Fort Scott, Kansas, the county seat of Bourbon County, is situated in the southeast part of the state, four miles from the Missouri State line. It was located on the south bank of the Marmaton River and named for General Winfield Scott. As of the 2020 census, the population was 7,552.

In 1837, the old Military Road between Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, was surveyed, and provisions were made for a camp between two forts. However, it was not until 1842 that a fort was founded approximately midway between the two and named in honor of General Winfield Scott.

Soldiers at Fort Scott assisted with protecting the permanent Indian Frontier. Until the establishment of Kansas Territory, Fort Scott was attached to Bates County, Missouri, for administrative purposes.

The first settler was John A. Bugg, who located there as a sutler. Bugg became the first postmaster when a post office was established on March 3, 1843. The Fort Scott Post Office was the second one established in Kansas. That year, H. T. Wilson purchased a partnership in Bugg’s business and six years later purchased the entire stock while being made postmaster.

In 1854, the troops were withdrawn from the military post. The families of Colonel Wilson and Captain John Hamilton were the only ones not employed by the Government at the time. Colonel Wilson continued to conduct his store, which stood on Market Street. Colonel Thomas Arnett opened the first hotel in the city’s west block of the old Government buildings.

That year, Kansas Territory was thrown open to settlement, and several settlers came into Bourbon County from Missouri, many of whom settled at Fort Scott. Some of the first men included Dr. Hill, R. Elarkness, D. F. Greenwood, and Thomas Dodge. At that time, nearly all the land in the area belonged to the New York Indians; nothing could be done but to select and hold claims until they should, by purchase of or treaty with the Indians, be thrown open to settlement. Though several claims were taken, no effort was made to organize a town company until 1857.

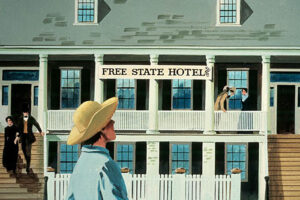

On May 16, 1855, the buildings erected by the Government at a cost of about $52,000 were sold at auction. One group of former officers’ quarters, afterward known as the Free State Hotel, was bought by A. Hornbeck for $500; Colonel H. T. Wilson purchased another building for $300; the next by Edward Greenwood for $505; and the next one farthest toward the east by J. Mitchell for $450, for a total of $1,755.

The first newspaper was published in Fort Scott, and the first in Bourbon County was in Southern Kansas in 1855. It was edited by a man named Kelley.

Lying only five miles from the Missouri Line, the town, before and during the Civil War, became the rendezvous for both Free Staters and pro-slavery sympathizers, and guerrillas and ruffians along the border plundered and stole from both sides.

Soon after the settlement of Fort Scott began, it was recognized as the leading pro-slavery town of southeastern Kansas, holding the same relation to the southeastern part of the territory that Atchison did to the northeastern.

Between 1855 and 1861, the citizens of Fort Scott experienced the violent unrest that preceded the Civil War on the Kansas and Missouri border. The violence, referred to as “Bleeding Kansas,” resulted from the national controversy concerning the extension of slavery into the new territories. On January 29, 1861, Kansas entered the Union as a free state, but the turmoil of “Bleeding Kansas” continued throughout the Civil War.

On June 8, 1857, the Fort Scott Town Company was organized and consisted of George A. Crawford, President; G. W. Jones, Secretary; H. T. Wilson, Treasurer; Norman Eddy, D. H. Wier, D. W. Holbrook, William R. Judson, T. R. Blackburn, and E. S. Lowman. Soon afterward, Dr. Blake Little was made a conditional member of the company, and Judge Joseph Williams purchased the interest of G. W. Jones. The town company purchased the claims of several others.

In July 1857, the government land office was opened in Fort Scott. The receiver was ex-Governor E. Ransom of Michigan, accompanied by George J. Clark, who was appointed register. In August, several settlers arrived, and the town began to grow. A plat of the town site was made immediately after that by O. Darling and a second one by O. Edwards.

A store was opened in the old quartermaster’s building by Dr. Blake Little & Son; John G. Stewart started a blacksmith shop; George A. Crawford, W. R. Judson, Sheriff Hill, and William Barnes each opened a saloon, and C. Dimon bought the Free State Hotel, which had become a popular stopping place for travelers. The first school taught in Fort Scott was a private one.

In 1857, a private school was taught, and during the following summer, Mrs. C. H. Haynes taught a school in the old hospital building.

One of the old fort’s officers’ quarters was occupied by the Free State Hotel in the late 1850s, so named because it was a favorite stopping place for such Free Staters as John Brown, Charles Jennison, Captain James Montgomery, and scores of other Free-State sympathizers. The hotel became nationally known through the columns of the New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore papers as the headquarters of Captain Montgomery, who had widely publicized raids upon pro-slavery sympathizers in the vicinity. Local tradition in Fort Scott asserts that the term Jayhawker originated with the patrons of the Free State Hotel.

Captain Montgomery took up Jayhawker as a nickname for his band and finally stuck it as a name for all of Kansas. The Western Hotel, a stopping place for pro-slavery men, stood directly across the Plaza from the Free State Hotel in the days preceding the Civil War. The rivalry between the two hostelries was as bitter as between the North and the South. Here, it is said, the Marais des Cygnes Massacre was plotted, and here, two pro-slavery men organized a Blue Lodge by which they hoped to drive Free State men from the Terri-tory by scaring them off their claims. The Free Staters, in turn, organized the Self-Protective Association headed by Captain Montgomery.

Friction between the two factions came to a head in October 1857 when Judge Joseph Williams of the United States District Court, a pro-slavery sympathizer, began to hear the lawsuits between the Free State and the pro-slavery men over homestead claims. Declaring that all decisions were going against the Free State claimants because of partiality shown by the court, the anti-slavery faction set up its court in a log cabin a few miles from town. This they called the “Squatters’ Court.”

Pro-slavery sympathizers arrested a man named Rice, who was charged with the murder of one of their comrades and held him at the Free State Hotel pending his trial in the district court. Montgomery, with about 70 men, returned to Fort Scott to release the prisoner. A storekeeper named Little, also a United States Marshal, fired into the group outside the hotel from the transom of his shop. Immediately, one of Montgomery’s men returned fire, shooting Little through the forehead as he looked out. Shots rang out through the Plaza for several minutes. Montgomery and his party surrounded the store, believing it garrisoned with proslavery men. Ruffians in the band looted nearby stores. The Free Staters broke into the store, and Montgomery stopped the looting. The Free Stateman was released.

J. E. Jones started the Fort Scott Democrat newspaper in the winter of 1857-1858.

On January 1, 1858, William T. Campbell, who had just moved to Fort Scott from Barnesville, succeeded C. Dimon as proprietor of the “Free State Hotel,” and on the 18th gave an “opening ball.” One fiddle furnished the music, and Joseph Ray did the calling to the eminent satisfaction of all, except one Pro-slavery young lady, who said she “didn’t like that darned Abolition prompting.”

Across the Plaza to the southwest, in early 1858, Mr. McKay opened the Western Hotel, which immediately became the Pro-slavery headquarters and was henceforward known as the “Pro-slavery Hotel.” That year, another school was opened in the old government hospital building.

During the early part of the winter, Alexander McDonald, E. S. Bowen, and A. R. Allison arrived. On January 6, 1859, McDonald and Bowen selected a site at the foot of Locust Street for a sawmill they had purchased in St. Louis. In the early spring, the mill was erected, and it sawed all the lumber for the town company’s building and some frame dwelling buildings. In the fall, a corn cracker was added to the mill. The First Presbyterian Church, established in 1859, was the first religious organization in the town. St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church was partially organized the same year.

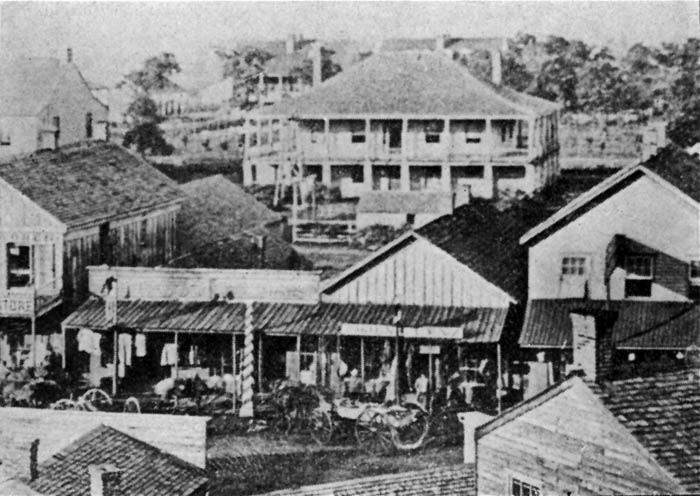

Fort Scott, Kansas, in the 1860s.

The years 1859 and 1860 were, for the most part, peaceful and devoted to material interests and the building up of the town.

Up to 1860, the school population of the city was about 300. The town was incorporated in February, and Colonel Judson was the first mayor elected under the charter. In the spring, two stores had been erected on Market Street — one by W. I. Linn, the other by J. S. Caulkins, the store of the former being the first frame building erected in the city outside the Plaza. In the fall, the first frame dwelling house was erected by “Uncle Billy” Smith on the corner of Locust Street and Scott Avenue. At about the same time, a second blacksmith shop was started by O. H. Kelley, and “Fort Roach” was built at the corner of Jones and Hickory Streets. It was a small log structure and often served as headquarters for the “Jayhawkers” on the occasion of their numerous raids into the city. George J. Clark and William Gallaher erected a small log building and B. P. McDonald and A. Campbell, a small house on Main Street. The Catholic church was established that year.

The Tri-Weekly Stage ran between Kansas City and Fort Scott in the 1860s. The fare between the two points was $10 and “carry a rail,” the term of the day for walking alongside the stagecoach when the roads were terrible. When the roads were good, a male passenger only had to carry a rail about a third of the way. But it was worth the price to ride into the Wilder House with a grand flourish.

The town company obtained title to its land on September 17, 1860. The townsite initially consisted of 320 acres, but the company later purchased an additional 200 acres. Dealing liberally with the old settlers, the company donated to them the lots upon which the houses purchased from the Government stood. They also donated lots to all the religious denominations, to the Government for a National Cemetery, and a square to the county for a courthouse and jail.

In the early winter, a sawmill was erected at the foot of Locust Street, where lumber was sawed for the town company’s building and several frame dwellings.

On April 24, 1861, a Union demonstration was made at Fort Scott, and local differences were lost sight of in the face of the great issue. At the outbreak of the Civil War that month, many of the loyal citizens enlisted for the defense of the Union, and Fort Scott would gain a long roll of honor for those who lost their lives in defense of the country. Fort Scott again assumed importance as a military post, storing ample supplies for troops as far south as the Red River. Several forts were built in the town, including Fort Henning, at the corner of First Street and Scott Avenue; Fort Blair, at the corner of Second Street and National Avenue; and Fort Insley, north of the plaza. At one time, there were 2,000 troops stationed in the town, and while it was menaced, no Confederate force ever reached it.

Fort Scott was a U.S. Army district Headquarters, quartermaster supply depot, training center, and recruitment station during the Civil War. It was strategically vital to the defense of Kansas and the Midwest. A battle over the fort occurred in August 1861, just across the Missouri line, in the Battle of Dry Wood Creek. The battle was a Confederate victory for Sterling Price and his Missouri State Guard. However, Price did not hold the fort and continued a northern push into Missouri to recapture the state. Senator James H. Lane was to launch a Jayhawker offensive behind Price from Fort Scott that led to the Sacking of Osceola.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis R. Lewell, commanding the Sixth Kansas Cavalry, was appointed Post Commander in 1862, and fortifications, consisting of breastworks, stockades, and three blockhouses, Fort Henning, Fort Insley, and Fort Blair, were erected. General James H. Lane, appointed Union commander for recruiting in the Department of Kansas in July 1862, also established his headquarters at the fort. Fort Scott was noted for its gaiety during the 1860s and 1870s. Even during the tense days before the war, the Free State Hotel was as gay a spot as was to be found in southeastern Kansas. According to early newspaper accounts, the “elite of the town” gathered and frequently “danced and joshed each other until seven o’clock in the morning.”

The Western Volunteer newspaper was started in 1862. Within a few months, it was enlarged and named the Fort Scott Bulletin.

Early in its history, Fort Scott became recognized as a manufacturing center. J. A. Bryant established the Pioneer Wagon Manufactory in 1862. By the early 1880s, this establishment was manufacturing the “Bryant” wagon and enjoyed a large and prosperous business.

In 1863, school attendance was 248, and in 1864, it was only 210. Before 1863, the city was without any regular buildings for school purposes. Seeing the necessity of the matter, the ladies took steps toward some improvement in this direction. Accordingly, a petition signed by Mrs. Jane Smith and 33 other ladies was laid before the City Council, asking them to take steps toward erecting a suitable school building. The matter was referred to a committee, which reported that the city had no jurisdiction and was consequently dropped.

In the summer of 1863, a City Hall was built, which served as a hall, church, school purposes, etc. In 1869, the school board purchased Block 158 and erected the Central School Building the following year. The large three-story brick building contained 12 rooms and cost about $60,000.

Little progress was made in the city during the Civil War. However, afterward, it made steady and sure progress and was justly called the “Metropolis of Southeastern Kansas.”

After the war’s end in 1865, the remains of those buried in the old military cemetery and other soldiers buried in the vicinity, in Missouri and Kansas, were re-interred at Fort Scott National Cemetery, which the Government had established on November 15, 1862. Following the close of the Indian Wars and the resettlement of Native Americans, the Army closed or consolidated many of its small military outposts in the West. As a result, between 1885 and 1907, the federal government vacated numerous military post cemeteries, such as Fort Lincoln, Kansas, and re-interred the remains at Fort Scott National Cemetery. Fort Scott National Cemetery sits two miles southeast of historic Fort Scott.

The Fort Scott Brewery was started in 1865 by A. Butler in manufacturing beer. The same year, a permanent school building was erected, which served the three-fold purpose of the schoolhouse, church, and city hall.

The Wilder House, just off the Plaza on Main Street, replaced the Free State Hotel as a rendezvous in the late 1860s. Famed in the vicinity was the reply of the hotel keeper when new arrivals asked, “Is this the Wilder House?” “You stay here awhile,” he would drawl, “and you’ll find there ain’t a wilder house in the country.”

The school population of the city in 1869 was 520. A school was established for the colored children, and the hospital building was purchased and fitted out. The Freedman’s Home Mission sent a missionary to take charge. The school now comprises four departments. The last school census shows the school population of the city to be 2,300, the enrollment to be 1,500, and the average attendance to be 1,100.

The City Brewery was established in 1869 by F. Schultz and C. Smith. It started on a small scale and gradually enlarged to a capacity of 5,000 barrels of beer per year.

The Fort Scott Foundry and Machine Shops, owned by George A. Crawford, began operations in the fall of 1869. By the early 1880s, it employed about 100 men to manufacture boilers, engines, and improved machinery.

The same year, the first railroad to reach Fort Scott was the Missouri River, Fort Scott & Gulf Railroad, which was completed to the city in December.

In 1870, the central school building containing 12 rooms was erected for $60,000.

The First National Bank was organized on January 10, 1871, with a capital stock of $50,000.

The Excelsior Mills, for the manufacture of flour, was started in June 1871 by E. A. Deland and F. C. Bacon. Before the end of 1871, a large mill was completed at a cost of about $40,000. The main building was three and a half stories high and had an engine house. The machinery was of the most approved patterns, complete in every detail, and was run by a 40-horse power engine. The mill could manufacture about 300 barrels of flour daily, for which a market is found in Kansas, Texas, Colorado, and other areas.

The same year, the Fort Scott Gas Works were built and completed on October 8 at a cost of about $45,000. The works were initially made from 10,000 to 15,000 feet of gas daily.

In 1872, the “East Side” school building was erected for about $12,000. Subsequently, it was destroyed by fire and replaced in 1880 by a two-story brick schoolhouse containing four rooms erected for $6,000.

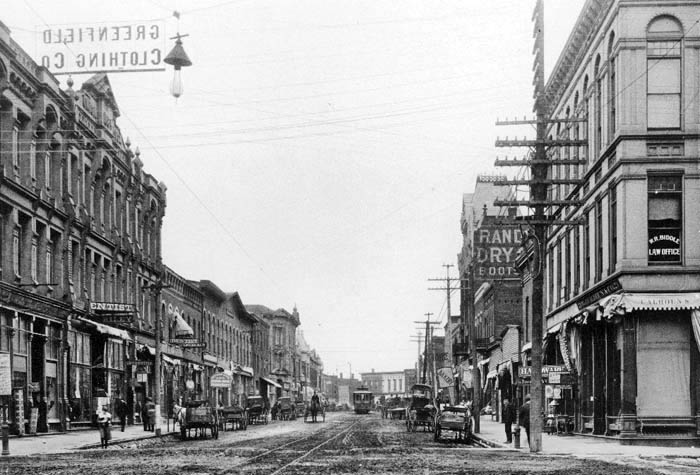

Fort Scott, Kansas Main Street, about 1875.

The Goodlander Flouring Mill, built by C. W. Goodlander the same year, had a capacity of 125 barrels per day. Unfortunately, an explosion occurred in January 1876, and the mill then passed into the possession of the First National Bank. By 1880, it was operating again.

The Fort Scott Woolen Mill was established in the spring of 1873 by A. Polsgrove & Son. The object of the mills was the manufacture of hosiery. At first, it was begun in a small way, and during the first year, only 25 pairs of hose were made. The mills were then enlarged, and before long, the operation manufactured 4,000 dozen pairs of hose. At first, only one knitting machine was employed, but that grew to 14. A combination of steam and windmill power ran the mill. Later, the operation was enlarged to include a one-story stone building 87 feet long by 36 feet wide, with an engine house, knitting apartments, and other outbuildings. Before long, production increased to about 20 dozen pairs of hose per day, requiring a force of 22 employees.

The Castor Oil Mill was begun by H. Mahew & Son in 1873. A horsepower press was used, and the mill manufactured about 80 gallons of castor oil per day, for which a market is found in Kansas City, St. Louis, and Texas.

A Planing Mill was started in the fall of 1876 by S. S. Peterson and J. H. Gardner. It began as a sash and door factory, and the light machinery used was run by tread power. As the business gradually increased, other machinery was added, and horsepower was employed. In 1880, a four-horse power engine was procured, and in about 18 months following, a ten-horse power engine was put in. Several machines are employed, and all sorts of job woodwork is done. The principal business is the manufacture of sash, doors, blinds, stair railings, and moldings. About 10,000 feet of lumber is consumed monthly, and employment is given to a force of eight men.

The Kansas Normal College was established at Fort Scott in 1878 by Professor I. C. Scott and Professor D. E. Sanders. The institution’s design was to meet the wants of students who desired practical preparation for the demands of life in the shortest time and at the least possible expense. The school was first kept in the Congregational Church and consisted of about 60 students under the instruction of two teachers.

In 1880, Kansas voters approved an amendment to the Kansas Constitution prohibiting all manufacture and sale of “intoxicating liquors.” At that time, C. Herring used a part of the Fort Scott Brewery to manufacture soda and mineral waters and soon made about 300 gallons of these waters per day. Unfortunately, the City Brewery failed at that time.

John E. Petty started the Foundry and Sickle Factory with one assistant in 1880. It manufactured plows, sickles, grinders, harrows, scrapers, spring wagons, cultivators, shovels, single-trees, neck yokes, and shovel plows. The company initially employed 16 men but increased dramatically in the following years.

A two-story brick college building was erected for the Kansas Normal College in 1880 for about $6,000. The building contained seven large recitation rooms and other rooms necessary for learning institutions. Contributions were received from the citizens of Fort Scott toward the erection of the building. A two-story frame boarding hall was built to accommodate students the following year. The terms were exceedingly low and easy, thus placing the advantages within reach of persons of limited means. Among the attendees were students of both sexes from various States and Territories.

D. W. and R. L. Milligan started the Acorn Flour Mills in January 1882. The mill building was a two-story frame. Four runs of stone were employed, with a capacity for grinding 150 bushels of wheat and 200 bushels of corn per day. The machinery of the mill was run by a 40-horsepower engine.

The Fort Scott Water Company was organized and incorporated on June 5, 1882. The system operated on the gravity principle using an elevated reservoir and tower. The earth reservoir, with a storage capacity of two million gallons of water, was constructed about 75 feet above the city. The pumping house was stone masonry with a brick smokestack 50 feet high. A residence near the reservoir was constructed for the engineer.

Cohn’s Restaurant and Confectionery on East Wall Street became the town’s social hub in the 1880s. One local newspaper called it “The Delmonico of the West. ” It was “a royal restaurant with dining parlors handsomely painted and papered in the highest style of art, the popular and stylish resort of the city… ” Elaborate dishes included “Quail a la Marmaton” and “Turkey a la Pawnee.”

Fort Scott, Kansas, in about 1890.

Fort Scott’s population peaked in 1890 at 11,946.

The Fort Scott Normal School closed in 1899.

By the beginning of the 20th century, social life was greatly subdued. The town was developing as a manufacturing and trading center. Then, in the early 1900s came a slump in business activity, a gradual letdown after a half-century of bustling activity. For years, farmers in the vicinity produced grains and vegetables with only moderate success.

In 1909, the city had 36 manufacturing establishments, the capital invested being $626,000 and the net value of the products being $340,000. Natural gas, waterworks, and lighting systems, and an electric street railway lit and heated the city.

In 1910, a survey was made. Fort Scott businessmen offered to promote the establishment of ice cream factories and creameries if the farmers would devote their resources to raising dairy cattle. Local banks extended credit to farmers who bought dairy cows and marketed their milk in Fort Scott. Progress was slow initially, for money was scarce, and a limited market retarded production. At that time, abundant building stone, lime, cement, coal, water, and natural gas existed. At that time, its population was 10,463.

In 1918, the Borden Company erected a condensery, furnishing a year-round market that ensured the success of the dairying program.

Fort Scott Community College was established in 1919. The first graduating class in 1921 had two members. Originally, Fort Scott Junior College shared the Fort Scott High School building and operated as an extension of the high school program for students in the 13th and 14th years of public education. It is the oldest public community college in Kansas today.

In 1938, 30 milk trucks covered the territory, carrying approximately 150,000 pounds of milk daily into Fort Scott. Farmers received almost $ 1,000,000 yearly for dairy products, the more significant portion of which was spent in this vicinity or deposited in local banks. Dairymen and businessmen promoted a Dairy Show annually. In addition to the dairy industry, Fort Scott had two railroad shops, an overall factory, a monument factory, foundries, and paving brick plants. A hydraulic cement plant just north of town was among the largest in the Middle West, and coal deposits, which accompany the cement rock deposits, furnish fuel for the plant’s operation. The mining of coal is an industry of steadily increasing importance in the area.

By 1939, Fort Scott boasted eight hotels, five tourist camps, and several boarding houses. It also had three motion picture theaters, segregated swimming pools, and several parks. At that time, it was described as “a city of jogging” streets and fine old trees, with buildings older than Kansas itself sandwiched between modern structures. At the junction of three railroads, the city was also a significant distribution and shipping point and a manufacturing center in southeastern Kansas.

Fort Scott continued to be an agricultural and small industrial center in the following decades, though its population gradually decreased.

On March 11, 2005, a fire destroyed several historic buildings in Fort Scott’s downtown. The Victorian-era buildings are among many that symbolize the town.

Today, the city has a total area of 5.59 square miles, of which 5.55 square miles is land and 0.04 square miles is water.

Fort Scott Community College, founded in 1919 and the oldest community college in the state of Kansas, continues to serve it.

The Fort Scott USD 234 public school district serves primary and secondary education. It includes two public elementary schools, one public middle school, and the Fort Scott High School. There is also a Catholic school for grades K–5, Fort Scott Christian Heights for grades K–12, and a few other small private schools for students from grades K–12. There is also a public preschool in the old middle school building.

The community provides several museums, including the Fort Scott National Historic Site, featuring its historic fort and its history, including the Indian frontier, through Bleeding Kansas, The Civil War, and the Railroad Expansion. The city also provides narrated Trolley Tours featuring the National Cemetery’s beautiful homes, mansions, landmarks, and more. A Historic Downtown Fort Scott Walking Tour is also available. Lake Fort Scott is located just a few miles southwest of Fort Scott, Kansas, providing fishing, recreational boating, and camping.

Fort Scott is located at U.S. Routes 54 and 69 intersection in southeast Kansas, approximately 54 miles north of Joplin, Missouri, 92 miles south of Kansas City, and 143 miles east of Wichita.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Fort Scott National Historic Site

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Federal Writer’s Project; Kansas, A Guide to the Sunflower State, Viking Press, New York, 1939.

Wikipedia