Kansas Governor Wilson Shannon

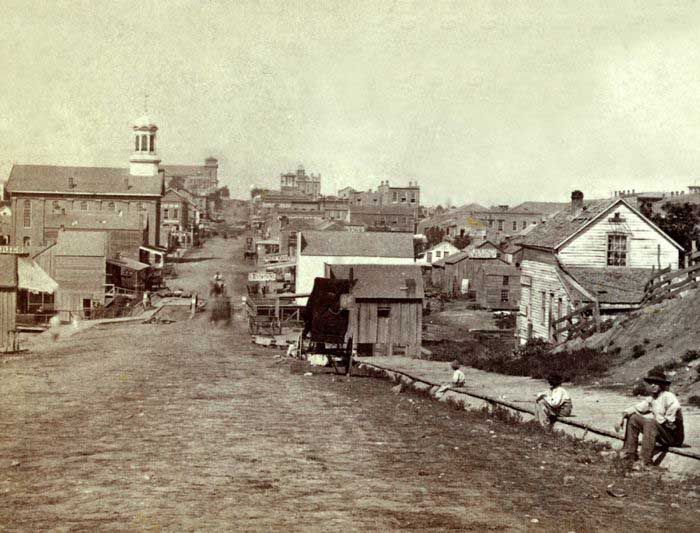

In October 1855, a Constitutional Convention was held in Topeka, Kansas, by Free-Staters seeking to subvert the official pro-slavery territorial legislature. The “official” territorial legislature, called the “Bogus Legislature,” had been elected in March 1855 and suffered widely from electoral fraud. At the Topeka Constitutional Convention, the Free-Staters developed the first Kansas constitution, which Free-State voters approved in Kansas on December 15, 1855. This document banned slavery in the state.

However, several pro-slavery advocates had settled in Leavenworth, and just a week after the Constitutional Convention at Topeka had adjourned, a large pro-slavery meeting was held in the city on November 14, 1855. It was the occasion of Governor Wilson Shannon’s first visit to Leavenworth.

Shannon, who served as the second governor of Kansas Territory, was appointed to the office by President Franklin Pierce and became governor on September 7, 1855. Shannon was known for his Southern sympathies, so much so that a contemporary described him as “an extreme Southern man in politics, of the “border ruffian type.”

When Governor Shannon arrived, he was met by a committee of Leavenworth citizens before being escorted to the meeting, held in Alexander’s stone building at the southwest corner of Main and Shawnee Streets. The group elected the governor as the chairman of the meeting, who opened the meeting by denouncing the Topeka Constitution and the Free-State movement generally. Others also made speeches, including General John Calhoun, Surveyor General of Kansas and Nebraska Territories, who talked long and bitterly against the Free-Soilers. The only Free-State speaker who asked to be heard was a man named Marc Parrott, whose speech could not be heard over the crowd’s hoots, hollers, and jests.

A week later, the Free-Staters of Leavenworth held their meeting, and politics in the town were boiling. In the Wakarusa River Valley near Lawrence, Kansas, a confrontation known as the Wakarusa War erupted between the two factions. On December 1, 1855,

Brigadier General Lucian J. Eastin, of the Second Brigade of Kansas Militia and editor of the Kansas Herald in Leavenworth, ordered his troops to concentrate in the city “to march at once to the scene of the rebellion” and to put down the 1,000 outlaws of Douglas County. Easily, this might have made Leavenworth a portentous seat of war. However, only about 100 men assembled in Leavenworth, with about 30 more enlisting. However, many of the potential invading armies were from Missouri. The invasion, however, was stalled when Governor Shannon ordered the troops disbanded.

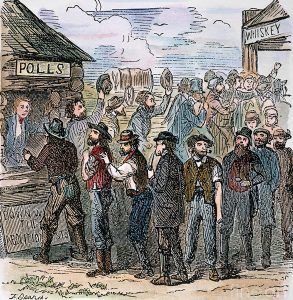

At a State Convention held in Lawrence on December 22, 1855, two Free-State men from Leavenworth were chosen for high positions. Mark W. Delahay was chosen as the Congressional nominee, and H. Miles Moore was the candidate for Attorney General. The election was scheduled to be held on January 15, 1856. However, the pro-slavery element was so strong in Leavenworth that the more timid Free-State citizens hesitated about holding the election for State and county officers. Several days before the election was to take place, a few weak hearts met and resolved that one should not be held. In the meantime, the Free-State Mayor Thomas T. Slocum resigned on January 8, 1856, causing considerable excitement and some indignation. George Russell also resigned as Councilman and the seat of J. H. McClelland became vacant because he persistently absented himself. They were all Free-State men and found their duties too difficult in these pro-slavery times. The day before the election, J. H. Day, President of the City Council, issued a municipal order forbidding it to take place. No polls were opened; however, an old stocking was presented to Free-State voters. In the end, the election did take place, though not in any regular fashion. The newly elected mayor was a strong pro-slavery man named William E. Murphy.

Meanwhile, Leavenworth wasn’t the only city in Leavenworth County that struggled between slavery advocates and abolitionists. At nearby Easton, some ten miles to the northwest, an attack was made upon the polls, which were so vigorously defended by Free-State voters, commanded by Stephen Sparks of Alexandria Township, that a pro-slavery man named Mr. Cook was mortally wounded. Several fights occurred in which the pro-slavery men were generally put down.

Among the Leavenworth people who attended the election at Easton to see that the voting was fairly conducted and who assisted in defending the polls were Captain R. P. Brown, member-elect of the Legislature, Henry J. Adams, senator-elect, J. C. Green, Joseph H. Byrd, and two or three others. The next morning, as they were returning in a wagon to Leavenworth, they were met by a company of Kickapoo Rangers about halfway to their destination. Led by pro-slavery Captain Martin, some 50 troops were on their way from Leavenworth to Easton to avenge the treatment of their pro-slavery friends and the death of Mr. Cook.

The Free-Staters from the Leavenworth party were made prisoners, turned back to Easton, and confined in a store where a noisy, drunken crowd of pro-slavery soldiers guarded them. The troops’ spite was mainly concentrated on Captain R.P. Brown, many of them having known him and learned to fear him in Leavenworth.

Finally, the drunken soldiers managed to get him into an adjoining building and organized a court for his trial. Though pro-slavery Captain Martin tried to control the men, he could not. However, he did allow all but Captain R.P. Brown to escape. While Brown was being questioned in the mock trial, many drunken soldiers became impatient, broke up the “court,” and took Captain Brown out of the building, pummeling him along the way. After striking Brown on the head with a hatchet, the nearly dead man was taken to his home in a wagon. Before Brown died, he could only say to his wife, “I am murdered by a set of cowards.” He was buried on Pilot Knob the next day.

Thomas A. Minard of Easton, at whose house the election was held, narrowly escaped injury at the hands of a mob a few days later. However, he barricaded his doors and lived to be elected Speaker of the Free-State Assembly, which convened on March 4, 1856, in Topeka, Kansas. Also occurring during this meeting of the Free-State legislature, Charles L. Robinson was elected as territorial governor, which enraged President Franklin Pierce, who called the Free-State Legislature unlawful and called for the arrest of its leaders. Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones recorded the names of every member of the Free-State government, and many assumed they would soon be arrested for treason. This would happen later during and immediately following the Sacking of Lawrence.

In the meantime, the Topeka government sent James H. Lane to Washington with a petition to the U.S. Congress asking for the admission of Kansas into the Union as a Free State. The documents contained many irregularities, and the debate in Congress was heated. Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas attacked the petition as fraudulent. Senator William Seward argued in support of admitting Kansas as a Free State. The debate was so virulent that James Lane went so far as to challenge Senator Douglas to a duel. Douglas refused to accept the challenge.

David Rice Atchison

With the president’s support, General David Rice Atchison and other pro-slavery leaders determined that “Free-soilism” should be eradicated at all costs. The President sent additional Federal troops to Fort Leavenworth to enforce his demands.

Hordes of men from Missouri began to march through the Territory of Kansas to Topeka, sweeping away from their path every vestige of “Free-soilism” and relentlessly persecuting Free-State men. In April, the main target was Charles L. Robinson, who soon escaped to Missouri.

He was arrested at Lexington, Missouri, in May on the pretext that he was “fleeing from an indictment,” though the indictment for treason had not yet been found against him. He was brought to Leavenworth on May 24, and the indictment was completed. He was held at McCarty’s Hotel as rumors ran rampant that he might be rescued by Free-State friends or hanged by a pro-slavery mob at any time. However, though avid opponents, pro-slavery officials who had him in charge considered that their honor was staked upon his safety. Therefore, General William Richardson, Commander of the Kansas Militia, often stayed in the same room with him while Judge Samuel Lecompte guarded his door.

Upon orders from Governor Shannon, Robinson was removed to Lecompton, the Territorial capital, on June 1. Though the ex-governor was in Lecompton, his attorney, Henry Miles Moore, a resident of Leavenworth, soon became a target for much of the bitter and dangerous feelings of the pro-slavery advocates. In late May, a squad of Kickapoo Rangers invaded his office. Though no violence occurred, they warned Moore that he was making himself too prominent for his safety. The next day, Moore and his partner Marc Parrott were arrested and marched to the warehouse of Russell, Major & Waddell. Other men were also arrested, including the clerk of the Investigating Committee, a Lawrence mail contractor, and Free-State Captain Robert Riddel. As all were confined, a huge crowd gathered outside, demanding that the prisoners should be hanged. The pro-slavery fanatics considered Moore the worst, as he had formerly been a slave owner. All but Moore were released the next day, March 29, promising they would leave the territory. A rush was then made to hang Henry Miles Moore, but Colonel Clarkson, the commander of the city militia, halted it.

Although no further personal demonstrations were made against Moore or the investigating committee, Mayor William Murphy deemed it advisable to call a meeting on May 31, 1856. All citizens were called who were in favor of “sustaining and enforcing the laws of the Territory of Kansas and the Constitution and Union of the United States, and of restoring peace in the community.” A vigilance committee was appointed at the meeting, and a very bitter spirit evinced toward the investigating committee. The gathering was dissolved in confusion, however, by the temerity of Reverend H. P. Johnson, who dared to offer a resolution that “we believe there are a good many Free-State men in the Territory who are good, true and law-abiding men, and would aid in enforcing the laws of the Territory.”

Miles Moore was arrested again on June 4 upon a bench warrant from Judge Lecompte’s court, charged with assuming the office of Attorney General of Kansas’. He was released on bail and ordered to appear in court at Delaware City in August.

Samuel D. Lecompte

In the meantime, the mayor appointed the vigilance committee to “restore peace in the community,” which had been increased to 50 men, and on June 5, several Free-State men were ordered to leave the territory. However, a proclamation by Governor Shannon ordered the disbanding of all Free-State committees organized to drive settlers from the Territory, and the Free-State men were protected.

The Sacking of Lawrence in May 1856, followed by John Brown’s war, the published reports of the investigating committee, General John Whitfield’s marching of troops into Kansas, the report of General James Lane’s advance from the North with his Abolition army, all served to keep alive the hot fires of political feeling and drew on the ruffian element to the commission of bloody crimes. Leavenworth was not exempt. One of the most heathenish atrocities occurred near the south line of the city on August 19, 1856.

A Missouri ruffian named Fugit had bet six dollars against a pair of boots that he would bring Leavenworth an Abolitionist’s scalp in less than two hours. Starting on his inhuman errand, he met a young man named Hoppe, who had just arrived from Illinois a few days ago and was returning from Lawrence, where he had taken his wife to visit a sister. He was shot dead from his carriage by Fugit, who scalped his victim and left him on the road.

Fugit then fled to Missouri with the scalp. In May 1857, he was arrested in Leavenworth, tried for murder, and acquitted! Captain Frederick Emory and his gang of Regulators applaud Fugit’s act, but an innocent German, who expressed horror at the spectacle, was shot himself.

The ruffians of the pro-slavery party had sworn that no Free-State man should travel on the road between Leavenworth and Lawrence. Therefore, Captain A.B. Miller and his gang kept a close watch over the road. A few months after the scalping of Hoppe, his wife, the Unitarian minister of Lawrence, Reverend Nute, and a Lawrence merchant named John Wilder were traveling on the road on August 27, 1856, to obtain provisions at Leavenworth. As they neared the city, they were all taken prisoner by Emory’s gang. Mrs. Hoppe was released and got passage down the river, but the others were held prisoners of war until released by order of Governor John Geary.

Territorial Governor John Geary

A reign of terror had again commenced in Leavenworth. Armed bodies of men were stationed at all points along the river and turned every boat back, which brought suspected Free-State emigrants. Bands of ruffians were also organized, principally in Missouri, to drive away any settlers guilty of Free-State opinions. Among the most noted of these bands was that which ravaged Leavenworth under the command of Captain Frederick Emory, a United States mail contractor. In the name of “law and order,” they entered the houses and stores of Free State people and drove them into the street without regard to age, sex, or previous condition. On Sunday night preceding the election for Mayor, on September 1, 1856, about 40 men went through the city streets crying out for all who would not take up arms to enforce the territorial laws to leave Leavenworth immediately or suffer the consequences.

The next day, after committing many outrages, the Regulators, under Emory, approached the house of William Phillips, a lawyer who, in May 1855, had been tarred and feathered, ridden on a rail, and subjected to other indignities in the streets of Weston, Missouri. However, Phillips wouldn’t be driven out of his home and, standing boldly on his porch, fired upon the ruffians when they drew up in front of it, killing two of them. The gang then directed a volley of bullets at Phillips and the house, riddling him and the house with a leaden storm. Phillips died in the presence of his wife and another lady. His brother, who was with him, had his arm so badly broken with bullets that it had to be amputated.

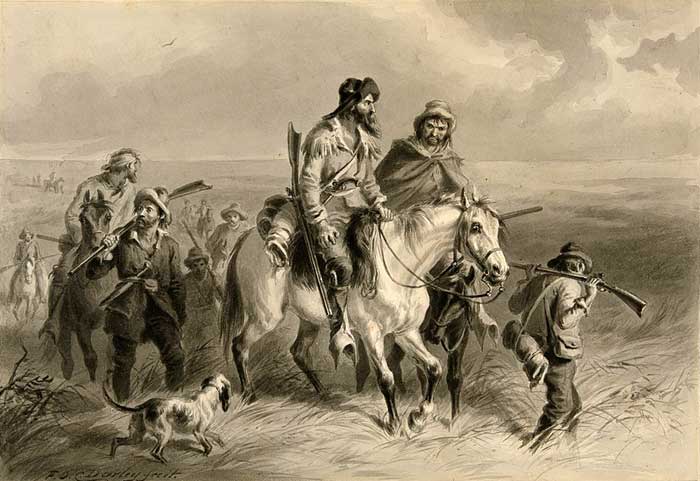

Border Ruffians

For the rest of that day and the next, September 2, Emory and his 800 Regulators paraded the streets of Leavenworth, “collecting” Free-State supporters and shipped about 150 out of the city on two steamers without any provisions. As a result, numerous other citizens fled from the city, some escaping to the fort and placing themselves under the protection of the United States.

The arrival of the new appointee, Governor John Geary, was most opportune, as Captain Emory and his gang held high carnival in and around Leavenworth. They had just captured three Free-State settlers and confiscated their property when the Governor arrived at Fort Leavenworth. On September 9, Captain Emory was captured, his prisoners set free, and he, in turn, was released himself.

The arrival of Governor Geary in the Territory may be said to mark the end of the terrible conflict that had raged in Kansas for two years. Upon his arrival, he addressed a letter to the U.S. Secretary of State, William L. Marcy, which said.

“The town of Leavenworth is now in the hands of armed bodies of men who, having been enrolled as militia, perpetrated outrages of the most atrocious character under the shadow of authority from the Territorial Government. Within a few days, these men have robbed and driven from their homes unoffending citizens, have fired upon and killed others in their own dwellings, and stolen horses and property under the pretense of employing them in the public service. They have seized persons who have committed no offense and, after stripping them of all valuables, placed them on steamers and sent them out of the Territory. Some of these bands, who have thus shamefully violated their rights and privileges and shockingly misused and abused the oldest inhabitants of the Territory, who had settled here with their wives and children, are strangers from distant States, who have no interest in, nor care for, the welfare of Kansas, and contemplate remaining here only so long as opportunities for mischief and plunder exist.”

By October 1856, peace virtually reigned in Leavenworth, the “Regulators” being the last to abandon their organization, and only then did Governor Geary send an order to Mayor Murphy that read:

“I regret to inform you that since the receipt of your letter, I have received numerous complaints from persons claiming to be your citizens. It is said there exists in your city an irresponsible body of persons, unknown to the law, calling themselves ‘Regulators;’ that these persons prowl about your streets at night and warn peaceable citizens ‘to leave the Territory, never to return, or they may be removed when least expected.

This thing, Mr. Mayor, will never do and cannot be tolerated for a single moment. These ‘Regulators’ must be disbanded and leave the government of the city to yourself and the authorities known to the law.”

The Mayor then issued his proclamation, declaring that he would rigidly enforce the law against the outlaws, and the excesses were checked.

Though the deeds of the Leavenworth Regulators had been stopped, animosity and violence would continue in the city periodically over the next few years. In April 1857, Martin Kline was killed by Merrill Smith, the marshal of Leavenworth. James T. Lyle, the City Recorder and pro-slavery advocate was killed by Free-State man William Haller on June 29, 1857, over an argument at the election polls. James Stevens was murdered at Leavenworth on July 31, 1857, by Missouri ruffians John C. Quarles and W. M. Bays. The next day, the citizens hung the murderers to an elm tree near Young’s sawmill.

Fugitive Slave

One of the most famous events occurred in January 1859 when Charley Fisher, a fugitive slave, was captured and liberated. Fisher was employed in the Planters’ House barbershop when a pro-slavery man recognized him and notified his master in Kentucky, who soon arrived to take him back. Fisher was arrested under the Fugitive Slave Law, which quickly raised animosities between the Abolitionists and the Southerners. The Free-State men refused to allow Fisher to be placed in jail pending a hearing before a United States commissioner. After much debate, it was agreed that two Abolitionists and two pro-slavery men should guard Fisher in a fourth-story room in the Planters’ House Hotel until a hearing could be held. However, Fisher was rescued from his strong guard by a party of citizens who believed him to be free. He was not recaptured.

In the end, the Free-Staters prevailed, and Kansas entered the Union as a Free State on January 29, 1861, just a few months before the start of the Civil War.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated March 2024.

Also See: