Flush, Kansas, is an unincorporated extinct town in Pottawatomie Township of Pottawatomie County.

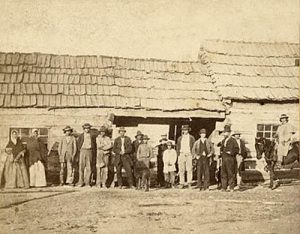

Volga Germans from Bavaria first inhabited this community and traveled so far to escape the horrific famine, depression, and heavy taxation plaguing their homeland.

Thanks to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, they were promised affordable land and arrived in 1854. They found their resting spot in a fertile valley far enough away from the violence of Bleeding Kansas. Fortunately, they were only a few miles northwest of the St. Mary’s Indian Mission.

When they traveled through the St. Mary’s Indian Mission to Rock Creek Valley, they stopped to talk to the Jesuit Fathers and were glad to see some form of Catholic life in this part of Kansas. However, the Jesuit Fathers told them that there were only a few priests there at that time and that they were there to care for the Indians. Therefore, they said, it would not be possible for a Missionary Father to visit them very often.

As soon as the early settlers had staked their claims and built their log cabins in the fall of 1854, they returned to St. Mary’s as often as possible to attend Mass.

Almost a year passed after the arrival of the early settlers before the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was offered in Rock Creek Valley. With all the community’s settlers present, Mass was offered in a log cabin on the Michael Repp farm by Father Schultz, Superior of the St. Mary’s Indian Mission. After Mass was over, two children were baptized.

Since Rock Creek Valley was far from St. Mary’s Indian Mission, Father Schultz agreed to come to say Mass once every three months. A little later on, as the community grew, he agreed to say Mass once a month.

By 1859, there were three resident priests at St. Mary’s, one of whom was there to serve the white settlers. Father Louis Dumortier’s task was to ride out on horseback and search out the Catholic families in the outlying districts. At first, he came to say Mass at Flush once every two weeks, but it was not long until he said Mass here every Sunday in the homes of Michael Repp, Michael Floersch, and Franz Anton Dekat.

The church opened a parish school in the 1890s.

Flush derived its name from Michael Floersch, a pioneer settler. When the post office was opened on June 20, 1899, the postmaster-general could not pronounce Floersch and changed the name to Flush.

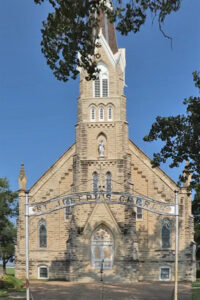

Construction on the St. Joseph’s Catholic Church began after a solemn Mass in honor of St. Joseph on June 3, 1901. The cornerstone was laid on November 28, 1901.

Henry Floersch built the Flush Store in 1903 across the street from St. Joseph’s Church. The Flush Store also served as the U.S. Post Office for Flush area residents. This building still stands today in the Prairie Town Village, Wamego Historical Society and Museum, in Wamego, Kansas.

A railroad expansion through Flush in 1908 poised the town for increased growth. From 1909 to 1914 were the fundamental formative years that would determine the future of Flush.

In 1910, Flush had a local telephone exchange, a money order post office with one rural route, and a population of 23.

In 1912, Father Heer began developing a means to have railway access in Flush. Soon, 129 community members signed a petition for the Wamego and Rock Creek Valley Railroad to come through.Flush. That year, the town founders drew up a plat for the community, expecting a boom from the railway.

The Floersch family constructed a grain mill with a train depot to serve the railroad.

A $500 payment per 80-acre tract of land was to be paid to those who would lose land to the railway, but the money had to be raised by the community’s people. However, this proved to be a minimal source of income.

The railway started digging the trenches for the rocks and tracks to be laid. However, the citizens didn’t raise enough funds, and the railroad fell through in 1914. With the railroad’s failure, the Town of Flush became an unrealized dream, and many residents departed for other communities.

The church maintained German-speaking priests until 1927. That year, the post office closed on November 30.

The parish school ceased operation in 1976.

The Rock Creek High School was built one mile north of Flush in 1991.

Today, all that remains of the community is the St. Joseph’s Catholic Church campus, which includes a rectory, parish hall, and cemetery.

Flush and the St. Joseph Church community are recognized around the region for the annual Flush Picnic, a fried chicken dinner fundraiser and fair that benefits the church community. The picnic draws crowds of over 2,000 people to Flush and is typically held on the last Wednesday in July every year.

The community is served by Rock Creek USD 323 public school district, located one mile north of Flush.

Flush is located on Flush Road, which intersects with Route 40 between Manhattan and Wamego, nine miles southwest of Westmoreland and eight miles from St. George.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, October 2024.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Pottawatomie County

Pottawatomie County Photo Gallery

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912

Dunham, Tim; Lost Kansas Communities; Dr. M.J. Morgan Chapman Center for Rural Studies; May 5, 2011.

Flush Homestead

Independence Daily Reporter

Wikipedia