University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas, by Alfred Lawrence, 1913.

Indian Mission Schools

Past Colleges & Universities of Kansas

The first territorial legislature convened in July 1855 and enacted the first body of laws governing Kansas. One section reads:

“That there shall be established a common school or schools, in each of the counties of this territory, which shall be open and free for every class of white citizens between the ages of five and 21 years, provided that persons over the age of 21 years may be admitted into such schools on such terms as the trustees of such district may direct.“

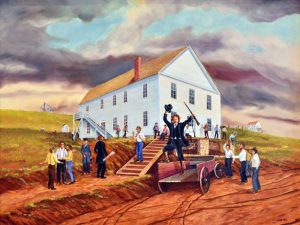

General James Lane at Constitution Hall in Lecompton, Kansas by Ellen Duncan, 1982.

Owing to the political situation, little was done to administer the laws enacted by this legislature or by the 1857 legislature. The first Free-State legislature, convened in 1858, passed additional laws to organize, supervise, and maintain common schools. James Noteware was appointed territorial school superintendent on the day this act was approved. He served until December 2, 1858, and was succeeded by Samuel W. Greer, who was in office until January 7, 1861. From that time until April 10, 1861, John C. Douglas was superintendent. Superintendent Greer submitted a report to the legislature on January 4, 1860, covering 16 counties and 222 school districts. Douglas County led the list with 36 organized school districts. There were 7,029 people of school age; $7,045.23 had been raised to build schoolhouses; the amount of money by private subscriptions was $6,883.50; and the amount of public money for schools was $6,283.50.

William R. Griffith was elected the first state Superintendent of Public Instruction, taking his office in February 1861. His report for that year showed that 500,000 acres of land granted under the act of Congress of 1841 had been selected by commissioners appointed by the governor; also, 46,080 acres were granted for the support of the state university. Twelve county superintendents reported to him, but not all counties had been organized into districts. William Griffith’s successor was Simeon M. Thorp. His 1862 report, based on 20 county superintendents’ reports, indicated that 304 school districts had been organized. The school taxes for that year were $19,289, and the number of school children was 14,976. Isaac T. Goodnow was elected superintendent in 1863 and served until 1867. Mr. Goodnow’s 1866 report indicated 54,000 schoolchildren, 871 school districts, and 1,086 schoolteachers. He urged uniformity in school books, a revision of school laws, the compelling of school districts to use the textbooks officially recommended, the employment of a deputy state superintendent, the making of the office of county superintendent a salaried office, a change in the law for issuing bonds for building school houses, and a report of the law limiting taxes in school districts. Peter McVicar was superintendent from 1867 to 1871. His report embraced recommendations concerning graded schools, the conduct of primary schools, the age of admission, and courses of study. During the 1870s and 1880s, public schools were enhanced by new laws, improved organization, and better conditions.

In 1903, the legislature passed an act requiring that all children between the ages of eight and 15 attend school for a specific portion of each year. The law provided for a truant officer whose duty was to enforce the provisions of this act. The truant officer was under the supervision of the county superintendent. All the elementary schools of Kansas used the same textbooks. The 1907 legislature created a school textbook commission consisting of “eight members to be appointed by the governor and with the consent of the Senate.” This commission was empowered and authorized to select and adopt a uniform series of school textbooks for public schools.

For many years, efforts were made to install libraries in the state’s schools. By 1910, approximately half of rural schools had libraries containing 274,793 volumes.

The First Schools in Kansas. The first schools in Kansas were mission schools for Native Americans. When Kansas was organized as a Territory and white settlers began to make their homes there, their children’s education became a top priority. In the summer of 1855, the first Territorial Legislature passed a law establishing common schools, thereby laying the foundation for our public school system.

Early Territorial Schools. In January of 1855, when the town of Lawrence was only six months old, a school was opened in the back of Dr. Charles Robinson’s office. A term of school was held in Lawrence every winter thereafter. Other towns also maintained schools, as did a few country communities. However, the settlers’ claims were widely dispersed, and the dangers during the days of raids and warfare were so great that country schools were almost an impossibility in the first few years.

Subscription Schools. Many of the earlier schools were “subscription schools,” meaning they were not public schools supported by a tax levy; teachers’ salaries were paid from tuition charged to each student.

Beginning of the School System. By 1859, when Territorial conditions had become more settled, the Legislature turned its attention to education. It enacted a set of school laws that have since served as the basis of our education system. While Kansas was still a Territory, a few districts were organized, schoolhouses were built, and the minimum school term was three months.

Schools After the Civil War. Little educational progress was made during the Civil War, but when peace had come to Kansas, and the people could turn their minds to the needs of their homes and communities, schoolhouses built of legs or sod sprang up everywhere, for the pioneers had brought with them a desire to educate their children. Sometimes, the settlers did not even wait to organize their district before gathering and beginning work on their schoolhouse. Where there was a timber supply, they made their buildings of logs. On the prairie, they built of sod. With the breaking plow, they sliced long pieces of sod, 2 to 4 inches thick and 12 to 14 inches wide, which were mortared with soft mud and used like brick to build the walls. The roof was sometimes made of lumber, but often the sod was laid over a framework of brush and poles. Whether the building was made of logs or sod, the floor was usually of dirt sprinkled and packed until it was hard and smooth. As the country grew in population and resources, these buildings were replaced by others made of lumber, brick, or stone, but the little log and sod schoolhouses served the pioneers well. They were used not only for school purposes but for religious services and social gatherings, spelling schools, singing schools, and literary societies. The schoolhouses were the social centers in early Kansas.

Although the minimum term was three months, it was typically extended slightly to benefit the younger children. As a rule, the older boys and girls attended school only during the winter, when they could be spared from the farms.

The school work in those days consisted chiefly of the three R’s, “readin’, ‘ritin’ and ‘rithmetic.” In most cases, the students started each year at the beginning of their books and worked as far as possible. This continued winter after winter until the girls and boys were 18 to 21 years old, or older. There was no such thing as graduating from the country schools; the students attended until they were ready to quit. Since there were almost no high schools in the State, few children received more than a typical school education, and most teachers had no more than that.

Changes in the District Schools. Conditions were quite different in the country schools. Many of them had terms of eight months, a few had nine months, while seven months was the shortest term permitted by the State. The truancy law required attendance during the whole term, whatever its length. In time, the sod and log schoolhouses of pioneer days were replaced by neat little box-like buildings usually constructed of wood, though occasionally brick or stone. These, in turn, were rapidly disappearing, and their places were being taken by buildings that were larger, more beautiful, more comfortable, and far better adapted to educational needs. Teachers’ qualifications have been raised. In earlier days, when there were but few high schools, many teachers had no education beyond what they had obtained in the country schools. By 1920, 90% of the state’s rural teachers were high school graduates, and this percentage steadily increased. The work of the rural schools has expanded far beyond the “three R’s.” In addition to regular work, it now includes as much time as permitted for subjects such as music, manual training, agriculture, and household arts. Rural schools have received considerable attention recently and are undergoing rapid improvement. Several hundred have already met the State’s requirements for a “standard” school, and a few have met the requirements for a “superior” school; these lists are continually expanding.

Consolidated Schools. Consolidation was generally considered a method of improving conditions in rural schools. A consolidated district was one formed by the union of several districts. A larger building replaced the little district schoolhouses, usually centrally located, to which the children were conveyed in wagons provided for that purpose. At a larger scale, the consolidated district can employ more teachers, maintain more equipment, and offer a greater variety of subjects. There were several consolidated schools in the State by 1920, and the plan was being considered in many communities. The Good Roads movement did much to encourage consolidation.

Growth of the High School. Several years had passed since Kansas had many high schools. Four schools were listed as accredited high schools of the State in 1876. By 1886, the number had grown to 36; by 1896, it had reached 77. From then on, the number increased rapidly until, in 1918, there were 630 accredited high schools in the State, 121 of which were rural. Until about 1905, the standard for an accredited high school was only three years. It has been four years since that time.

In the early years, the primary purpose of high school was to prepare students for college, and the curriculum consisted solely of subjects suited to that purpose. Later, the idea was that this was only one of the purposes of high school, the other being to supply the great mass of students who would never go to college with the best possible preparation for living. To accomplish this, curricula were broadened to include music, manual training, agriculture, commercial work, household arts, teacher training, and industrial training. Until recently, high schools were established only in towns and cities. They were soon found in consolidated districts, in rural districts, sometimes in small towns in those districts, and sometimes in entirely rural communities. By 1920, no county in the state had an accredited four-year high school.

Institutions of Higher Learning. The Kansas settlers’ deep interest in education matters was nowhere more apparent than in their early establishment of institutions of higher learning. In the first Constitution, made in 1855, one read, “The General Assembly may take measures for the establishment of a university,” and again, “Provisions may be made by law for the support of normal schools.” These matters were not lost sight of, and almost immediately after the admission of Kansas as a state, this ambition was found in establishing the Normal School, the Agricultural College, and the University.

Normal Schools. The State Normal School at Emporia opened in 1865 with 18 students enrolled. It used the upper floor of the new schoolhouse that had just been built for Emporia, which was then but a small town. There was no furniture, and the only equipment was a Bible and a dictionary. Seats were borrowed from a neighboring church. But the Normal soon had a building of its own. In later years, this was replaced three times by larger and better ones, and many new buildings were added.

The Normal School was based on the principle that it was necessary to know what and how to teach, and that there were discoveries and advances in teaching methods, as there were in other fields, such as medicine and agriculture. The purpose of the Normal School was to train teachers. When our State Normal School was established, there were not more than a dozen other such schools in the United States, and none that prepared teachers for high school positions. By 1920, there were many normal schools, but none were larger than ours or more amply equipped to prepare teachers for all lines of teaching. The course of study, ranging from kindergarten through completion of a college course, places our State Normal School in the front rank of institutions of its kind. In 1901, the Western Branch State Normal School was established at Hays, and in 1903, another branch, the Manual Training Normal School, was opened at Pittsburg. Each of these has since been made an independent school. The one at Hays became the Fort Hays Kansas Normal School.

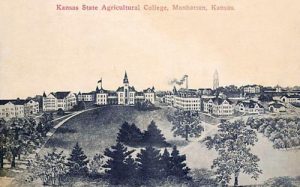

The Agricultural College. In 1862, Congress passed an act authorizing land grants to states to establish agricultural and mechanical arts colleges. Kansas was among the first states to accept the endowment. The following year, Bluemont Central College, a Methodist school in Manhattan, was transferred to the State and renamed the State Agricultural College. During the first ten years, the Agricultural College’s growth was very slow. This was chiefly because industrial education was new and received little attention. The College provided only limited instruction in agriculture or manual training; what it did provide was merely supplementary. It was doing little to educate the farm or the workshop. In 1873, the school was reorganized.

Farmers began to show interest in it and discuss its potential. Such subjects as Latin and Greek were dropped, and agriculture, home economics, and mechanical arts were emphasized. Workshops, print shops, kitchen and sewing rooms, agricultural implements, and livestock were provided. This was a highly advanced step at the time, and it elicited some opposition. It was called the “newfangled” education, and farmers who read and studied farming methods were often sneered at as “book farmers.” But in time, people began to view these things in a different light. It has now come to be generally recognized that successful farming requires a broader and more varied knowledge than almost any other business and that in an agricultural state like ours, nothing was more important than the training of its citizens for home and farm life. The Agricultural College soon assumed leadership in the state’s agricultural and industrial interests and became one of the largest agricultural colleges in the United States.

The University. The University of Kansas was established by an act of the Legislature of 1864, and its object, as stated in this act, was to “provide the inhabitants of the State with means of acquiring a thorough knowledge of the various branches of literature, science, and the arts.” The university idea was hundreds of years old, so there was nothing new in the thought of a university in Kansas.

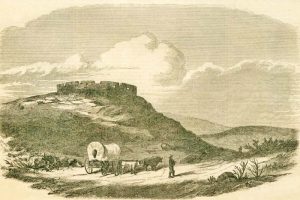

The University of Kansas was built on the flat-topped hill in Lawrence, where the first party of free-state settlers pitched their tents. It opened in 1866 with 40 students and three professors. By 1920, there were 20 significant buildings on Mount Oread. The university’s central department was the college, which provided a liberal education in languages, sciences, mathematics, history, and other subjects. In addition to the college, there were schools of engineering, fine arts, law, pharmacy, medicine, and education. Ours now ranks high among the universities in the United States.

Control of State Schools. Altogether, the University, the Agricultural College, and the Normal Schools employed about 700 instructors and enrolled between 8,000 and 9,000 students each year by the early 20th century. The total annual cost to the people of Kansas at that time was nearly $2,000,000. These schools, together with the School for the Blind in Kansas City and the School for the Deaf in Olathe, were, in 1913, placed under the management of a three-member board called the Board of Administration. In 1917, the Board of Administration was reorganized, and the State’s penal and charitable institutions were placed under its control.

Denominational Colleges. In addition to the State institutions, Kansas had more than 30 denominational colleges by 1920. A few of the largest were Baker University at Baldwin, Washburn College at Topeka, Ottawa University at Ottawa, Friends University at Wichita, Southwestern University at Winfield, and the College of Emporia. There were also several business colleges and a few independent schools.

Other Provisions for Education. In addition to the schools where people in Kansas may obtain an education, every effort was made to provide other educational opportunities through extension work, public and traveling libraries, and night schools. The State Normal School, the Agricultural College, and the University all conduct extension work, meaning they offer correspondence courses, send lecturers, and, in various other ways, extend their work to those who cannot attend the schools. Many communities maintain free public libraries, and the State maintains a traveling library. Night schools were provided in several of our larger cities. Education was now possible for anyone who wanted it. All of this has been brought about within little more than a half-century, and the people of Kansas have every reason to be proud of what they have accomplished in the interests of education.

Summary. Education in Kansas began with mission schools and was among the earliest priorities during the territorial period. There were many subscription schools before district schools were organized. The organization of districts began in the Territorial period and kept pace with settlement. The University, the Normal School, and the Agricultural College were established during the Civil War. Afterward, many denominational colleges were established, high schools were developed, and other educational means were provided. Significant educational progress has been made.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated January 2026.

Also See:

Sources:

Arnold, Anna E.; The State of Kansas; Imri Zumwalt, state printer, Topeka, Kansas, 1919.

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.