Missouri Bushwhackers.

Like many other Kansas counties, Morris County had its share of issues during Kansas’ fight to become a Free State, which continued into the Civil War.

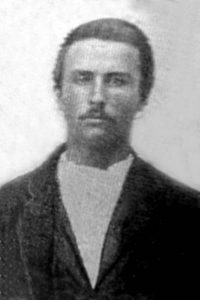

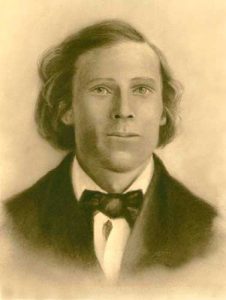

After the commencement of hostilities between the North and the South, the people of Morris County were kept in a constant state of feverish excitement by perpetual threatened invasion from hostile Indians on the south and west and by incursions of Missouri bushwhackers, who, after committing all manner of violence in the eastern portion of the state, were working to the mountains and plains of New Mexico and Colorado where they could prey upon trains crossing the plains, and murder all the defenseless people who favored the Union. During one of these bushwhacking raids in 1862, by Bill Anderson and his followers, Judge A.I. Baker, one of the most respected citizens of the county, and his brother-in-law, George Segur, were murdered at Baker’s home on Rock Creek.

The Anderson family lived in Kansas, near the Bakers, when the Civil War began. Natives of Missouri had moved to Kansas before it became a state, when it was thought that Kansas could be made a slave state by colonizing mainly from the South.

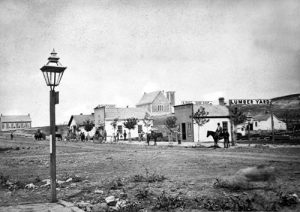

The neighborhood people looked upon the family as hard characters, and it was an open secret that they had committed several murders. To kill, steal, and plunder was their business, and they became quite a terror to the community. The breaking out of the Civil War opened them up to grand opportunities for carrying on their hellish business, which they were not slow to take advantage of. Several other desperate characters joined them, among them one Lee Griffin and a notorious scoundrel named Reed. They established their headquarters at Council Grove and, from this point, would sally out and commit all manner of depredations, including murder, rape, and horse-stealing. In one of these marauding excursions, they stole two horses from George Segur, father-in-law to Judge Baker.

On hearing of this, Baker, with several others, started in pursuit and overtook the party on the Santa Fe Trail, some distance west of Council Grove. The horses were recovered, and Baker swore out an arrest warrant against the Andersons. This came to the knowledge of old man Anderson, he swore he would take Baker’s life, and, arming himself with a rifle and with murderous intent, he went to Baker’s house. Having been informed of Anderson’s design, Baker met him prepared, and before the latter could carry out his murderous purpose, Baker shot him dead.

The following night, the young Andersons, with Griffin and Reed, went to Baker’s house, intent on killing him, and called him out, but Baker, apprehensive that something of the kind would occur, had secured a friend or two to stay with him, and when he made his appearance, it was with his friends. Finding themselves thwarted in their purpose to kill Baker that night, the Andersons retired to the brush where they lay concealed, watching for an opportunity to dispatch their victim. After waiting for a week or two without finding the opportunity they sought, they departed for Missouri.

More than a month passed by without anything being heard of the Andersons and their gang, and a faint hope began to be entertained that they had seen the last of them in the neighborhood when, on the morning of July 2, 1862, the Andersons were discovered skulking in the vicinity of Baker’s house. They had returned the previous evening, and with them was another villain, a stranger unknown to anyone in the community. Learning of Baker’s absence from home, the Anderson gang secreted themselves in the neighborhood, leaving the stranger to watch Baker’s house and apprise them of his return. On the evening of July 3, Baker returned from Emporia, which the stranger immediately communicated to the Andersons.

At that time, Baker kept a supply store near the Santa Fe Trail, about seven or eight rods from his house. The Andersons were not long in perfecting their plans. The stranger was sent to Baker’s house, instructed to tell him that he was the “boss” of a train camped a short way off and desired to purchase some supplies. Baker, never having seen the stranger before, and this being a usual occurrence, was entirely free from suspicion. However, in those unsettled times when every man on the frontier went armed, he took the precaution to buckle on a pair of revolvers, and accompanied by his brother-in-law, George Segur, he went with the stranger to the store. It was now well into the evening, so the Andersons could station themselves close to the store without running much risk of detection under darkness.

Baker had just about finished putting up the stranger’s order when the Andersons, with their partners in crime, rushed into the store and fired, wounding both Baker and Segur in the first discharge. Taken by surprise and being outnumbered two to one, Baker and Segur, in their wounded condition, sought shelter in the cellar, where the murderers sought to follow them, but Baker, firing through the cellar door, wounded Jim Anderson in the leg, breaking his thigh bone. The Andersons then withdrew from the building and set fire to it. In the cellar, Baker told his brother-in-law that he was mortally wounded and could not live long and advised Segur to escape through the cellar window, which, after much difficulty, he succeeded in doing. While flames were devouring the store, the desperadoes watched outside lest Baker should escape, as one of the most respected citizens of Morris County was burned to death in the cellar of his store by this gang of cutthroats. Segur died from his wound on the following day. After finishing their hellish work in Morris County, the murderous gang returned to Missouri, continuing their guerrilla warfare and bushwhacking.

Although Colonel S.N. Wood had, by the authority of the Secretary of War and the Governor of Kansas, organized the Morris County Rangers in the early part of 1863, guerrillas were not deterred from making plundering and murderous incursions into the country. On May 4, 1863, Dick Yeager and his band of guerrillas encamped in the vicinity of Council Grove. No doubt he intended to sack the town, but the people armed themselves and posted sentinels each night, frustrating his plans. After domineering over the citizens for some time with a high hand and using threats and insults, he withdrew with a portion of his band to Diamond Springs, where, without either ceremony or provocation, they shot and killed a citizen named Augustus Howell and severely wounded his wife.

Another thing that tended to save Council Grove and its people from Yeager’s ravages was that Captain Rowell, with the company of the Second Colorado Regiment, was stationed close to the town to guard the mail and Santa Fe wagon trains. Throughout 1864, the people were kept constantly on the alert. Now, it would be a guerrilla raid that would call them to arms, and now a visit from hostile Indians. Many were the depredations committed that year by marauding bands of both whites and Indians. Still, knowing the insecurity of life and property in those harassing years, the people were always on the alert. While the depredations perpetrated in the adjoining counties were quite serious, Morris County escaped with a few minor incidents.

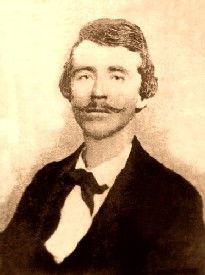

In 1867, the lynching of one of the guerrillas occurred, and the affair caused a great deal of excitement in Council Grove. In the fall of 1866, a man named McDowell came from Missouri and made Council Grove his stopping place. During the Civil War, McDowell had been a bushwhacker, and he became an outlaw when the war was over. He boasted of his crimes and seemed to take pride in telling how many men he had killed. People paid little heed to his boasting then and dismissed it as mere braggadocio. At that time, one W.K. Pollard kept a livery stable in Council Grove, and one day, McDowell went to the stable and hired a team, ostensibly to go to Junction City. When McDowell didn’t return, Pollard became suspicious and started after him the following day. On reaching Junction City, he found that McDowell had gone farther and was, by that time, probably out of the state. His next step was to procure a requisition from Governor Crawford. He started pursuing the thief and succeeded in overtaking him at Nebraska City, where he arrested him and brought him back to Council Grove. He had a preliminary examination and was held for trial at the District Court.

While McDowell was in jail, he was visited by a Shawnee County Deputy Sheriff named Cunningham, who attempted to smuggle him a gun. However, Cunningham was detected in the act, and before McDowell had an opportunity to use the gun, it was taken from him. When word got out about what Cunningham had done, a group of resolute men threatened to hang him. As Cunningham pleaded for his life, a rope was prepared, but in the end, the vigilantes let him go, and Cunningham left town, never to be seen again.

McDowell, however, would not be so lucky. The men then seized McDowell from the jail and carried him to the center of the bridge that crossed the Neosho River. McDowell begged and pleaded and screamed for mercy, but all his pleading fell upon deaf ears, for he was about to taste of that kind of mercy that he, by his boasting, had shown to his helpless victims when they appealed to him. One end of the rope was fastened around his neck, and the other end was secured to the bridge’s railing. Up he was lifted, and over he was dropped, and there he was left dangling until the next morning. An inquest held on his body rendered a verdict of death by strangulation.

A few days after this occurred, the whole community was thrown into considerable excitement by a rumor that members of William Quantrill’s and Bill Anderson’s bands, to which McDowell had belonged, were on their way to take revenge upon the people of Morris County, and Council Grove in particular. However, luckily for the people of Council Grove, it was a mere rumor.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated September 2025.

About this article: The primary content is from William G. Cutler’s History of the State of Kansas, first published in 1883 by A.T. Andreas, Chicago, Illinois. Note that the article is not verbatim, as corrections and editing have occurred.

Also See: