Guerilla Warfare in Kansas

After the invasion of the area in March 1855 by Missourians to participate in the election of March 30, Bourbon County, Kansas, enjoyed comparative peace until July 1856. At that election, about 300 armed men at the Fort Scott precinct from Missouri cast most of the votes for Joseph C. Anderson and S. A. Williams on that day. At the time, there were probably not more than 30 legal voters in the precinct.

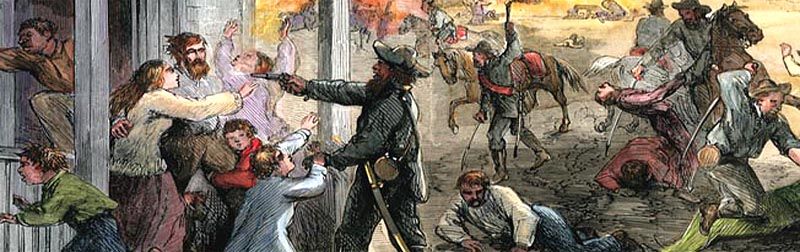

In the early spring of 1856, a party of about 30 men from South Carolina came to Bourbon County under a leader named George W. Jones, all under the auspices of the Southern Emigrant Aid Society and in furtherance of the scheme of making Kansas a Slave State. Upon their first appearance in the county, their manners were mild and conduct that of gentlemen. They visited most of the Free-State settlers, made inquiries as to where they came from, what their views were upon the pending issues of the day, how they were for arms and ammunition, and what kind of land there was in this part of the Territory; and informed them that they were looking for a good location for a colony from South Carolina. Some Free-State men were from South Carolina, such as Josiah Stewart, who had settled in Mill Creek Township in 1855. Without suspecting the final ends these pretended forerunners of a colony had in view, he gave them full information about the country itself and their own political opinions and means of defense. It thus became easy to make a complete list of the leading Free-State men, with full particulars regarding them. Then, commencing in July and continuing through the fall, those on the list were taken prisoners, taken to Fort Scott, and, in some cases, while thus held, advised by some “friend” among their captors that, if they had any regard for their safety it would be best to “skip out” and leave the Territory. In this and other ways, nearly all Free-State men were driven out during the year, and a pro-slavery man put upon each Free-State man’s claim.

Besides these operations, there was but one other important historical event that occurred during the year. That was the arrival at Fort Scott from Texas of a party of “Rangers” in August, who, in company with a like number of citizens of Fort Scott under the command of Captain William Barnes, formed themselves into a company of upward of 100, all under the command of the Texas leader, and marched north toward Osawatomie, to have “some fun.” When camped on Middle Creek in Linn County, about eight miles south of Osawatomie, they were attacked by Captains Anderson, Shore, and Cline and most ingloriously defeated.

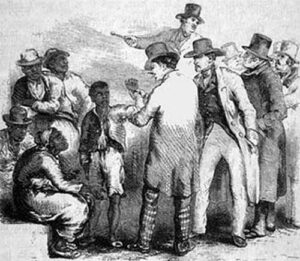

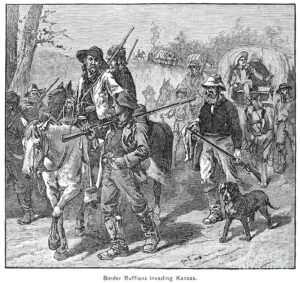

Missouri Border Ruffians

This Battle of Middle Creek, although not very important in itself, has an interesting sequel. The parties engaged in it on the pro-slavery side, who were not taken prisoners, made the best time possible – -some to Missouri, others to Fort Scott, imagining themselves closely and hotly pursued the whole distance by the “Abolitionists.”

Those who took to their heels arrived home about midnight yelling: “The Free-State men are upon us; the Free-State men are upon us; the buildings will be burned,” etc. The surprise was so sudden that resistance on the part of those who had remained at home would have proved of little account, and their only salvation was to save what they could and make the best of it. A party consisting of five or six families, with Colonel H. T. Wilson as the pilot, started for Mr. Brantley’s residence about one-half mile from the Fort. They found Mr. Brantley’s family in bed, fast asleep. Still, when awakened by the voice of Colonel Wilson asking for shelter, Mr. Brently concluded that something of unusual importance was on foot and so jumped up and opened the door when a general inpouring took place. The room was soon filled with frightened women and crying children. Confusion was no name for it. Mr. Brantley’s sons were at the Fort, but when the Free-State men were announced, they hastened home to alarm the household and to prepare for a fight. They reached home shortly after the arrival of the Colonel’s party and brought the report that everything was being destroyed and that this was their next point of attack. What was to be done? Destruction and death stared them in the face. One of the ladies suggested a season of prayer. A circle was formed, and Mr. Brantley, a very devoted Baptist, commenced to pray. We will leave them on their knees, return to the Fort, and see what became of the other people.

Mrs. Dr. Hill, who resided on the East Block, was in the act of retiring when the news reached her that the Free-State men were going to burn the buildings. Her husband and son were away at the time with the horses, and she didn’t know what to do. She called together the remaining portion of her household, informed them what was up, and told them to take care of themselves as best they could after offering prayer. She then ordered her servants to bring her carriage to the front door and, seating herself in it, ordered the negroes to draw her away to some secluded spot. In the rear of her house was a deep ravine, and an almost impassable road, even in daylight, wended its way to the bottom. Down this road, they went “a-flying” regardless of expenses, and not until they had reached the thick underbrush did they stop for further orders. After remaining here for some time, she involuntarily clasped her hands to her head and discovered that she had forgotten to take her “night cap” off in her haste. The first impression that entered her mind after the discovery was that the white cap would attract the attention of the “abolitionists,” they would shoot at it, so she took it off and put it in her pocket. She remained in the buggy all night, her servants acting as her bodyguard. The following day, the wanderers returned.

After this scare, it was thought best by those having families here to send them away. George W. Jones, who hailed from South Carolina, actively participated in this movement. He owned a large wagon with a capacity a capacity for many. He “took in” all the women and children in the country, who had no other means at their command, and started for the States, drawn by four yoke of oxen.”

In 1857, the Free-State men, driven from their homes the year before, began to return. Many new settlers entered the county this year, so with increased strength, they acquired increased confidence in maintaining their rights. As a preliminary step to regaining possession of their stolen stock and claims, they organized themselves into a “wide awake” society, in opposition to the “dark lantern lodge” of the pro-slavery men. Among the “wide awakes” leaders were J.C. Burnett, Captain Samuel Stevenson, Captain Bain, Josiah Stewart, and Benjamin Rice. This organization of “wide awakes” was accustomed to meeting at different settlers’ cabins at different times as a precaution against surprise and attack by their “dark lantern” neighbors. When everything was in readiness, the pro-slavery usurpers were notified that they must relinquish the claims they had wrongfully seized. The more significant part, now realizing that resistance on their part would undoubtedly result in defeat and possibly in bloodshed, left the appropriated claims on receipt of the notice, but other, more tenacious of these “rights” had to be driven out by force of arms. As an illustration of these difficulties was the case of Stone against Southwood. Southwood was a preacher of the Methodist Church South who had taken possession of Mr. Stone’s claim and cabin. Upon Mr. Stone’s return, he endeavored to assert his rights, but the Reverend Southwood refused to vacate. The Free-State men built Stone a cabin near the one occupied by Southwood, into which Stone moved his family to await the opening of the land office. Soon, a difficulty arose about a water well, which led to an assault by Mrs. Southwood upon Mrs. Stone. This assault led the Free-State men to order the Reverend Southwood’s family off the premises by a specific fixed time. On the day before this order was to be carried into effect, the Reverend Southwood’s pro-slavery friends, to the number of about 200 armed men, prepared to move Mr. Stone off the claim. The Free-State men collected in Mr. Stone’s cabin and awaited the attack of the Reverend Southwood’s friends. The attack was made at night but failed, the attacking party retiring to Fort Scott, threatening to return with increased numbers and to hang every Free-State man found on the premises. The Free-State men then increased their number to 60 and awaited the second threatened attack, which was made according to promise but resulted in failure as the first. As a result of the whole movement, Reverend Southwood left the premises before his time expired, and Mr. Stone was reinstated.

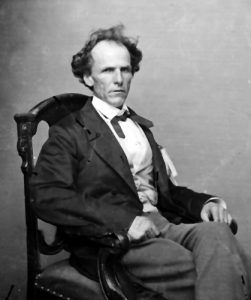

Similar difficulties were of frequent occurrence, and, indeed, the Free-State men did not have the law and the right upon their side in every instance, as a six-month abandonment of a claim worked a forfeiture of legal title under the pre-emption laws. At any rate, they were frequently arrested on various kinds of charges and harassed in every conceivable way. The District Court was presided over by Judge Joseph Williams. For a time, claim questions were referred to his court for decision. Still, the Judge, being a pro-slavery man, very generally decided in favor of the pro-slavery claimant, and the Free-State men indicted, for the most part, for imaginary offenses were either required to give excessive bail or refused bail altogether. The Free-State men were, of course, universally dissatisfied with such a state of things, and James Montgomery determined, if practicable, to bring Judge Williams to his senses. To this end, he arrested a certain pro-slavery man, kept him in custody long enough, and treated him severely enough to make him think when released that he had been in great peril and was exceedingly fortunate in being released at all, incidentally mentioning in his hearing his intention of marching to Fort Scott and forcibly releasing the prisoners held and refused bail. Montgomery’s pro-slavery prisoner, upon being set at liberty, immediately set out for Fort Scott and lost no time in informing Judge Williams of Montgomery’s program; after that, the Judge suddenly discovered that to refuse bail to prisoners under such circumstances was a thing unheard of in law and in itself absurd. The prisoners were at once released without bail and upon their own recognizance.

On account of the dissatisfaction of the Free-State men with the decisions of Judge Williams’ court, they organized a court of their own, calling it the “Squatters’ Court.” Dr. Gilpatrick, of Anderson County, was made Judge, and Henry Kilbourn, Sheriff. The proceedings of this court were regular and dignified, its decisions impartial and just, and rigidly executed by its most efficient Sheriff.

The proceedings of this squatter’s court were as distasteful to the pro-slavery men as were those of Judge Williams to the Free-State men. In consequence, on December 12, 1857, an expedition was organized and started under the command of Deputy United States Marshal Little of Fort Scott to capture the court. This attempt was a failure, and on the 16th of the month, Marshal Little organized a posse of about 50 men for a second attempt. As Little approached the “fort,” Captain Bain’s house, in which the “court” was sitting, he was met by an embassy from the “court,” consisting of D. B. Jackson, Major Abbott, and General Blunt. As Marshal Little was advancing, this embassy had been sent out under a flag of truce. At the close of the conversation, Marshal Little informed the embassy that if the “court” did not surrender in 30 minutes, he “would blow them all to hell.” The embassy returned to the “fort,” which the “court” promptly placed in a condition of defense by removing the chinking between the logs for port holes. Those with shotguns remained inside, while those with rifles stationed themselves near the “fort” behind trees. Major Abbott then warned Little that he would be fired upon if he advanced beyond a certain line. Little advanced, notwithstanding, received a volley from Major Abbott’s rifles and muskets. The Marshal’s men returned the volley and then wheeling beat as precipitate a retreat as possible to the distance of one-half a mile. Here, they halted and learned that four of their number had received slight flesh wounds and that B. F. Brantley’s horse had been shot through the neck. Little re-formed his line and asked all who were willing to make a second attack upon the “fort” to step aside with him. Ten men responded, and Little at their head made a second advance, with the same result as before, except this time none of his men were wounded. None of the Free-State men were wounded in either charge. Finding it impracticable to take “Fort Bain,” the Marshal led his posse back to Fort Scott. On the following day, as Marshal Little was approaching “Fort Bain,” with forces increased to about 150 men, he was informed by William Hinton “that his birds had flown.” Upon reaching the fort, he found this to be true, the court having retired during the night to the Baptist Church at Danford’s Mill. Here their numbers were increased to about 300. On the following Sunday, they returned to “Fort Bain” and held a “jollification” over the victory of the previous Tuesday. They then returned to the Baptist Church, disbanded, and went to their homes.

Prominent among the members of this “Squatter’s Court” were Captain Bain, Colonel Phillips, P. B. Plumb, General James Lane, and Major Abbott, who was a military commander. One of Marshal Little’s posse, James Rhoades, who was at the time engineer at Ed Jones sawmill, after returning to Fort Scott, started back to the mill up the Marmaton. On the road, he met a Free-State man, Mr. Weaver, with whom he engaged in a controversy. Weaver was unarmed, Rhoades had a gun he had in some way obtained possession of, which belonged to a Free-State man in Linn County, and besides being armed, he was under the influence of intoxicants. He attempted to shoot Weaver, but Weaver seized the gun, wrenched it from his grasp, and shot him through the head, killing him instantly. He was buried on the 20th, with Masonic ceremonies. Weaver retained possession of the gun and thereby came near getting into serious difficulty. It had an individuality and was well known to many Free-State men of Linn County. When some of them discovered it in Weaver’s possession, he was at once adjudged a pro-slavery man and had to prove himself innocent before his safety was re-assured.

About this time began what may be called the Denton difficulty. In the year 1856, a pro-slavery man named Hardwicke settled on the Little Osage River, and later in the same year, Isaac and James Denton, father, and son, and also pro-slavery men, came to Bourbon County from the South. Hardwicke permitted James Denton to settle on his claim that he should look up a claim for himself in the spring. When the time arrived for Denton to vacate the claim, he refused and referred his case to the “Squatter Court,” which sustained him. Hardwicke’s cabin was fired into, and he and his family were forced to leave the claim, but he lurked around the country for some months. About the last of March 1858, Isaac Denton and Hedrick were shot and killed. Davis’ house was fired into, and he was wounded in the hand. Hardwicke and some friends were suspected of the crime and fled the country. He was arrested in Missouri, placed in irons, and delivered to John Denton, another son of Isaac’s, to be brought to Kansas for trial. However, on the way, Denton shot Hardwicke dead. In his turn, Denton was shot and killed on October 25, 1860, at the State Line Grocery near Barnesville, by William Marchbanks in retaliation for the killing of Hardwicke.

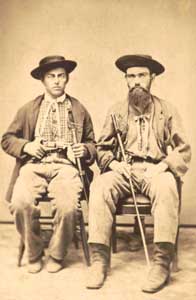

Toward the close of the year 1857, Montgomery’s band, on account of their operations on the Little Osage River, became known as the “Osages,” and the pro-slavery element as the “Pro-slaveries.” During this time, the people of Fort Scott were constantly subject to alarms by reports that the “Osages” were coming to attack the place. The Fort Scott people were composed of three classes of persons — Free-State, pro-slavery, and Border Ruffians of the worst class. Among the latter were George W. Clarke, W. B. Brockett, and the Hamiltons. Against these men, the “Osages” entertained an undying hatred, and it was because they were harbored in the city against the wishes of the Free-State and other peace-loving citizens that these annoyances and alarms were of such frequent occurrence. The Free-State men in the city did most of the guard duty and, from the peculiarity of their position, were almost constantly between two fires, or at least they had to serve as a kind of bulwark over which the “Osages” from without had to fire, or through which they had to break, to reach the Border Ruffians within.

Because of these constant alarms, a public meeting was held in Fort Scott on Sunday, December 13. Governor E. Ransom was Chairman, and J. Kennedy Williams was secretary. A committee on resolutions was appointed, consisting of Charles P. Bullock, H. T. Wilson, George W. Clarke, D. F. Greenwood, Dr. Hill, S. A. Williams, J. W. Head, John H. Little, J. Cummings, William Gallaher, Mr. Harlan, and B. F. Brantley. Governor Ransom was afterward added to the committee. At an adjourned meeting held in the afternoon, the following resolutions were reported and adopted:

Resolved, That the Sheriff and Deputy Marshal be requested to make affidavits to the facts touching the matter now under consideration and that the same be conveyed by express, accompanied by a communication to the Governor of the Territory for military aid.

Resolved, That a committee be appointed, consisting of five persons, to be denominated a ‘Committee of Vigilance,’ under whose authority and directions a military organization shall be had, to aid when necessary the civil authorities in the execution of warrants, and any other legal process, and in the due execution of the laws. It shall be the further duty of the committee to organize a night patrol for the security of our town and its citizens and their property.”

The Vigilance Committee appointed consisted of H. T. Wilson, B. Little, T. B. Arnett, George A. Crawford, and J. W. Head.

The following resolution, offered by George W. Clarke, was also adopted:

Resolved, That we recommend to the good citizens of the Territory to abstain from all retaliatory acts, and not to allow themselves to be drawn into illegal combinations or conduct by the acts of lawless men, but in all cases to maintain their rights under and by the laws of the land.”

The following communication accompanied the affidavit of the Sheriff:

“TO HIS EXCELLENCY F. P. STANTON, ACTING GOVERNOR OF KANSAS TERRITORY:

Sir: As Sheriff of Bourbon County, I feel it my duty to report to you that in consequence of an organized and armed resistance to the civil authorities by a body of armed men in this county aided and assisted by men equally lawless, I am unable to serve processes, make arrests, or otherwise perform my official duties; and I have the honor to ask that you have a body of United States troops sent to this point to aid me in enforcing the laws, and to give quiet to the disturbed state of things in this region. Herewith, I send my affidavit and the concurrent statement of Marshal Little.

JOHN S. CUMMINGS

Sheriff of Bourbon County.”

In response to this appeal, Secretary Stanton sent Companies E and F, First United States Cavalry, to Fort Scott, under the command of Captain Sturgis, arriving there on December 21. Their presence had the effect of restoring and maintaining quiet for several weeks. But on January 10, the troops were removed to Fort Leavenworth, and it was not long before the old troubles broke out afresh and guard duty was resumed. At that time, “Old Ganter,” as he was called, a German, was living on Mill Creek on a claim that he had bought in that part of the county. One night in February 1858, he came into Fort Scott and reported the enemy in his neighborhood, saying, he “vish der tam Abolitionists get frostbite mit der feet!” “Old Ganter” was somewhat of a character. He owned a slave whom he took good care of and obliged his wife to do all the heavy work. At one time, he was asked by Ed Jones if he thought it was right to drive the Free-State men off their claims as was then being done by pro-slavery men. His reply was, “Oh, vell! By Tam, der vill pe so many less to vote.” But when his time came to be driven out by the Free-State men, with characteristic inconsistency, he sought the protection of the very men of whose expulsion he had previously so emphatically approved. Ganter was afterward shot and killed by bushwhackers during the war.

When the forerunners, under George W. Jones of the South Carolina “colony,” were making their selection of claims, Josiah Stewart was advised by Jones as a “friend” to leave the Territory. Mr. Stewart acted on this advice. In 1857, he returned and took possession of his claim. In June 1860, Nathaniel Boylston returned from Texas to Kansas through Missouri. In passing through Fort Scott, some of his pro-slavery friends told him they knew of a reasonable claim they wanted to be occupied by a good pro-slavery man, and acting on the advice of a lawyer, Boylston moved onto the claim then belonging to and occupied by Mr. Stewart. The next morning, which was Sunday, Mr. S. heard someone chopping in the timber and, with one of his boys, went out to learn who it was and why. Upon approaching Mr. B., whom he did not know, he inquired of him why he was there and what he proposed to do. Mr. B. replied, “You will see in time. I propose to pre-empt this claim.” Mr. Stewart thereupon sent his son back to the house after a shotgun and revolver and, upon their arrival, went down to Mr. Boylston, who had his ox team and wagon and family with him, and some other man also for a witness to the fact of his having made his “improvement” on the claim. As Mr. Stewart came near the party and demanded of Mr. B. what he meant by attempting to pre-empt a claim already taken by himself, Mr. Boylston stepped from the opposite side to the rear of the wagon, brought his gun to his shoulder, and attempted to fire on Mr. Stewart; but the gun failed to go off. Stewart then raised his gun and fired upon Boylston, wounding him so that he died in about thirty days. Stewart gave himself up to await the result of the shooting. Upon the preliminary trial, the doctors testified that the wounds were not necessarily mortal. In the following fall, the grand jury failed to find an indictment against Mr. Stewart, and he was therefore never brought to trial. Mrs. Boylston contested Mr. Stewart’s claim but did not succeed in securing it.

On the night of February 10, 1858, scouts reported that the “Osages” were coming to the city and were certain there was no mistake about it. James Montgomery had been appealed to for assistance by a Mr. Johnson, who had suffered from the Border Ruffians of the city. He at once set out at the head of about 40 men to execute writs which had been procured against the offenders. He was met by a deputation of citizens on the outskirts of the town. Of this deputation, he demanded the persons for whom writs were held and received the reply that they should be surrendered upon the condition of being tried in Fort Scott but that otherwise, they would not be surrendered without a fight. Montgomery promptly decided to fight and put his command in motion for the town, preceded by the more rapid movements of the deputation among the members of which were Judge Williams and George A. Crawford. All the leading pro-slavery men suddenly discovered that important business interests in Missouri demanded their immediate attention, and when Montgomery arrived, the birds he sought were flown. The hospitalities of the city were extended to and accepted by the “Osages,” after which they quietly took their departure.

On the 15th, the runaways returned, and a serious difficulty arose at the Fort Scott Hotel on account of an attack by W. B. Brockett on Charles Dimon. Mr. Campbell, the proprietor of the hotel, was, however, equal to the emergency and, by his determined bravery, prevented bloodshed. On this same day, two companies of the First United States Cavalry were ordered to Fort Scott to report to Judge Williams or Deputy Marshal John H. Little; they arrived on the 26th, under the command of Captain George T. Anderson and Lieutenant Ned. Ingraham. Montgomery always desired to avoid a conflict with United States troops. Now, as they defended Fort Scott, he operated against the pro-slavery men in the country, with the object of driving them into the city. Many families, some say as many as 300, were thus broken up and ruined. Captain Anderson could afford them no security at their isolated homes, and the only recourse was to flock to the city, which they did. During these raids, much property and many horses were stolen. John Brown had a fine horse, which belonged to Mr. Poyner, and Montgomery had one belonging to J. J. Farley, which he offered, some time afterward, to permit Judge Wright to ride home to its owner, but on account of the horse being “too wild,” the Judge declined. During these raids, on February 28, a party of JamesMontgomery’s men, under the command of Reverend John E. Stewart, alias Levi W. Plumb, approached the house of Van Zumalt, a pro-slavery man living on the Little Osage, and in attempting to enter it shot and badly wounded him. He, however, recovered and left the Territory.

After the killing of Denton and Hedrick, Travis was arrested and tried for complicity in the murder. He was a harmless old man, about sixty years of age, and without marked political proclivities. The “squatter court” before which he was tried found him “not guilty.” On his way home, he stopped at Wasson’s, where, on April 1, he was shot and killed, some say by James Denton and others of Montgomery’s men.

On April 21, James Montgomery, with a small party of his men, was in the Marmaton Valley. Word was brought to Captain Anderson that a party of Osages were up the valley robbing and plundering. Captain Anderson immediately started in pursuit. On his way, he passed Jones’ sawmill, where a meeting of Free-State men was being presided over by John Hamilton. Anderson invited Hamilton to accompany him in pursuit of Montgomery, but he was “too busy” just at that time to leave. Anderson soon came in sight of Montgomery, who, upon discovering the presence of United States troops, retreated at full speed up Paint Creek, closely pursued. Arriving at a narrow defile, Montgomery dismounted his men and assumed the defensive. Captain Anderson’s troops were fired upon as they approached; one man was mortally wounded, Captain Anderson’s horse was killed, and the troops were defeated. An armistice followed to remove the Captain from under his fallen horse, and the “Osages” beat a timely retreat, having but one of their number slightly wounded. The wounded soldier, Alvin Satterwaite, a young man of good family and exemplary habits, died on the 23rd and was buried on the 24th with military honors.

It is impossible to imagine, much less to appreciate and describe, the bitterness of feeling that existed in the hearts of the two classes of the people that then inhabited the Territory against each other. Insult and wrong provoke retaliation, and the retaliators seldom cease when they have merely dealt out justice. Revenge continues to spur them on, and it is natural to desire to put the enemy hors du combat, so that he shall no longer be dangerous or a disturber of the peace. It was in some such spirit as this that a portion of Montgomery’s men, calling themselves “the committee of safety,” met the next day after the encounter with the troops and passed the following resolutions, believing as they did that the pro-slavery residents of Fort Scott had instigated the attack upon them by the troops.

“WHEREAS, A body of Government soldiers and border ruffians did, on the 21st inst. fire upon some Free-State citizens, who were peacefully and inoffensively traveling on the common highway and being incited to commit said outrageous and unlawful act by other ruffians living in Fort Scott;

Resolved,

1. That Judge Joseph Williams, the corrupt tool of slavocracy, be required to leave this Territory in six days; after that period, he remains at the peril of his life.

2. That Dr. Blake Little, J. C. Sims, and W. T. Campbell, the traitors who were elected by fraud and corruption to the bogus Legislature, be required to leave within six days–an infraction of this order at their peril.

3. That H. T. Wilson, G. P. Hamilton, and D. F. Greenwood, the infamous swindlers of the Lecompton Convention who forged an infamous constitution, be hung to death if they are caught in this Territory ten days from date.

4. That E. Ransom and G. W. Clarke, the holders of the two “wings” of the pretended National Democracy and the corrupt fuglemen of a corrupt President, have six days to leave this Territory under penalty of death.

5. That J. H. Little, James Jones, Brockett, B. McDonald, A. Campbell, Harlan, and the ruffians who accompanied the soldiers to assist and witness the massacre of Free-State citizens be sentenced to death.

6. That Kennedy Williams and D. Sullivan, who stole by legal forms horses of Free-State citizens, be sentenced to whipping and branding and then be driven from the Territory.

7. That after the departure of the Judge and Marshal, no other official officers shall be allowed to administer the law but those elected under the Free-State constitution.

8. That Judge Griffith, Major Montgomery, and Captain Hamilton be directed to carry out the orders of this meeting.

9. That Captain Anderson shall be hanged to the highest tree in Bourbon County, and every soldier put to death wherever he may be found.

10. That a copy of this notice be served on the people of Fort Scott.”

No effort seems to have been made to carry out these resolutions.

As early as March of this year, a feud developed itself in the Fort Scott Town Company. George W. Clarke was continually concocting some scheme to its injury, and on several occasions in Trustee meetings, an angry debate occurred in which George W. Clarke and George A. Crawford were the principal opposing disputants. On April 27, the feud came to a head. Dr. G. P. Hamilton and Brockett were notified by letter that George A. Crawford, Charley Dimon, and William Gallaher were to leave town within twenty-four hours, under penalty of being shot on sight.

It was now plain that Crawford & Co. or Hamilton & Co. must go. Crawford & Co. decided to stay and let the consequences be what they might. It was not long before the new state of affairs was generally understood, and a force of about twenty-five well-armed men collected to prevent the execution of the Brockett-Hamilton program. On account of the killing of young Satterwaite the week previous, it was feared the soldiers would take sides with Hamilton’s crowd, but investigation proved that only three had been induced to do so. J. H. Little and B. F. Brantley arrayed themselves on the side of Mr. Crawford, as did Captain Anderson and all of his soldiers except these three. The next morning, when they were found to be missing, a Sergeant with a guard was detailed to find them. The Sergeant proceeded to the Western Hotel, where he found Brockett and demanded of him the deserters. Brockett at first flatly refused to surrender them, but the Sergeant, who with his men was well armed, told Brockett he should have the deserters, even if he had to tear down the hotel to get them. Brockett yielded, the men were taken to camp, given their breakfast, and ordered by their comrades to leave town within one hour, under penalty of death. This order they promptly obeyed. The original parties to the feud remained mutually besieged until the next day, when Brockett, Hamilton, and most of the other border ruffians left Fort Scott for good and were not again heard of there until after the Marais des Cygnes massacre, in which they played the leading part.

The next event of importance was the arrival of troops under the command of Major General Sedgwick. This was May 6, and the troops consisted of one company of dragoons, one of heavy artillery, and a section of T. W. Sherman’s battery. On the 17th, all the troops, except the heavy artillery and battery, left for Fort Leavenworth, those remaining in command of Lieutenant Shinn. Soon, reports of the Marais des Cygnes Massacre were circulated throughout the country and of retaliatory robberies by James Montgomery’s men. All was excitement and false alarms for a number of days until, on May 29, Deputy U.S. Marshal Samuel Walker of Douglas County reached Raysville on his way to Fort Scott with writs for the arrest of Montgomery and others who of his men. He had been sent down by Governor Denver, who feared that bloodshed would result from the terrible state of excitement in Southeastern Kansas and who thought it could be prevented by the arrest of a few of the Free-State leaders. Governor James Denver had offered Marshal Walker all the troops he might need for the execution of the writs. However, the Marshal knew that Montgomery would not arrest him if he went alone and that if he went with a body of troops, Montgomery could not be found. He reached Raysville accompanied only by Major Williams. Upon his arrival there, he assembled about 200 men whom Montgomery was addressing in favor of going to and burning Fort Scott. Mr. Oakly, who was the only one in the crowd who knew the Marshal, asked him why he was there, to which he replied, “To arrest Montgomery.” Mr. Oakly advised him not to attempt it, as it could not be done. Montgomery, in his address, told his friends that a Deputy U.S. Marshal was coming down to arrest him, that the authorities would arrest Free-State men, but that they would not arrest pro-slavery men and advised the expedition to Fort Scott, which finally was the decision of the meeting. After the speaking concluded, Marshal Walker arose to address the meeting. He informed them that he was a U.S. Marshal and that if they would get out warrants for Clarke and others who were believed to have been participants in the Marais des Cygnes Massacre and furnish him with a posse, he would go to Fort Scott and arrest them. The reply to this proposition was that the Judges would not issue the warrants. The Marshal then told them to get warrants from the Justice of the Peace and that, although he, as a U.S. Marshal, had no right to serve a writ issued by a Justice of the Peace, in this case, he would do it. So armed with his writs for the arrest of George W. Clarke and others and escorted by a posse of seventy-five mounted men with Montgomery in command, the Marshal entered Fort Scott on Sunday morning, May 30. Among the first in Fort Scott to discover the Marshal’s presence was George W. Clarke. He seized his Sharpe’s rifle, ran in his shirt sleeves, and with face exceedingly pale to the hotel and gave the alarm, and then ran to his house. The Marshal soon arrested a few that he wanted and proceeded to Clarke’s house. Clarke closed his house and refused to surrender. Montgomery drew his men up in line in front of the house; Clarke’s friends, to the number of 300, quickly assembled and drew themselves up in line on the sidewalk in front of Montgomery, and not ten feet distant, every revolver and rifle on both sides on the cock. The Marshal seized a tongue belonging to a Government wagon. He was on the point of breaking down the door when Clarke put his head out of an upper window and said that if anyone would assure him that Marshal Walker was in command of the posse, he would surrender. Mr. Oakly assured him of that fact, and in a moment, Clarke opened the door and came out, his wife on one arm and daughter on the other and a carbine in his hand. He asked to see the Marshal’s writ, which the Marshal refused to show, knowing that Clarke would refuse to surrender to him on such authority. Walker drew his pistol on Clarke, told Major Williams to hold his watch and count two minutes, and then told Clarke that if, during the two minutes, he did not surrender, he should fire upon him, whereupon Clarke dropped his carbine and gave up.

Immediately upon Clarke’s surrender, Captain Campbell, the Deputy United States Marshal of Fort Scott, came forward with a warrant for the arrest of Montgomery and said to Marshal Walker, “Montgomery is in command of your posse; here is a warrant for him, now arrest him!” Walker replied, “Arrest him yourself; if I had a warrant for him, I would arrest him.”

As soon as Montgomery heard Campbell speak, he ordered his men to “shoulder arms,” “about-face,” and “double quick for their horses,” leaving Marshal Walker and Major Williams alone with their prisoners. Matters now became pretty warm for the Marshal. He was in a tight place, in a “bad fix,” and in order to get out of it, he persuaded Marshal Campbell to furnish him with a horse that he might pursue and arrest Montgomery. Upon overtaking Montgomery, he induced him to surrender. He took him back to Fort Scott, where all the people turned out to see the unusual sight of Montgomery as a prisoner.

Marshal Walker then turned Clarke and his other prisoners over to Captain Lyon, who was stationed there and was present when the arrest was made, on condition that Captain Lyon should send them the next day to Lecompton for trial. He started for Lecompton with his prisoner, James Montgomery. The next day, upon arriving at Raysville, he was overtaken by a courier from Captain Lyon, bearing a dispatch stating that he had just released Clarke and the other prisoners on a writ of habeas corpus. This news vexed Marshal Walker so much that he promptly released Montgomery and told him “to stay and fight it out,” and when he was through to report to Lecompton, all of which Montgomery promised to do.

Upon the authority of Captain Lyon, it may be stated that had not Clarke surrendered, and had he been shot by Marshal Walker, as he undoubtedly would have been, more than 100 bullets would have immediately riddled Walker himself.

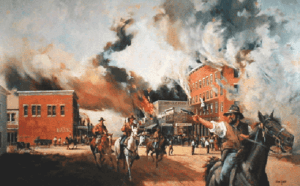

On the morning of June 7, an attempt was made by some of Montgomery’s men to burn the Western Hotel, Fort Scott, by piling a quantity of hay against it and igniting it, and a number of shots were fired into town from the southwest. No one was hurt, and the fire was extinguished before any harm was done. Captain Nathaniel Lyon was stationed in the city on the 10th for the purpose of protecting the place. On the 13th, Governor Denver arrived, and on the 14th, a public meeting was held with a view of arriving at a basis of peace. Governors Denver, Robinson, and Ransom, Judges Wright and Griffith, and B. F. Brantley made speeches. Governor Ransom, at the request of Governor Denver, made a speech expressing his views as to the cause of the troubles and as to the course the Territorial Government should pursue. He said that Montgomery, Jennison, Brown, and their men were guilty of robbery and murder and should be brought to trial and punished. Judge Wright opposed Governor Ransom’s sentiments and plan; feelings ran high, and serious difficulty for a time was feared. But by the judicious and firm course of Governor Denver, peace was restored, and the meeting adjourned until the next day.

The adjourned meeting was held at Raysville, of which Governor Denver assumed control. He made a brief address to the assembled settlers, during which he said in substance that his purpose in visiting Southern Kansas was to assist in removing difficulties then existing, that he should treat actual settlers without regard to past differences, that he believed both parties had been to blame; that his mission was to secure peace, and as a basis for an agreement, proposed the following conditions:

- The withdrawal of the troops from Fort Scott.

- The election of new officers in Bourbon County by the citizens thereof, without regard to party lines.

- The stationing of troops along the Missouri frontier to guard against invasion from that State.

- The suspension of the execution of old writs until their legitimacy could be properly authenticated.

- The abandonment of the field by Montgomery and his men and all other bodies of armed men on both sides.

As soon as the Governor had concluded his address, numerous calls were made for Montgomery. His appearance had the effect of reducing the assembly to breathless silence. The most intense interest was manifested in what he had to say, as he was universally recognized as the leading spirit of the party with whom the Governor was making a compromise. Montgomery said, in substance, that he accepted the terms the Governor had proposed and thanked him for the spirit of justice by which he appeared to be actuated; that justice, which for so long had been a stranger to the Free-State party, was what of all things it most desired; that he should with the sincerest pleasure, return to his home, and that when the Governor redeemed the pledges he had that day made, he would disband the three hundred men that followed his banner and his fortunes and retire to his cabin home, there to remain.

Tranquillity was thus restored, and both parties seemed to strive for some months to preserve the peace. On June 25, Captain Lyon wrote to Governor Denver that the agreement up to that time was fully observed, and on August 5, Governor Denver wrote that the troops were no longer needed at Fort Scott. But notwithstanding this quietude, the embers of turmoil were not extinguished, only temporarily smothered and liable to burst forth into flame at any moment on the least provocation. The pro-slavery men and many who were Free-State men were much dissatisfied with Governor Denver for making a compromise with Montgomery, believing with Governor Ransom that he and his “banditti” ought to be brought to punishment; and a difference of opinion developed as to what were the terms of the compromise. Montgomery’s men claimed that although it was not so stated in the treaty, yet it was the distinct understanding that no arrests should be made for any offenses committed before June 15, the day upon which the compromise was effected, that “bygones should be bygones,” and that all would do their best to preserve the peace. The pro-slavery party claimed, on the other hand, that the compromise did not mean that there should be entire immunity from punishment for all crimes committed before June 15, but only that private individuals should refrain from inflicting punishment according to their code and pleasure; and that it was an article of that compromise that all such offenses should be referred to the Grand Juries of the proper counties; that that compromise only pledged immunity from punishment for political offenses; that it could not and did not condone crimes against the law. Thus, the Denver compromise left room for vast differences of opinion, disputes, and difficulties. What the Free-State men and Jayhawkers called a “bygone” the pro-slavery men and sometimes officers of the law did not call a “bygone.” What the former called a “political offense,” the latter called a “crime against the law.”

In the meantime, however, George W. Clarke, who had been so long in the land office at Fort Scott, who was one of the worst, if not the worst, of the evil geniuses of the border, and for whom there are even now few, if any, to speak well, had been got rid of, to the great joy of all the citizens. In August, the President had appointed him to Purser in the Navy, and he left Fort Scott under an escort, which conducted him safely into Southwestern Missouri.

The following extract from a letter written by a pro-slavery man on November 10, 1858, shows the general estimate in which George W. Clarke was held:

I suppose the Governor (Denver) forgot to name George W. Clarke, a pet in the land office at Fort Scott, who was the real cause of all the troubles in that region and that a company of Dragoons had to be stationed there to protect him from the merited vengeance of an outraged people. He forgot to say that the Government “pet” had, in the summer of 1856, plundered, robbed, and burned out of house and home nearly every Free-state family in Linn County while his hands were steeped in innocent blood, and the light of burning buildings marked his course. This being the case, was it any wonder that the country arose in a flame of indignation and clamored for revenge against the soulless wretch placed in their midst and rewarded for his brutality?

I am no friend to Montgomery nor to those who sustain him, for he caused many civil and unoffending families to abandon their homes. Had he, after having raised his forces, marched to Fort Scott, demanded the surrender of the murderer Clarke,* and then strung him up to the nearest tree and gone home to his business, he would have deserved the gratitude of his country. But he showed himself a desperado and a plunderer, and his gang played a stronger game for their pockets than they did for the safety and security of the people.

It is now conceded that Clarke was innocent of the murder of Barber–time has shown that he, in common with many others, was accused falsely in those troublous times.”

It is not easy to state with certainty which party first broke the truce, but on November 16, Ben Rice was arrested on a number of indictments by Charles Bull, Sheriff of Bourbon County, and on the same day or about the same time, the houses of Poyner and Lemons, a short distance north of Fort Scott, were robbed by some of Montgomery’s men. One of the indictments against Rice was for the murder of Travis, who had been shot on February 28. Montgomery regarded this as a violation of the treaty of June 15, looking upon the act as a political offense or “bygone,” while the other side regarded it as a crime against the law. Then followed a couple of weeks of horse-stealing, robbing, and threats of personal violence, which led to a second meeting at Raysville, held December 1, with the view of restoring peace again. At this meeting were W. R. Griffith, President, J. C. Burnett Reverend M. Brockman, Vice President, and J. E. Jones, Secretary. The compromise of June 15 was discussed, and a new set of resolutions was reported and adopted. A resolution that all offenses committed prior to June 15 last be referred to the Grand Juries of the proper counties was lost by a vote of 64 to 109. A motion was then made by Reverend M. Brockman, but subsequently withdrawn, “that we now go to Fort Scott and release Benjamin Rice.” At this meeting, Montgomery made the statement that by finding indictments against Rice and others, the compromise had been broken. This brought out a letter from Judge Wright denying the truth of the statement but saying that if all the pro-slavery men were of the stamp of Dr. Little and son, neither Montgomery nor Brown would then be in the field “driven almost, if not entirely, to be maniacs.” Ex-Governor Denver also wrote a letter dated December 19, denying that Montgomery’s was the true interpretation of the treaty of June 15. He wrote: “In that agreement, it was never intended to compromise the laws of the Territory by debarring the Grand Juries from the proper discharge of their duty. The agreement was substantially this: That for past offenses, no arrests should be made, except upon indictment found by the Grand Juries.”

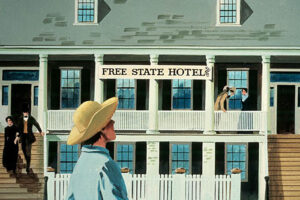

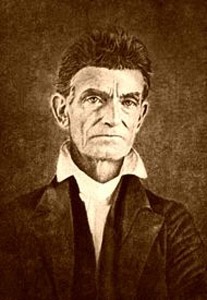

But on this question, it was impossible for the two parties to agree, and Montgomery fully determined upon the release of Rice. Accordingly, on December 15, he organized a rescue party of nearly 100 men, Old John Brown being one of the parties. John Brown, however, did not enter Fort Scott with Montgomery for the reason that the two differed as to what should be done with the city upon entering it. Brown was in favor of its complete destruction, or, as Montgomery afterward said to parties still living: “If Brown had been in command of the party instead of myself, not one stone of Fort Scott would have been left upon another.” Montgomery’s main object was to release Rice. He, therefore, proceeded with his men without Brown, leaving him at what was called the “Wimset farm,” about three miles from Fort Scott up the Marmaton and entering the city about daylight. Upon approaching the house in which Rice was held prisoner, one of the large double houses built by the Government, then called the “Free-State Hotel,” and kept by Colonel William T. Campbell, now occupied as a residence by Judge Margrave, Montgomery divided his command into three divisions of twenty each. One of these divisions passed quietly around to the right of the hotel, another as quietly to the left, while the third division entered the house by the front door, which had been left unlocked for the convenience of George A. Crawford, who, upon Little’s invitation, slept with him that night in the store. Thus, the hotel fell easy prey to the mob. This third division went upstairs into the third story, or attic, where they found Rice chained to the floor. A chopping axe was soon brought up, and with it, the chain that was around Rice’s leg was severed, and thus, the prisoner was released.

While this was going on, a tragedy was being enacted just across the alley from the hotel. Here was the building or store in which Little and George A. Crawford had passed the night. The front end of this store faces southwest, and the side is next to the alley toward the southeast. At both the front and side is a door over which there is a transom. In this store, Little and George A. Crawford were sleeping. The noise made by the rescuing party awoke them, and Little, opening the front door, fired upon the party with his shotgun, which he had used the day before in hunting ducks. The duck shot with which the gun was loaded lodged in the heavy overcoat worn by J. H. Kagi, doing but little injury to Mr. Kagi. Immediately after firing his gun, Little closed the front door and locked it, went to the side door, placed a dry goods box against it, and mounted the box to look out through the transom to see what was going on. The transom window being covered with dust, he proceeded to clean it with a handkerchief so that he might see out. The movement of the handkerchief was noticed by Montgomery’s men in the alley, one of whom raised his Sharpe’s rifle and fired at the handkerchief, not being able to see Little but hitting him almost precisely in the center of the forehead, from which shot he of course instantly fell to the floor, and expired in about an hour. The cannon was immediately brought to bear upon the store, and a demand was made for its surrender. This demand was not complied with. But an entrance to the store was effected through the back door, which Dr. Blake Little opened to admit Miss Louisa Conway. Montgomery’s men then robbed the store of about $7,000 worth of goods, consisting mostly of dry goods, but quite a number of ladies’ saddles were taken.

Alexander McDonald, then living in the house now owned by General C. W. Blair, opened his door and stepped out upon the porch. Upon refusing to surrender, he was promptly fired upon by C. R. Jennison, the bullet passing through the door. Mr. McDonald immediately retreated into the house unharmed. From twelve to fifteen of the citizens of Fort Scott were made prisoners, among them Colonel and Mrs. H. T. Wilson. It was the design of Montgomery’s men to burn Colonel Wilson’s store, but Montgomery, discovering, as he thought in Mrs. Wilson, a resemblance to Dr. Hogan, who had at a certain time befriended him, and upon learning from her that she and the doctor were brother and sister, gave the order that the store should not be burned, upon the condition, however, that the Colonel should furnish breakfast for fifty of his men. The Colonel ordered the breakfast at the “Western,” or pro-slavery” hotel, but not a mouthful of it was tasted for fear of poison.

Little was buried the next day in the west part of town and subsequently removed to Evergreen Cemetery. The following resolution, passed with others on the day of his burial, shows the estimation in which he was held by his brother Masons: “That our brother living, was an ornament to society, a worthy representative of the genial spirit and kindly virtues of our order, and in every sense a noble, generous, brave and upright man.”

After the occurrence of this affair, the citizens of Fort Scott made an application to Governor Medary for protection. The Governor, having no troops to send, advised the organization of the home militia to act as a Marshal’s posse in arresting criminals and enforcing the law. The first company was organized on December 24, with John Hamilton, Captain; C. F. Drake, First Lieutenant; and E. W. Finch, Second Lieutenant. Two other companies were organized. Of one of these, Alexander McDonald was Captain, A. R. Allison was First Lieutenant, and W. C. Dennison was Second Lieutenant. Of the other, J. G. Parks was Captain, and Hugh Glen and E. W. Black were Lieutenants. Daily drilling continued for some time, the ranks of the companies being readily filled by a promise of pay at the rate of $3 a day. The promise was never redeemed. Governor Medary, having made a requisition on the Government for a number of smooth bore muskets, said muskets were forwarded to Sedalia, Missouri, the end of the Pacific Railroad, in January 1858, whence they were taken to Paris, Linn County. On January 30, a party of fifty Bourbon County Militia started on a four-day trip to procure the new arms. Upon their return, preparations were at once made to make a raid in pursuit of “Jayhawkers,” and after three days’ scout all along the Little Osage River, about a dozen prisoners were brought to Fort Scott. After a needed rest of a few days, a guard started for Lawrence with the prisoners for trial, camping near Black Jack on the night of the 14th. The next morning at the Wakarusa, they were met by the news of the passage of the “Amnesty Act,” which rendered all their labor in vain. The captives were set at liberty, and about twenty of the captors continued on to visit Lawrence, where on account of their leader being named “Hamilton,” he was supposed by the citizens of that city to be Captain Charles A. Hamilton of Marais des Cygnes Massacre fame, and reception very much more earnest than kind was accorded them.

After the passage of the “Amnesty Act,” there was but little more trouble in Bourbon County on account of border feuds. Peace had apparently come to stay, and when the Fourth of July approached, the people decided to hold on that day a grand celebration, as evidence not only of their patriotism but of their desire for peace as well. The people of Fort Scott prepared and gave the dinner and a most memorable dinner it was. There were wagonloads of beef, mutton, and pork and immense quantities of bread, cake, and pie. A four-horse wagon load of ice was brought from the Marais des Cygnes for the purpose of making lemonade. Everybody participated in the ceremonies. Governor Ransom was President of the day; Judge Joseph Williams, Colonel Judson, Judge Farwell, M. E. Hudson, Thomas Helm, S. W. Campbell and Colonel Moran, Vice Presidents; Reverend Mr. Thompson, Chaplain; Mason Williams read the Declaration of Independence, and L. A. McCord was Orator of the Day. In the evening, there was a grand ball at the Free-State Hotel.

During the remainder of the year, immigration poured into the county, and material progress was visible on all sides. The principal occupation of the District Court was the punishment of horse thieves. In May 1860, the arch-horse thief of the border was brought to trial in Fort Scott. This was “Pickles,” whom everybody knew. The indictment upon which he was to be tried was for robbing Indian Seth the fall before. Some members of “Pickles'” gang came to the Little Osage River and endeavored to raise a rescue party. In order to forestall any such attempt, members of the Vigilance Committee armed themselves and poured into town to the number of nearly two hundred. Having assembled, their object changed from that of preventing a rescue by Pickles’ friends to making a rescue themselves and executing summary vengeance upon one who had committed more crimes than any other two of the border thieves. The officers of the law who had Pickles in charge were too wary and adroit to permit this program of the Vigilance Committee to be carried out. Pickles was too sharp to voluntarily place himself in their hands by pleading “not guilty,” which would have been the result of so pleading because he could not have been convicted on the evidence. He, therefore, in order to save his life, plead guilty, was immediately sentenced to one year in the penitentiary, and to pay a fine of $500, and escorted to Washington. Pickles fared much better than did Hugh Carlin, who, having given the settlers on Little Osage a great deal of trouble, was taken from the house of F. A. Monroe, and hanged by a party of mounted men belonging to the Vigilance Committee, about July 10. This was followed on November 16, 1860, by the killing of L. D. Moore by Charles R. Jennison in retaliation for the killing of Carlin. Jennison’s party consisted of about 25 picked men. Upon reaching Moore’s house, Jennison rapped on the door and demanded admittance, which was refused. Jennison immediately kicked the door down and shot Moore while he was sitting on the side of his bed. Jennison then passed into the house and took Moore by the wrist, holding it until the pulse ceased to beat when he exclaimed: “Boys, he’s dead.” Jennison and his party then went to the house of M. E. Hudson, whose wife was a relative of L. D. Moore. Mr. Hudson was away from home. Jennison informed Mrs. Hudson of what he had done and, while she was weeping, ordered her to provide breakfast for his party, which order she obeyed.

L. D. Moore settled in Kansas in 1857 on a claim near Mapleton. He was a pro-slavery man, was a member of the “anti-horse thief” or “dark lantern association,” and had taken an active part in the lynching of Guthrie and Carlin, his office having been that of hangman.

On about December 1, General Harney, in command of about 200 United States soldiers, arrived in Fort Scott for the purpose of attending the land sales, which came off on the 3rd of that month. The attendance was very large; everything passed off quietly, but only fourteen eighty-acre tracts were sold–the prices ranging from $1.25 to $5.50 per acre.

On the 8th of the month, General D. M. Frost’s brigade of Missouri militia reached and camped at the State Line, and General Frost and staff rode into Fort Scott to confer with Governor Medary and General Harney with reference to raids into Missouri from Kansas.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, October 2023.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War

Bourbon County, Kansas in the Civil War

Fort Scott Military Post – National Historic Site

Source – Cutler, William G; History of Kansas; A. T. Andreas, Chicago, IL, 1883.