Pappan’s Ferry was a major crossing of the Kansas River for travelers on the Oregon–California Trail in present-day Topeka, Kansas. The ferry was established in 1843, eleven years before Kansas was officially opened for settlement.

In the spring of 1840, brothers Joseph and Ahcan Pappan, with their wives, moved from Missouri to Kansas, and the following year, they were joined by another brother, Louis Pappan, and his wife. The three French Canadian brothers — Joseph, Ahcan, and Louis had emigrated from Montreal with their father and settled in St. Louis, Missouri, in the latter part of the 18th century.

Joseph, Ahcan, and Louis Pappan married Josette, Julie, and Victoire Gonvil, respectively, whose father, Louis Gonvil, was a French trader. Their mother was a Kanza Indian. These three women, by the terms of the treaty made with their tribe in 1825, were each entitled to a section of land on the north bank of the Kansas River in present-day north Topeka.

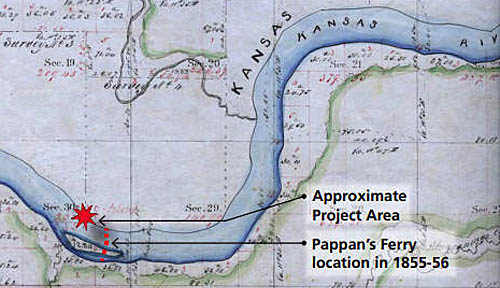

In 1842, the brothers established the first ferry across the Kansas River, just above the island onto which the Topeka City reservoir was later built. This was at the foot of Western Street on the river’s south bank.

Known as Pappan’s Ferry, it was made of two or three dugouts joined by a log platform capable of transporting only one wagon at a time. A rope guided the craft from shore to shore while the ferryman propelled the boat with a long pole. It was started to accommodate travel between Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, on the Santa Fe Trail. Between 1841 and 1863, Oregon and California-bound travelers used the ferry to cross the broad, deep, and swift river.

The Pappans lived in a cabin near the river, and the passengers often lay down in the grass at the site to sleep until morning when business began.

The ferry charge was $1 per wagon. Their ferry crossing operation was invaluable and profitable, making a successful living for the family in the following years.

“We proceeded through a beautiful woodland of oak, ash, walnut, sycamore, quivering asp, hazel, grape vines, and a variety of under-growth which skirts both sides of the Kansas River, about half a mile on either side. Passing there three miles and a half through a level and rich prairie, well covered with nutritious grass, we encamped for the night on the bank of a small creek, a tributary of the Kansas, having traveled eight miles during the day.”

— West-bound Pioneer on the north side of the Kansas River, 1948

On May 30, 1854, President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which proved to be a momentous event in the destinies of this nation, allowing the citizens of this new territory to decide the question of whether Kansas would enter the Union as a Free State or a slave state.

On December 5, 1854, nine men gathered in a makeshift log cabin on an open prairie at the banks of the Kansas River near Pappan’s Ferry. These gentlemen formed the Topeka Town Association and chose Cyrus K. Holliday as their leader. He helped to found the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, and the Merchants Nation Bank and served as Mayor several times. Because the legislation allowed the citizens to decide the question of a free state or slave state, these nine men agreed the new town would be a free-state haven. The Association selected the name Topeka on January 1, 1855, and to name the streets after the Presidents.

Fry W. Giles, the Secretary of the Association, also served as the first postmaster in 1855. He opened the first bank in May 1865 and would later write “Thirty Years In Topeka,” published in 1886. Other association members included Daniel H. Horne, who would serve as a Captain in the 2nd Kansas State Militia; M.C. Dickey, who became a prominent businessman and the United States government agent to the Kansas Indians during the territorial period and strove to make Kansas a free state and Topeka its capital; Charles Robinson later served as the first governor after statehood in 1861-1863; Enoch Chase who built the three-story Chase House hotel, in the fall of 1856; and Loring Cleland, George Davis, and Jacob B. Chase.

The original site of the city of Topeka embraced 684 acres that sold for $1.25 per acre, as set out in the Pre-exemption Act of 1841.

Many settlers who found their way to Kansas staked their claims to farm, spread the Word of God, and started businesses. By the spring of 1855, Topeka consisted of six houses made of logs or shakes plus several sod houses. Land was donated to Mr. J.T. Jones to establish a “store.” Mr. E.C.K. Garvey published the first copy of the Kansas Freeman on July 4, 1855. Miss Sarah C. Harlan was engaged to teach on September 1, 1855. The first brick school was erected in the summer of 1857 on Harrison near 5th Street. In January 1856, Mr. Walter Oakley was offered land to build a three-story hotel on the northeast corner of Kansas Avenue and 5th Street named “Topeka House.” In the fall of 1856, John Ritchie began constructing the Ritchie Block at 6th Street and Kansas Avenue. It was to become the first home of the Kansas State executive offices and the state senate. Ritchie’s home at 1116 Madison would play an important role in his activities with the Underground Railroad.

The city’s progress was impeded to some extent by the “border ruffians” troubles, Indian uprisings, and protracted seasons of drought. However, under the leadership of Holliday, the citizens soon made Topeka the largest and fastest-growing town in Shawnee County. Topeka was incorporated in 1857 and became the Shawnee County seat on October 4, 1858, after an election where it beat out the pro-slave town of Tecumseh. When Kansas was admitted into the Union on January 29, 1861, Topeka became the State Capitol.

The first bridge across the Kansas River was completed in May of 1857 but was lost in flooding in July of the same year.

“We turned a sharp angle through the magnificently fertile and admirably timbered bottom of the Kaw or Kansas to the Topeka ferry, which we reached a little after sundown, but were delayed by a great contractor’s train which had been all day crossing, and was likely to be a good part of the morrow so that we did not go across and into Topeka till nearly dark. … Along the north bank of the river a party of half-breeds have a reserve a mile wide by twenty miles long, and I give the good-for-nothing rascals credit for admirable judgment in selecting their land. There is probably not an acre of their tract that could not be made to produce one hundred bushels of shelled corn by applying less labor than would be required to produce thirty bushels on the average in New York or New England.”

— Southbound pioneer from Fort Leavenworth on the north side of the river, 1859.

A second bridge was completed in October 1865.

The ferry remained in service into the 1870s. After the ferrying business ended, the Pappans and future generations remained in the Topeka area for years. One of these descendants was Charles Curtis, a grandson from one of the marriages. Born in 1860, Curtis spent much of his youth on the Kanza Reservation with his maternal relatives. After receiving his formal education, he practiced law in Topeka before becoming the prosecuting attorney for Topeka & Shawnee County. Curtis later served on the Kansas House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate before being elected vice-president under President Herbert Hoover from 1929 to 1933.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2023.

Also See:

Early River Commerce in Kansas

Sources:

Historic Marker Data Base

Pappan’s Ferry Charette

Visit Topeka

Washburn University