Pittsburg, Kansas, in Crawford County, is located in the southeast part of the state near the Missouri state border. It is the most populous city in Crawford County and southeast Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the population was 20,646, its peak population to date. Pittsburg sits in the Ozark Highlands region, a mix of prairie and forests. The city has a total area of 12.90 square miles, of which 12.80 square miles is land and 0.10 square miles is water. It is the home of Pittsburg State University.

6th Kansas Cavalry.

On October 23, 1864, a wagon train of refugees arrived in the area from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Troops escorted it from the 6th Kansas Cavalry under the command of Colonel William Campbell. These were local men from Cherokee, Crawford, and Bourbon Counties. Their enlistment was over, and they were on their way to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to be dismissed from service. They ran into the 1st Indian Brigade led by Major Andrew Jackson Piercy near the Pittsburg area. They continued north when a small group of wagons broke away in an unsuccessful rush to safety. The Confederate troops caught up with them and burned the wagons. The death toll was three Union soldiers and 13 civilian men who had been with the wagon train. It was likely that one of the Confederates had also been killed. A granite marker memorial for the “Cow Creek Skirmish” was placed near the Crawford County Historical Museum on October 30, 2011.

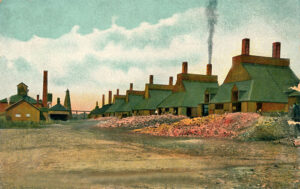

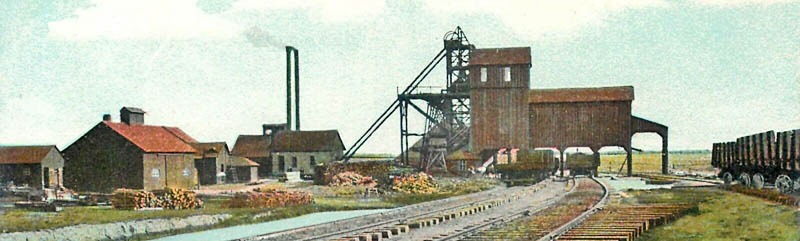

The first coal shaft in southeast Kansas was sunk by the Scammon Brothers just north of Scammon in Cherokee County in 1874. A year or two later, shafts were sunk in the Pittsburg District.

In the winter of 1875, John B. Sargent and E.R. Moffett, both of Joplin, Missouri, conceived the plan of building a railroad from Joplin to Girard, Kansas. These gentlemen were engaged in lead and zinc mining and were seeking an outlet for the products of their mines and smelters. In the spring of 1876, work began, and by the fall of that year, grading reached the vicinity of Pittsburg.

In the spring of 1876, Colonel Ed. H. Brown, who was in charge of the construction of the Joplin & Girard Railroad and worked in the interest of Moffett & Sargent, completed the line to connect the growing lead furnaces of the city to the Kansas coal fields. A second railroad to Pittsburg, Kansas, was completed and celebrated on July 4, 1876, with a golden spike driven into the earth at the Joplin depot.

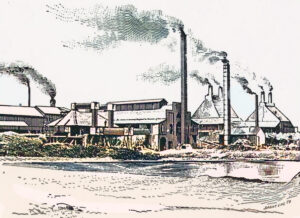

Pittsburg, Kansas Coal Mine.

A 160-acre townsite was laid out on the old settlement of Hopefield. Broadway and Fourth Streets were graded, each one-half mile, and 40 acres from each of the four sections constituted the townsite, on land owned by the Kansas City, Fort Scott, and Gulf Railroad. One tract lay in the immediate vicinity of the townsite, and the other was a short distance away. Both tracts comprised an area of 25,000 acres.

The Town Company was composed of C.M. Condon, President, and B.F. Hobart, who became the owner of the townsite. These parties also included the Oswego Coal Company and were engaged in developing the coal interests. Subsequently, they sold about 55% of the stock to the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway, and a new coal company was organized under the name of the Rogers Coal Company. The company’s capital stock was $200,000, and its operations included two shafts, with production of about 50 cars of coal per day, employing a force of 400 men. The sale of coal was confined mainly to points along the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway in Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas.

St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad

The company had a large number of lots for sale at prices that varied by quality and location. Business lots with 170 feet of depth range from $8 to $24 per front foot; residence lots vary in price by size and location, from $100 to $225 per lot.

When the townsite was laid out, there was only one building on it, owned by Jacob Pugh. It was moved away on June 5, 1876. G.W. Seabury & Co. built the first business house, a one-story frame house 20 feet square, in which they put a general stock of merchandise. J.T. Roach built the first dwelling in July 1876. Another building was constructed at the corner of Fourth and Broadway Streets and was put up for George E. Richey, who occupied it as a drug store.

The town was named after Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and was first called “New Pittsburg.” A post office was established on August 28, 1876, with George Richey as the postmaster.

From the time the town was laid out until October 1876, its population increased to about 100. At that time, it contained three stores, two blacksmith and wagon shops, a hotel, and a post office.

The first general store was built by W.G. Seabury in the winter of 1876-1877 and was occupied with a small stock of goods in the spring of 1876-1877.

A two-story frame schoolhouse was erected in the summer of 1877. The school, which contained two departments, began in the fall with A.J. Georgia was the teacher. Its first attendance was 40 students.

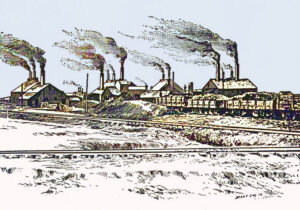

In the spring of 1878, Robert Lanyon, who was from Peoria, Illinois, began looking for a suitable location for a zinc smelter. After looking over the zinc fields around Joplin and the coal fields around Pittsburg, Lanyon chose Pittsburg due to its cheap and abundant fuel. Lanyon located his smelter in the eastern part of Pittsburg and began the construction of the plant.

“The oven for cooking the ore is being laid up and will soon be ready. Two furnaces will be put in operation, and two more will be built. Mr. Lanyon says he thinks he will have one furnace in operation by the first week in June. It is expected that the Lanyon smelter will produce about twelve tons per day, and from five to 30 hands will be employed.”

— The Girard Press

Robert Lanyon Zinc Works in Pittsburg, Kansas.

The plant was soon completed, and during August, seven cars of zinc were shipped. The Robert Lanyon smelter was a success and established Pittsburg as a suitable place for large-scale smelting operations. By the end of two years, this pioneer smelter and a companion plant at Weir City, eleven miles away, were doing a large volume of business. By 1880, they were the only smelters in Kansas. They employed 18 men, with a payroll of $110,000, and produced spelter worth $254,000.

In 1879, two miners from Joplin made the first commercial attempts to mine near Broadway Street. In June 1879, L.C. Hitchcock established the first newspaper, the Pittsburg Exponent.

New Pittsburg was incorporated that year as a city of the third class in the fall of 1879. The first officers were Mayor M.M. Snow and councilmen J.R. Lindburg, W. McBride, F. Kalwitz, P.A. Shield, and D.S. Miller.

Early Pittsburg was rowdy, in part due to the railroads bringing prosperity and problems to the region. Early in Pittsburg’s history, an ordinance for “persons disturbing the quiet” was enacted. Liquor and drunks were also a problem, so the city began licensing and regulating the sale of “spirituous and malt” liquors. On “payroll” days, when coal miners with pockets full of money came to Pittsburg, horse-drawn hacks were very aggressive in their pursuit of business, and often, marshals had to mediate disputes and quell fights among the hack drivers and drunks alike. Most arrests during those days were for being drunk and fighting.

In the spring of 1880, the Granby Mining and Smelting Company began erecting zinc works on the west side of Broadway, north of town.

In the summer of 1880, the Joplin & Girard Railroad was sold to the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad Company for $300,000, and the land owned by Moffett & Sargent was sold to the Pittsburg Town Company for $50,000. At the same time, the schools were graded and comprised three departments. Though the city’s school population was 850, the attendance was about 600.

The Methodist Episcopal Church was the first to build a house of worship in 1880. The brick building stood on the corner of Fifth and Pine Streets. After selling their church building to the Presbyterians, the trustees of the Methodist Episcopal Church built a larger one on the corner of Eighth and Locust Streets in 1891. The next was a Christian Church across Pine Street from the United Presbyterian Church. The Baptists built a small brick church on Walnut near Fifth Street, which they sold to the German Methodists. Later, they built a fine church building at the corner of Seventh and Walnut.

The success of the Robert Lanyon smelter soon brought other smelters to Pittsburg. In 1881, the firms of S.H. Lanyon and Brother and W. and J. Lanyon came. Each organization constructed a plant with an approximate eight-ton daily capacity.

In 1881, H. C. Bruner built the first flouring mill on East Fourth Street. The Pittsburg Exponent newspaper was sold to the Flint Brothers of Girard, Kansas, who began publishing the Pittsburg Smelter in March 1881. That year, on June 1, 1881, the city’s name was officially changed from New Pittsburg to Pittsburg.

In the early 1880s, Pittsburg had several churches, including Methodist, Episcopal, Christian, Catholic, and Baptist. Only the Methodist and Episcopal denominations had buildings. The Methodist Church was a neat brick structure, and the Episcopal Church was a small frame building. The town also boasted eight general stores, one grocery, three hardware stores, four drug stores, two shoe stores, one clothing store, four meat markets, two shoe shops, two blacksmith shops, three millinery stores, one furniture store, three lumber yards, six hotels, one merchant tailor, two livery stables, and a harness shop.

A second school building—a one-story frame structure—was built that year. Afterward, the school was divided into four departments, under the charge of D. Hollinger, Principal, and Miss Ida Bromback, Miss Cora Edson, and Mrs. James Officer, teachers.

In 1882, the Granby Mining and Smelting Company, with mines at Joplin, built a smelter in the north part of Pittsburg. At that time, William and Josiah Lanyon came from Mineral Point, Wisconsin, and built extensive zinc works. The addition of smelting works to the coal mining gave Pittsburg a significant impetus, and new business enterprises of all kinds came in. These were followed by two other plants, the St. Louis and the Wear. Then, Pittsburg was known as the coal and smelting city. The smelters ran practically all the time, on nights, Sundays, and weekdays. Shutdowns were infrequent.

In the fall of 1882, the Cherryvale Division of the Kansas City, Fort Scott, and Gulf Railroad was constructed through the town.

In the summer of 1883, four brick business houses were built. John R. Lindburg built on the corner of Fourth and Broadway, Brown & Brown on the next block south, and I.P. Waskey built across the street.

The Pittsburg & Midway Coal Company was founded in 1885. Midway referred to a coal camp in eastern Crawford County that was “midway” between Baxter Springs, Kansas, and Fort Scott, Kansas. It was one of the oldest continuously running coal companies in the United States. After the Kansas mines closed, its headquarters moved to Denver, Colorado. In September 2007, Chevron, which owned the company, merged it with its Molycorp Inc. coal-mining division to form Chevron Mining, thus ending the Pittsburg corporate name.

In 1887, a coal shaft was sunk on the Pittsburg townsite and one on Carbon Creek, a few miles northeast of Pittsburg.

In 1888, Lewis Hull and T.G. Dillon started a small packing plant, which grew quickly. This enterprise began when Lewis Hull opened a meat shop, selling sausage, bologna, and other smoked meats that were shipped in from Kansas City. Seeking to increase his earnings by smoking his own meats, he expanded his business to the point where he needed to secure larger quarters. At this time, he was joined by his brother-in-law, Thomas Dillon. In 1891, Hull and Dillon built a new packing plant on the banks of Cow Creek west of the city. It was enlarged several times over the next few years.

In 1890, Pittsburg’s population was 6,697. This increase was due to jobs created by coal mining and the railroad. At that time, 11,835 miners were employed by 55 different coal companies. That year, the Hotel Stilwell was erected. One of the finest hotels in the West, it was kept by O.K. Dean, who catered bountifully to the needs of his guests. The Hotel Stilwell was built in a prime location on the northern edge of Pittsburg’s downtown district, on the northwest corner of Seventh Street and Broadway, the city’s major north-south commercial street. Today, the building still stands, serving as the Stilwell Apartments.

Other hotels included the Crescent on the corner of Third and Locust; the Commercial at Third and Broadway; the Phoenix at Fifth and Locust; and smaller ones scattered across the city.

In the fall of 1890, Robert Nesch and John Moore came from Atchison. They embarked in the brick business, manufacturing, building, and paving brick, which, proving of an excellent quality, a contract was entered into with the city, by which they were to pave Broadway for a distance of three-fourths of a mile. During this time, Mr. Moore retired, leaving Mr. Nesch in complete control of the brick plant, which has grown to large proportions. The excellent quality of the clays found in and around Pittsburg attracted the attention of manufacturers. Now, two other clay-working establishments are engaged in manufacturing. One turns out brick to be used exclusively in building tall smoke-stacks for manufacturing plants; the other makes drain and sewer tile, hollow blocks for building, and other products.

Pittsburg also had a silver smelter for a few years. During the summer of 1890, some men looking for a suitable place to locate a silver smelter visited the city. They were attracted by cheap coal and the citizens’ desire for additional industrial plants. After looking the field over, they decided to establish a plant. After a few days of negotiations between the visitors and the Pittsburg Commercial Club, an agreement was reached, and a formal contract was signed. This agreement between the Pittsburg Commercial Club and the Short Method Refining Company of Pittsburg provided that the smelter company should refine not less than 20 tons of refractory ores at Pittsburg daily for three years and that the Commercial Club would erect a suitable building on a five-acre tract and supply $2,000 for the construction of furnaces. In addition, the smelter company agreed to install machinery for $16,000. The plant was put into operation until September 1891. The silver smelter operated at a profit for four years.

Looking North on Broadway in Pittsburg, Kansas.

In 1891, there were 29 corporations doing business in Pittsburg with a combined capitalization of nearly $10,000,000.

In 1892, Pittsburg was advanced to a city of the second class.

During the early 1890s, Pittsburg’s zinc smelters reached their greatest output. In 1893, there were 25 active zinc smelters in the United States, nine of which were in Kansas. Of these, six were located in Pittsburg. However, Pittsburg did not remain the leading smelter-producing city for long.

On March 6, 1894, the town’s name changed from New Pittsburg to Pittsburg.

By the mid-1890s, the natural gas fields of southeast Kansas were being developed rapidly. These gas fields offered a fuel cheaper than coal. This played havoc with the zinc smelters and with some other industries in the coal fields. Pittsburg began to lose its smelters. Soon, all but two were gone. These two, the St. Louis & Pittsburg and the Cockerill smelters, continued to operate on coal for a time. Soon, they were forced to close because they could not compete. The closing of the zinc smelters was a severe blow to Pittsburg. It was followed by a loss of about 2,500 people and a payroll of approximately $25,000 a month.

In 1898, 53 mines were operating in Crawford County. Of these, approximately 30 were within five miles of Pittsburg, and 17 were within 2.5 miles of the center of town. At that time, Crawford and Cherokee Counties were the leading coal-producing sections of the state. Of the two, Crawford County was by far the largest producer.

In 1900, Pittsburg had grown to 10,112 people. At that time, it was the most heavily unionized city in Kansas. In addition to some coal mining, the city’s economic base was industry.

By that time, because of the abundance of cheap gas and improvements in gas smelting furnaces, all the smelters in Pittsburg were closed. Within a couple of years, so many businesses were using gas in Iola that the pressure became so severe that the smelters had trouble even firing up, let alone running at full capacity. That, coupled with the rise in zinc prices, led to the reopening of coal-fired smelters like the East Smelter and the North Smelter in Pittsburg by the Lanyon Zinc Co. and Cockerill-Zinc Company.

Pittsburg State University was founded in 1903 as a normal training institution. Over the years, the college diversified its aims and goals, becoming a multipurpose institution. It has always had a strong manual and industrial arts program and has trained many of the area’s public and private school teachers.

In 1904, 55 coal companies employed 11,835 men, in addition to many small operators, and 44 new coal mines were opened. During that year, about 700 new dwelling houses were built, and $3,000,000 was spent on public improvements.

That year, the Cherokee-Lanyon Smelter Co. sold the North Smelter to local businessmen J.D. Smith and C.A. Miller.

In 1905, the City of Pittsburg attained the rank of first class.

Smith and Miller sold their Smelter to the Pittsburg Mining and Smelting Co., which reopened the facility with ten furnaces. The North works were operated by the Cockerill-Zinc Co., the outcome of a merger in 1908 of several smelter works in Southeast Kansas. At one time, the Cockerill-Zinc Co. operated both the North and East Smelters.

Coal mining in the Pittsburg-Weir Coalfield had its peak activity between 1890 and 1910.

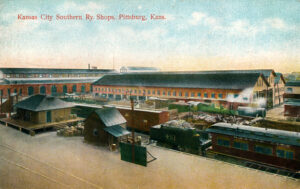

In 1910, Pittsburg was at the junction of four railway systems — the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, the Missouri Pacific Railroad, the Kansas City Southern, and the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad. The main shops of the Kansas City Southern were located here and employed 1,600 men. It was in the mineral and oil district, and the zinc smelters employed 1,200 people. Coal was extensively mined and shipped. Other important industries included foundries and machine shops; cornice works; flour and planing mills; a tent and awning factory; and boiler works and a paving and building brick plant. Sewer pipe works factories for the manufacture of gloves, mittens, garments, and cigars, stone quarries, and packing houses. There were four banks, four newspapers — the Headlight, the Kansan, the Labor Herald, and the Volkesfreund, and a monthly fraternal paper called the Cyclone. The city had electric lights, fire and police departments, a sewer system, waterworks, paved streets, an electric street railway, a $60,000 opera house, a fine school, and church buildings. It was the seat of the manual training branch of the state normal school, a Catholic Academy, and a German Lutheran school. There were telegraph and express offices and an international money order post office with eight rural routes that the government designated for a postal savings bank. The population at that time was 14,755.

Pittsburg had grown from a plot of bare prairie to a city of almost 15,000 inhabitants, with all the modern conveniences. Five railroads carried her commerce. Four wells, reaching depths of 1,200 to 1,500 feet, provided an abundance of pure water. The trolley cars of the Pittsburg Railroad Company, extending to Frontenac on the northeast and Chicopee on the Southwest, making a continuous line of ten miles, furnished the transportation to the people; while the railroad shops of the Kansas City Southern Railway, with the many other manufacturing establishments, furnished employment to her people.

The need for zinc increased during the run-up to World War I, so the old smelters in Pittsburg were once again reopened, the East Smelter by the Pittsburg Zinc Co. and the North Smelter by the Joplin Ore and Spelter Co. in 1915. Business was profitable because the price of zinc continued to rise during the war.

In 1914, the St. Louis & Pittsburg and the Cockerill smelters began operating again due to great demand. However, by 1917, the price plummeted, and the Pittsburg smelters closed once again. The property of the smelter works in the Pittsburg area began being dismantled, and the buildings were destroyed. The North Smelter was the last one to be torn down in 1921.

Smelting operations were a dirty business, contaminating the surrounding land with high levels of lead, sulfur, cadmium, and arsenic, leaving the area barren and with very little vegetation. Some of these areas have been cleaned up through million-dollar initiatives, in which contamination has been contained or removed and, in some cases, covered with concrete and asphalt. One of these areas in Pittsburg is where the Weir City Zinc Smelter was in the vicinity of 28th and North Broadway.

The population around the coalfield peaked at 90,000 in 1920, but fewer workers were needed as safer, more efficient surface mining with machines replaced shaft mining.

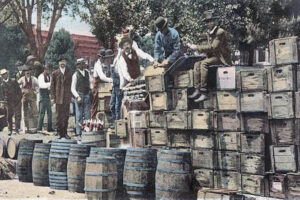

U.S. Prohibition began in 1920, coinciding with the rise in demand for workers in Southeast Kansas coal mines. Miners were underpaid, easily replaced, and had no health insurance. If they lost their jobs, there was no unemployment program. Because many of them were immigrants, they had few advocates. These “foreign elements” turned to bootlegging in a desperate attempt to feed their families. Many bootlegged wine and “deep shaft whiskey,” delivering it as far east as New York City.

One Pittsburg factory was said to have produced 210 gallons of liquor per day, which netted the owners $18,000 in only two weeks of operation.

The illegal bootlegging industry of Crawford and Cherokee Counties was so strong that President Herbert Hoover’s Wickersham Commission, appointed to study prohibition enforcement, specifically mentioned the two counties. Not surprisingly, the report declared these counties two of the four worst statewide in prohibition compliance.

These were families who had escaped escalating violence in Europe. They knew they were breaking the law, and they didn’t care. They were trying to survive. People said, ‘It may have been illegal, but it wasn’t wrong,’”

Miners worked long, hard hours. Deep shaft mining was deadly work, and the pay was low. Injuries and deaths occurred underground because of explosions and cave-ins. There was no workers’ compensation or unemployment benefits. Plus, when Winter ended, the need for coal decreased, and the number of jobless people increased. When they had leisure time, they flocked to sporting events, and lakes were eventually built just for recreation. Nearly every coal camp had an opera house to entertain miners with live performances.

The area soon became a hotbed for worker rights. The small town of Girard was home to the state’s busiest post office at the time because the largest socialist newspaper in the nation was published there. In December 1921, a march and protest that closed mines made national headlines. It had been made illegal for the men to protest, so mothers, sisters, wives, and sweethearts protested the working conditions of their loved ones. Thousands marched for three days. The governor and state guard were called in to help. National newspapers dubbed them “The Amazon Army.”

In 1928, the citizens of Pittsburg purchased 400 acres, 80% of which were old strip pits, and presented the tract to the state of Kansas. This became Crawford County State Park. It is a rugged, well-timbered park through which wind many beautiful, narrow lakes. Since taking it over, the state has improved it significantly and converted it into a pleasant recreation center.

Between 1925 and 1930, combustion engineers made significant progress for the mining industry, increasing production by about 35%.

In 1930, daily production in the large mines ran as high as 1,500 tons.

In 1931, mechanized strip mining overtook underground mining in output, and that, combined with competition from eastern coal, decreased underground mining’s importance in the region. The decline had a debilitating effect on many mining communities and their inhabitants. Miners and dependents departed, and most camps were moved or fell into physical decay.

Most of the coal camps were dismantled by the 1930s or 1940s.

After World War II, production in the Tri-State mining district gradually declined.

With the cessation of the last shaft mine in the coal field in April 1960, a colorful and important era of mining ended, which had a profound impact upon the history of this portion of southeastern Kansas. The last active mine in the Tri-State Mining District, located two miles west of Baxter Springs, shut down in 1970 due to economic and environmental problems. This ended a century of lead and zinc mining in the Tri-State.

Today, nature has converted the last runs of the shovels into lakes, many of which have been stocked with fish through natural processes. These man-made lakes quickly became prime outdoor recreation areas for camping, fishing, hiking, hunting, and, increasingly, mountain biking and kayaking.

Big Brutus, a 16-story power shovel, is a memorial to the Pittsburg & Midway Coal Company’s operations in West Mineral, Kansas.

Pittsburg is 11 miles southeast of Girard, the county seat, three miles from the Missouri state line, and 124 miles from Kansas City,

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated February 2026.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Explore Crawford County

Home Authors; A Twentieth Century History and Biographical Record of Crawford County, KS, Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, 1905

Kansapedia

Industrial History of Pittsburg, Kansas, Kansas Historical Society

Pittsburg Chamber

Pittsburg Memories

Wikipedia