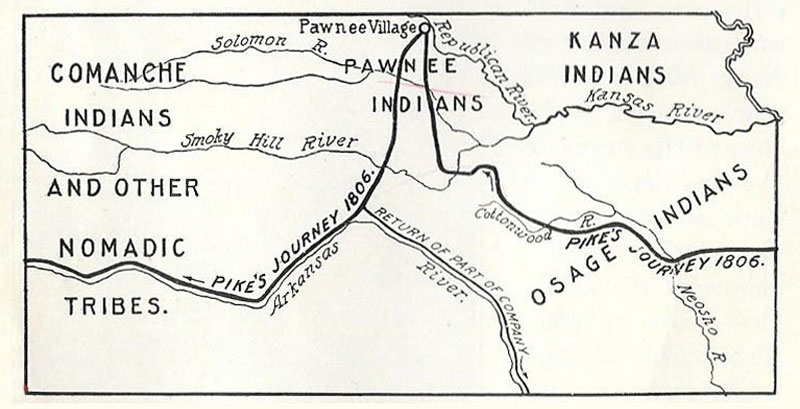

Kansas Indian Tribes, 1806.

The Pawnee Trail led from Pawnee Indian villages in central Nebraska, crossed the Saline River at Wilson Lake, and continued to the Great Bend of the Arkansas River in Kansas. The path followed the divides between stream systems to obtain the easiest travel route.

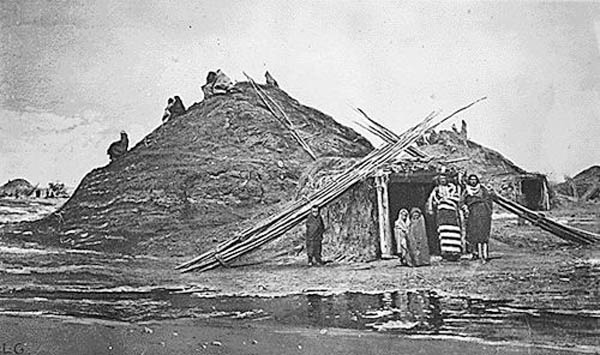

For years, the Pawnee regularly traveled from their home on the Platte River into Kansas, entering the state near the northeast corner of Jewell County, then south across Mitchell and Lincoln Counties across the northwest corner of Ellsworth County, to the Arkansas River in Barton County. From there, they would travel to various camps while hunting.

At that time, vast herds of bison and pronghorn antelope roamed the mixed-grass prairie. The Cheyenne tribe also utilized these grounds.

The Pawnee’s first probable contact with Europeans occurred in August 1541 at a Wichita Indian village just south of the Arkansas River, near where the Santa Fe Trail would run less than 300 years later. The Pawnee delegation met Francisco Vazquez de Coronado, the leader of a small Spanish exploratory force of fortune seekers. Although Spanish accounts indicate that this encounter played out on relatively amicable terms, the outcome may have been different if the Spaniards had detected any signs of precious metals. What Coronado accomplished for Spain was establishing a doctrine of discovery claim to the region.

Other early contacts between Native Americans and European Americans around the Wilson Lake area of Kansas were contacts with fur trappers and explorers. Some men traversing this area sought routes to Spanish/Mexican territories near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Many sites at Wilson Lake may be affiliated with the trail.

Explorers that traveled the trail included Pedro de Villasur in 1720, Etienne Veniard de Bourgmont in 1724, the Mallet Brothers in 1739, Zebulon Pike in 1806, David Meriwether in 1820, Charles Augustus Murray in 1835, and John C. Freemont from 1842 to 1853.

In 1720, the New Mexico governor sent a military expedition commanded by Lieutenant-General Pedro de Villasur to counter what was seen as French encroachments into Spanish territory. Possibly in the heart of Pawnee country near where the Loup River flows into the Platte River on about August 14, a combined force of Pawnee and Otoe warriors, perhaps joined by a few Frenchmen, struck a preemptive blow against colonialism, killing the Spanish commander, 34 soldiers, and eleven Pueblo scouts. The Pawnee ended Spanish plans to control the central plains through militant means. After that, Spain’s interest shifted to establishing trading relations with the Indians in the region. To the east, a more dangerous threat was looming. In 1803, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, without consulting any Indians within the vast affected area, purchased Louisiana territory from France, opening the door for westward Euroamerican expansion.

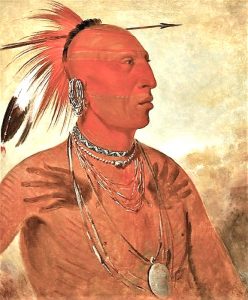

In 1806, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike crossed the Saline River twice as he searched for the headwaters of the Arkansas River. In September 1806, at the Pawnee town on the Republican River, just north of the Kansas-Nebraska border, a chief named Saritarish greeted Zebulon Pike and a small party of U.S. soldiers. In his report, Pike indicated that he had informed the Pawnee leadership that they were now living under the authority of the United States. Of course, the Pawnee lacked a reason to accept such an incredible declaration.

In 1816, 300 Pawnee laid siege to a party of hunters and trappers with Auguste P. Chouteau and Jules DeMun. Taking up defensive positions on an Arkansas River island, Chouteau’s men reportedly killed and wounded 30 attackers while suffering only four casualties, including one fatality. Located in western Kansas near Hartland, this site, known after that as Chouteau’s Island, became a landmark on the Santa Fe Trail. For years to come, travelers, in their dairies, journals, and letters, recalled the violent connection of Pawnee to the island.

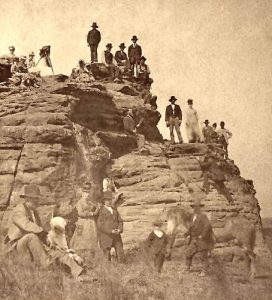

Other landmarks along the route with Pawnee names, including Pawnee Rock, Pawnee Fork, and the old Pawnee forts, also connoted warfare.

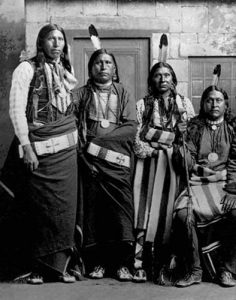

With a population that probably exceeded 30,000 people during the early 1800s, the Pawnee were the largest and most powerful group on the central plains.

With Euroamerican encroachments sparking conflict throughout the plains, U.S. officials sought to control Indians throughout the region through treaties, trade, and military means. In 1818, leaders of the Confederate Pawnee nations entered into separate peace and friendship treaties with U.S. representatives in St. Louis, Missouri. This would be the first in a long series of treaties to culminate in land cessions and placement of the Pawnee on reservations.

The independent-minded Pawnee leaders, although they referred to the U.S. president as their “Great Father,” were not only unwilling to subjugate their people under the unbridled authority of the United States, but they were also becoming increasingly intolerant to acts of Euroamerican trespassing.

The Pawnee Trail was an important early route to the southwest. Ultimately, however, the Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico, one of the most important commerce routes, was well south of the Pawnee Trail.

In 1821, the year of Willliam Becknell’s first trip to Santa Fe, the Pawnee lived free of foreign domination. Their existence on the plains stemmed deep into the past, probably much deeper than other Indians who had close contact with the trail.

Almost from the trail’s onset, popular perceptions among Euroamericans and Mexicans alike held that Pawnee were a formidable, unpredictable, and dangerous threat. Conversely, the Pawnee almost certainly held an almost identical view of them. Over the 20 or so years that followed, interlopers on the trail attributed many incidents involving tension, conflict, and violence to Pawnee and Comanche, whether the true identity of the involved Indians was known.

“The Indians believe the buffalo to be theirs by inheritance, not as game, but in the light of ownership, given them by Providence for their support and comfort, and that, when an immigrant shoots a buffalo, the Indian looks upon it exactly as the destruction by a stranger of so much private property.”

— Jim Beckwourth, Explorer & Mountain Man

In the fall of 1832, the Pawnee expressed their distress to U.S. agent John Dougherty about the destructiveness of trespassers. Relaying their concerns to William Clark, the superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis, he wrote: They state, however, that they have one cause of complaint against their white brothers, and that was the frequent passing and repassing in various directions of large parties of trappers and Santa Fe traders over their buffalo hunting grounds in consequence of which they are often obliged to go many days at a time without a mouthful to eat. They requested me to make known these facts to you that they might reach the ears of their great Father, who they confidently hoped would have pity on his Pawnee Children and either prevent these parties from traveling through their Country, destroying their beaver and running off their buffalo or give them something annually as an equivalent for the loss they thus sustain.

Clark promptly forwarded this information to the U.S. Secretary of War. In 1833, a U.S. treaty delegation visited Pawnee towns to acquire millions of acres of land southward from the Platte River. The treaty’s roots stemmed from the U.S. policy of territorial expansion.

Failing to come to a resolution, the Pawnee and other Plains tribes fought back against the encroachment upon their lands. They began to attack wagon trains, trail travelers, and other trespassers on the trail to slow the traffic. For years, they raided caravans, taking livestock, goods, and supplies, often leaving casualties behind. The U.S. Government intensified its efforts to protect trade and travel by establishing several forts along the trail to combat this.

Before long, the development of the Santa Fe trade and other forms of U.S. expansionism slowly propelled the Pawnee towards a state of dependency and political subservience under foreign dominion.