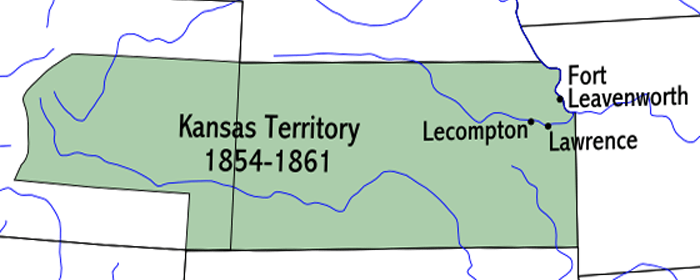

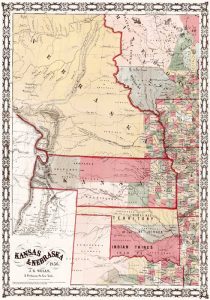

Little Known of Kansas in 1854. Kansas in 1854 was, to most people, only a name, a part of the great desert in the Far West, an Indian country. Many of those who had crossed it in emigrating to California had been impressed with the beauty and richness of the country and had written back glowing accounts of it. Some of them had returned from the coast and were now numbered among our early settlers. When its organization as a territory brought it into such prominence, knowledge of Kansas soon became more general.

Advantages of the South. The people of the South felt confident that they could make it a slave state, for they had gained many victories in Congress, and President Franklin Pierce, was in sympathy with them. Moreover, they were closer to Kansas than the northern people, and the only state touching Kansas was the slave state Missouri.

Advantages of the North. The people of the North, however, possessed one significant advantage. The population of the South consisted primarily of plantation owners and their slaves, and it was not easy for these men to leave their property or take it into a new and untried country. On the other hand, the North was a land of small farms and shops and many laborers. Moreover, there was much foreign immigration into the United States in those years. Since the employment of slaves left no place in the South for white laborers, most immigrants entered the northern states and added to the number of those who were ready and anxious to go farther west. Consequently, many more settlers came into Kansas from the North than from the South, but the Southerners tried to overcome this handicap in other ways.

The Coming of the Missourians. The South planned to use Missouri as the stepping stone to Kansas. Immediately following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, many Missourians came over to Kansas and took as claims large tracts of the best lands, in some cases not even waiting for the removal of the Indians. Settlers who asked for claims were required to build houses and use the land for homes for a long time. While some of the Missourians met these requirements, many of them did not come here to live. They notched trees, posted notices, or laid rails on the ground in the shape of a house, or in some other way indicated their claims, and returned to their homes in Missouri, coming back only to vote or to fight when it seemed to them necessary. While in Kansas, however, they held a meeting at which it was resolved that: “We recognize slavery as always existing in this Territory” and “We will afford protection to no abolitionists as settlers of Kansas Territory.”

Handicap to Northern Emigration. The free-state people could not step over a boundary line and be in Kansas. They lived a long way off, the trip out here was expensive, and little was known of the new Territory. It was a land without homes or towns, churches, schools, or newspapers, and the Northerners knew that people would hesitate to start to Kansas under all these difficulties.

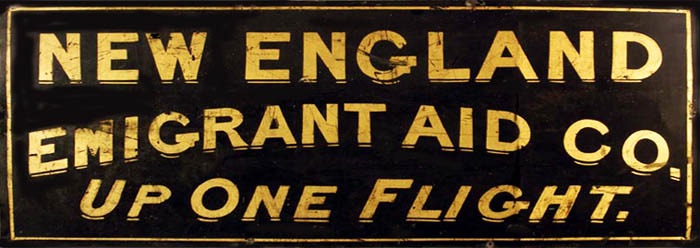

The New England Emigrant Aid Company. So it came about that even while the Kansas-Nebraska Bill was pending in Congress, a Massachusetts man named Eli Thayer had thought out a plan for assisting and encouraging the people to undertake the long journey. He planned to form a company to induce and organize emigration to Kansas and reduce the expense and hardship involved. This was not to be done as charity but to be done on a business basis. Thayer aroused public interest in his plan by constant writing and speaking. Since the people were ready to listen to whatever promised to aid in making Kansas a free state, enough money was soon raised to organize a company called the New England Emigrant Aid Company. It gathered and published information concerning the new country and organized emigrants into large parties to make the journey more pleasant, reduce expenses, and lessen the danger. Competent guides were sent with the parties. The company established schools, newspapers, mills, hotels, and other improvements that tended to lessen the pioneers’ hardships and further the new Territory’s development. Several similar organizations were formed, but none were as well known nor efficient as the New England Emigrant Aid Company.

Work of the Emigrant Aid Companies. Hundreds of people came here under the management of these companies, but probably the greatest service the companies performed was giving an immense amount of publicity and advertising to Kansas. Newspapers were filled with descriptions of the new Territory’s loveliness, fertility, and future greatness. People were urged to go to Kansas at once to secure the country’s advantages and help in saving it from slavery.

Emigrant Aid Society

In this way, interest and enthusiasm were aroused over the whole North. Still, for everyone who came in one of the emigrant aid parties, many came independently, especially from the states farther west than New England — Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa.

Southern Organizations. The organizations in the North aroused many bitter feelings in the South, and a reward was offered for the capture of Eli Thayer. The South soon formed organizations, some known as Blue Lodges, Social Bands, and Sons of the South.

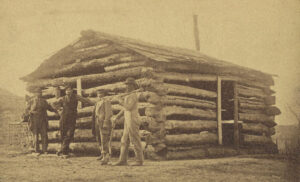

Early settlers’ cabin in Saline County, Kansas, about 1875.

The Coming of the Free-state Settlers. As has been stated, the Missourians came to Kansas immediately after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act on May 30. Still, the free-state people were not far behind, for on August 1, just two months later, the first party of emigrants sent out by the New England Emigrant Aid Company reached the Territory. Even these were not the first Free-State men to arrive; a few who had come independently were already here.

The First Party of Settlers. This first party consisted of only 29 men. It was difficult to organize, for coming to Kansas was considered dangerous. Hundreds of people gathered to bid these men farewell as they started on their long journey to participate in the great conflict between freedom and slavery. Many would not have been surprised had the whole party been murdered on their arrival in Kansas, but when nothing of the kind happened, others took courage, and more parties soon followed.

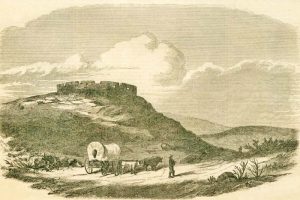

They Reach the Present Site of Lawrence. The pioneer party reached St. Louis, Missouri, by railroad, boarding a steamboat, and came up the Missouri River to Kansas City, then a town of only 300-400 people. There they purchased an ox team to transport their baggage and set out on foot into Kansas on Saturday evening. By Tuesday noon, they reached the present site of Lawrence, where they pitched their tents on a big flat-topped hill. Today the significant buildings of the University of Kansas stand on this hill, which is still called Mount Oread, the name given to it by this first party of pioneers. The weather was sweltering; a drought had parched the earth, and prairie fires had destroyed the grass, but the pioneers were not discouraged. They staked out claims in the surrounding country and began preparations for the future. The Second Party Arrives. In a short time, the second party arrived. It was under the direction of Dr. Charles Robinson and Samuel C. Pomeroy, leaders in the free-state cause during the whole Territorial struggle.

This party was much larger, and some members were women and children. The town was now laid out, organized, and named Lawrence. On the arrival of this party, a boarding house was established by two of the women. It was thus described by a writer of that time: “In the open air, on some logs of wood, two rough boards were laid across for a table, and on washtubs, kegs, and blocks, the boarders were seated around it.” A short time later, a hotel was opened. It was constructed by driving two long rows of poles into the ground, which were brought together at the top and sides thatched with prairie grass. The ends were made of cotton cloth, and the building resembled the “stray roof of a huge warehouse.”

Getting Ready for the First Winter. The people lived in tents and houses of thatch through the summer and fall, but in the meantime, all were busy getting log cabins ready for the winter. By winter, several things had been accomplished: a sawmill was running, churches had been organized, two newspapers had been established, and Lawrence had been granted a post office with mail from Kansas City three times a week. The population was about 400. Many of the cabins still had cloth doors and were without floors, and the people had all they could do to care for themselves through the winter. When two more parties of emigrants arrived at the beginning of winter, the task became much more difficult.

The Actual Settlers’ Association. Besides building homes and developing the town, there was much to occupy the minds of the pioneers. Missourians had taken claims over much of the eastern part of the Territory. While some pro-slavery settlers had come to make homes, just as the free-state settlers had, most of those who had taken claims were living in Missouri. When the first party came to Lawrence, the members bought out the claims where they located their town; later, other claimants appeared, and there was much trouble over the title to the land. The same trouble arose regarding the land many free-state settlers took outside Lawrence. It became common for a Missourian to come over and lay claim to some free-state man’s land and warn him to leave the Territory. This caused the formation of the Actual Settlers’ Association, which helped to adjust to such difficulties.

Other Towns. Lawrence was not the only place in the Territory that was settled before the close of the first winter. People came in from the north, east, and south, settling on claims and starting other towns. The principal pro-slavery towns were Leavenworth, Atchison, and Lecompton. Free-State towns were Lawrence, Topeka, Osawatomie, and Manhattan. Leavenworth and Atchison were founded by people from Missouri and became outfitting points for travelers over the California and Mormon Trails since they were on the Missouri River. Lecompton, on the Kansas River, not far from Lawrence, soon became the headquarters of the pro-slavery people and, for several years, was the Territorial capital. Topeka was founded with the hope of its becoming the capital of Kansas. Osawatomie soon became an important free-state center. Manhattan, on the Kansas River at the mouth of the Big Blue River, was called Boston for the first few months. On the arrival of a party of 75 people from Cincinnati, Ohio, the name was changed to Manhattan. This party made the entire trip from Cincinnati to Manhattan by boat.

Summary. When Kansas Territory was organized, little was known, but because the North and the South wanted it, knowledge of Kansas spread rapidly. The South had the support of every branch of the National Government, and the added advantage was that the only State touching Kansas was pro-slavery. The advantage of the North lay in the fact that it had a much larger number of people who were free to move to a new country. The pro-slavery Missourians came in at once and took claims. A few free-state people came within a month, and in two months, the emigrant aid parties began to arrive. The fact that many Missourians had staked out claims and gone back home led to numerous claim disputes and caused the organization of the Actual Settlers* Association. By winter, four emigrant aid parties had arrived at Lawrence, many settlers were living on their claims, and each side had started several towns.

Bleeding Kansas Fight.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023. Source: Arnold, Anna E.; The State of Kansas; Imri Zumwalt, state printer, Topeka, Kansas, 1919.

Also See:

African-Americans – From Slavery to Equality