Stanley, Kansas.

Stanley, Kansas, was situated on the Kansas City, Clinton & Springfield Railroad eight miles southeast of Olathe in the eastern part of Johnson County. It was one of the new towns that grew after the railroads were built and was the shipping and supply town for a rich farming district.

Situated in a busy part of Johnson County and overshadowed by Overland Park, it was annexed by the much larger city in 1985 and is officially an “extinct town” today. The Stanley neighborhood is part of the Kansas City metropolitan area.

The site that became Stanley was initially assigned to the emigrant Shawnee Indian tribe in 1854. The land was divided among eight chiefs, one of whom, Chief Black Bob, was awarded 33,392 acres in the southeastern corner of Johnson County. The land was ideal for Black Bob and his 167 tribe members, primarily hunters and fishermen. The land had many creeks, including the source of the Blue River.

Though most of the area was set aside for the Black Bob Indians, white settlers also began to locate here. The area was about three miles west of the Missouri border. With its proximity to Missouri and the issue of slavery on the line, Oxford Township attracted primarily southern settlers from Missouri, Kentucky, and Arkansas. In 1865. Over 50% of the township’s population was native southerners. The town had a water source south of Negro Creek, which flowed eastward into the Blue River.

On July 4, 1866, the families of John Dougan, John McCaughey, and Adam Look arrived from Ohio and settled on the land destined to become Stanley. That year, J. H. Hancock also settled in Stanley and took an active interest in the Grange work of Johnson County. He held the office of overseer in the State Grange at one time.

Sherman Kellogg, originally from Vermont, came to Kansas in 1864 and settled in Stanley in 1867. Kellogg was a notary public, Justice of the Peace, and the cashier of the State Bank. In Stanley’s early years, a newspaper called the Stanley Review was published for about six months. Mr. Kellogg, the cashier of the State Bank, was interested in it and was its editor. It was printed in Kansas City, Missouri, by a firm that printed several country weeklies. Unfortunately, the firm’s cashier took off one day, leaving them stranded, and Mr. Kellogg made arrangements with another company to fill the unexpired subscriptions. However, the paper was an anti-prohibition sheet, and Mr. Kellogg asked them to cease sending them out. The Review had about 300 subscribers at the time it was suspended. The Review had about 300 subscribers at the time it was suspended.

A post office was established on March 19, 1872, in Heck Mardis’ general store. It was named Stanley in honor of Sir Henry Morton Stanley, a journalist and adventurer who covered the “Indian Wars” in Kansas for newspapers.

In 1872, the settlement gained a branch of the Kansas City, Clinton, and Springfield Railroad on the southern edge of town. The rail line traveled eastward from Olathe into Missouri. It was known as the “Leaky Roof Railroad” because freight cars could not seem to repel rain from the cargo inside.

In 1879, President Rutherford Hayes officially removed Black Bob and his tribe to Oklahoma, ending all Native American settlement in Johnson County. Afterward, the land was opened up to new settlers.

The population shifted from southern settlers to new residents from the “North-Midland” states of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio by 1880. That year, the census noted 55 families in Stanley and 368 in Oxford Township, totaling 1,158 people. Most residents were farmers whose most common crops were corn, rye, soft winter wheat, pumpkins, melons, squashes, and tomatoes. Dairy farming was also common.

The first settlers stressed the importance of education for their children and set the goal to establish a school every two miles. These schools were built by neighbors and housed the first through twelfth grades on donated land.

In 1910, there were several general stores, an implement and hardware house, a hotel, a lumber yard, a money order post office, telegraph and express facilities, a public school, several churches, and a population of 200.

In 1915, Stanley had several successful stores, including Allison & Son’s general merchandise, S. L. Runner’s drug store, Allen’s Cash Grocery, and the Stanley Lumber Company. Stanley’s Bank was organized on April 3, 1905, and was very successful. Other businesses included P. C. Brown & Son’s restaurant, two blacksmiths, a barber, a physician, and an auctioneer. At that time, Stanley’s population was 300.

In 1919, a grain elevator was built. At that time, railroad traffic consisted of four passenger trains daily.

In 1920, Stanley Rural High School was constructed for the 9th through 12th grades. When it was completed in December, it had 40 students enrolled.

The town’s population remained relatively constant for the first half of the 20th century, with a population of 1,442 in 1930. In 1934, the railroad tracks were removed.

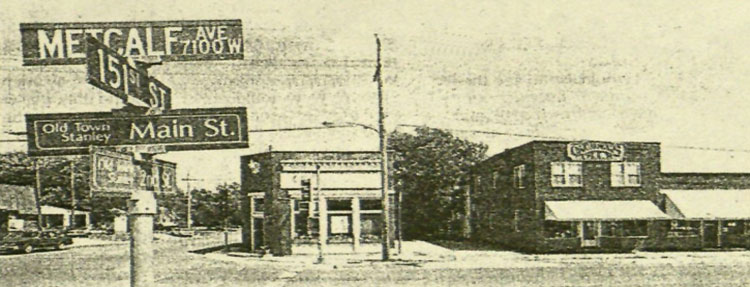

In 1957, the Kansas City Star newspaper published a notable forewarning for Stanley residents in an article on “Suburbia.” The article had a photograph of downtown Stanley with the caption, “The peaceful days of Stanley, Kansas, may be numbered as the suburban push spreads south and southwest.” The business district was only six miles from residential areas near 103rd Street, and Nall and Stanley were moving closer to becoming a participant in the suburban sprawl of Johnson County, whether the residents were ready for it or not.

Stanley’s population peaked in 1960 at 1,709.

In 1965, the towns of Stanley and Stilwell consolidated into Southeast Johnson County Unified School District #229. Soon, plans were made to build a new high school, which opened on 159th Street in 1971. The new school was renamed Blue Valley High School. The old school was later renovated for use as the District Office.

Blue Valley High School in Johnson County, Kansas, courtesy of Google Maps.

The threat to residents was the city of Overland Park. Spurred by continued development, this city sought to expand its boundaries southward and absorb the land around and including Stanley itself. Despite resistance that included lawsuits by Stanley residents, its status as an unincorporated community stood a slim chance against the larger city of Overland Park.

On August 20, 1971, Overland Park attempted to annex Stanley. The Overland Park Council approved the annexation after an eight-day “expansion campaign.” Stanley residents were outraged and created the Johnson County Rural Community Association to investigate the legality of the annexation. Eventually, they took the case to court.

The annexation attempt, however, merely magnified the issue at hand: that development in Johnson County was pushing farther and farther south, and Stanley was in the way. Stanley’s post office was discontinued on January 5, 1973. The post office, then called “Shawnee Mission,” was still located at 15119 Metcalf, right in the heart of Stanley, and letters were still being addressed to residents of “Stanley,” but the postal service did not recognize it as a town.

In September of 1973, the Johnson County District Court Judge ruled the Kansas Annexation Law unconstitutional and “nullified Overland Park’s controversial 1971 annexation of 4,640 acres.” The case was taken to the Kansas Supreme Court, where in November 1974, the court upheld and reversed the District Court’s decision. The Supreme Court upheld the Kansas law regarding annexation but determined that the annexation attempted by Overland Park of Stanley was “invalid.”

Stanley residents faced more substantial challenges than discrepancies in mailing addresses, however.

Throughout its history, Stanley remained an unincorporated community. It had no mayor or city council, and the county provided services for residents, including the fire department. Though Stanley had “community spokesmen and leaders” who voiced concerns to the county on behalf of residents, none were elected or had any political clout.

In 1978, Stanley tried to make itself official and applied to become an incorporated city of Johnson County, but the attempt failed.

Stanley tried again to incorporate in early 1985 but was again denied by the County Commissioners. This was due to a significant requirement that the community had a large enough tax base to provide its own services, which Stanley did not have.

In March 1985, 160 acres at 151st and Nall (less than a mile east of Stanley) were annexed by Overland Park at the request of the landowner, developer JC Nichols, Inc. Nichols was proposing a 500-home subdivision on the land and felt that Overland Park could provide the services the future residents needed. On May 8, 1985, Stanley was an unincorporated community annexed by Overland Park despite resistance from residents. This included about eight square miles and 1,000 new citizens.

The final approval of annexation rested with the Johnson County Commissioners, who, on August 8, 1985, unanimously approved the proposed annexation by Overland Park.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2025.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Johnson County

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Blair, Ed; History of Johnson County Kansas; Standard Publishing Company, Lawrence, Ks; 1915.

Griffin Page, “Stanley, Johnson County,” Lost Kansas Communities, Chapman Center for Rural Studies, Department of History, Kansas State University, 2013

Wikipedia