Towns & Places:

Caney

Cherryvale

Coffeyville

Dearing

Elk City

Havana

Independence – County Seat

Liberty

Sycamore

Tyro

One-Room, Country, & Historic Schools of Montgomery County

Elk City Lake

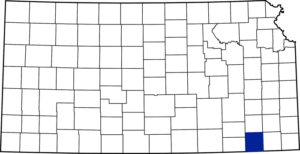

Montgomery County, Kansas, is located in the southeast part of the state. The county seat is Independence, and its most populous city is Coffeyville. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 31,486.

In 1854, the Kansas Territory was organized, and in 1861, Kansas became the 34th state of the United States. Montgomery County was formed from Wilson County on February 26, 1867, and named in honor of General Richard Montgomery, who was killed in action during the American Revolution.

Located in the southern tier of counties, Montgomery County is the third west of the Missouri line. It is bounded on the north by Wilson County, on the east by Labette County, on the south by the State of Oklahoma, and on the west by Chautauqua and Elk Counties.

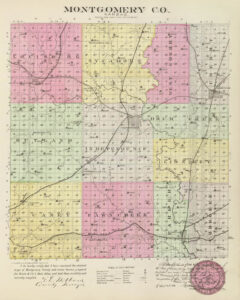

The county’s general surface is prairie. The bottomlands along the creeks and rivers averaged more than a mile in width and accounted for 25% of the area. The timber belts on the streams averaged a few rods in width. They contained trees such as walnut, cottonwood, hickory, oak, pecan, hackberry, ash, mulberry, sycamore, elm, maple, boxelder, and locust. The Verdigris River entered from the north and flowed south into Oklahoma. The Elk River entered the northwest and flowed east, joining the Verdigris River. Big Hill, Drum, Pumpkin, Sycamore, and Onion are important creeks.

The Osage Indians were the first settlers on the southeast corner of the Kansas plains in what would later become Montgomery County. As early as 1803, Chief Black Dog and his band of Osage Indians made a trail through present-day Coffeyville to hunt buffalo.

Montgomery County was created on February 26, 1867.

Among the settlers of 1868, all of whom located along the river and creek valleys in the eastern part of the county, were John A. Twiss, T.C., J.H., and Allen Graham, J. H. Savage, Jacob Thompson, E.K. Kounce, William Fain, Green L. Canada, W.L., and G. W. Mays, John L. McIntyre, and Joseph Roberts. John Russell, J.B. Rowley, Patrick Dugan, William Reed, Christian Greenough, John Hanks, Mortimer Goodell, D. R. B. Flora, R. W. Dunlap, Mrs. E. C. Powell, Thomas C. Evans, Lewis Chouteau, George Spece, and James Parkinson.

Several disasters in the way of fires and floods have occurred in the history of Montgomery County, but perhaps none was so picturesque as the prairie fire of 1868. A long spring drought was followed by an exceptionally wet summer. The rivers and creeks were swollen so that they were impassable, and the ground was soaked so that no crop could be raised. Wild grass grew rank all over the county, and when this became dry, a terrific but magnificent conflagration swept the county. While it lasted, it kept the skies bright at night so that in the light of the fire, one could read ordinary handwriting at a distance of a mile or more from the blaze. Livestock, utensils, settlers’ cabins, and whole villages were destroyed, and several lives were lost.

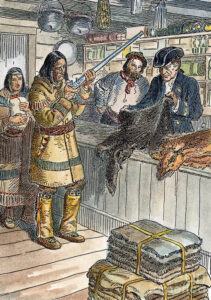

Colonel James A. Coffey started an Indian trading post in 1869. The same year, Major Fitch opened another store on the north side of Elk Creek near the mouth of Sycamore Creek. To obtain a “squatter’s claim,” the settler had to secure the consent of the Indians, which, by a treaty made in the Upper Elk Valley in 1869, was to be had on payment of $5 for a prairie claim and $10 for one in the timber.

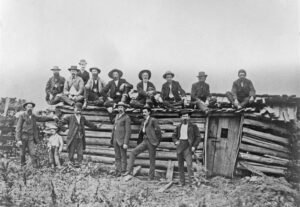

Considerable trouble arose between the settlers and the railroads over title to the lands in the eastern part of the county. The matter was finally settled in favor of the settlers by the United States Supreme Court. The unreliability of the early surveys caused some confusion about ownership of certain tracts of land after the authorized survey was completed. Unwilling to await the tedious and often expensive process of law on these matters, there were formed in different parts of the county called “Settlers Claim” clubs, to which all disputes of this character were referred. A code of laws was drawn up to cover all points that could arise in any dispute over land title. All cases were settled according “to law and evidence,” and whenever a decision had been reached, the party against whom such decision had been rendered was given notice to move from the claim within a certain length of time. Upon failing to obey, he was forcibly ejected from the premises, and his buildings and other property were destroyed. Occasionally, these clubs took a hand in criminal cases, as in the punishment of the three murderers of John A. Twiss, who were hanged from an oak tree after a trial by the club.

The county was organized in 1869 by Governor James Harvey’s proclamation. Verdigris City was named the temporary county seat, and the following officers were appointed: Commissioners H.C. Crawford, H.A. Bethuran, and R.L. Walker; Clerk E.C. Kimball. The commissioners divided the county into three townships: Drum Creek, Westralia, and Verdigris. An election for county officers and to locate the county seat was held in November of the same year. The returns from Drum Creek were thrown out on technical grounds, and the remaining vote gave a majority for Liberty. A board of commissioners favorable to that place was elected. Independence filed a notice of contest, and the matter was taken before the court of Wilson County, to which Montgomery was attached for judicial purposes at that time. The court decided that there had been no election. Despite significant opposition, the old board of commissioners continued to serve, but the county seat was removed to Liberty. The Independence men sent Charles White to Topeka, Kansas, to lay the matter before the state authorities. He appointed a new board of commissioners composed of W.W. Graham, Thomas Brock, and S.B. Moorhouse. The new board went to Verdigris City, where they organized and appointed the following officers: County Clerk, J.A. Helpingstine; Treasurer, Samuel Van Gundy; Register of Deeds, J.K. Snyder; Superintendent of Schools, R.B. Cunningham. They selected Independence as the county seat and, finding it useless to dissent, the old board gave up the fight. At a hotly contested election in November 1870, Independence received the largest number of votes and became the permanent county seat. The courthouse, erected shortly afterward, was the first brick building in the county.

The county was divided into 12 civil townships: Caney, Cherokee, Cherry, Drum Creek, Fawn Creek, Independence, Liberty, Louisburg, Parker, Rutland, Sycamore, and West Cherry.

The county was settled to some extent before 1870, though the lands still belonged to the Osage Indians until the Drum Creek treaty in September of that year. However, a narrow strip, three miles wide, along the eastern side was part of the “ceded lands,” which were opened to settlement in 1867. In that year, the first settler, Louis Scott, an African American, located in the Verdigris Valley. In December 1867, Zachariah C. Crow, P.R. Jordan, and Colonel Coffey settled in the same neighborhood. In February 1868, R. W. Dunlap established a trading post near the mouth of Drum Creek, and about the same time, a post was established by John Lushbaugh at the junction of Pumpkin Creek with the Verdigris River. That winter, Moses Neal opened a store at the mouth of Big Hill Creek.

Reckless and extravagant bond issues followed the organization of the county government. Before 1872, the people had incurred, for various purposes, a debt of nearly $1,000,000. Money loaned to private parties drew interest rates of 25 to 50%. The people were very anxious for a railroad. In 1870, they voted $200,000 in bonds to the Leavenworth, Lawrence & Galveston company, which built a line through the eastern part of the county terminating at Coffeyville. Independence, indignant at being deserted by the railroad company, after being foremost in securing the bonds, yet over-zealous for a road, paid the company an immense bonus to build a branch. This was called “Bunker’s Plug” and was in use from January 1872 to 1879. In the latter year, the South Kansas & Western built a line across the county, connecting with the main line at Cherryvale. The following year, the St. Louis, Warsaw & Western Railroad built a line across the northeastern part of the county. At that time, there were 65 miles of railroad in the county.

Coffeyville was first incorporated in 1872, but the charter was declared illegal, and the city was re-incorporated in March 1873. The area between 13th and 15th Streets on Walnut became the central trading hub with the Indians. Commerce quickly boomed in Coffeyville.

In 1873, settlers near Cherryvale made a gruesome discovery. Travelers had been going missing, and suspicions began to arise, especially after the disappearance of a man named Loncher, his daughter, and Dr. William York. The surrounding area was searched, and it was discovered that the Bender family’s property was abandoned. Upon inspection, several bodies were discovered. The Bender family, John Bender Sr., Ma Bender, Kate Bender, and John Bender Jr., had settled in the Labette County area, near the Montgomery County line, along the Osage Mission Independence Trail. As travelers stopped at their store and inn, they would rob and murder them. They would sometimes even murder people who had nothing of value. The victims were hit with a hammer as they sat near a canvas. The Bender murders were a family effort, and the family mysteriously disappeared when suspicions arose. Despite many theories and rumors, what happened to them is unknown.

In 1874, Montgomery County, in common with the whole state, fought the grasshoppers.

By 1876, the town had eight general stores, two hardware stores, two banks, two drugstores, two bakeries, three hotels, two livery stables, three blacksmith shops, two gristmills, a school, and two churches.

In the 1880s, Coffeyville was known as a cowtown because of the large number of cattle grazing on the open range, its role as a shipping hub for livestock, and its status as one of the most important grain and flour-milling centers in the Central West.

A Board of Trade was established in 1884.

The next most disastrous occurrence was the 1885 flood in the Elk and Verdigris River valleys, when homes were inundated, and many lives were lost.

The Montgomery County Courthouse was built at 217 East Myrtle Street/North 6th Street in Independence, Kansas. 1886-1887. The courthouse was completed on December 1, 1887, for $54,156.

The discovery of oil and gas in 1890 was one of the most significant long-range events in the county’s history.

Early on the morning of October 5, 1892, the Dalton Gang rode into Coffeyville shortly after 9:00 a.m. to find the city’s streets filled with people. Tying their horses in an alley across from the banks, they dismounted and marched down the alley, three in front and two in the rear. The outlaws, disguised with false beards, divided into two groups: Grat Dalton, Bill Power, and Richard “Dick” Broadwell entered the C.M. Condon & Co. Bank, while Bob Dalton and Emmett Dalton crossed the plaza to enter the First National Bank. All but Emmett would die in the failed robbery.

The waterworks plant was built in 1895 for $49,000.

In 1896, the Coffeyville Commercial Club, an early version of the Chamber of Commerce, began strengthening the city’s municipal and commercial aspects. The club’s early members were men of means and vision who were staunchly dedicated to Coffeyville’s growth and willing to stake their own fortunes to make it happen. The founding board members had several ideas to spur growth, including installing necessary electric streetlights, city waterworks, and a power plant. A marketing pamphlet was created as early as 1899, giving Coffeyville the nickname “Gateway City to the Southwest,” highlighting that three railroad lines traversed the city: the Missouri Pacific, Katy, and Santa Fe. The group also raised $100,000 from townsfolk to attract industry. They used it in combination with their own funds to buy land that they could, in turn, sell to new businesses at a low price. The group’s efforts paid off. Brick buildings and sidewalks began to replace frame structures and dirt paths.

Economic growth was partly due to ingenuity, hard work, and abundant natural resources. In the vicinity of Coffeyville, large deposits of clay, sand, and shale were discovered. As the 19th century came to a close, William P. Brown noticed a gas odor on the property where his lumber company was located. Within six months, he discovered one of the country’s most significant natural gas sources. The local gas and oil reserves, combined with shale and clay, led to the town’s rapid expansion into an industrial city.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Coffeyville had ten glass factories and five brick-and-tile plants. The 1901 population of 5,000 increased more than threefold in five years to 18,500. Coffeyville became home to both blown-glass factories and bottle-glass factories, providing 2,000 jobs and a $2 million annual payroll. The industry helped foster the boom during its tenure from 1901 to 1916, when highly skilled glass blowers came from other states to work in the glass factories. The Coffeyville Window Glass Company, the Sunflower Glass Plant, and the Mason Fruit Jar Plant called the city their home. The Mason plant produced approximately one-third of the world’s supply of Mason Fruit Jars during its three-year tenure between 1904 and 1906. By 1905, Coffeyville had 36 blocks of brick-paved streets. A regional train called the “Interurban Line” was laid, connecting Coffeyville to Nowata, Independence, and Parsons.

The Coffeyville Window Glass Company employed 175 to 200 workers and marketed $200,000 worth of glass products annually. Over 700,000 feet of lumber were used to make boxes to ship the glass. Four glass companies had moved their production to other states by 1916, while the remaining six had ceased operations. When Coffeyville’s brick factories were operating at capacity, about 765,500 bricks were made daily by the four primary companies: Coffeyville Shale and Brick Company, Standard Brick Company, Vitrified Brick Company, and Yoke Brick Company. During the same era, a pottery and stoneware company manufactured 85 different sizes and shapes of stoneware.

In 1910, there were 160 miles of railroad tracks. By then, the early companies had sold out, and the roads’ names had been changed. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad entered the northeast corner, passed southwest through Cherryvale and Coffeyville, and continued into Oklahoma. A branch of this line diverged at Cherryvale and ran southwest through Independence and into Chautauqua County. There were three lines of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. One entered the north and ran south through Independence to Dearing, where it merged with a second line that crossed the southern part from east to west. The third line crossed the northwest corner. The St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad entered near the northeast and ran to Cherryvale, where it split into two branches, both of which ran to the Joplin-Galena lead and zinc district. The Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad crossed the southeast corner.

At that time, there were post offices in Bolton, Caney, Cherryvale, Coffeyville, Dearing, Elk City, Havana, Independence, Jefferson, Liberty, Sycamore, Tyro, and Wayside.

While not strictly an agricultural county, the farms’ yearly product brought in over $2 million. In 1910, the wheat crop was worth $200,000; corn, $650,000; Kafir corn, $112,000; oats, $250,000; and prairie grass, $150,000. There are 150,000 bearing fruit trees. Livestock was raised to a considerable extent. The population, according to the 1910 census, was 49,475, representing an increase of more than 20,000 in ten years. The assessed valuation of the property in that year was $60,650,000.

The power plant received upgrades in 1916, designed by local architect Clare A. Henderson, for $20,000. Additional improvements were made in 1922 and 1923, funded by the plant’s profits.

In the 1920s, the glass and brick industries were overtaken by the oil and gas industry. The Sinclair Refining Corp. of Independence bought out some of Coffeyville’s smaller firms and expanded production. Other small industrial and manufacturing interests found a home in Coffeyville, keeping the economy humming through the 1920s. Additionally, city building continued throughout the decade with the construction of numerous new public and private buildings, including Roosevelt Junior High School, Hotel Dale, the Christian Church Auditorium, the Brighton Furniture Store, the Coffeyville Journal Building, and Memorial Hall, as well as the new Municipal Building and Courthouse.

For decades, the Civil Rights movement was fought in the courts, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation was unconstitutional. One such case was Thurman-Watts v. The Board of Education of Coffeyville, which dealt with segregation in Montgomery County in 1924.

The present-day Montgomery County Courthouse and Municipal Building was built in Coffeyville in 1929. An excellent example of 1920s civic architecture, it serves a unique dual function as both a city hall and a district court in a non-county-seat community. The building was distinguished in municipal realms because it was financed with proceeds from the city’s electric and light plant, without a cent of tax dollars. This fact was particularly significant, given that the building was completed just after the 1929 stock market crash. The building was built in the Classical Revival style, a popular choice nationwide for monumental civic and institutional buildings during the City Beautiful Movement. The building maintains a significant degree of historic and architectural integrity. Its interior retains its marble-clad rotunda, terrazzo staircases, coffered plaster ceilings, and pendant light fixtures. The exterior of the building embodies the dominant characteristics of the Classical Revival style, including symmetrical facades with central entrances, a prominent cornice band, massive Doric columns and pilasters, and delicately carved terracotta and stone panels. The period of significance for Coffeyville’s Municipal Building and Courthouse begins with its construction in 1929. It extends to 1966, the 50-year threshold the National Park Service established for evaluating historic significance. It is located at 102 W. 7th Street in Coffeyville.

The Great Depression, which began in 1929, was not absent in Coffeyville, but the strength of a diversified economy allowed its citizens to weather the storm. Coffeyville, with a broad spectrum of industries such as glass-blowing, oil, brick making, clay, shale, sand, and pottery stoneware, helped ease the pain of the 1930s Depression. While it was still difficult, the community fared better than other places.

In June 1931, an overall redesign of the courthouse began. The original clock tower and part of the west entrance were removed at that time. The new design called for a new north wing. A veneer of smooth-cut Bedford stone covered the structure. The remodeling cost $159,476. It is a T-plan building with a rectangular front block and rear wing. The building has two stories plus a basement. The jail is located above the rear wing. It features a flat parapeted roof, double-hung windows, and metal entrance doors on the South, North, and Southeast sides. There is a furnace stack at the southwest corner of the rear wing. Decorative elements include the two main recessed entries, ornamented with columns, copper transom grills, carved doorframes and hoods, and a projecting carved eave cornice.

While the economy slowed in the early 1930s, by 1936, Coffeyville’s businesses were expanding again. The Nutrena Mills increased output by 50%; A & P Grocery enlarged its store, and the regional Fadler Produce Company opened a branch in Coffeyville.

Little House on the Prairie, written by Laura Ingalls Wilder, was published in 1935. It is the third book in her series, which presents a fictionalized account of her childhood and young adult life. Little House on the Prairie tells the fictionalized account of how her family moved to Kansas, near Independence in Montgomery County. They eventually left, though, as they faced being forcibly removed, as the land belonged to the Osage and had not opened for white settlement as had previously been believed would happen.

Like many cities throughout the Midwest, Coffeyville gave its all during World War II. As its skilled workers began leaving for volunteer service in 1940, the Chamber of Commerce teamed up with industries across the tristate region to lobby their congressional representatives to secure the placement of war industry in the area. Businesses sought means to support the growing Kansas aircraft industry. Coffeyville Junior College began training aircraft machine shop workers, and a local company, Jensen, bought out a small aircraft firm. By 1941, seven local plants had defense-related contracts. Coffeyville Army Air Field was established northwest of town in 1942 and used to train pilots throughout the war. The airfield was closed in 1946. As the war ended, the city began to focus on modernization, and in 1946 alone, more than $675,000 was spent on local utility upgrades and $70,000 on downtown remodeling.

In the 1950s, the light industry grew when the Coffeyville Packing Company built two new concrete buildings, and Continental Can Company built a new plant in town. Acme Foundry, a Coffeyville business since 1914, added 6,000 square feet of factory space in 1952. City construction projects topped 1.4 million dollars in 1953.

From 1955 to 1969, building permits totaled over $15 million, with 1968 reaching a peak of $3 million. Coffeyville’s population was just over 17,000 in 1968, but stagnated in the following decades.

Following an amendment to the Kansas Constitution in 1986, the county remained a prohibition, or “dry,” county until 1998, when voters approved the sale of alcoholic liquor by the individual drink without a food sales requirement.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 651 square miles, of which 644 square miles is land and eight square miles is water. The lowest point in Kansas is located on the Verdigris River in Cherokee Township, Montgomery County, just southeast of Coffeyville, where it flows out of Kansas into Oklahoma. Western portions of the county lie within the northern Cross Timbers eco-region, which separates the forested eastern United States from the Plains.

Montgomery County has several properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places and the Kansas Register of Historic Places. The Cherryvale Carnegie Free Library, Coffeyville Carnegie Public Library, and Independence Carnegie Library are examples of public libraries established with the help of Andrew Carnegie and the Carnegie Corporation. The Kansas Rock Art nomination, which includes sites of Native American art, contains 30 total sites, including petroglyphs and pictographs. Montgomery County contains four petroglyph sites. The Coffeyville Municipal Building and Courthouse were opened in 1929.

The Independence Downtown Historic District primarily comprises the core downtown area of Independence, Kansas. The district comprises 115 buildings, which are mainly Neo-Classical, Classical Revival, and Commercial styles. There are two homes included in the district. One of these is said to be the oldest surviving home in Independence. Virtually all of the buildings in the district are constructed of brick, concrete, stone, or a combination of these materials.

Independence, Kansas, courtesy of Google Maps.

Neewollah, which is Halloween spelled backward, is held in Independence six months after Halloween each year and is billed as Kansas’s largest celebration.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated January 2026.

Also See:

Kansas Counties

Kansas Destinations

Sources:

American Courthouses

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Cutler, William G.; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.

Kansapedia

Wikipedia