Frontenac, Kansas, was founded as a coal mining town in 1886 in the Cherokee-Crawford Coal Fields. Today, it is the second-largest city in Crawford County.

It began when the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad leased the land and formed the Cherokee and Pittsburg Coal and Mining Company. The Cherokee-Pittsburg Coal Company founded the town when they sank the Santa Fe Mine No. 1.

The police department was organized in 1886, consisting of two marshals.

In 1887, the name was changed to Frontenac, and A. A. Robinson, an official of the Cherokee-Pittsburg Coal Company, laid out the town. Though it is unknown where the town’s name came from, it is thought it might have been named after Fort Frontenac in Canada, a source of early recruitment for the coal mines.

The Santa Fe Railroad advertised in many countries, and soon, flocks of immigrants came to work and settle in the area. Frontenac quickly became a diverse city, rich with culture.

A post office was established on June 23, 1887. Dr. J. S. Patton opened the first business, which served as a grocery store, dry goods store, and undertaking business. Serving as both a doctor and undertaker, Patton’s motto was “Everything from the Cradle to the Grave.”

The first Catholic Mass was held in 1887 in the home of Andrew Walker.

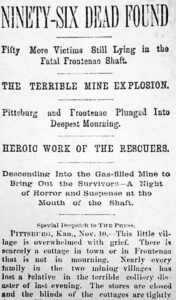

On the night of November 9, 1888, Frontenac had the worst mining disaster in Kansas history when a coal dust explosion killed 44 men and boys.

A terrible explosion occurred in the Cherokee and Pittsburg Coal and Mining Company Mine No. 2, also known as Mount Carmel No. 2. The blast was so strong that it broke windows in nearby houses. Though Mine No. 2 was considered one of the best, most modern mines in the state, it was also dry and had problems with coal dust accumulations.

“Yesterday evening witnessed the most terrible holocaust that ever occurred in this mining district or the West. Mine No. 2 of the Pittsburg and Cherokee Mining Company at Frontenac blew up, causing a horrible toll of life. The number of lives lost is not known. Men in the mine at the time of the explosion numbered 164. Many of them made their way out alive and uninjured. At least 200 men, women, and children are gathered around the shaft of the mine. The cries of those whose husbands or fathers are known to be below are heartrending. Entrance to the mine is being achieved as fast as is humanly possible, but the main entrance is absolutely blocked, and imminent danger attends every attempt by the air shaft… Men are driven to desperation by pitiful appeals by weeping women and girls to get their husbands, fathers, and boys out before they all die. Snow and rain have been falling continuously since the explosion yesterday evening at 5 o’clock. Half-clad women shiver and huddle about the top of the shaft, pleading for someone to give them tidings of their loved ones. Every available doctor from Pittsburg, Girard, Litchfield, and other places over the district is at the shaft and ready to give emergency treatment.

More than 100 men are believed to be lying dead in the mine. Those who escaped report horrifying tales of the explosion and after fire which blasted its way through the workings. The violence of the shock rocked Pittsburg and all surrounding territory. Half an hour after the explosion, a ragged, bleeding man staggered into Pittsburg. He said that all the men in the mine except himself and one other had been killed. Horses quickly were harnessed to wagons, and soon the villagers were hurrying through a fierce snow and sleet storm to the scene of the disaster. Rescue parties have endeavored to enter the mine but have been driven back by foul air. The explosions demolished the air fans, and men are working frantically to replace them so air can be sent into the mine.”

— Pittsburg Headlight, November 10, 1888.

The dead included immigrants from France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, England, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, and Austria. The oldest victim was 45, and six teenagers were killed, including two 13-year-olds. Every doctor from Pittsburg and many from Girard, Litchfield, and the surrounding area responded.

A memorial to those who sacrificed their lives stands on 2nd Street in Pittsburg.

The first Methodist service was held in 1890 in the Santa Fe Depot. In 1894, the Catholics built a small wooden church, with Father Podgorsek as the first resident pastor.

In 1895, as more and more miners settled in the area, Frontenac became incorporated as a third-class city.

The first city hall, located in the 100 block of Crawford Street, was built and dedicated in 1896.

During the last decade of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, the town was populated primarily by immigrant families from eastern and southeastern Europe. They were predominantly Sicilian, Italian, and Slavic people from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Its maximum population neared 4,000 and housed several drinking parlors despite the state’s increasingly strict ban on the distribution, sale, and manufacture of alcoholic beverages.

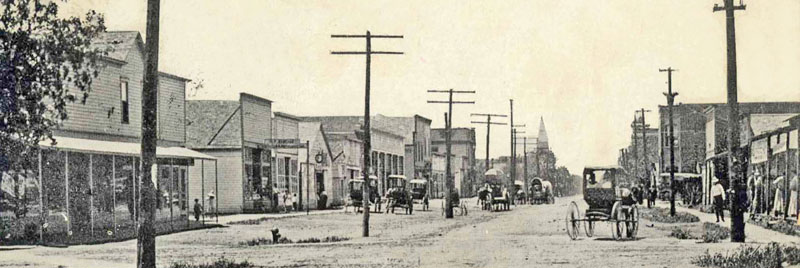

By the early 1900s, Frontenac was a flourishing town of 2,000 inhabitants. At that time, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad furnished transportation, and the Joplin & Pittsburg electric trolley cars carried people to and from Pittsburg. The city maintained excellent schools, and churches were well patronized. Several stores, a post office, hotels, and boarding houses were also well represented. The coal shafts were 120 feet deep, where 40 inches of excellent coal was mined.

Frontenac, Kansas Street, early 1900s.

In 1904, electric lights were first installed, and telegraph and telephone companies were established the following year.

In 1906, the first macaroni factory in Kansas was established in Frontenac by the Griglione family.

On February 9, 1907, it became a second-class city. Most new residents were from France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Belgium, and Ireland. That year, a 75,000-gallon water tank and reservoir were established, which held 350,000 gallons. The water was supplied from two wells.

By 1910, Frontenac had a bank, an international money order post office, an express and telegraph service, telephone connections, several good mercantile establishments, and hotels. In addition to its good public school system, a Catholic academy was in Frontenac. At that time, the population was 3,396, a significant gain from the previous decade.

In 1916, Peter Menghini and his brother, Antone, founded the Menghini Coal Company, with Peter taking charge of operations. Peter, an Italian who had come to Pittsburg at the age of 16, owned and operated the company that once owned the largest digging shovel.

Realizing the financial opportunities available in the mining community, Peter’s miners were paid from the Menghini home; from there, they could go next door to the family-owned butcher shop to buy fresh meat and on to the Menghini Mercantile Store to get the other supplies their families needed. These financial opportunities led the brothers to other business ventures in the area, such as the Miners State Bank. The company strip-mined until 1945, with their last dig being a 30-feet deep, 20-acre strip pit east of Frontenac.

Miners State Bank was one of the first banks in Frontenac. It first received its charter on January 29, 1919, and opened for business in June. When the bank first began operations, another bank was doing business in the city.

Coal mining remained the town’s occupational base until World War II, when its economy began to change.

Frontenac’s post office closed on November 29, 1957, when the mail delivery was switched to Pittsburg.

As of the 2020 census, Frontenac’s population was 3,382. The town is located three miles northeast of Pittsburg.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, April 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Frontenac Schools

Historical Marker Database

Home Authors; A Twentieth Century History and Biographical Record of Crawford County, KS, Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, 1905

Pittsburg Memories

Wikipedia