Categories & Articles:

Border Ruffian Warfare in Atchison

Border Troubles in Leavenworth

Border Troubles in Linn County

Border Troubles in Morris County

Border War & Civil War Battles

Constitutional Conventions of Kansas

Jayhawkers – Terror in the Civil War

Jayhawking in the Bleeding Kansas Struggle

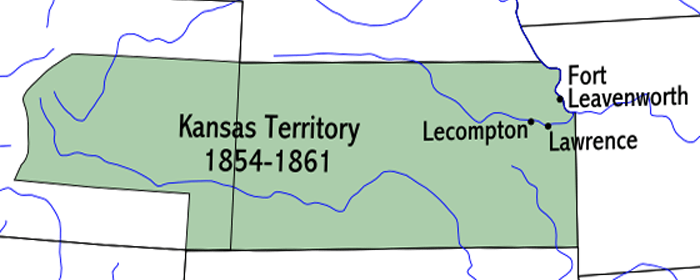

Kansas Organized as a Territory

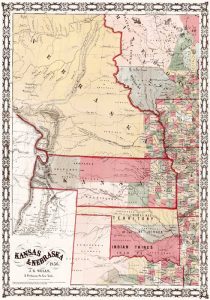

Missouri Bushwhackers – Attacks Upon Kansas

Kansas was an unorganized territory before 1854. It was home to numerous Indian tribes, including Plains tribes such as the Cheyenne and Arapaho, and less nomadic peoples such as the Kanza, Pawnee, and Osage. After the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, approximately 20 tribes east of the Mississippi River were relocated to the “Indian Territories,” which included Kansas. A few of these groups included the Shawnee, Delaware, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Cherokee, and others.

Among white settlers, soldiers were stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Fort Riley, and Walnut Creek (Great Bend) to protect travelers along the trails.

Several authorized trading posts were scattered across the Territory, including those at Elm Grove (now Gardner) and Council Grove, which served the Santa Fe Trail, and a significant post at Uniontown in western Shawnee County, which served the Potawatomi tribe and California Trail travelers. Other white settlers included the many missionaries and their families working with Native peoples at the Shawnee Mission in present-day Fairway, Kansas; Saint Mary’s Mission in present-day Shawnee County; the Catholic Osage Mission in Neosho County; and several others.

Although the tribes had been promised permanent reservations in Kansas, white settlers pressed for westward expansion. As a result, the federal government began negotiating another Indian removal in 1853. Most tribes were then removed to lands in the remaining portion of Indian Territory, which later became Oklahoma.

In May 1854, the U.S. Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and allowed the territory’s settlers to determine if they would allow slavery within their boundaries. Although the initial purpose of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was to create opportunities for a transcontinental railroad, it instead created great tension over the slavery question, sparked the Kansas-Missouri Border War, and ultimately contributed to the Civil War. Ultimately, it would be years before a transcontinental railroad would be completed.

Even before the act was passed, Missourians, hoping to make Kansas a slave state, began to pour into the territory, claiming some of the best lands ceded by the tribes, even though their treaties had not yet expired. In the meantime, organizations were formed in the Northeast to facilitate significant emigration from the Free States. As more settlers flooded into the territory, the “Kansas question” became the centerpiece of an emotionally charged national debate.

Some of the earliest settlers were pro-slavery men from Missouri, including Senator David Rice Atchison and brothers John H. and Benjamin F. Stringfellow, who established the pro-slavery town of Atchison. More pro-slavery men came to establish the city of Leavenworth. In response, the New England Emigrant Aid Company and other groups were formed to promote and support Free-State settlement. In July 1854, they founded the cities of Lawrence and Topeka as Free-State cities.

Though the vast majority of settlers were more concerned about bettering their economic situation and land rights than settling their nation’s slavery question, there were plenty of others to sway the territory their way. Within a short time, the two sides began to square off, sometimes in violent battles, and the period became known as Bleeding Kansas. Eastern newspapers gave sensationalized attention to what was happening in the territory. They fanned the flames, and the Republican Party emerged in 1854 to oppose the expansion of slavery in the territories.

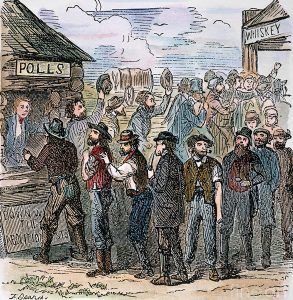

Thousands of pro-slavery men from Missouri crossed the border into Kansas to stuff the ballot boxes.

The territory’s first governor, Andrew H. Reeder, was ambivalent about slavery. Upon his arrival in 1854, he directed his energies toward land speculation and government business. However, subsequent events would force him to choose, and he sided with the Free-Staters.

By early 1855, the first territorial census revealed a population of 8,500, and Governor Reeder called for a legislative election on March 30. On that day, nearly 5,000 Missouri men, led by United States Senator David Rice Atchison and a group of prominent pro-slavery Missourians, crossed the border to “help” the legitimate electorate elect pro-slavery candidates. The result was that most of the 39 members of the Territorial Legislature were pro-slavery men. Free-Staters immediately cried foul, naming the new Kansas Territorial Legislature the “Bogus Legislature,” which led to the Topeka Movement. This unauthorized shadow government adopted its constitution and elected its legislature in late 1855. However, the Federal Government rejected the Topeka Constitution and deemed the Free-State body illegitimate and in rebellion.

Meanwhile, Governor Andrew Reeder established a capitol building at Pawnee, Kansas, near the Fort Riley military reservation. He called for the territorial legislature to convene for the first time on July 2-6, 1855. The fledgling townsite of Pawnee comprised Free-State advocates. Reeder had an apparent conflict of interest in choosing the site, as he owned stock in the town association, land in the area, and had recently built a grand log house there. The pro-slavery supporters, who comprised the vast majority of the legislators, were incensed. They believed that placing the new capital at Pawnee, some 150 miles from the Missouri border, gave the Free-Staters in the Kansas Territory an advantage. However, Governor Reeder refused to back down.

While the Legislature had no intention of remaining at Pawnee, it needed to go. The legislative members traveled to Pawnee by horseback, wagon, and carriage. During that first meeting, they organized the government, elected officers, created both houses of government, and, over Reeder’s veto, transferred the capital to the Shawnee Mission in what is now Fairway, Kansas. The Legislature then sought to remove Governor Reeder from office, which was accomplished in late July. The official reason was his land speculation in Pawnee and the Topeka area.

The Legislature recognized that the Shawnee Mission location was temporary and began establishing a new capital at Lecompton, Kansas. In the meantime, they were busy crafting over a thousand pages of laws to make Kansas a slave state. The Legislature planned to meet at their new Constitution Hall in Lecompton on October 11, 1857, but upon their arrival, they found several hundred Free-State men barring their entrance. They returned, however, eight days later, with some 200 soldiers. The legislatures then drafted the Lecompton Constitution, which included slavery, but the U.S. government would not accept it.

While the Lecompton Constitution was debated, new elections for the Territorial Legislature in 1857 gave the Free-Staters a majority in the legislature. The new legislature convened in Leavenworth, Kansas, in early 1858, and on April 3, 1858, the Leavenworth Constitution was adopted. This constitution would suffer the same fate as previous documents when the U.S. Congress refused to ratify it.

Following the defeat of the Leavenworth Constitution, the Legislature again drafted a new document, known as the Wyandotte Constitution. The convention assembled at Wyandotte (Kansas City, Kansas) on July 5, 1859. After much debate, a new constitution was submitted to the people for a vote and passed on October 4, 1859. It was then sent to the Federal Government for ratification. Following numerous long debates in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate, President James Buchanan authorized Kansas to become the 34th state of the United States on January 29, 1861. Only six days after Kansas entered the Union as a Free State, the Confederate States of America formed between seven Southern states that had seceded from the United States in the previous two months.

Though the battle for Kansas was finally over, the conflict, which had earned the territory the nickname of Bleeding Kansas for the past six years, now engulfed an entire nation.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated December 2025.

Also See:

See Sources.