Locusts.

An invasion of grasshoppers began in July 1874 when millions of insects, more accurately called Rocky Mountain locusts, descended on the prairies from North Dakota to Texas without warning. They arrived in swarms so large they blocked out the sun and sounded like a rainstorm.

After the Civil War, many settlers came to Kansas and other parts of the Great Plains to find inexpensive land and a better life. These new settlers broke the prairie ground, planted crops, and built homes in no time.

The spring of 1874 provided good rains, and the farmers looked forward to the harvest in Kansas. However, that summer, the Midwest was engulfed in a drought. Unfortunately for the farmers, this drought set up ideal conditions for the Rocky Mountain locust. Their natural habitat was drier than usual, so they had to move east to find food.

In late July, without warning, millions of Rocky Mountain locusts from the mountains of Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana descended upon the prairies. Arriving in swarms so large they blocked out the sun, they spread across the Great Plains from Canada in the north to Mexico in the south, and in a few hours, they ate crops down to the ground. One farmer reported that the locusts seemed “like a great white cloud, like a snowstorm, blocking out the sun like vapor.” Confronted with a sudden invasion, farmers rushed to cover their wells and scrambled to save what crops they could by covering their gardens with blankets and textiles, but the insects’ numbers were too great, and they chewed through the fabric.

After eating the crops, they moved on to consume the wool from live sheep, clothing from people’s backs, paper, tree bark, sawdust, leather, and even wooden tool handles, which were completely devoured. A visit to a farm could last two days to a week, leaving behind a devastation that appeared as if the land had been destroyed by fire. Freshly planted young crops were especially vulnerable to the locusts, and newly arrived emigrants in western Kansas were hit the hardest. In many cases, the insects were said to have covered the ground several inches deep, and locomotives could not get traction because the insects made the rails too slippery. These small grasshopper-like locusts measured about one-and-one-quarter to one-and-one-half inches long.

These ravenous insects also knew no bounds, infiltrating every nook and requiring residents to pat down their bedding before retiring.

“They beat against the houses, swarm in at the windows, cover the passing trains… They work as if sent to destroy.”

— New York Times correspondent.

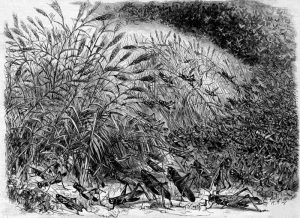

A field devastated by grasshoppers.

Unfortunately, not everyone survived.

“We have seen within the past week families that had not a meal of victuals in their house; families that had nothing to eat save what their neighbors gave them, and what game could be caught in a trap since last fall. In one case, a family of six died within six days of each other from the want of food to keep body and soul together… From present indications, the future four months will make many graves, marked with a simple piece of wood with the inscription STARVED TO DEATH painted on it.” — St. Louis Republican

The report of the Kansas State Board of Agriculture for 1874 stated:

“About July 25, one of those periodical calamitous visitations to which the trans-Mississippi states are liable once in from eight to ten years made its appearance in northern and northwestern Kansas — the grasshopper or locust. The air was filled, and the fields and trees were completely covered with these voracious trespassers. At one time, the destruction of every green thing seemed imminent. Their course was in a southerly and southeasterly direction, and before the close of August, the swarming hosts were enveloping the whole state. The visitation was so sudden that the people of the state became panic-stricken. In the western counties — where immigration for the last two years had been very heavy, and where the chief dependence of the new settlers was corn, potatoes, and garden vegetables — the calamity fell with terrible force.”

Starvation or emigration appeared to be the only alternatives for the people of the ravaged districts. In this emergency, Governor Thomas A. Osborn called a special legislature session on September 15, 1874, hoping to find a way to help Kansans survive the calamity and relieve the destitution left by the grasshoppers. In his message, the governor gave a list of the counties devastated by the grasshoppers. Those most seriously affected were Norton, Rooks, Ellis, Russell, Osborne, Phillips, Smith, McPherson, Rice, Barton, Reno, Edwards, and Pawnee. Still, in several other counties, varying degrees of damage had been wrought. The legislature approved $73,000 in bonds to provide aid, and a plea for more help went out across America. The nation responded to the pleas for aid by sending money and supplies, often hauled for free by the railroads. On the evening of November 19, 1874, a meeting was held in Topeka. The “Kansas Central Relief Committee” was organized with Lieutenant Governor E.S. Stover as chairman and Henry King, editor of the Topeka Commonwealth, as secretary. Soon, the railroad companies were transporting aid to the destitute farmers across the state, delivering barrels, boxes, and bales of supplies such as beans, pork, rice, and seed to assist Kansans with the following year’s planting. The committee received and disbursed cash of $73,863.47; besides 265 carloads and 11,049 packages of supplies, the total value of the assistance rendered was $235,108.47. This included 32,614 rations and clothing for 8,077 men, 9,758 women, and 16,452 children.

“This visitation of grasshoppers, or locusts, was the most serious of any in the history of the State. They reached from the Platte River, on the north, to northern Texas and penetrated as far east as Sedalia, Missouri. Their eggs were deposited in favorable localities over this vast territory. The young hatched the next spring and did great damage to early crops, but in June, having passed into the winged state, they rose into the air and flew back to the northwest, whence their progenitors had come the year before.”

— Daniel W. Webster,Annals of Kansas, 1886

Though this was not the first time the locusts had swarmed in the Great Plains, this was the worst year. They had appeared in the country west of the Mississippi River, practically destroying every green thing on their line of March. In 1818 and 1819 in Minnesota, John Schoemakers of the old Osage Mission in Kansas wrote of some damage done by grasshoppers in the fall of 1854, and John G. Pratt of the Delaware Baptist Mission in Kansas reported grasshopper swarms in 1867.

Unfortunately, the locust plague did not end in 1874, as it re-emerged the following April as an even worse plague in counties and states further east. The following two years saw more infestations, but they were much less severe than in 1874 and 1875.

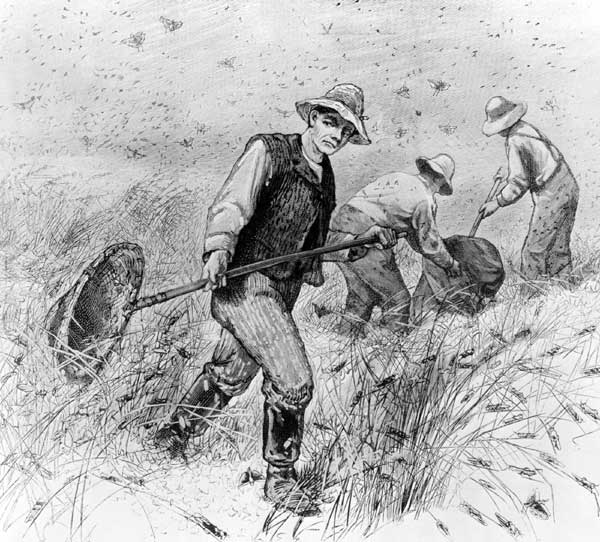

Sweeping a field crop for grasshoppers on a Finney County, Kansas farm. Metal teeth went through the crop, making the grasshoppers jump up, hit the back wall, and drop into a container by Henry L. Wolf about 1895.

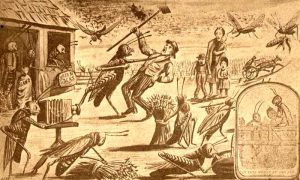

In March 1877, the Kansas State Legislature passed an act authorizing township trustees and the mayors of cities not included in any township, when requested in writing by 15 legal voters in such township or city, to direct the road overseers to warn out all able-bodied males between the ages of 12 and 65 years, to destroy grasshoppers. However, men over 18 could pay a dollar a day to be exempt from such work, but failure to answer the call or pay the stipulated amount subjected such a person to a fine of three dollars a day. When the grasshoppers appeared in the western counties in 1911, there was talk of reviving this law, but the scourge was insufficient to render it necessary.

Other states also required people to work. In Missouri, the government stated that all able-bodied men between the ages of 16 and 60 dedicate one or two days per week to plowing and killing locust eggs and larvae, and offered a bounty of $1 a bushel for locusts. In Minnesota, Nicollet County paid its citizens $25,053 for delivering 25,053 bushels of slaughtered locusts. In Nebraska, the law required everyone to work at least two days, eliminating locusts at hatching time or face a $10 fine. Other Great Plains states made similar bounty offers.

As a whole, Kansans refused to be defeated. The settlers did their best to stop the hoppers by raking them into piles and burning them, but these efforts were in vain because of the sheer number of pests. Inventive citizens also built “hopper dozers,” horse-drawn tools that trawled fields, using a steel plate covered in sticky coal tar to scoop and trap locusts from the ground. They also developed grasshopper harvesters to combat future visitations.

Between 1873 and 1877, the locusts caused $200 million in crop damage in Colorado, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, and other states, covering an area equal to the landmass of California. In one year, 12 trillion locusts devastated the Great Plains, with the weight of all the bugs in the swarm estimated to be more than 27 million tons.

In the 1880s, farmers had recovered enough to send carloads of corn to flood victims in Ohio. They also switched to such resilient crops as winter wheat, which matured in the early summer before locusts migrated. These new agricultural practices effectively reduced the threat of locusts.

Then, as suddenly as it started, the Rocky Mountain locust began to disappear mysteriously. One theory suggests that the combination of plowing and irrigation by settlers, along with trampling by cattle and other farm animals near streams and rivers in the Rocky Mountains, led to the destruction of their eggs in the areas where they permanently lived, ultimately causing their demise. New agricultural practices also contributed to the species’ downfall. Some speculate that the plowing of the prairie or a series of wet years disrupted their egg-laying.

The Rocky Mountain Locust is extinct today. The last sighting of one was in 1902.

“You could hear the millions of jaws biting and chewing… Grasshoppers went into the house with them. Their clothes were full of grasshoppers. Some jumped into the hot stove where Mary was starting supper. Ma covered the food till they had chased and smashed every grasshopper. She swept them up and shoveled them into the stove.”

— Laura Ingalls Wilder, On the Banks of Plum Creek

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Dodge City Globe

Kansapedia

Timeline.com

Wikipedia