By John N. Holloway, 1868

Kansas cannot boast of a remote antiquity. Her soil never became the scene of stirring events until of late years. Her level and far-reaching prairies afforded but little temptation to the early adventurer. No ideal gold mine or opulent Indian city was ever located within her boundary.

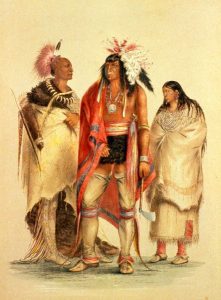

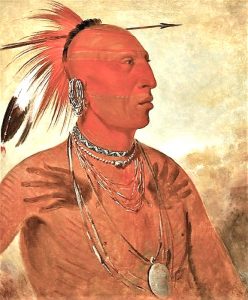

The name Kansas, signifying “smoky,” is derived from the chief river running from the east through the center of the State; the name of the river having been derived from that of the tribe of Indians inhabiting its borders toward its mouth. It was variously spelled by early writers as Cansan, Kanson, and Kanzas; but since the organization of the Territory, it has been written as Kansas. The Kanza Indians were sometimes called the Kaw—a nickname given them by the French.

Kansas Explorations.

In 1705, the French explored the Missouri River as far as the mouth of the Kansas River. The natives received them kindly and soon engaged in profitable trade with them, a relationship that continued for more than a century thereafter. These were the first Europeans who beheld the soil and river of Kansas.

In 1719, Claude Charles du Dutisne, a young French officer, was sent on an exploring expedition by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, the Governor of Louisiana. He ascended the Mississippi River as far as the Sabine River. He then traveled westward over a rocky, broken, and timbered country, about 300 miles as near as he could judge, until he came to the principal village of the Osage Indians. As he described the village, it was situated on a hill five miles from the Osage River and contained approximately 100 cabins. These Indians spent but a small part of their time at the village, being engaged in the chase at a distance.

Traveling then to the north-west, 120 miles, he visits the Panouca. They lived on the prairie, which abounded in buffalo, in two villages of about 130 cabins. They had 300 fine horses, which they highly prized. Then he advanced westward 450 miles to the Pawnee, a courageous and warlike nation. Here, he took formal possession of the country in the name of his King by erecting a cross with the arms of France, September 27, 1719. He then turned back and directed his march to the Missouri River, 350 yards from which he discovered the village of the Missouria. Thus, early on, the French had discovered and explored the Territory of Kansas and had opened a lively trade with the Indians, which was maintained for a century thereafter.

The Spaniards, who always repelled with alacrity every western advance of the French, having driven them from Texas, determined to have command of the Missouri River before their rivals had permanently established themselves upon its border. They had heard of M. Dutisne’s tour through the territory and knew that success required celerity. They sought to possess themselves of the Missouri River, to command its waters and enjoy its commerce by restricting the French on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River. Their objective was first to conquer the Missouria Indians, who lived on the banks of that river and were friendly to the French, and to establish a colony there. The Pawnee, who dwelt west of the aforesaid Indians, were at war with them, and the Spaniards hoped to enlist the former as allies in the undertaking.

Accordingly, a large caravan set out from Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1720 to take possession of the country along the Missouri River and establish a colony on its borders. They first sought the Pawnee villages during their march, but, losing their way, they unfortunately fell in with the Missouria, whom they had planned to destroy. Mistaking them for the Pawnee, they disclosed their designs and solicited their cooperation. The Missouria, manifesting not the least astonishment at this unexpected visit and startling communication, requested time to assemble their warriors. In 48 hours, 2,000 assembled in arms. They attacked the Spaniards in the night and killed the whole party except one priest who escaped on horseback and returned to Santa Fe, where the records of this account were preserved.

This battle occurred slightly below Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on the banks of the Missouri River.

The French apprised of this bold undertaking of the Spaniards in advancing almost 1,000 miles from their possessions into this unexplored country, resolved to establish a fortification in that direction. Accordingly, Etienne Veniard de Bourgmont was dispatched with a considerable force, who ascended the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers to an island in the latter above the mouth of the Osage River, a short distance, and established on it Fort Orleans.

At this time, the Padouca, who lived north-west of the Missouria, were at war with the latter and their allies, the Kanza, Otoe, Osage, and Otoe. In 1724, the aforementioned officer conducted an extensive exploration from Fort Orleans to the northwest, accompanied by a few soldiers and some friendly Indians, to establish friendly relations among the native tribes and to open and strengthen trade with them. Setting out on July 3, he returned on November 5, having accomplished his objective.

In 1804, Lewis and Clark led an expedition up the Missouri River and across to the Pacific under the direction of the Government. They encamped at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers and remained there for two days. Here, they found plenty of game. Somewhere near Atchison, they discovered the remains of an old French fort and village. A little farther up, they found a house and a trading post, but met no white people. An African American cook with them piqued the Indians’ curiosity.

The first steamboat to pass Kansas on the Missouri River was the Western Engineer in 1819, under the command of Major Stephen H. Long. He, with a corps of Topographical Engineers, went on a tour of observation up to the Yellowstone River. “The boat was a small one with a stern wheel and an escape pipe so contrived as to emit a torrent of smoke and steam through the head of a serpent with a red, forked tongue from the bow.” This was designed to imitate a mighty serpent, vomiting fire and smoke, and lashing the water into a foam with its tail, in order to strike terror among the Indians. Tradition holds that they believed it was a “maniteau” that had come to destroy them.

The fur trade was early prosecuted along the Missouri River. In this extensive and lucrative traffic, Kansas must have participated to a large extent. During the 15 years previous to 1804, the value of furs annually collected at St. Louis, Missouri, is estimated at $203,750. James Pursley was the first hunter and trapper to traverse the plains between the United States and New Mexico (1802), and consequently the first Anglo-American to set foot in Kansas. William H. Ashley, in 1823, fitted out his first trapping expedition to the mountains. He discovered the South Pass in Wyoming, thereby opening the route to Oregon and California. For 40 years, the fur trade averaged from $200,000 to $300,000 annually. The last-named gentleman alone, between 1824 and 1827, sent for goods valued at $180,000 to St. Louis, Missouri.

In the spring of 1823, the great Santa Fe trade from Missouri originated at Franklin, now Booneville, in Howard County, where the first enterprise was planned and outfit procured. It being an experimental trip, the stocks conveyed were slender, comprising a cheap class of goods, which were carried on pack mules and in wagons. This expedition, successful and yielding promising prospects for wealth, was repeated the following year on a larger scale. In 1825, the Government, having its attention directed to this new channel of commerce by Colonel Thomas Hart Benton, employed Major George Sibley to survey and establish a wagon road from the Missouri State line to Santa Fe, which has been a great thoroughfare of travel ever since. The trade increased slowly but gradually over the next 22 years, with the value of its exports averaging $50,000 to $100,000 per annum.

The Indian tribes through whose territory the trains had to pass soon became very troublesome. They would suddenly swoop down upon the unsuspecting encampment of the transporters, drive off their draft animals, rob the wagons, and frequently destroy lives. As but few traders in those days started with more than two or three wagons, considerations of safety suggested a general rendezvous. From that point, they could all start together and afford each other mutual protection. A well-timbered and watered spot was selected for this purpose and has since been known as “Council Grove,” Kansas. The caravans that thus collected here numbered hundreds of wagons and thousands of mules, horses, and oxen, and their departures over the Plains were noted in the papers throughout the States.

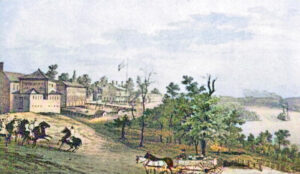

The town of Independence, Missouri, was formed soon after the opening of this overland traffic and became the principal outfitting post. From 1832 to 1848, it held this commercial ascendancy, and its merchants accumulated vast fortunes. In 1834, the first shipment of goods was landed slightly below Kansas City at Francis Chouteau’s log warehouse, destined for the New Mexico trade. From that time, Kansas City and Westport continued to acquire more and more of this overland commerce, so that by 1850, they had secured its monopoly.

According to the record kept by Messrs. Hays & Co. at Council Grove, Kansas, they were engaged in the New Mexico trade in 1860, 5,984 men; 2,170 wagons; 464 horses; 5,933 mules; 17,836 oxen. The wagons were loaded with an average of 5,500 pounds, totaling 6,000 tons. The capital employed in carrying on this transportation for this season alone was not far from two million dollars!

To protect this trade and the western frontier from the depredations of the Indians, the Government in 1827 posted a portion of the Third Regiment of United States troops, numbering about 200 men, where Fort Leavenworth now stands, under the command of Major Baker. This post was named after the Colonel of this regiment, Henry H. Leavenworth. It was at first called a cantonment, and the title of Fort was not applied until 1832. For several years after its establishment, the troops were so severely afflicted by disease that, in 1829, it was temporarily reduced, with most of the troops sent to the prairies. In 1830, the Sixth Regiment of Infantry superseded the Third Regiment of Infantry. In 1835, it was commanded by the Third Division of Dragoons under Colonel Dodge, who, in 1845, made an expedition to Pike’s Peak and back, in which he cultivated the friendship of the Prairie Indians. Fort Leavenworth attracted little attention until the outbreak of the war with Mexico and the gold excitement in California, when it became a major outfitting post for western travel and trade.

Soon after the admission of Missouri as a State into the Union, large cessions of land were secured to the United States from the natives west of that State. The Government then conceived the design and perfected a plan for the transfer of all eastern tribes of Indians to the west of the Mississippi River. Tribe after tribe was thus led to migrate westward, so that by the middle of the 19th Century, no tribe remained in the United States. Thus, until the organization of this Territory, the lands of Kansas were held and inhabited solely by Indians, white people being prohibited by the terms of the treaties from settling on them without the consent of the former. This was literally the Indian Territory, and it was the design of the General Government to make it the permanent home of the Red Man.

Fort Scott was established as a military post in 1841 to contain Indian encroachment. A few Government buildings were erected and sold in 1855 for $200–$300 each. The American Fur Company formerly had a post there.

From 1843 to 1850, General Charles Fremont made repeated tours through this Territory.

The first train that ever crossed the Plains, over the Rocky Mountains, to the Pacific coast, was conducted in 1844 by Mr. Neil Gillem. He set out from Buchanan County, Missouri, with 50 wagons and 100 men, and went to Oregon. The following year, the Mormons assembled near Atchison in preparation for crossing the Plains. They made this their meeting point for all companies traveling to Salt Lake for several years thereafter. They subsequently erected a house here and opened a farm, which is known to this day as the Mormon farm.

In 1845, the Mexican-American War began, and Fort Leavenworth became the staging point for soldiers and the shipping point for military stores destined for Mexico. It was across the prairies of Kansas that General Stephen Kearney made his celebrated march to Santa Fe. Immediately after the termination of this war, gold was discovered in California, and the tide of fortune seekers rolled across this soil. Kansas City, Fort Leavenworth, and St. Joseph were the principal points at which the emigrants united into vast caravans, miles in length, bound for the land of wealth. In 1849, 30,000, and in 1850, 60,000 people crossed the Plains on their journey to the Golden Gate, the chief portion of whom crossed the prairies of Kansas.

As this kind of prairie travel and commerce is passing away, it is thought proper to insert an excellent description of it by one with whom it was perfectly familiar:

“The wagons, after receiving their loads, separately return to the camping places until all belonging to the train are assembled. At that, the order of march is given. A scene then ensues that baffles description. Carriages, wagons, men, horses, mules, and oxen appear in chaotic confusion. Men are cursing, distressing mulish outcries, bovine lowing, form an all but harmonious concert, above the dissonances of which the commanding tone of the wagon master’s voice only is heard. The teamsters make merciless use of their whips, fists, and feet. The horses rear, the mules kick, the oxen baulk. But gradually order is made to prevail, and each of the conflicting elements assumes its proper place. The commander finally gives the sign of readiness by mounting his mule, and soon the caravan is pursuing its slow way along the road.

“The trains reveal their approach at a great distance. Long before getting in sight, especially when the wind carries the sound in the right direction, the jarring and croaking of the wagons, the ‘gee-ho’ and ‘ho-haw’ of the drivers, and the reverberations of the whips, announce it most unmistakably. The traveler coming nearer, the train will by degrees rise into sight, just as ships at sea appear to emerge from below the horizon. The wagons being all in view, the train, when seen a few miles off, from the shining white of the covers, and the hull-like appearance of the bodies of the wagons, truly looks like a fleet sailing with canvass all spread, over a seeming sea. A further advance will bring one up with the train master, who always keeps a mile or so ahead, in order to learn the condition of the roads, leaving the immediate charge of the train to his assistant. On arriving at the caravan itself, one will pass from 25 to 75 high-boxed, heavy-wheeled wagons, covered with double sheets of canvas, loaded with from 5,000 to 6,000 pounds of freight, and drawn by from five to six yoke of oxen, or five spans of mules each. One driver for every wagon is attached to the train. Four to ten additional hands are also available to address potential vacancies. One or more mess wagons, under the superintendence of cooks, likewise form a part of the cortege, the whole being under the supreme command of the wagon master and his assistant. As to cooks, the crew of the prairie fleet, after having traveled on the Plains a week or two, outshine the deck hands of our steamboats altogether. When ‘under sail’ the prairie schooners usually keep about 30 yards from each other, and as each of them, with its animate propelling power, has a length of eighty or ninety feet, a large train requires an hour to pass a given point.”

John N. Holloway, 1868. Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2025.

Also See:

Coming of the Settlers to Kansas

Early Expeditions Through Kansas

Source: History of Kansas, Holloway, John N., Chapter 8, James, Emmons & Company; 1868