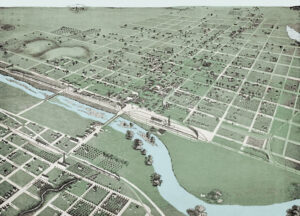

Kingman, Kansas, is the county seat of Kingman County on the Ninnescah River. Located north of the central part of the county, it is the largest city in Kingman County, with a population of 3,105 people per the 2020 census.

When the county was organized in 1874, both the city and the county were named for Samuel A. Kingman, a Supreme Court chief justice.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 3.53 square miles, of which 3.52 square miles is land and 0.01 square miles is water.

As early as 1872, a party from Hutchinson, Kansas, organized a town company and located a town called Sherman on what is now the townsite of Kingman. However, when they found out they could not get a deed on the land, they abandoned it. Afterward, brothers J.K. and F. S. Fical pre-empted the land in 1873.

Jesse McCarty surveyed and platted the townsite in March 1874 on the north side of the Ninnescah River. Afterward, the Fical brothers conveyed a half interest in it to J.M. Jordan. In 1874, building on the townsite began, with H.L. Ball putting up the first building, which he named the “Kingman House,” that served as a hotel. A small frame schoolhouse was erected that year on the corner of D and Main Streets, and the county officers occupied a small frame building. A small frame residence was built in 1874 by A.D. Culver, and a little frame store was built by E.C. Manning, the first person in the town to start a small mercantile business. Soon, Manning’s store passed into C.C. Barnard’s possession.

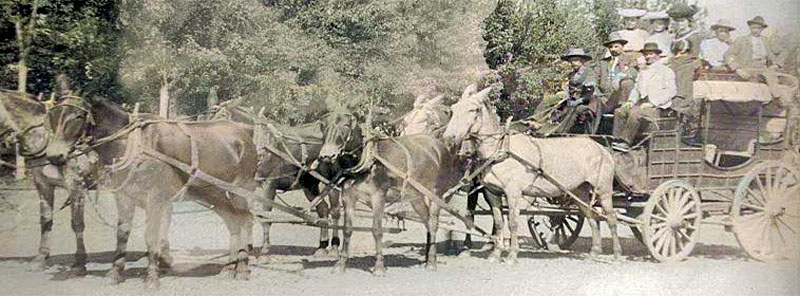

The Cannonball Stage Line began service in 1876. It ran a team of horses, stopping every 15 miles to change horses, through Pratt to Coldwater and later to Greensburg. The stage road of the old Cannonball Express in Kingman was along the route of present-day Highway 54

The first attorney was George E. Filley, who came in 1877. That year, the last buffalo in the county was killed.

The town did not grow in its initial years, and no further improvement occurred until 1878. That year was prosperous for Kingman, and many new settlers settled there. In the spring, a party from Hutchinson organized itself into the Kingman Town Company. Previously, the original townsite, laid out by the Ficals in 1874 on the north side of the river, had passed into the hands of a company. The new company’s objective was to locate the town on the high ground south of the river, which, in its growth, would absorb the older town. The new town rapidly progressed for the first year, and several buildings were moved from the north side. The town company erected a good-frame hotel, the Laclede House, and several residences were also built.

The north town was not idle while the south town was pushing on its improvements. In the former, a grocery store was put up by Newton Perch, a lumber yard was opened by Frank Leach, who also built a neat residence, store buildings were put up by S. Turner, C.W. Myers, and Livingston & Reynolds, and a bakery was established by F. Tull. Several dwelling houses were also erected. The following year was also prosperous and progressive for Kingman, especially in the old town. Business houses were put up by Chamberlain & Glunt, L.C. Almond, and A.L. Garrison.

The town started on the south side of the river and reached its glory at about the end of the first year of its existence. It was discovered that well water was almost, if not quite, inaccessible; those who had located on the south side began to move over to the north side, where the finest water could be had with but little difficulty, and all that was left on the south side was the old “Poland Hotel” which had been converted into a grocery store.

In 1880, the town was improved by erecting three store buildings and several dwellings. One of the stores was a building that had been commenced sometime before by the county for a courthouse. After putting up the foundation and part of the walls, they discontinued work and sold it to Babcock & Craycraft, who finished the stone building and converted it into a hardware store.

On March 10, 1881, Gassard Brothers and H. L. Strohm established a private bank. Subsequently, the bank passed into the hands of a company under whose management it was incorporated on February 25, 1882. The bank officers were L.C. Almond, President, and John P. Jones, Cashier. Its resources on December 30, 1882, were $30,454.19. That year, the Laclede House, standing on the south side of the river in 1878, was torn down, moved to the north side, rebuilt, and greatly enlarged. A hardware store was also built and opened by Karr & Lewis, and E.W. Hinton established a drug store.

A fine stone schoolhouse measuring 32 by 60 feet was completed in early 1883. It contained two large rooms, which, with the old frame building, was used as a primary school that provided ample school accommodation for the town’s children. As early as April 1 of that year, two new stores had been built, and Dr. E. W. Myers built a new post office building. Ten new dwellings were in the course of construction, and two blacksmith shops and a wagon shop had been completed. Though the town had no church buildings, the Methodists, United Brethren, Presbyterians, and Baptists had organized and regularly held services. In April 1883, the Methodists prepared to build and had the material hauled on the ground. The congregation had formerly met at the schoolhouse.

At that time, the town had a population of about 350. Its businesses included four general merchandising stores, two hardware stores, two groceries, two drug stores, two millinery establishments, a furniture store, a jewelry store, a bank, two hotels, a restaurant, a harness and saddlery, a lumber yard, three livery stables, and two newspapers. The legal and medical professions were well represented, and several benevolent societies existed.

Grading began from Wichita to Kingman in August 1883 to build a branch of the Wichita and Western Railroad. When the track finally reached Kingman on June 6, 1884, everyone in the city turned out to greet the first railroad to come to town.

The importance of the railroad’s arrival to Kingman’s citizens was not understated in the Kingman Courier:

“During Kingman’s brief existence as a city, she knew a few days of general rejoicing, as she had last Monday. For two weeks past, the current topic of conversation was the advent of the railroad. As it advanced mile after mile up the valley, the excitement heightened and increased until last Sunday, the workmen came within hailing distance of the corporate limits, and the greater part of the population turned out to witness the process of construction. The old and young, the pious and the ungodly, all went out to the deep cut just east of town where the men were at work, totally oblivious to the sanctity of the blessed Sabbath. Of the crowd of four or five hundred that assembled to witness the work, none were so pious as to condemn it — all were ready to recognize it as a matter of extreme necessity.

Monday morning, work was resumed, and by ten o’clock, the track had reached the city limits. During the afternoon, the crowd of spectators increased. By the time the laying, leveling, and spiking had reached Main Street, nearly one thousand people crowded around to see the first engine pass across the city’s principal thoroughfare. The Kingman Cornet Band was out discoursing enlivening music, and the spikes sank into the ties to the measure of the sweet strains. Engine No. 90 was the first to make the crossing… and there was scarcely a male hat that was not swung in the air. The citizens were so grateful to the railroad employees that the town had prepared a supper for the nearly two hundred employees.”

— Kingman Courier, June 1884

Passenger trains began running the next week, and almost as quickly, the train became a fixture in Kingman’s social and economic life.

With the arrival of the track into Kingman in 1884 came the town’s first depot building. As with most communities just entering the era of railroad transportation, it was a typical wooden building that was quickly erected.

With the trains came new settlers, and the freight goods needed for the new residents began arriving nearly as quickly as passengers. Lumber cars were consigned for new houses in town, and Kingman’s economy soon depended upon the railroad.

The Missouri Pacific Railroad arrived in Kingman in 1887. Afterward, the Cannonball Express ceased to exist. Pure rock salt was discovered nearby that year, and evaporation plants were soon built. Additions to Kingman were hastily platted, and workers moved to town. As Kingman grew, additional lines were necessary. Trackage was laid to Pratt by 1887.

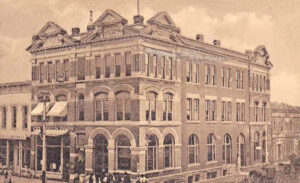

In 1887-88, the three-story First National Bank was built at A and Main Streets. The first officers were R.W. Hodgson, president, and David B. Cook, cashier. It would continue business for nearly 50 years.

By 1888, Kingman needed a city building. In a special election on February 13, 1888, a 63-vote majority approved the $10,000 project. The following month, the city council considered the six bids submitted for construction and unanimously accepted the highest bid submitted by John A. Cragun of the Kingman National Bank. In late May, quarrying of white limestone began two miles east of the city. The cornerstone ceremony was held on June 23, and the building was completed on C and Main Streets in December. The two-story brick and stone structure housed the city offices, jail, and fire department. The front tower originally housed a bell used for special occasions and fires. The second tower was used to dry fire hoses after use. In the following years, the city building was used for elementary and high school classes, and the city library, lodge hall, city police department, and apartment for the fire engine driver were housed.

The Wichita and Western Railroad was consolidated in 1889, becoming the Kingman Pratt and Western Railway. After the Kingman Pratt and Western Railway went bankrupt, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad acquired the line on December 31, 1898. By this time, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad not only managed to stay financially solvent after the grasshopper plague and the droughts of the 1870s but flourished in Kansas, eventually becoming the state’s largest company. Part of its growth was due to consolidating other smaller Kansas lines. As one of the better-managed railroad companies in Kansas, the railroad company stayed profitable for many years when other companies failed.

In 1899, Kingman’s boom turned to bust when Oklahoma land was opened to the public.

The Kingman County Courthouse at 130 Spruce Street was built in 1907-08. The historic three-story red brick courthouse is set on a ground-floor basement of rough-faced white limestone. The stairway and entrance portico leading to the main entrance are the same limestone. Its hipped roof has gables in the middle of each side, pyramids on each corner, and an octagonal-shaped cupola rising from the center. It was designed by architect George P. Washburn of Ottawa, Kansas, in a mixture of Late Victorian, Romanesque, and Queen Anne architectural styles.

In 1910, Kingman had two lines of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad and the Missouri Pacific Railroad. Described as “a fine little business city with good buildings and well-kept streets,” there were three banks with a total capitalization of $125,000, a new courthouse, one of the largest flour mills in southwest Kansas, which had a capacity of 600 barrels of flour per day and a storage capacity of 170,000 bushels of wheat, two grain elevators, two schools, four churches, an ice plant, a creamery, an ice cream factory with a daily capacity of 400 gallons, three hotels, 15 miles of water mains, several business houses, an electric light plant, a sewer system, a fire department, a carpet factory, cereal mill, and an opera house. The water supply came from natural springs of unusual purity. A salt mine that produced crystal rock salt operated two miles away.

The town’s principal shipments were salt, livestock, grain, flour, and produce. Two newspapers, the Courier and the Journal, were published weekly. At that time, the town also had telegraph and express offices, an international money order post office with four rural routes, and a population of 2,570.

Like most communities in Kansas, the citizens of Kingman were not satisfied with the first frame depot that was constructed when the railroad first came to town. The condition of the wood depot, the importance of a depot building to Kingman, and the need for a better depot were all voiced in these words from the Leader-Courier in 1910 in anticipation of the construction of a new depot building by the Santa Fe Railroad:

“There has not been a time in the past twenty years when the depot facilities at Kingman were adequate to meet business demands. The erection of the new passenger depot will fill a long-felt want and will, at the same time, naturally create a more cordial feeling between Santa Fe and its patrons… A poorly equipped, small depot with dilapidated surroundings naturally creates a bad impression… The new depot will be modern in terms of appointment and appearance.

The new depot will be 32 x 119 feet, with a platform all around the same, 180 feet in length, to connect with the present platform… A brick walk will be 8 feet wide and 470 long, bordered by a brick curbing on a concrete base to connect with city pavement… At one end of the building, there will be a summer waiting room 20 x 23 feet, with a double row of concrete seats across the center and a single row against the outer wall. Adjoining this open room will be a ladies’ waiting room 23 x 24, with a corridor between the office and lavatories, leading to the men’s waiting room, which is to be the same size as the ladies’ room. The office will occupy a space 14 x 14 in the center of the building, facing the track with the ticket window opening into the corridor. Across from the office will be the toilets, equipped with the very best grade of plumbing fixtures… There will be separate rooms for baggage and express at one end of the building of ample size to make handling the baggage and express convenient. The furniture will be finished in fumed oak and of a design such as used in all first-class stations on the Santa Fe.”

Despite the thorough description of the anticipated building, after its construction, the citizens were less concerned with the details than they were with the final results, especially in comparison to the former depot: It was enough that there were two waiting rooms and an outside covered waiting room with concrete seats, where overflow crowds at summer excursions could find room. The building was heated with steam, and improved electric lights replaced the dim, murky gloom of the previous depot.

The new Kingman Santa Fe Depot was constructed during a period of financial strength for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway Company. The brick depot cost $13,480.98. The surrounding station land was also upgraded during its construction. The depot was not only the center of everyday activities essential to the functioning of the town and surrounding agricultural community, but it was also the location of many special activities throughout the years. Special trains brought people from Pratt and Wichita during the Kingman’s annual Cattlemen’s Picnic. The high school also used the trains to go to sporting events.

After the new depot was built, the old wooden building was moved and used as a freight depot.

Built in 1914, the Kingman Public Library is one of several Carnegie Libraries on the National Register of Historic Places.

The discovery of oil in 1926 made oil and natural gas the county’s primary source of income.

The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad was integral to Kingman’s economy until the advent of the automobile. Regular passenger trains were used on the Kingman Santa Fe line until the 1930s when running a mixed train was more economical. The company began cutting back after World War II, and passengers in the 1940s and early 1950s often used the Doodlebug, a self-contained track vehicle that hauled passengers, freight, and mail.

This first wooden Santa Fe depot was demolished in 1947.

In 1949, the Santa Fe Railway began hauling truck freight to keep competitive with changing modes of shipping. Steam-powered locomotion was common until March 1952, when the first diesel train crossed the line. The railroad abandoned unprofitable branch lines in the following years, reducing passenger and freight service.

The last passengers rode on the Kingman Santa Fe line in May 1967.

The city building was used for the original purposes until 1967 when the city planned to purchase new office quarters and vacate the old building. At that time, the Sinclair Oil Company secured an option to purchase it for $25,000, which was later reduced to $15,000. After razing the city building, the oil company intended to build a service station. However, community citizens objected, and town meetings were held to discuss the issue. Ultimately, the Kingman County Historical Society purchased the 80-year-old building in 1969. The Kingman County Historical Museum officially opened in 1970. Located at 400 North Main Street, the exhibits change regularly on the main floor, but the second floor displays permanent exhibits.

In January 1994, the Santa Fe line from Wichita to Pratt and from Kingman south and west was sold to OmniTrax of Denver, Colorado, the parent company of the Central Kansas Railway. The Central Kansas was a short-line railroad that ran trains on this track once or twice a week — more often during the summer wheat harvest. The Central Kansas Railroad used the depot for storage. Within a year after Central Kansas took possession of the depot, local citizens received permission to give the depot a cosmetic restoration.

In March 1999, a private citizen purchased the Santa Fe Depot from the Central Kansas Railway and later deeded it to The Santa Fe Depot Foundation, a non-profit organization. Watco Co. of Pittsburg, Kansas, which operates the railroad as the Kansas & Oklahoma Railroad, purchased the depot itself. The one-story Mission Revival-style depot building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.

Today, the depot houses the Cannonball Welcome Center for tourist information and a railroad museum. Small meetings, parties, reunions, and other events are sometimes held in and around the building.

Kingman is 44 miles west of Wichita via U.S. Route 400 at the junction of State Highway 14.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, April 2024.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Kingman County

Sources:

Abandoned Kansas

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

National Register Nomination – Santa Fe Depot

Nation Register Nomination – City Building

Numismatic News

Wikipedia