watkins, justice; John F. Cottrell, constable. Governor Reeder had appointed William Margrave justice of the peace in December 1854, the first in the county. On October 15, four additional justices and three constables were appointed at the same time as A. Hornbeck was appointed treasurer; W. W. Spratt, assessor; and H. R. Kelso, coroner. In November, the county was divided into five townships. From the time of its organization until January 1858, the county’s affairs were in the hands of the county court, consisting of a probate judge and two commissioners. However, the form of government was then changed and placed in charge of a board of supervisors, one from each township. In 1860, it was again changed, and three commissioners took the place of the board. In 1855, the seat of justice was located at Fort Scott, as established by the act creating the county. In 1858, due to border troubles, it was changed to Marmaton by a special law of the legislature. An election was held on May 11, 1863, to determine the permanent location of the county seat. Fort Scott received the majority of votes cast and again became the county seat, a designation it has since retained.

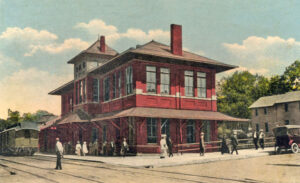

In 1865, the citizens voted to issue $150,000 in bonds to subscribe a like sum to the capital stock of the Missouri River, Fort Scott, and Gulf Railroad. The road was completed to Fort Scott in December 1869, and on January 7, 1870, the bonds were delivered to the road. In 1867, a proposition to vote for $150,000 worth of bonds to purchase the Tebo & Neosho Railroad stock was carried, but the commissioners decided it was not advisable to purchase the stock of this road. They ordered that $150,000 be subscribed to the capital stock of any road that would start at Fort Scott and run north of the Marmaton River in the general direction of Humboldt. This amount was subscribed to the stock of the Fort Scott & Allen County Railroad Company on the condition that the road should be completed west of the county by July 1, 1872. The Fort Scott, Humboldt & Western succeeded this road and requested the delivery of the bonds, but the conditions had not been met, and the bonds were issued to the Fort Scott, Humboldt & Western under that name.

Bourbon County’s population peaked in 1890 at 28,575.

In 1910, the county had about 125 miles of main-track railroad. The Missouri Pacific Railroad operated two lines — one running from east to west through the center, and the other crossing the county from north to southeast, both lines passing through Fort Scott. The St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad entered the northeast, passed through Fort Scott, and at Edward, the branches and both lines entered Crawford County. The Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway entered from Missouri, passed through Fort Scott, and then southwest into Crawford County.

In 1910, the county’s population was 24,007. The value of the farm products for the same year was $1,504,134. Corn was the principal crop, with a value of $754,039, and hay was second, with a value of $432,994.

In the next few decades, the county’s population dropped as farms grew and many people moved to larger cities.

However, agriculture and livestock are still large industries. The County’s leading crops today are milo, wheat, and soybeans.

Bourbon County has four large, man-made lakes, including Bourbon State Fishing Lake, which has a surface area of approximately 207 acres; Lake Fort Scott, four miles southwest of Fort Scott, which has a surface area of 350 acres; Elm Creek Lake, 15 miles southwest of Fort Scott; and Cedar Creek Lake, located approximately six miles west of Fort Scott.

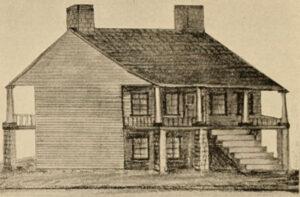

National Cemetery #1 was established by an act of Congress in 1862 and is located in Fort Scott. The National Park Service operates the Fort Scott National Historic Site, which contains many original and reconstructed buildings from the 1846 period. The fort hosts many annual activities that commemorate its history.

Fort Scott Community College, a public two-year college, was established in 1919. It is fully accredited by the Kansas State Department of Education and the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated April 2025.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War

Fort Scott Military Post – National Historic Site

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Bourbon County, Kansas

Cutler, William G.; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Kansas Post Office History