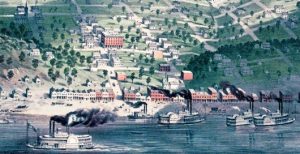

Lithograph of what Sumner, Kansas, might have looked like by Albert Conant.

Sumner, Kansas, was once one of the most important towns in Atchison County. Though long gone today, this old town has a fascinating history, complete with a ghost story.

“Three miles south of Atchison, Kansas, is the site of a dead city, whose streets once were filled with the clamor of busy traffic and echoed to the tread of thousands of oxen and mules that in the pioneer days of the Great West transported the products of the East across the Great American Desert to the Rocky mountains. It was a city in which, for a few years, twenty-five hundred men and women and children lived and labored and loved, in which many lofty aspirations were born, and in which several young men began careers that became historical.”

— H. Clay Park, former editor and part-owner of the Atchison Patriot

Located along the Missouri River about three miles south of Atchison, Sumner was founded by John P. Wheeler, a 21-year-old surveyor and attorney. John was described as “a red-headed, blue-eyed, consumptive, slim, freckled enthusiast from Massachusetts.” A Free-State supporter, Wheeler saw great opportunities in establishing a town on the waterway where abolitionists would be welcome. This was unusual, as pro-slavery advocates overwhelmingly populated the county.

In 1856, the site, situated on the high bluffs overlooking the Missouri River, was surveyed and platted. The new town was named “Sumner” in honor of George Sumner, one of the original stockholders of the town company, not for his older brother, Senator Charles Sumner.

To bring Sumner before the public, Mr. Wheeler engaged an artist to make a drawing of it. This was later taken to Cincinnati, Ohio, and a colored lithograph was made from it, which was widely circulated. However, the drawing was not actually the case but rather a dream (see drawing at top).

“Sumner’s first citizens came mostly from Massachusetts and were imbued with the spirit of creed and cant, self-reliance and fanaticism that could have been born only on Plymouth Rock. They had come to the frontier to make Kansas a Free State and to build a city, within whose walls all previous conditions of slavery should be disregarded and where all men born should be regarded as usual. The time — 1856 — was auspicious. Kansas was both a great political and military battlefield. Upon which the question of the institution of slavery was to be settled for all time.”

— H. Clay Park, former editor and part-owner of the Atchison Patriot

The fledgling city gained a post office in July 1857. John Wheeler became a member of the Kansas Territorial Legislature and pushed through a bill that would name Sumner as the Atchison County seat; however, the pro-slavery advocates defeated it, and the title went to Atchison. In the fall of 1857, the Sumner Town Company began the erection of a large brick hotel at the cost of $16,000. The bricks used in the construction were made on the ground, and the lumber used in the construction work came from a steamboat from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The hotel was completed in the summer of 1858.

In the fall of 1857, brothers John P. and D.D. Cone Brothers brought a printing outfit to Kansas. They were induced to locate in Sumner, where they began the publication of the Sumner Gazette, the first issue of which appeared on September 12. By October, the newspaper listed several businesses including Kahn & Fassler’s general store, the Sumner Brick Yard, Butcher & Brothers general store, John Armor’s steam sawmill, J.P. Wheeler and A.M. Claflin’s Lumber, Baker’s Hotel near the steamboat landing, S. J. Bennett’s boot and shoe store, and A. Barber’s general merchandise store. Other services were also offered, including Mayer & Rohrmann, carpenters and builders; William M. Reed, contractor; Allen Green, painter and glazier; Lietzenburger & Co., blacksmiths and wagon makers; and a physician, D. Newcomb.

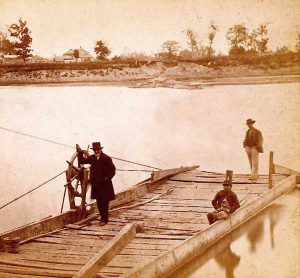

A ferry at Sumner was incorporated by the Territorial Legislature of 1858, with J. W. Morris, Cyrus F. Currier, and Samuel Harsh as the incorporators. This boat plied between Atchison and Sumner and the Missouri side of the river. In 1858, Samuel Hollister built a steam sawmill, adding a gristmill later. The lithograph promotion had worked, and by the end of 1858, Sumner was called home to about 2,000 people — 500 more than Atchison had at the time. The town then took steps toward incorporating, which occurred in 1859.

“The growth of Sumner was phenomenal. A lithograph printed in 1857 shows streets of stately buildings, imposing seats of learning, church spires that pierced-the clouds, elegant hotels and theaters, the river full of floating palaces, its levee lined with bales and barrels of merchandise, and the white smoke from numerous factories hanging over the city like a banner of peace and prosperity. To one who, on that day, approached Sumner from the East and saw it across the river, which like a burnished mirror, reflected its glories, it did indeed present an imposing aspect.”

— H. Clay Park, former editor and part-owner of the Atchison Patriot

However, the decline of Sumner began with a drought that started in the fall of 1859 and prevailed through the following year. In June 1860, a tornado struck the town and blew down or damaged nearly every building. This calamity was followed in September by a visitation of grasshoppers, all of which were potent factors in wiping Sumner off the map.

When the Civil War broke out, the Atchison men who objected to abolitionists settling in their town were driven out of the country, which attracted many of the citizens of Sumner. Many of the businesses and residents soon moved to the larger town, and buildings were moved or torn down, taking the lumber to build others in the county seat. A destructive tornado further damaged Sumner in June 1861, but a few remaining residents held on for a while. The Sumner Gazette was issued until 1861, when it was suspended, and its publishers believed that it was the only paper in Kansas that outlived the town in which it started. The Sumner post office closed in January 1868.

In the meantime, many of the houses had been moved to Atchison, and others to farms in the immediate vicinity. The brick used in the hotel was gathered, cleaned, hauled to Atchison, and used to construct a building owned by John J. Ingalls, located at 108-110 South Fourth Street.

But one last resident would remain until every single building was abandoned—self-proclaimed Sumner Mayor Jonathan Gardner Lang, who lived in the dead town until his death.

Jonathan Lang, alias “Shang,” was born in Kentucky in 1819 and served as a dragoon in the Mexican-American War. At some point, he made his way to Kansas and fought for the cause of pro-slavery. On December 21, 1857, in Marysville, Kansas, he voted 25 times for the Lecompton Constitution before noon. This constitution was drafted by pro-slavery advocates and included provisions to protect slave-holding in the state and to exclude free blacks from its bill of rights.

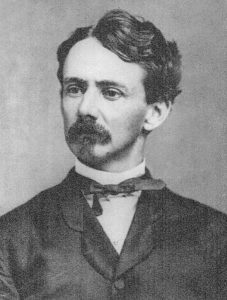

Somewhere along the line, Lang was given the nickname “Shanghai” due to his tall, gaunt form, standing at nearly seven feet. Despite his pro-slavery beliefs, he settled in Sumner in 1858. And there, he met the likes of future Kansas Senator John J. Ingalls. When the future Kansas Senator came to Sumner at the age of 24, he took great interest in the people of the area, including Jonathan Lang, who, at the time, was working as a jug fisherman on the river, as a melon raiser, and a truck patch farmer. Even though Lang also had a reputation for being the town drunkard, Ingalls said Lang was a bright fellow. Ingalls enjoyed Lang’s stories of the West, and Ingalls used to go out in Lang’s boat when he was jigging for catfish and spend hours listening to his talk.

Lang lived on land belonging to Ingalls at the time, and when Ingalls told Lang about it, they settled for a sack of flour and a side of bacon.

Even though Lang supported slavery during the Kansas struggle, he served the Union as a soldier in the Thirteenth Kansas Infantry during the Civil War. However, he was the butt of many jokes from his comrades in camp, and Thomas J. Payne, a sergeant in the Thirteenth, related an amusing story of “Old Shang,” as his comrades generally called Lang.

When the regiment was mustered into service on September 28, 1862, and the newly assigned officers were reviewing their troops at Camp Stanton, in Atchison, Lang’s tall, gaunt form towered above the rest of the men like the stately cottonwood above the hazel brush. Riding up and down the lines and scanning the troops with a critical eye to see that there was no breach of ranks or decorum, the gaze of Colonel Thomas Bowen could not help but fall upon the lofty and lanky form of Lang, rising several heads above the other soldiers. The colonel paused, and pointing his finger at Lane, shouted in thunderous tones, “Get down off that stump.” A ripple of suppressed laughter immediately passed along the lines, and when Colonel Bowen saw his mistake, he promptly revoked his order with a hearty chuckle and rode on towards the end of the column.

Lang continued to serve in the Thirteenth Kansas Infantry, which he led for the next three years under Colonel Bowen’s command. He fought along with the rest of the troops in the First Battle of Newtonia in Missouri in September 1862 and at the Battle of Prairie Grove, Arkansas, in December 1862. He remained with the infantry until the troops were mustered out on July 13, 1865. Afterward, he returned to Sumner.

When his old friend, John J. Ingalls, was the president of the United States Senate, he secured him a pension and back pay for his service. Unfortunately, Lang squandered his pension when he briefly got married.

“Shang” continued to live in Sumner until every house, save his miserable hut, had vanished. He died on December 30, 1887, at the age of 68, and was buried at the Sumner Cemetery. Afterward, lightning struck his old cabin, burning it to the ground.

Today, the old townsite is said to host the ghost of the former mayor and last resident of the town, who allegedly wanders the overgrown site in search of its old residents. The old townsite is on private property and nearly inaccessible except by boat.

Today, the old townsite is said to host the ghost of the former mayor and last resident of the town, who allegedly wanders the overgrown site in search of its old residents. The old townsite is on private property and nearly inaccessible except by boat.

Nothing remains of the old town except for the nearby cemetery. Today, it is utilized as a family cemetery, but it is still active and very well maintained. It is located on 258 Road south of Atchison, Kansas.

“About the time Atchison secured its first railroad, the smoke from the locomotive engines drifted to Sumner and enveloped it like a pall. The decadence was at hand, and Sumner’s race to extinction and oblivion was rapid. One day, there was an exodus of citizens; the houses were torn down, and the timbers thereof carted away, and foundation stones were dug up and carried hence. Successive summers’ rains and winters’ snows furrowed streets and alleys beyond recognition. They filled foundation excavations to the level, and ere long, a tangled mass of briers and brambles hid away the last vestige of the once busy, ambitious city. The forest, again unvexed by ax or saw, asserted his dominion once more, and today, beneath the shadow cast by mighty oaks and sighing cottonwoods, Sumner lies dead and forgotten.”

— H. Clay Park, former editor and part-owner of the Atchison Patriot

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated June 2025.

Also See:

Extinct Towns of Atchison County

Haunted Atchison – The Most Ghostly Town in Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas Cyclopedia, Standard Publishing, 1912

Cutler, William G.; History of the State of Kansas, A. T. Andreas, 1883

Ingalls, Sheffield, History of Atchison County, Kansas, Standard Publishing Company, 1916