College of the Sisters of Bethany in Topeka, Kansas, by Arthur Capper, about 1900.

The early history of education in Shawnee County, Kansas, cannot be made up from official records because very little of the early work of the county schools was recorded. Some information was gleaned only by searching through old letters, newspapers, and miscellaneous documents in the possession of old settlers.

The county superintendent’s office records furnish little information about the schools before 1865. The reports from that date to 1880 are more complete, and those from 1880 to 1892 are full and in excellent order. In 1855, there were several private schools in the county. It is not possible to ascertain when the first school was opened. Miss Sarah C. Harlan taught at a school in Topeka in the fall of this year. The school was held in a small building made of cottonwood boards until the first snowfall. This had a depressing effect. The teacher got married, thus establishing a dangerous precedent that her followers have maintained to this day. In the spring of 1856, Miss Jennie Allen and Miss Carrie Whiting taught private schools in Topeka. Schools of this character were also in progress at this time at Rochester, Tecumseh, Auburn, and other parts of the county. Only a partial list of names of these pioneer teachers of the early 1850s could be obtained. These included Sarah Harlan, Jennie Allen, Sarah Allen, Carrie Whiting, Olive Packard, Maria Bowker, Phoebe R. Plummer, and Jennie Penfield.

These teachers were the sisters, wives, and daughters of that sturdy, patriotic class of pioneers who came to Kansas not only to subdue the prairie sod and make homes for themselves but they came to uphold and fight, if need be, for the great principle of human liberty involved in the Free State issue. Those brave women who gathered about them in sod houses and log cabins, the children of “Bleeding Kansas,” are, perhaps, more deserving of a place in history than are some of the more noisy “statesmen” of that period. But those women teachers left a monument more enduring and precious to the state than any marble shaft or stately granite tomb. The barefoot boy who went trudging across the prairie to school, his ragged straw hat just visible above the prairie grass and golden rod, is the patriotic, active, pushing citizen, the “Kansas man” of 1893. The West knew and respected him, and the East was just getting acquainted with him.

In 1858 and 1859, the tide of immigration to Kansas and Shawnee County swelled proportionately as the echoes of the border war died away. Men came with their families and their goods and settled down to stay. Shawnee County was soon fairly well settled with a desirable class of citizens. The schools began to assume a more systematic condition.

In 1859, Reverend R.M. Fish was elected county superintendent of schools. The oldest document on file in the superintendent’s office was a notice of the organization of District No. 8, known as Rice District. It is dated July 30, 1859. There is no doubt that Superintendent Fish organized several districts under the territorial law this year, as the report of the Territorial Superintendent of Schools reports 14 districts in the county organized in 1859.

The schoolhouses were mostly built of logs. The first schoolhouse was built in District No. 11 in 1862. The logs were bought from Abram B. Burnett, the chief of the Potawatomi tribe, who died on the banks of the Shunganunga. This lazy stream flows peacefully along the shadow of Burnett’s Mound, a familiar landmark to the inhabitants of Shawnee County. The logs were hauled with ox teams, and the schoolhouse was built on the Fitzpatrick homestead near Burlingame Road. The house was “chinked” between the logs with sticks, stones, and mortar, but certain lawless, tow-headed boys would often knock the chinking out, in consequence of which acts the ventilation was all that could be desired, rather more than was agreeable, in fact, on cold mornings.

But the first school in this district was held in a long shanty owned by the Reverend Jesse Stone. It stood near the home of Perry T. Foster. The first school was taught in 1857 by Miss Olive Packard, a live Yankee girl of 16. Her career as a teacher was cut short by the arrival of a confident young man, who persuaded her to change her name to Mrs. William Owen, and again, the ranks of Shawnee County teachers met a loss. However, Mrs. Owen did not lose her interest in the educational affairs of the county, as she is the mother of ten children, five of whom later taught school in Shawnee County.

School district No. 23 in Topeka was well supplied with schools, judging from the local newspapers of that time. The Emigrant Aid Society erected a four-room brick schoolhouse near the corner of Fifth and Harrison Streets in 1856. The Topeka Association afterward bought the building of the aid society and used it as a public schoolhouse for several years. In the fall of 1859, on November 20, D.B. Emmert opened an evening commercial school in Museum Hall in Topeka. The Topeka Normal School opened in the above-mentioned brick schoolhouse in November 1859. The advertisement states that Professor C.W. Bowen, A.M., was the principal, and Miss Jennie Penfield, the teacher. The Topeka Academy, E.B. Conklin, principal, assisted by Mrs. H.E. Conklin, Mary E. Steele, and Clara Foster, opened September 12, 1859. The announcement was made that the following branches would be taught: Reading, spelling, writing, arithmetic, geography, grammar, U.S. history, Latin, Greek, and music on the piano and melodeon. In 1860, W.W. Ross, clerk of district No. 23, made a report, giving the names and ages of all the people over five and under 21 years of age in the Topeka district. The total number was 191. There were 50 enrolled in school. On March 12, 1860, Miss Mary Pickett opened a select school at the brick schoolhouse. Her terms for tuition were $3 per month.

The plan to organize a high-grade Christian college under the patronage of the Congregational Churches of Kansas was first presented at the General Association of Congregational Ministers and Churches meeting in Topeka in April 1857. A committee was appointed to secure a location for such a college. The college was built on 160 acres of land donated by Mr. John Ritchie in 1865. That year, the first building was erected at the corner of Tenth and Jackson Streets in Topeka. Work began in 1872 on the building known as Science Hall, and in the fall of 1874, the college was moved to this building, where its work continued for several years. It contained a chapel, recitation rooms, laboratories, lodging rooms, study rooms for faculty and students, a dining room, and a kitchen. Afterward, this building was purchased by the Board of Education and used for public school purposes.

In 1860, the clerk of district No. 1 in Auburn reported 108 school-age students and an enrollment of 86. Miss Brigham taught a nine-month school, receiving $32 per month. District No.3 in Wakarusa reported 21 children residing in the district. A six-month school was taught for three months by Mr. Thomas and three months by Miss Holliday. Mr. Thomas was paid $20 monthly, and Miss Holliday $10 monthly. In District No. 20, George B. Holmes, clerk, reported that a three-month school was taught by Miss Sarah W. Austin, who received $12 per month and board. District No. 22 in College Hill reported a three-month school in 1860 taught by Jane F. Nichols. District No. 4 maintained a four-month school and paid the teacher $25 monthly. Seventeen children attended school.

The drought of 1860 was due to crop failure and general hard times, and more than half the districts in the county failed to sustain any schools. Many homes were deserted; the arid and desolate prairie had empty houses. All honor to that noble band of teachers who kept the sacred fires of education burning throughout those days of trial while the hot winds withered the grass, burned the corn, and dried up the springs.

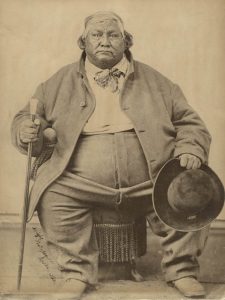

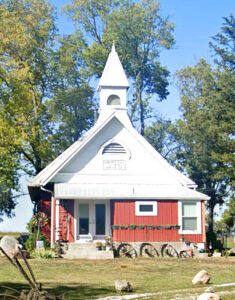

Reverend Charles Calloway, the first Episcopal clergyman in Topeka, Kansas, started the College of the Sisters of Bethany. It was first opened for students in 1860 under the charge of Reverend N.O. Preston, afterward pastor of Grace Church, was called “Episcopal Female Seminary.” Towards the close of the Civil War, the school was suspended for a short time but reopened in September 1865 under the charge of Reverend J.N. Lee, with 17 students. Commodious buildings were procured on the corner of Topeka Avenue and Ninth Street, and the institution, being the only Protestant school exclusively for girls in the State and under the care of experienced and able instructors, steadily increased in influence and popularity. In 1870, the school had outgrown the older building, and a new and elegant structure was commenced on a square of 20 acres, owned by the institution in the west part of the city, and was completed in 1873. After being removed from the new location, a year before the completion of the building, the name of the institution was changed to College of the Sisters of Bethany. This institution aimed to begin the education of girls in its kindergarten school and carry them through the primary, preparatory, and collegiate departments to complete their education.

Two school buildings — Wolfe Hall, completed in 1873 for $8,500, and Holmes Hall, completed in 1881 for $17,000. Wolfe Hall was five stories in height, 74×100 feet, and was built of rough Ashler stone. Holmes Hall is four stories in height, 40×80 feet, and of the same durable and suitable material. Plans for a significant wing three stories in height, 116×52 feet, and also of rough Ashler, were planned to begin in 1882 and completed in time for use during the ensuing school year for $22,000. When this work is completed, the school will have a total property of $159,000. Though the institution grew in the following decades, it closed in 1928.

In 1861, Reverend Peter McVicar was elected county superintendent. The Civil War began, and Shawnee County sent many of her best men to the front. This year’s reports are meager, indicating that little was done in the line of education. However, one clerk’s report found for 1861 shows a school taught during the year. James S. Griffing, of district No. 8, reported a three-month school taught by Miss Marcia Pierce. She was paid $30 per month, with 16 students enrolled. Reports from a number of the most vital districts in the county showed that no schools were in session in those districts. Schools were maintained at Topeka, Auburn, Tecumseh, and perhaps two or three other points, but it seems they were private schools.

In 1863, 20 clerks reported to the county superintendent that there were 978 students of school age (5 to 21) in the county, 593 of whom were enrolled. The average daily attendance for the entire year was 395. The average length of school term was four months. The teaching was done by 18 women and two men, who received $1,280.10. In 1865, nine more clerks were reported than in 1863. The total number of school-age students increased from 978 to 1,499 in two years. The enrollment had almost doubled to 1,022. The county employed 37 women as teachers who received an average salary of $28.50 per month. The five male teachers employed this year received an average of $41.20 monthly.

In 1865, a little wooden building on Sixth Avenue, the south side between Kansas Avenue and Quincy Street in Topeka, was rented for school purposes. In 1866, a school opened for colored children. The colored school was put in the attic of the building, and the lower room was used for white children. Baptist Hall was also used for school purposes in 1866, and in 1867, a school was held in the Gale Block. A school was also held in the basement of the building, on the southwest corner of Kansas Avenue and Seventh Street, at various periods.

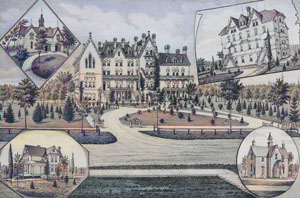

Washburn College in Topeka, Kansas, was chartered as Lincoln College on February 6, 1865. In the fall of the same year, a stone building for the preparatory department was completed on the southeast corner of the capitol square. The buildings had recitation rooms sufficiently large for 150 students, and the first term of the college opened in January 1866 with five teachers and about 30 students. The number of students in the first year was 92.

The name was changed to Washburn College on November 19, 1868, in recognition of a $25,000 gift from Ichabod Washburn of Worcester, Massachusetts, to avoid the confusion resulting from other schools using the name Lincoln. The college’s permanent buildings were erected on a beautiful site comprising a one-quarter section about one and a half miles southwest of the capital, which General John Ritchie donated to the institution. It then embraced an endowment of over $60,000 and 480 acres of land. The land near the city was soon sold for building lots at as high as $700 per acre.

Scholarships were established, tuition-free for children of home missionaries, students intending to become ministers or teachers, disabled soldiers, soldiers honorably discharged after two years, and children of soldiers who died in the service. Although under the special patronage of the Congregationalists, the college’s educational methods and policy are entirely unsectarian.

The college soon had a choice library, fine mathematical and philosophical apparatus, and every facility for acquiring a most thorough and liberal education. The courses of study were optional—business, scientific, academic, and collegiate. The college buildings consisted of a large stone hall first erected and occupied in 1874, although not fully completed until several years later, and three cottages used as dormitories. The first of these cottage dormitories was built with funds derived mainly from friends in Hartford, Connecticut, and was named the Hartford Cottage. The second was named the New Haven Cottage. Both these were occupied by female students. A third building for a men’s dormitory was completed in the fall of 1882.

On January 3, 1866, an academy or college preparatory department was opened to students under Reverend Samuel D. Bowker as principal and George H. Collier and Edward F. Hobart as assistants. When the school was opened, the courses of study offered were a college preparatory course of three years, consisting chiefly of Latin, Greek, and mathematics, and a ladies’ course of four years, in which instruction was given in French and some subjects in science. In the following year, a collegiate course of four years was added, in which Greek, Latin, and mathematics were the prescribed subjects until the third term of the junior year. In the remainder of the junior and senior years, limited courses were offered in philosophy and science. A scientific course was introduced in the third year of the institution’s history. These courses have been modified and enlarged from year to year, and there are now offered a college preparatory course, requiring three years of study for its completion, and collegiate courses of study leading to the degrees of Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, and Bachelor of Letters. The elective system has been introduced, making it possible for a student to select some line or lines of study in language, science, or literature that he may pursue for several successive years, thus deriving the benefit of consecutive study in one subject. Work is prescribed in sufficient subjects to prevent students from omitting studies that should find a place in every thorough education system. For graduation, a student was required to complete 15 full courses of study in addition to the work in English and rhetoric. Of these 15 courses, seven were prescribed, and eight were elective. Unless otherwise indicated, the courses of instruction continue through an academic year.

A steady increase in school population was shown until 1870, when there were 4,500 students of school age in the county, nearly five times as many as there were seven years before. The number of districts had increased from 14, in 1860, to 57, in 1870. There were 3,000 children enrolled, with an average daily attendance of 1,670. The school term averaged 61/2 months in length. There were 85 teachers in the county. The men were paid $50 per month, the women $35. It is interesting to note that the average wages of women teachers have gradually been nearing that of the men for the past 30 years in Shawnee County. The highest wages of any teacher in 1892, in the district schools of the county, is paid to a woman. The next highest is also paid to a woman. District No.83 paid Miss Emma P. Cooper $85 per month, and District No. 97 paid Miss Eliza Nagle $80. Nine women teachers in Shawnee County received $60 monthly and upward by 1893.

The College of the Sisters of Charity was established by the Catholic Church in 1875, under the charge of the Sisters of Charity, through the influence of Father Defouri, then pastor of the Church of the Assumption. It was located on Jackson Street near Eighth Avenue.

The Kansas Theological School, established by Bishop Thomas H. Vail for the education of Episcopalian clergy, is situated on Topeka Avenue between Eighth Avenue and Ninth Street. It was an incorporated institution and possessed property amounting to $25,000. The school building was large and commodious, serving the residents, the students, and the faculty. The Kansas Churchman, also published and edited by the Bishop, had a large circulation and influence in denominational circles.

In 1879, Hartford Cottage was built as a home for young women, and in 1882, South Cottage, since destroyed by fire, was erected to accommodate the increasing number of female students. In 1882, the building known as Music Hall was erected as a dormitory for young men. In 1886, two buildings were completed: Halbrook Hall, a woman’s home, and the Boswell Memorial Library, named respectively in recognition of gifts from Miss Mary W. Holbrook, Massachusetts, and Mr. Charles Boswell, of Hartford, Connecticut. The last building erected was the chapel, completed in 1890, to which Mr. W.A. Slater of Norwich, Connecticut, contributed $15,000. In 1889, the interior of Science Hall was remolded and adapted to the needs of the scientific departments. The total cost of buildings erected and owned by the college was nearly $150,000. The total value of all college property, including land, buildings, library, apparatus, museum, and endowment, was about $500,000. This property was acquired chiefly by individual donations.

In 1880, a most astonishing increase in school population was shown. Let us compare the statistics for 1880 with those of 1870. In 1870, the school population was 4,500; in 1880, 9,258, more than double. In 1870, 3,000 students were enrolled; in 1880, there was more than twice that number — 6,077. The average daily attendance increased from 1,670 to 3,542. In 1880, nine schoolhouses were built, totaling 91 in the county. In 1870, there were 52 in the county, six of which were made of logs. Between 1870 and 1880, the last log schoolhouse disappeared.

The report for 1892 showed that there were 98 organized school districts in the county. The school population was 17,079. There were 10,797 children as students, with an average daily attendance of 7,472. It took 228 teachers to train this little army — 82 men and 146 women. The men received an average salary of $58 per month, and the women $50 per month. The value of the school property was estimated at $671,232. There were 240 schoolrooms in the county. The amount of money raised and collected for school purposes during the year was $256,000; the amount paid out was $197,000, leaving a balance on hand for the year of $59,000. The county’s educational system was satisfactory, although far from perfect. In 1889, the superintendent introduced a plan of graduation and classification, which unified the county’s work materially. A systematic record of each student’s work was kept in a permanent register, separate from the attendance register. By referring to this, a new teacher could ascertain what work had been done by the students the previous term. Reports of each student’s classification, graduation, and standing were sent twice each year to the superintendent�at the end of the first month and at the end of the term.

A uniform system of textbooks was used throughout the county, having been adopted in September 1891 for five years. The books in use were White’s two-book series of arithmetics; Butler’s geographies, descriptive and physical; Reed’s Speller; Hutchinson’s Laws of Health, and “The House I Live in,” a Primary Physiology; the Eclectic United States History; Harvey’s English Grammar; Powell’s “How to Talk;” Roudebush’s Writing System; Thomson’s Intellectual Arithmetic; Thomson’s Algebra; Gage’s Physics; Williams & Rogers’s Bookkeeping; Graphic Object Drawing; the International Dictionary; Townsend’s Shorter Course in Civil Government; and Canfield’s Local Government in Kansas.

Soon after adopting these books, a Course of Study for the Schools of Shawnee County began to be used. It was adapted to the needs of the district school’s teacher and made the district school’s graduation practicable. The normal institutes of Shawnee County were a great help to the teachers. Few institutes were held in the early days. The first institute ever held in the county was held on April 21, 22, and 23, 1865. Lectures were given by Reverend P. McVicar, Professor C.H. Haynes, and Honorable I.T. Goodnow. Discussions of practical questions of interest to teachers were also held. In 1876, a four-week normal institute was held. Miss Una Hebron, who was then county superintendent, managed the institute, and it was very successful. In 1877. a normal-institute law was passed, requiring each county superintendent to hold a normal institute in his respective county for a term of not less than four weeks.

Teachers’ associations have been maintained regularly since 1880. Before that time, they were not very successful or regular. A program is prepared and printed in September each year. Papers are read and discussed, current events are discussed, and scientific and literary topics are introduced. The teachers derived significant benefits from these meetings. In 1892, a new feature was added: lectures by prominent men of Topeka were given every other month. This proved a pleasing and satisfactory innovation.

The school buildings in the early 1890s had a somewhat different style of architecture from those of 30 years before. Instead of the rough log structure on a prairie slope surrounded by wild grass, goldenrod, and wild roses, the Shawnee County schoolhouse was more practical and nondescript. It was generally built of wood, neatly painted, and surrounded by a neat fence and graceful shade trees. One district, No. 35, built a brick schoolhouse for $10,000, and several cost $4,000 and upward. Nearly one-half of the schools are supplied with good libraries. Many school boards furnished daily papers, magazines, and literary papers in the schoolroom.

A few districts in Shawnee County had almost stood for 30 years. Some schoolhouses were dirty and out of repair, yards unfenced, outhouses in disgraceful condition, windows broken, and no school apparatus. But such schoolhouses were rare exceptions.

The lowest wage paid to a teacher in 1892 was $30 per month. There was a growing demand for trained teachers. Schoolmen, school women, and parents realized that it did not pay to train teachers at the expense of their own children. They saw the advantage of good, normal schools, and the time was far distant when a young man or woman would not attempt to teach in a public school without first receiving professional training.

On October 21, 1892, the schools of Shawnee County observed the 400th anniversary of the greatest discovery the world has ever known. “Columbus Day” was more generally observed, and in a more fitting manner, than any other special-day observance in the county’s history. Nearly every schoolhouse raised a flag and followed the official program prepared by the national committee. It was common in most of the county schools to observe Washington’s birthday, and many of the schools have had flags floating over them for several years.

Shawnee County Historic Schools

| School | District | Years of Operation | Location |

| Curtis Junior High | ?? | 1927-1976 |

This three-story Collegiate Gothic school in Topeka, Kansas, was built of limestone, brick, and ceramic tile. Curtis Junior High was closed in 1976 due to consolidation. Now called Pioneer Curtis Homes, it serves as an apartment building. It is located at 316 Northwest Grant Street. |

| Disney | 27 | ?? |

This brick school building, located at 8901 SE Ratner Rd, near Berryton, Kansas, now serves as a private residence. |

| Dover High School | ?? | 1935 |

A one-and-a-half-story Collegiate Gothic-style red brick building was closed during school consolidation. It is vacant, but the Elementary School occasionally uses the gym. There is a red brick addition to the north. It is located at SW Douglas Road. |

| East Topeka Junior High School |

This art-deco-style school, located at 727 Southeast Lake St. in Topeka, was built by the Public Works Administration in 1935-1936 to become a high school. It has a large auditorium and gym for a junior high. It served East Topeka until 1980. At that time, it had a minority enrollment of 71%, and it became one of five junior high schools to close beginning in 1980-1981. After privately selling it for $50,000, it was discovered it had asbestos, and removal would cost too much. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in January 2004. Today, the building is abandoned. |

||

| Elmont | ?? | 1917-1963 |

The former Elmont school was built in 1917 after a tornado on June 5 destroyed what was then the current school. Construction began on the $5,000 school in September-October of that year, with the school operating as a one and eventually two-room school until about 1963, when the school closed permanently after the current Elmont Elementary School opened its doors. Consolidation of rural one and two-room schools in the 1950s and 1960s brought about the closure of all one-room schools in Shawnee County. It is a one-story building with chipped white-painted wooden siding atop a red brick foundation and a chimney on the roof. An old wooden outhouse serves as a vestibule to the entrance. It is located at 2921 NW 62nd Street in Topeka, Kansas. |

| Gage Elementary School | ?? | ?? |

This two-story brick building in the Classical Revival style from the late 19th and 20th centuries once served as Gage Elementary School. Today, it is the Topeka Civic Theatre & Academy, located at 3028 Southwest 8th Avenue in Topeka, Kansas. |

| Golden Rule | 54 | 1890 |

This Queen Anne-style school has a pronounced bell tower with fish-scale shingles at the gable end. The rectangular wood-frame structure currently serves as a rental residence. The old Golden Rule School is at 5444 Northwest 39th Avenue in Topeka, Kansas. |

| Hayden | ?? | 1939-?? |

The three-story building has a concrete foundation, buff brick cladding, and a standing seam metal cross-gable roof. A four-story tower rises at the intersection of the gables on the south elevation. A flat-roof wing projects from the east end of the north elevation. Mission Revival-style elements include the four-story tower, arched openings, and decorative brickwork. Non-historic fixed aluminum windows with muntin grids forming a variety of geometric arrangements fill each window opening in each elevation. It is part of the Church of the Assumption Historic District and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in July 2015. It is now used as a commercial building. It is located at 212 Southwest 8th Avenue. |

| Kelsey | 99 | ?? | Five miles east of Oakland |

| Lone Tree | 31 | ?? |

The old wood-frame two-story Lone Tree School serves as a residence today. It is located at 5039 Southwest Hoch Road near Topeka, Kansas. |

| Monroe Elementary | ?? | 1926-1975 |

The Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas, is the site associated with the landmark Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka case and the U.S. Supreme Court decision handed down on May 17, 1954. After the Sumner Elementary School of Topeka refused to enroll Linda Brown based on race, it led to the case that would give the name to the court’s decision. Before the Supreme Court verdict, Linda Brown attended the segregated Monroe Elementary School. The location of both schools and the quality of education they provided to the plaintiffs were material to the finding of the Supreme Court in the Brown decision. The U.S. Supreme Court concluded that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” which denied the legal basis for segregation in schoolrooms, initiating a revolution in the expression of equality and the legal status of black Americans. The two-story, five-bay, red brick Italian Renaissance-style Monroe School was constructed in 1926 by the School Board of Topeka, Kansas. At that time, it was one of four elementary schools in Topeka serving the black community. The school was closed in 1975 due to declining enrollment. The school was declared a National Historic Site in December 1992 and opened to the public in 2004. Brown vs. Board of Education National Historic Park, located at 1515 SE Monroe Street in Topeka, features interpretive programs to inform and educate visitors on local and national issues relating to the Brown v. Board decision. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. |

| Oak Grove | 26 | 1871-1944 |

The old Oak Grove School near Tecumseh, Kansas, was built in 1871 and closed in 1944. The one-story stone rectangular building was designed in the vernacular style with a Gable-Front roof. The vacant building is located at 7211 SE 2nd Street near Tecumseh, Kansas. |

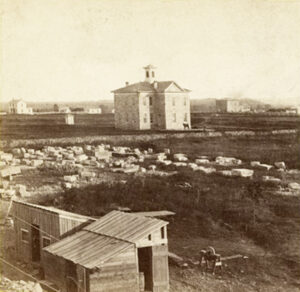

| Potawatomi Baptist Manual Labor School | 1855 |

Potawatomi Baptist Manual Labor School was part of the Pottawatomie Baptist Mission Site. In 1847, the Pottawatomi Indians were removed to a reservation on the Kansas River just west of present-day Topeka. Baptist missionaries Robert Simerwell and Reverend Johnston Lykins moved to the reservation the following year. Lykins supervised the construction of various buildings, including the schoolhouse. As superintendent of the Pottawatomie Baptist Manual Labor School, he sent a report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs on September 30, 1849. In it, he described a stone building in the process of completion. The estimated cost of the school building was $4,800, which was to be paid by the federal government under its program of supporting manual training schools for Indian children. In 1849, there were 39 students and two teachers. The training was to be offered in woodworking, metalworking, farming, school education, and religion. The early 1850s seem to have been troublesome times for the Indian schools. It apparently closed in 1855 when it was transferred to the Southern Baptist Convention for reorganization. Reopened in 1856, the school had increased enrollment and its greatest success from 1858 to 1860. It was closed again in 1861 when the federal government dropped its support because the Southern Baptist Convention, which supervised the school, was identified with the Confederacy. The Pottawatomi made an unsuccessful attempt to have the school reopened in 1869. A few years later, the Baptist mission board sold the 320 acres on which the mission buildings were located to Robert I. Lee, who converted the building into a racehorse stable. The location was near the Kansas River on the California- Oregon trail. The building is one of the few remaining Kansas links to that era. The date of construction makes it one of the oldest buildings in the state. It is also the only structure remaining from Baptist Indian mission activities in the state. The Pottawatomie Baptist Mission, including the school, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in September 1971. The three-story stone building was built in the Vernacular style in 1855. It is located at 6425 SW 6th Avenue in Topeka, Kansas. |

|

| Stach | ?? | 1877-1956 |

This wood-framed, one-story building designed in the vernacular style has two outhouses behind the school. It was named after Czech immigrant John Stach, who donated the land to the school in Jackson County. The belfry, cloakroom, and porch were added in about 1915. The school closed in 1956 and was used as a community space until the late 1960s. It was relocated from Delia’s vicinity in Jackson County and is now part of the Kansas State Historical Society Museum at 6425 SW 6th Avenue in Topeka, Kansas. |

| State Industrial School for Boys | NA | 1881-1971 | This State Reform School was established under the provisions of an act passed by the legislature of 1879, which appropriated $35,000 to erect buildings, equipment, and supplies. The goal of the school was to reform and care for dependent, neglected, and delinquent boys under the age of 16 who had committed criminal acts. It was built in Topeka, Kansas, and opened in 1881. |

| Union Hall | 1893-1895 |

This old school was constructed as Union Hall, a community building for the African-American population of Tennessee Town in the 1890s. In 1893, this building served as the temporary home of Sheldon (aka Tennessee Town) Kindergarten in 1893-1895. It was one of the first African-American kindergartens in the United States. By 1895, classes were held at Central Congregational Church. The building was also used as an African-American church and a multi-faceted and essential center of activities for African-American residents in Topeka. At some point, it was converted to a single-family dwelling. The one-story rectangular building is clad in wood siding with metal siding strips in the primary elevation’s upper section and rests on a concrete block foundation. The primary elevation (east) holds a flat-roofed partial-width porch supported by an iron scroll post, concrete decking, and steps (south) with iron railings. A flat-roofed stoop entrance supported by iron posts is on the south elevation. It is located at 1177 Southwest Lincoln Street in Topeka, Kansas. |

|

| Van Buren | ?? | 1910-?? |

This three-story square brick building, with a flat roof and parapet, was designed in the Late 19th & 20th Century Classical Revival style. It has a symmetrical facade with a recessed entry between a tall pediment with recessed panels; above are pained pilasters joined by single Ionic-like capitals. It has a segmental arch, a cornice with large dentils, and a parapet with a three-part arched crest. Vacant today, it is located at 1601 SW Van Buren Street in Topeka, Kansas. |

| Victor | 101 | 1891-1954 |

It was initially built in 1891 on a plot of ground at the southwest side of the intersection of Crawford Road and 86th Street in the Rossville vicinity. This one-story rectangular wood frame building was designed in the vernacular style with a gable roof. When it closed, there were only four students. The building was then donated to the Mid-America Fairground Association and relocated to the Fair Grounds in Topeka, Kansas, in 1957. In 1981, it was acquired by the City of Topeka and relocated to its current location in Old Prairie Town, which features several other historic buildings at 124 NW Fillmore Street. |

| Wakarusa | 3 | ?? |

The old Wakarusa School is a two-story rectangular brick structure with a flat roof. Bricks are laid in the stretcher bond style, and the cornice is constructed of cut stone surrounding the building. The entrance projection has a steep gable. A shelf with consoles is balanced between the two windows on the second story and over the entrance. Running above the second-story windows is an entablature of brick in the header bond. Attached to the rear of the school is a later addition. It appears to be used as a residence today. It is located at 9832 SW Olive Street near Wakarusa, Kansas. |

| West Union | 58 | ?? | West Union Road, just north of I-7 |

| Willard | ?? | 1915-1963 |

Constructed in approximately 1915, the bricks used in the foundation were repurposed from a previous brick schoolhouse known as Reader’s School (1891-1915). Residents Chet Skidmore and Dave Stitt cleaned the bricks from the old schoolhouse for use in the foundation of this building. This one-story T-shaped rectangular wood-frame building was designed eclectically with a side-gable roof. This school closed in 1963 due to declining enrollment. Today, the building is a private residence at 208 Darling Street in Willard, Kansas. |

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, last updated October 2024.

Also See:

One-Room, Country, & Historic Schools of Kansas

Sources:

Abandoned Kansas

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Columbian History of Education in Kansas, Compiled by Kansas Educators, Kansas State Historical Society, 1893.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883

Kansas State Historical Society, The Columbian History of Education in Kansas, Hamilton Printing Company, Topeka, KS, 1893

Kansas Historic Resources Inventory