Hickory Point, Kansas is an extinct town in Jefferson County.

The first settler was Charles Hardt who located in Jefferson Township and started a trading ranch in June 1854.

The community of Hickory Point was laid out in March 1855 on the north side of the Fort Leavenworth–Fort Riley military road. The town was named after a grove of hickory trees. The first post office in the township was established at Hickory Point, and Charles Hardt was appointed postmaster.

From the beginning, a contest arose between the Free-State and pro-slavery residents of the area. Party feelings ran high, and each faction regarded the other as having no rights. At the first election, the pro-slavery men took possession of the polls, and there was little respect for law and order on either side. After the outrages perpetrated at the first election, each party held its own election and refused to acknowledge the other as legal. By the summer of 1856, the Free-State settlers had become the stronger faction and were determined to drive the other party out.

On June 8, 1856, two pro-slavery men, Jones and Fielding, were driven away. At that time, the settlement consisted of three log buildings, a store, a hotel, and a blacksmith shop. Both parties in the neighborhood went armed, and several skirmishes occurred.

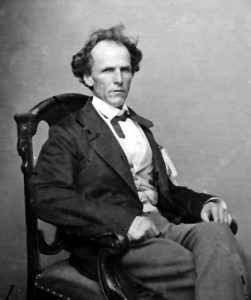

General James H. Lane

When Governor John Geary arrived in the territory, he issued a proclamation ordering all armed bodies to disperse. General James H. Lane was near Topeka at the time and did not know of the proclamation. With his party, he was starting for Holton when a messenger arrived from Ozawkie, with the news that the border ruffians had burned Grasshopper Falls and intended to burn the other Free-State towns in the vicinity to drive the settlers out of the country. The assistance of Lane and his command was asked for, and they marched to Ozawkie, where the local Free-State men increased their force. Having restored order there, Lane learned that an armed force of pro-slavery men was at Hickory Point and marched there determined to capture them.

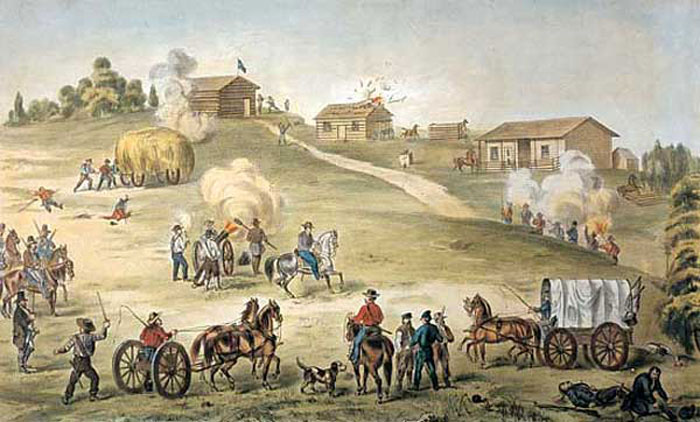

Upon arriving on September 13, Lane and his Jayhawkers found about 100 men assembled, under the command of Captain H. A. Lowe, the owner of Hickory Point, assisted by about 50 Carolinians, who had been committing outrages throughout the country. An attack was made, but the pro-slavery men were too well fortified to be driven out.

Understanding he lacked the artillery to attack the log buildings, Lane and his men retreated. Lane then sent word to Lawrence for Captain Bickerton to bring reinforcements and the captured cannon “Sacramento.”

During the retreat, the Missourians pursued Lane’s forces and attacked, but the Jayhawkers returned fire. After receiving word that Territorial Governor John Geary had ordered a ceasefire, Lane withdrew.

After the news reached Lawrence, Colonel James A. Harvey gathered a company of recruits, started at once, marched all night, stopping at Newell’s Mills just long enough for breakfast, and arrived at Hickory Point about 10 a.m. Sunday. In the meantime, Lane had heard of the governor’s proclamation and had started for Topeka, expecting to meet the forces from Lawrence on the road. But Colonel Harvey, having taken the direct route, missed Lane. When Harvey and his forces came up, the pro-slavery men tried to retreat but were soon surrounded and took refuge in the log houses. No messages were exchanged. The cannon was placed in position about 200 yards south of the blacksmith shop and commenced firing. It was supported by about 20 men armed with United States muskets. The Stubbs company was stationed about 200 yards to the southeast in a timbered ravine. The first cannon shot passed through the blacksmith shop and killed Charles G. Newhall.

Finding it impossible to dislodge the pro-slavery men, Colonel Harvey ordered a wagon load of hay backed up to the shop and set it on fire. Some of the men were fired upon but got away under cover of the smoke. Soon after, a white flag was sent out from the shop asking permission for some non-combatants to leave the buildings. Messages were sent back and forth, and a compromise was reached by which each party agreed to give up its plunder, and all non-residents of each party were to leave the country. One pro-slavery man was killed, and four were wounded. Three Free-State men were shot in the legs, one through the lungs and one had a bruised head. This ended the battle of Hickory Point.

Afterward, 100 Free-Staters were arrested by U.S. troops and taken to Lecompton where they were imprisoned and charged with murder. They were later acquitted due to acting in self-defense. In the meantime, the pro-slavery Missourians left the area.

In 1865, when the Butterfield Overland Despatch stagecoach left Atchison, Kansas, making its way to Denver, Colorado on the 592 miles long Smoky Hill Trail, Easton was a stagecoach stop. It remained a stagecoach stop until the Kansas Pacific Railroad was also pushing towards Denver, and by 1870, the stage line was no longer needed.

Afterward, Hickory Point faded into obscurity.

Today, the battle site is designated by a historical marker on U.S. Highway 59 about five miles north of Oskaloosa.

Just 1/4 mile from the Battle of Hickory Point marker, is the farm on which painter John Steuart Curry was born. The farmhouse has been moved to Oskaloosa. John Steuart Curry would become known for his painting of abolitionist John Brown at the Kansas State Capitol, and other artworks.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, June 2022.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War

Extinct Towns of Jefferson County

Jefferson County Photo Gallery

Territorial Kansas & the Struggle For Statehood

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Civil War on the Border

Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Kansas State Historical Society