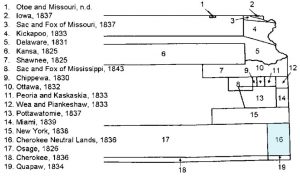

The Cherokee Neutral Land in the southeast corner of Kansas was a disputed strip that comprised all of present-day Cherokee County, nearly all of Crawford County, and a strip about six miles wide across the southern part of Bourbon County. The tract was initially known as the Osage Neutral Land.

The tract, some 50 miles long and 25 miles wide, formed the eastern boundary line separating Kansas from Missouri. It was first described in the treaty with the Osage Indians in 1825, when it was intended to serve as a barrier between the Osage tribe and the white settlers, neither of which was to settle on it, which is how it took the name of neutral land.

Article 2 of the treaty made with the Cherokee at New Echota, Georgia, in 1835, expressed apprehension that not enough land had been set apart for the accommodation of the Cherokee Nation and provided for the conveyance to the Cherokee of “the tract of land situated between the west line of the State of Missouri and the Osage reservation, estimated to contain 800,000 acres.

When this treaty was concluded, the tract was called the Cherokee Neutral Land. Though it was assigned to the tribe, white settlers began to settle the area when Kansas was organized as a territory. In August 1861, the tract was invaded by a Confederate band commanded by John Mathews, and some 60 families were driven out. The following month, the Sixth Kansas Cavalry dispersed the gang, and Mathews was killed.

During the Civil War, pressure increased to open this land for settlement. Squatters began moving onto these lands before the Cherokee Nation sold them to the Federal government.

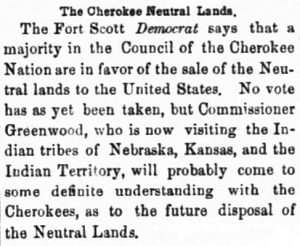

On July 19, 1866, another treaty was concluded between the Cherokee and the United States. Article 17 of the treaty provides:

“The Cherokee Nation hereby cedes, in trust, to the United States the tract of land in the State of Kansas which was sold to the Cherokee by the United States under the provisions of the second article of the treaty of 1835, and also that strip of land ceded to the nation by the fourth article of said treaty, which is included in the State of Kansas; and the Cherokee consent that said lands may be included in the limits and jurisdiction of the said state. The lands herein ceded shall be surveyed as the public lands of the United States are surveyed, under the direction of the commissioner of the General Land Office. Two disinterested persons shall appraise them… And the secretary of the interior shall, from time to time, as such surveys and appraisements are approved by him, after due advertisements for sealed bids, sell such lands to the highest bidders for cash, in parcels not exceeding 160 acres, and at not less than the appraised value… Provided, that nothing in this article shall prevent the secretary of the interior from selling the whole of said Neutral Lands in a body to any responsible party, for cash, for a sum not less than $800,000.”

The last provision was amended to read “that nothing in this article shall prevent the secretary of the interior from selling the whole of said lands not occupied by actual settlers at the date of the ratification of the treaty, not exceeding 160 acres to each person entitled to pre-emption under the pre-emption laws of the United States, in a body, to any responsible party, for cash, for a sum not less than one dollar per acre.”

On August 30, 1866, Secretary of the Interior James Harlan sold the lands to the American Emigrant Company. Two days later, Harlan was succeeded by Orville H. Browning, who set aside the contract with the American Emigrant Company on the opinion of the United States Attorney General that it was void because it wasn’t made on time and not for cash as the treaty stipulated. The settlers on the tract then demanded that Senator Pomeroy and Congressman Clarke use their influence to prevent another land sale. Both made promises, but despite that fact, on October 9, 1867, Browning sold the land to his brother-in-law, James F. Joy, representing the Missouri River, Fort Scott & Gulf Railroad. The railroad company soon began building toward Oklahoma, but they were not the only ones. The Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad was also built, and it became a race between the two companies.

In the meantime, two suits had been filed in the Federal courts — one against a settler named Holden and the other against Dr. Warner, who supported James Joy, with the understanding that the decision in the two cases should settle the title to the lands.

In March 1868, the settlers demanded the right to purchase their holdings at the lawful price of public lands, and the validity of Joy’s title to the lands was questioned everywhere. The American Emigrant Company had not relinquished its claim, and the settlers were alarmed at the prospects of long and tedious litigation before their titles could be assured. Trouble on this score was averted, however, by a supplemental treaty on April 27, 1868, “to enable the Secretary of the Interior to collect the proceeds of the sales of said lands and invest the same for the benefit of said Indians, and to prevent litigation and of harmonizing the conflicting interests of the said American Emigrant Company and of James F. Joy.”

Technically, the treaty set aside the Joy sale but authorized the assignment of the American Emigrant Company’s interests to Joy. Eugene F. Ware said:

“This was necessary so as to scoop in the land occupied in the meantime by about 3,000 people under the public land law. The law gave a homestead on five years’ occupation, but service in the army was counted in, and the soldier who had served three years got title in two years, but with the right to buy the land at $1.25 per acre. The ‘treaty’ ratified by the Senate cut off these rights from all settlers coming in after July 19, 1866.”

The United States Senate ratified the supplemental treaty on June 6, 1868, when the interests of the American Emigrant Company were assigned to James F. Joy. Four days later, the president proclaimed the treaty.

On December 18, 1868, notice was given to all persons “who had settled and continued to live on the lands between August 11, 1866, and June 10, 1868, that they might make entry of the lands before a certain time, and thus prevent the sale of the lands to other purchasers.”

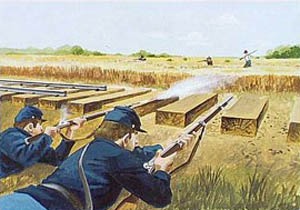

The railroad survey commenced early in 1869, and the trouble began earnestly. Facing the prospect of losing their land, settlers banded together to form the “Land League” to resist the encroachments of a corporation under what they believed to be an illegal sale of public lands. At first, the principal objective of the organization was to keep a delegate in Washington to look after the interests of the settlers. Still, things got worse as the railroad company became more aggressive in prosecuting what it conceived to be its legal rights.

A land office established at Baxter Springs by Joy was raided in February 1869. In April, when J. W. Davis attempted to open a land office for the railroad company at Columbus, he was given notice to leave the town — a mandate he lost no time obeying. In May, members of the league assaulted a survey crew and burned their equipment.

The situation became so threatening that Governor James Harvey sent a detachment of United States troops into the Neutral Lands on June 10, 1869, to preserve order and protect the railroad workers. However, league members attacked a railroad construction camp and notified the workers that they would burn them out in July.

The Post of Southeast Kansas was created on January 14, 1870, with its headquarters in Fort Scott, but the troops were stationed in camps along the right of way. Early in the legislative session of 1870, the House appointed a committee of five to visit the troubled district and ascertain if the presence of soldiers was necessary. Most of the committee reported favoring the governor and recommended keeping the troops there until the question was settled.

The presence of the troops angered the settlers further. They considered the soldiers to be the puppets of the railroads and viewed them with distrust. They had initially asked for military protection for themselves and now felt betrayed that the troops were protecting the railroad instead. The military presence testified to James Joy’s influence on the government.

In May 1870, the circuit court favored James Joy and the railroad. Notwithstanding the court’s decision and the soldiers’ presence, the anti-Joy people burned the office of the Girard Press on July 15, 1871. This paper was edited by Dr. Warner, who had been employed by Joy to publish it in support of his claim. In response, 20 soldiers were sent to Girard to protect the publisher from further threats.

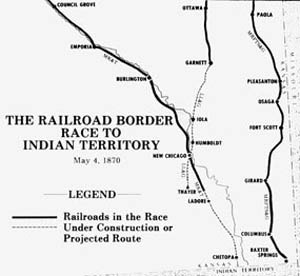

Railroad Race.

However, the settlers were not the only ones engaged in destructive behavior. In September 1871, near the end of a 230-mile trip, the soldiers of Company A, 7th Cavalry, destroyed a considerable amount of property as they passed through Chetopa, Kansas. Soon after, a few soldiers got too lively in Columbus and were locked up. In the process, some friends broke them out and exchanged gunfire with the local police.

An appeal to the United States Supreme Court was taken, and in November 1872, that court, in a unanimous opinion, upheld the lower court’s decision.

The settlers then bought their lands through Joy, and the troops were withdrawn in February 1873. As required, the proceeds were placed in the United States Treasury subject to the order of the Cherokee National Council.

In the end, the Missouri River, Fort Scott & Gulf Railroad did not reach Oklahoma first; the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad won the race.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, 1912

National Park Service