Sunflower Ordnance Works was a powder and propellant manufacturing facility in northwest Johnson County, Kansas. It was established in 1942 on 9,063 acres, three miles south of De Soto. Located about 15 miles from the Kansas City metropolitan area and Lawrence, the Kansas River, and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad connected these cities.

Soon after the plant was established, Sunflower Village was built just north of the plant, across from Kansas Highway 10. The village was not included in the original plans for the plant. Still, it soon became necessary as the area communities became too crowded, and rubber and gasoline rationing during World War II made transportation to and from the plant difficult.

Although the United States constructed an extensive munitions manufacturing network during World War I, few facilities survived the country’s “return to normalcy” and disarmament of the 1920s. The dismantling of powder and explosives works was very thorough. By the mid-1930s, there were only four active manufacturing plants for smokeless powder, which was the primary propellant for American military ammunition.

As a first step toward expanding American smokeless powder capability, the U.S. Ordnance Department began planning for a series of new plants in 1937-1938.

With the fall of France to the Nazis in the summer of 1940, Congress appropriated defense funds for constructing three new powder plants. An additional 25 plants were planned after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941. Sunflower Ordnance Works was among those 25 plants.

The government purchased about 10,474 acres of relatively flat, clear, and lightly wooded land in Johnson County, Kansas. The Army Ordnance Department announced on February 26, 1942, that it would build a plant near De Soto because the area had met the criteria, which included proximity to good highways and railroad lines, good sources of water, and Kansas City and Lawrence could house the necessary labor force.

The land purchased comprised some 150 farms and the small community of Prairie Center. The town’s cemetery was moved outside the plant boundaries to the west, some houses were moved to nearby communities, but the vast majority of its buildings were razed.

The Hercules Powder Company signed a contract to operate the Sunflower Ordnance Works (SOW) in May 1942. On May 8, 1942, ground was broken for the Sunflower Ordnance Works only four months after the United States had entered the war.

Within a few weeks of the plant’s initial announcement, cars loaded with people and all of their belongings began to line the Kansas highways as people poured into the area seeking jobs. Initially, it was announced that 4,000-6,000 employees would be expected to live in surrounding areas and commute to the plant.

Most of the staff would initially reside in Lawrence, where the Army and Hercules officials set up operations. Following the initial construction announcement, Lawrence set up housing and transportation committees to facilitate support for the plant.

Soon after, trailers were added at the plant site to provide staff and construction workers with round-the-clock access. On December 15, 1942, “Trailer Town” opened on the plant grounds. Trailer Town provided basic necessities, including water and power, and a row of outhouses served the residents. This temporary community grew to 400 units and included a grocery store and school.

SOW recruitment offered employees “ideal working conditions” and “complete uniforms with shoes.” Kansas farmers were encouraged to apply via locally distributed flyers. Farmers had good reason to consider the regular wages employment would bring. While agriculture was a necessary industry throughout the war, farmers had to deal with rationing their resources and price controls on their products. SOW offered a full-time job with regular wages, a stability unknown in the previous decade.

Recruitment trucks traveled 100-mile radius advertising SOW employment. Before the plant was built, people came from nearby states, including significant numbers from Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, where recruiting teams were sent to encourage skilled laborers to apply. So many people came from Arkansas and had their own section of town in Eudora. One of the primary reasons for this migration, in addition to the offer of a steady job, was the pay was often as much as five times as much as workers had previously earned.

Patriotism, however, seemed foremost in everyone’s mind. School teachers worked summers at the plant, not simply for the extra earnings, but more importantly to do their part “to bring their husbands and brothers back from war.”

In surrounding communities, the situation seemed to change overnight. In 1941, Eudora had no hotel or boarding house and only about seven vacant homes. Within three months, the town’s population had doubled to 1,800, and there were as many as 150 trailers in fields, yards, and other empty spaces.

In both De Soto and Eudora, homes rented out all available space, including garages, outbuildings, basements, and spare rooms. People slept in cars and tents as weather permitted. Restaurants, banks, laundry, and service stations were open around the clock as the communities struggled to keep up with demand.

“The impact of such a horde of people descending on a little town must be lived through to be understood. At one time, there were eight restaurants, some operating 24 hours per day (including their jukeboxes with ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama.’)”

— De Soto historian Dot Ashlock-Longstreth

A rail spur to De Soto was completed in July 1942, allowing construction to speed up with the faster transit of materials. Bus companies added routes synced to Sunflower shifts to link Eudora and De Soto with Lawrence and Kansas City. Carpooling became a requirement for employees.

By September 1942, it was clear that SOW needed to provide living quarters for some of its employees. By late 1942, the government announced the construction of a housing project north of the plant.

On March 23, 1943, less than a year after construction began on the plant; the facility produced propellants for small arms, cannons, and rockets.

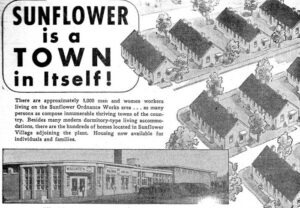

In an April 1943 plant newsletter, the Ordnance Works published a rendering of the proposed housing development. The article noted:

“Thousands of trees and bushes will lend beauty to the 175-building site. The housing units will be 40 feet apart with a variety of sizes of units ranging from two to five bedrooms, providing a total of 852 dwelling units. An overpass from the plant across Highway 10 will lead into the project’s entrance where the town’s stores and community buildings will be located.”

By May 1943, 350 employees lived in the plant dormitory with rental rates from $10.85 to $15.50 per person. However, this limited housing was insufficient to impact traffic conditions or lack of housing.

However, work continued on the housing project. Designed by landscape architects Hare & Hare, the Village layout embraced the Garden City design principles, resulting in a self-reliant community that would provide a safe and healthy environment. The plan was organized around curvilinear roads separating pedestrian and vehicular traffic. The Village incorporated green space and landscaping with recreational facilities, including ponds and playgrounds. Employees were encouraged to form teams and compete against other area teams. Sunflower Village also included commercial and community buildings. The individual buildings were utilitarian in style and function, reflecting their rapid construction and plans for limited life spans.

The first residents moved into Sunflower Village on August 1, 1943, and employees could walk to work. It was filled to capacity in less than a year. However, as many as 1,100 people still arrived daily via bus and rail.

On August 15, 1943, church services were first held in Trailer Town.

In September 1943, 300 acres were set aside for a large communal victory garden. Families often shared their recreation and their work.

At about the same time, the Community Center opened and quickly became the center of Village activity. The building served various uses, including housing management offices, recreational facilities, a medical clinic, daycare, and a library, boasting a full kitchen, gymnasium, game room, and auditorium. The auditorium hosted dances on Saturday nights, church on Sunday mornings, and movies at various times. The center also provided educational services for adults, including extension courses and hosted space for various clubs.

The Commercial Center was planned to house a drug store, grocery store, barber and beauty shops, and a post office. Walgreens Drug Store opened in September 1943, and a post office opened on December 2, 1943. A grocery store opened in March 1944. The commercial building would also house a shoeshine parlor, dry cleaners, specialty shops, a Sears catalog store, eating establishments, and a bar in the following years.

When Sunflower Village first opened, children, attended school in make-shift classrooms at Trailer Town. Arrangements were made with De Soto school officials that allowed fourth, fifth, sixth graders, and high school students to attend. The new Sunflower Grade school opened on January 3, 1944.

By May 1944, less than a year after the first residents moved into Sunflower Village, the population had reached 1,650.

A Phillips 66 gas station selling Firestone accessories opened in 1945 at the southwest corner of the original Village site, facing Highway 10.

By 1945, Sunflower was the largest powder plant in the world. Employment peaked at 12,067 in June 1945, with 8,000 additional people employed in ground maintenance, roads, railroads, and buildings. Women then made up more than 60% of Sunflower’s payroll. The three production lines initially planned grew to eight before the end of the war.

Though hundreds had flocked to the area, in the beginning, manpower remained a problem for the plant throughout the war. With pressure to produce more product faster and transportation problems, turnover rates were high. As a result, the Lawrence and Kansas City newspapers saw ads almost weekly. The people that worked at the plant were from all backgrounds and included hundreds of women, many of whom had never worked outside the home. At its peak, the plant encompassed 4,500 buildings connected by 175 miles of roads and 70 miles of railroad track.

In 1945, the government completed the second and third additions to Sunflower Village. This addition to the east, which included 580 pre-fab units and a 15,000-square-foot recreation hall, was referred to as the “New Village.” The 853-unit addition built in 1943 on the west side was called the “Old Village.” By then, housing, the school, and traffic were filled and overflowing.

Though Sunflower Village was a government-built community operated by the Federal Public Housing Administration, it had all the appearances of a “Company Town.” Throughout the war years, the Village was a bustling community.

In the meantime, De Soto’s population had increased from 400 to over 1,000.

When World War II ended in September 1945, production slowed by half and continued to decline. Soon only a few hundred workers were needed.

Many workers headed back to their home states, and Sunflower Village was mostly vacated. However, returning soldiers would soon occupy many of these buildings as the village transitioned from war-worker housing to homes for veterans, active-duty military, and area students. Keeping the rents low, the village attracted hundreds of people.

“Today the hundreds of four-to-six apartment buildings stretch along the streets. The colored roofs add attraction to the little town. The streets are paved, and sidewalks border the streets. Lawns are grass-covered, and many of the tiny yards are gay through the summer with flowers. Victory Gardens produced food for many a Village family and furnished a communal gathering spot besides, situated as they were in one large space reserved for that purpose.”

— Kansas Magazine, 1946

In October 1946, Sunflower Ordnance Works began to produce ammonium nitrate fertilizer to export to allied and U.S. occupied countries. This would assist farmers in supplying produce to reduce starvation and malnourishment in war-torn countries of Europe and Asia.

In July 1948, the ammunition part of the plant was placed on standby. However, fertilizer components continued to be produced until about 1955.

When the United States entered the war in Korea in June 1950, propellant production was again needed. In January 1951, the SOW was reactivated and underwent a $25 million rehabilitation to produce additional types of propellant utilizing 4,000 construction workers.

During this conflict, the plant employed 5,347 workers, including 758 employees who lived at Sunflower Village and 874 who commuted daily from Lawrence. In addition, more than 500 employees commuted from De Soto and Eudora, while others made the 100-mile round trip daily from Kansas City.

After the Korean Armistice in July 1953, SOW production remained steady for a short time, including the number of employees. However, the employee population fell to 4,000 by April 1954 and 2,300 by December 1955. Through 1956, the work roster remained steady at 2,300.

In the spring of 1957, it was announced that the plant would be deactivated, but it was delayed for over a year, retaining 450 workers. The recreation hall closed in 1957. Sunflower Village and the plant remained on standby with a sparse maintenance crew.

In the 1950s, the two Sunflower Village additions that were built in 1945 were removed.

Soon the drug store and the grocery store closed, which reportedly “turned the Village into a ghost town.” The Sunflower post office closed on July 31, 1958. This left only a beauty shop, a tv and radio shop, a tire shop, and a filling station, only two of which were located in the Commercial Center building.

In December 1959, the government sold a 176-acre parcel that contained the original Sunflower Village, including residential units, commercial, and community buildings, excluding only the Sunflower Grade School. The buyer was Louis H. Ensley, who operated Sunflower Village as a low-income housing project from 1960-1971. The government still provided the water supply for the houses, and Ensley worked with local utilities to enhance infrastructure throughout the development. Bell Telephone installed telephones, and Union Gas Company connected all residences in the Village to a central propane tank. Ensley also rented one of the former dwelling units to establish a church.

By November 1960, the population of the Village had reached 1,280, and Ensley worked to create and support recreational activities for residents. In 1963 Ensley built an in-ground swimming pool behind the commercial center at the southern end of the Village.

Under private ownership, the Village quickly rebounded in the early 1960s. Several businesses reopened in the Commercial Center, including a laundry, dry cleaners, beauty and barber shops, a television and radio repair shop, and a new grocery store. Village owner Louis Ensley opened a used furniture shop in the former drug store and operated the “Dairy Bar,” a small snack shop, in one of the storefront spaces, which eventually expanded to include a game room with pool tables.

Ensley leased the recreation building to a moving and storage company as a warehouse in the early years. The building was demolished in the 1990s.

During the 1960s, private companies were allowed to rent the plant facilities. Trans World Airlines, United States Industrial Company, Geronimo Powder Company, Riss Truck Lines, Union Wire Rope Co., and Ready-made Homes utilized warehouses and facilities on the plant grounds.

In August 1963, the Army changed the plant’s name to Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant. By August 1965, with the conflict in Vietnam increasing in intensity, the government announced that the Sunflower plant would be reactivated. Shortly after the announcement, 10,000 applications were made for the estimated 2,500 job openings, of which more than half were from former employees of SOW. During the Vietnam War, employment at the plant peaked at 4,065 employees.

During the Vietnam War, the plant produced more than 145 million pounds of propellants before ceasing operations in June 1971. In 1972, the plant was returned to standby status.

In 1971, Sunflower Village owner Louis Ensley sold the property to Kansas City developer Paul Hansen who embarked on the most extensive remodeling of the property’s history. In addition to remodeling the housing units, Hansen worked on the grounds and the surrounding lakes.

To change the community’s image, he began to enlarge the apartments, expanding kitchens and bathrooms, thereby reducing the number of bedrooms in some units. He also added garages to some of the housing and converted some buildings into storage units made available to residents. These changes, along with construction, reduced the village from a population of 1,800 to 1,100 during his first two years of ownership. In the meantime, Sunflower Village had been renamed Clearview City. Hansen then decided to convert Sunflower Village to a retirement village, and by the fall of 1975, he was leasing exclusively to seniors.

At some point, the post office reopened and was renamed Clearview City in 1975.

During the 1970s, the Commercial Center included a grocery store, post office, Savings & Loan office, a restaurant, laundry, arts & crafts shop, and a beauty shop.

In 1981, Paul Hansen died, and his family managed the property for a short time but it was ultimately sold by his estate.

After years of planning, extensive modernization was made at the Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant to produce a component for tank and artillery ammunition called nitroguanidine. The first facility of its kind in North America, production began in 1984 and continued until 1992.

At that time, most workers were laid off except for some tasked with cleaning, repairing, decontaminating, and preserving the equipment for possible reactivation. Controlled burns eliminated many unused structures in 1997. In 1998, after 55 years of operation, the Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant was declared excess property and sold.

In its wake, the plant left a toxic wasteland.

In the meantime, the village was sold to Jim Bush in 1988 and was reverted to general rentals for all ages and families. It was sold again to David Rhodes of Clearview Village Inc. in 2001. That year, Clearview City was annexed by the City of De Soto.

In the subsequent decades following the plant’s final closure, developers promised to clean up the land for various endeavors, including a bioscience lab, shops and homes, an extension of the Shawnee Indian Reservation, and even a Wizard of Oz theme park and resort. However, these plans were waylaid by the costs of cleaning up the toxic land.

In 2005, Sunflower Redevelopment stated that it expected to complete the clean up within ten years, and the Army awarded a $109 million grant for that purpose. However, workers found far more contaminants than expected, and the money was gone by 2010 with plenty of work remaining.

After five years of inactivity, the Army agreed to take over the cleanup in 2015, and three years later, said some of the lands could be ready for development in 2021 or 2022. However, after spending $200 million and completing much work, such as digging up sewer lines, removing contaminated foundations, and trucking out loads of unsafe soil, it was still not complete, and in 2020 the target completion date was pushed back to 2028.

Then in the summer of 2022, the state of Kansas and Panasonic announced that the company would build a $4 Billion EV Battery plant on the Sunflower site. Questions about the cleanup and what the Battery plant could do to the environment were an immediate concern to nearby residents, and residents in Desoto, while feeling hopeful about the future, were also concerned about infrastructure to handle the thousands of employees expected to be hired. However, with the plant being located between Lawrence and Kansas City, it is expected that many of the new hires will commute.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Sources:

National Register of Historic Places

Kansas City Public Library

Post, Chris; Geography Department, University of Kansas

Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant, Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, 1984.

Wikipedia

KCUR/NPR