Old Lost Spring, Kansas in Marion County was a watering-place on the Santa Fe Trail.

Sources of water were crucial to travelers along the Santa Fe Trail because they could not carry adequate supplies of water. Lost Spring was an overnight camping spot that provided water for travelers and their livestock. It was conveniently located a day’s travel west of Diamond Spring and a day’s travel east of Cottonwood Creek. Some say the spring got its name because it dried up in some years, thus becoming “lost.”

Long before it was known to travelers on the Santa Fe trail, Lost Spring was used by the Indians, early explorers, and traders. The Kanza Indians are said to have called it “Nee-nee-oke-pi-yah,” and the Spaniards named it “Aqua Perdida.” Both phrases mean “lost water.”

“Came to a place, called ‘Lost Spring,’ a most singular curiosity. The stream rises suddenly out of the ground, and after rushing over the sand a few yards, as suddenly sinks, and is no more seen.” — William Richardson, Doniphan Expedition, September 1, 1846

In 1859, Lost Spring Station was established by George Smith, who had previously operated a stage station at Cottonwood Crossing. It first served as a “road ranch” with a hotel and tavern. It was located on the south side of the trail southeast of the spring and situated on a knoll where one could see up and down the treeless ravine and creek bed. The three-room structure measured 30 feet by 40 feet with an L extension on the south side containing the dining room and kitchen. The construction was of siding with the roof covered with sod and dirt. Southwest of the ranch house was a stockade with eight-foot posts enclosing about an acre of ground.

Smith did not own the station long, as he soon lost the station to Jack H. Costello in a poker game. When Costello was just a teenager, he enlisted as a drummer in the U.S. Army. He had served in the Mexican-American War, and at posts in New Orleans, Louisiana, and San Antonio, Texas. Like many other soldiers of his time, he had a reputation as being wild. He had just mustered out at Fort Union, New Mexico, and was returning east over the Trail with several others when they stopped at the Lost Spring Station for the night. George Smith and the travelers spent the night drinking whiskey and playing cards. Smith ran out of cash and gambled the ownership of the station. The next morning, Costello was in such a stupor he didn’t realize that he had won the station from Smith until Smith and the others saddled their horses and rode away.

Jack Costello completed the building of the station and stockade. He ordered more supplies and liquor and tended to cater to gamblers and toughs who came along the Trail. Costello was joined in the fall of 1859 by Thomas Wise and his family who had been unsuccessful gold seekers in Colorado. Wise had intended to just stay overnight but instead decided to stay because the land around there seemed excellent for farming. Costello and Wise became partners in the Lost Spring Station.

In case the spring got “lost,” a well was dug south of the house in 1860.

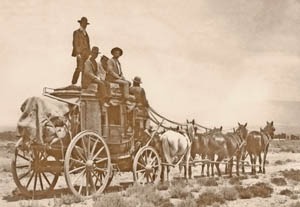

It is unknown when Costello’s hotel and tavern became a mail stage station. It is possible that Costello’s Lost Spring establishment became a mail station prior to becoming a post office on August 29, 1861. At that time the mail stages ran weekly along the Santa Fe Trail. These included Jersey wagons or eight-passenger enclosed wagons because they carried mail and passengers. At the station, the various contractors who transported the U.S. Mail obtained supplies and fresh animals to pull the mail wagons or stagecoaches. The station also provided lodging and supplies for people traveling along the Santa Fe Trail. Two hundred or more prairie schooners, wagons, would camp in a circle some nights.

With the mail stages running weekly, more people came to Kansas Territory, and the road ranches and mail stations offered a place for people to congregate and drink liquor. This sometimes caused problems. In Tom C. Cranmer’s “Rules and Regulations by Which to Conduct Wagon Trains,” published in 1866, he said that Wagonmasters are “never to idle your time about a station, town, or grocery” and to “never allow card playing…” in addition to the general prohibition of liquor on wagon trains.

The Station was said to have catered to the lawless element, gamblers, and toughs, with gambling and consumption of liquor. Consumption of liquor is confirmed by the recording of a liquor license. Drinking and gambling supposedly led to a number of shoot-outs, resulting in several deaths at the Station. According to various references, one man was murdered in his sleep, and the body was thrown down the well. Five others died or were murdered, and were buried northeast of the station. There were supposedly seven more graves of those who died by unspecified circumstances, one of which was an Indian woman.

Though traffic continued on the trail for several more years, the post office at Lost Spring closed on May 23, 1864.

Santa Fe Trail traffic declined dramatically in Marion County in 1866, when the Kansas Pacific Railway reached Junction City, about 40 miles north and east of Lost Spring. Beginning on July 2, 1866, the mail stages left the railhead at Junction City traveling westward then southward and did not join the Santa Fe Trail until a point on the Arkansas River near the mouth of Walnut Creek. All stage stations and post offices east of that point were then no longer served by the “Santa Fe Mail.”

In 1865, a party of Indians kept the station under siege for a number of days, burning the hay and destroying the grain. Costello spent most of the time on the roof of the station and was not injured. In another incident, Wise was trapped on the roof for half a day by Indians begging for whiskey. The Indians left when travelers approached.

Wise and Costello operated the Lost Spring station and hotel until 1868 when Costello sold his interest in the land and the station to Thomas Wise. Costello then moved to Marion where he operated a general store and tavern and was elected Marion’s first Mayor.

A battle with Indians took place near the Station, in the late 1860s. The trail continued to be used for local travel and commerce and some minor military traffic. It was probably most often used by various travelers and emigrants who could not afford rail travel.

This spring is located about 250-300 feet north of 340th Road in a small grassy tract of land about 1.5 miles west of the town of Lost Springs. Scattered scrub trees now dot the immediate area where the spring is located. However, no trees would have been found there in the early days of the Santa Fe Trail travel. Several decades ago, the site was a popular picnic ground.

A branch of the Santa Fe Trail passed to the south of the spring and south of 340th Road, but no visible evidence of that trail remains in the immediate vicinity. This is where the stage station stood.

Today, the site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its association with transportation and commerce along the Santa Fe Trail.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, April 2022.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Marion County

Santa Fe Trail in Marion County

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

Sources:

Lost Spring Interpretive Panel

Lost Spring Historic Marker

Natitonal Register Nomination

Schmidt, L. Stephen, Santa Fe Trail Association, 2005