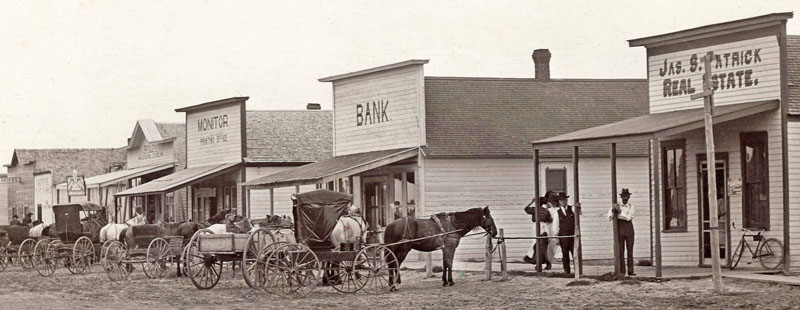

Santa Fe, Kansas, Main Street.

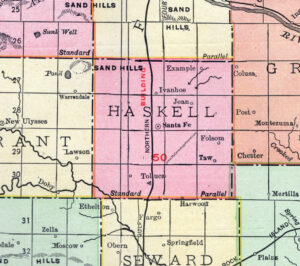

Santa Fe, Kansas, an extinct town in Haskell County, was the county seat for 26 years. The town is gone today; only the cemetery remains.

Before Kansas became a state, the only traffic in western Kansas was Native Americans, soldiers, and those traveling the Santa Fe Trail. However, after the Civil War, with the passage of the Homestead Act, residents of the East began migrating westward in search of free land.

On June 4, 1985, Star City was platted in Finney County at a site just east of the location where Santa Fe was later established.

In 1886, another company, of which J.A. Grayson of Chicago, Illinois, was president, bought the townsite and renamed it Santa Fe for the Santa Fe Trail that crossed the county just about five miles to the north. At that time, there was only one building on the townsite, which was likely the Lee and Reynolds stagecoach station serving Garden City, Fargo Springs, and Springfield in Seward County. Railroads had not yet reached the area.

Because the nearest water source was located in Ivanhoe, six miles north, a well was dug by hand to a depth of 220 feet, and then drilled an additional 100 feet. The settlers, for many miles around, came to the pump with their wagons and water barrels, sometimes lining up for an eighth of a mile.

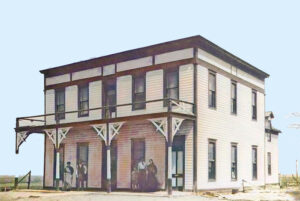

The townsite was surveyed, and the first lot was purchased by James S. Patrick, a well-known real estate dealer and abstractor who lived in Santa Fe. He built a store in the front yard of his ranch in Santa Fe.

On June 11, 1886, the first issue of the Santa Fe Trail described the new town of Santa Fe:

“The fact that a new town in south-central Finney County has been organized and is already assuming the appearance of a city is not generally known; nevertheless, such is the case. Santa Fe was started a few weeks ago, but its actual building boom did not set in until last week. Last Monday, three of four building companies commenced operations, and the fruit of their work today is evident in the neat, well-sized store buildings in Santa Fe. There are, at present, two grocery stores, one restaurant and hotel, one bakery, one laundry, and two lumber yards, and arrangements for businesses of all kinds have been made. They will be commenced as soon as the shelving and counters can be put in place for the reception of goods.”

The new townsite was platted on June 12, 1886, and officially recorded on July 31, 1886. When the town was established, the Indians had only recently been driven out of the area, and buffalo were still quite numerous. Herds of wild horses were seen in the area as late as 1883.

A post office was established on June 16, 1886, with James H. Grayson as the first postmaster.

Haskell County and Santa Fe grew rapidly in 1886, and in 1887, the boom continued, reaching a population of up to 1,200. At that time, numerous covered wagons traveled through the area. Town officials built a six-foot-wide boardwalk that extended three blocks in each direction from the town center.

On March 23, 1887, Haskell County was created, and Santa Fe was then at the center of the new county. Several months later, on July 1, 1887, Governor John Martin declared Haskell County organized and designated Santa Fe the temporary county seat.

The Santa Fe Monitor newspaper began publication on July 2, 1887.

On October 13, 1887, there was a contest between Ivanhoe and Santa Fe for the title of the permanent county seat. Santa Fe won the contest by a vote of 647 to 381.

On January 2, 1888, Santa Fe was incorporated as a third-class city. At about that time, the population of Santa Fe reached its peak at about 1,800. At that time, it had a school, three banks, two churches, two lumberyards, a restaurant, two grocery stores, a flour mill, the Rutledge Hotel, and a newspaper.

Hopes ran high when the Dodge City, Montezuma Railroad was begun around 1890. Haskell County citizens had voted in favor of bonds for this railroad. But gloom prevailed when the railroad reached Montezuma, and further construction was abandoned. Soon, the Texas and Southwestern Railroad surveyed a line from Garden City to Santa Fe. Citizens of Haskell County again voted for bonds for this project, which never extended farther than the banks of the Arkansas River one mile south of Garden City.

By 1891, the population of Haskell County and Santa Fe had fallen. Part of this was due to the 1889 opening of the Oklahoma Territory to settlement. In 1892, much of the wheat crop rotted in the stacks as it was too costly to thresh and haul it to market in Plains or Montezuma. Afterward, the farmers ceased growing wheat for many years, and many settlers moved to more prosperous regions. Remaining residents, however, clung to the hope of securing a railroad.

The excellent wheat crop of 1892 created quite a stir in Haskell County. That year, wheat yields reached as high as 40 bushels per acre, leading farmers and investors to become excited about the potential for profit. Many farmers incurred debt to purchase new farm machinery and expand their wheat acreage, encouraged by local bankers. In response to this optimism, bonds were issued and sold to finance the construction of a flour mill.

The mill relied on coal mined in Colorado or eastern Kansas, which was transported by rail to Garden City and then delivered by horse-drawn wagon to Santa Fe. However, the situation took a drastic turn for the worse. The abundant wheat crop of 1892 rotted in stacks because the costs of threshing and transporting it to market exceeded its market value. As a result, farmers fell deep into debt, leading to the collapse of the local bank, which held $12,000 in county funds. The county then took ownership of the bank building, which ultimately became the first courthouse.

The farmers of Haskell County had proven they could successfully grow wheat, but they struggled to afford to market it. Many believed that if only they had a railroad, the county could thrive as a prosperous wheat-producing area.

In 1893, during a drought year, when many people left, the remaining citizens tore up the sidewalks and used the wood to build windbreaks.

In 1896, the county population declined to 1,077, while Santa Fe dwindled to approximately 300 residents.

By 1899, the county population had reached a low of 434, and Santa Fe’s population had fallen to 60. Within a short time, empty houses were ransacked, and buildings were demolished or relocated. Of the several wells dug in the 1880s, all but one in front of the Court Brown Hotel had fallen into disuse as the exodus continued.

“When we arrived in Santa Fe in 1903, it was a rather desolate-looking town, no sidewalks, and the houses were unpainted and weather-beaten; the worst feature was that there was only one well.”

— Dr. Miner’s wife

On August 15, 1907, the Garden City, Gulf, and Northern Railroad Company called a meeting of the people of Haskell County for the purpose of considering railroad matters of interest to them. Evidently, they were impressed, for on February 24, 1910, the Santa Fe Monitor carried the news item that “Wednesday was a good day for Haskell County when the people decided by a magnificent vote to aid the Garden City, Gulf, and Northern Railway to the extent of $48,000 in bonds.” But even this did not bring a railroad to Haskell County. One wonders how the people ever paid their bonds.

In 1910, Santa Fe had a bank, two newspapers—the Monitor and the Republican, a number of retail establishments, professional men of all lines, a money order post office with one rural route, and a population of 150.

At that time, Santa Fe’s future seemed uncertain as the construction of the Garden City, Gulf & Northern Railroad through Haskell County appeared imminent.

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad expressed interest in building a line through Santa Fe. However, in 1911, railroad crews laid the tracks seven miles to the south of the county seat. A story in March 1912 said the railroad planned to name new towns along its line Satanta, after the Kiowa Indian chief, and Sublette, after William Lewis Sublette, a significant fur trapper, explorer, and entrepreneur.

On November 2, 1911, the following article appeared in The Santa Fe Monitor:

“Last Sunday’s Kansas City Post had a half-page illustrated burlesque on the moving of Santa Fe, and it was at a dandy. They succeeded in moving everything, but Sheriff Lucas was in his jail, full of prisoners, and they wouldn’t budge. Parsons Stanely was in the procession with the M. E. Church on his back, followed by the opera house, the quick meal restaurant, and a fat lubber toting a large beer sign. Some of the ladies said they were glad to see the saloon go, as they didn’t need it anyway. The most ridiculous part of it all was with old Si Plunket, who carried off the old town pump, which had been loafing around and arguing politics for nigh unto 40 years.

Seriously, Santa Fe hasn’t moved yet and may never move. Grading has not yet commenced on the road to which we are expected to move. At best, it will take nearly a year to complete. If Santa Fe finally decides to relocate, it will likely be a year or so before it is completed. We all hope it will not be necessary. Santa Fe is in the exact center of the county; there couldn’t be a better location, and it ought to remain where it is. So all this fuss seems to be a little premature.”

In 1912, there were 250 to 300 people in Santa Fe when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad was built through Haskell County. The line was constructed from Dodge City to Elkhart, Kansas, bypassing Santa Fe by seven miles and sealing its fate.

Steve Cave was the first to prepare to move, trading his Santa Fe lots to the railroad for new lots in Sublette. Jim Patrick moved his real estate office to Satanta, nine miles southwest of Sublette. A considerable part of Santa Fe’s population followed him there, but most of them went to Sublette.

On February 5, 1913, a referendum was held in Haskell County to relocate the county seat to Sublette, approximately eight miles to the southeast. It would be the first election in which women were eligible to vote. However, the measure failed.

Santa Fe residents weren’t about to give up. A January 1913 article in The News reported that Satanta joined forces with Santa Fe to prevent the county seat from relocating to Sublette.

By that time, there wasn’t much left of Santa Fe, except for the courthouse and “an old frame structure, the rest of the town being gradually broken up and moved away.”

Santa Fe residents continued to lobby for another railroad line through the town; however, it did not materialize.

The last issue of the Santa Fe Monitor newspaper was published on January 31, 1918.

Still, the fight continued with a special election on May 16, 1919. At the time, Santa Fe had a population of 75.

“In the special election held yesterday, Santa Fe lost its fight to continue as the smallest county seat in Kansas.”

— The News

The Santa Fe schoolhouse was sold for use as a church in Pleasant Prairie; the courthouse was demolished, and the lumber was used to build John Alexander’s farmhouse.

The matter went to the Kansas Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Sublette in December 1920. Afterward, a few remaining buildings in Santa Fe were relocated to Sublette.

The post office closed on July 31, 1925, with Agnes E. Lindeman serving as the last postmistress. Afterward, the mail was dispatched to Sublette.

Santa Fe was not officially abandoned until 1926, when the county commissioners issued an order vacating the land, although the actual abandonment was completed several years earlier.

By 1988, no buildings remained, and the townsite had been converted to farmland.

All that remains of the once-flourishing, busy community today is the Haskell County Cemetery. Initially serving the town of Santa Fe, it is located 5.5 miles north of Sublette on U.S. Highway 83

However, there is a meat-processing plant and a large feedlot in the area. Santa Fe was located along U.S. Highway 83, just north of its junction with U.S. Highway 160 and K‑144.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, December 2025.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Haskell County

Southwest Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Digging History

Haskell County Museum

Hutchinson News

Kansas Historical Society

Kansas Memory

Some Ghost Towns of Kansas by W.M. Richards

Wikipedia