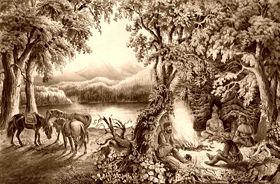

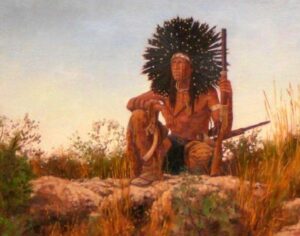

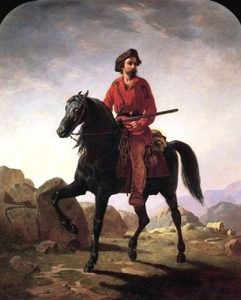

Custer’s Scouts – Sketched by Theodore R. Davis, original in Harper’s Weekly Magazine, June 1867.

During the tumultuous period between 1857 and 1878, Kansas played both a tragic and heroic role in the various Indian wars that plagued the western frontier. Like her neighboring states of Nebraska and Texas, as well as the Dakota Territories, Kansas suffered greatly from attacks by Indian raiders. Many residents lost their lives in the flames of burning homes across the settlements along the Smoky Hill River, the Republican River, the Arkansas River, the Solomon River, and other areas.

In response to the atrocities committed, Kansas sent its sons to seek vengeance. While Kansas shared similarities with other frontier states in these respects, it stood out in one area: its contribution of the Great Plains Scouts to the frontier war. In this regard, Kansas surpassed all other Western states.

Between 1860 and 1878, the major Indian campaigns were led primarily by men from Kansas. These men proved to be keen observers and adept navigators of the trails. They were skilled at diagnosing ambushes, providing wise counsel to counter the deceit of Indian diplomats, and serving as interpreters during councils. In essence, more men from Kansas excelled as high-class scouts in the Indian wars—often occupying a role that was more critical than that of the commanding officers—than individuals from any other state or territory.

Notable figures such as Sharp Grover, Billy Comstock, Charles Reynolds, Billy Dixon, Jack Stillwell, Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill Cody, William E. Mathewson, even Kit Carson, and William Bent, either honed their skills or received part of their training in plainscraft, Indian strategy, and lessons in resilience, endurance, and loyalty on the plains of Kansas. To understand this phenomenon, it’s essential to recognize that the West’s frontier history is divided into three significant periods, each marked by the advancing presence of white settlers and the growing resentment of Native Americans in response to this encroachment.

The first historic period was of the trapper and the trader. A wild, daring, irresponsible class of men they were, those forerunners of the pale face’s civilization. They little resembled heralds of civilization. More savage in dress, actions, and habits were many of them than the very Indians among whom they wandered to wrest their precarious livelihood from the wilderness. Yet they sowed the seeds from which were to spring the beginnings of the new era.

These trappers and traders demonstrated remarkable hardihood and resourcefulness, braving the risk of torture and death to filter among the wild tribes of the plains and mountains in search of beaver and other animal pelts. In this search, they penetrated to the uttermost corners of the present United States. They went in search of furs, but they acquired something more important to the nation than that — a priceless knowledge of the geography, people, and characteristics of the great unknown hinterland, which, disseminated in the East, probably had greater influence on the quick settlement of the West than any other one factor.

To this period belong men like Kit Carson, the Bent brothers and their partner, Ceran St. Vrain, “Old Bill” Williams, Jim Bridger, “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick, Jim Beckwourth, Ezekiel Williams, and others. These were but the better-known typical examples of the hundreds who were cut out of the same cloth, and who could shoot “plumb-center,” trail a moccasin track over bare rock, battle a grizzly bear with a bowie knife, and live off anything in hunger time, from their leggings to “raw buzzart,” as occurred in one traditional case.

The early settlers did not arrive as conquerors of the land; the soil held no more significance for them than it did for the Native Americans. They often formed friendships with the Indigenous people when it served their unpredictable interests, frequently marrying into their tribes, and at times participating in their tribal conflicts. In several instances, they made significant changes in the relationships between the tribes.

After the building of Bent’s Fort, the Bents and St. Vrain, with Kit Carson and Ed Curtis, traded with the Comanche and Kiowa. The Cheyenne at that time — about 1828 or 1829 — still lived north in the Black Hills of South Dakota. To increase their trade, Bent and St. Vrain built the trading post on the Canadian River in Texas, known as the Adobe Walls, from the material used in building the fort. This post was not long occupied. Trouble was stirred up among the southern Indians by the “Spanish” traders of Santa Fe, Taos, and other New Mexican towns, who were jealous of Bent and St. Vrain. Things reached such a crisis that St. Vrain, in charge of the southern post, was forced to use deception to escape.

The Kiowa and Comanche had run off his stock. He raised a white flag and invited their chiefs to a council. As soon as these chiefs entered the stockade, he closed the doors and promised them death unless the stock was returned speedily and he was given safe conduct to Bent’s Fort. General George Custer and others later used this stratagem, but this was the first time it appeared on the plains. It was effective. The mules were returned, and St. Vrain was unmolested in his northward journey.

With the Indians still refusing to trade with them, William Bent, with true Yankee cunning, looked around for a new source of business. He had dwelt among the Cheyenne and had a Cheyenne wife. He arranged a meeting with some of the Cheyenne leaders who were hunting in the Arkansas River Valley, and after a large powwow, he induced about half the tribe to move their permanent camps from the northern hunting grounds to the vicinity of the fort.

This was how the southern Cheyenne separated from the northern Cheyenne, who remained in the North. Although these bands were always considered different and distinct tribes, they were, in all essentials, the same. History records that they were intermarrying and visiting back and forth as late as 1875, when the band of Bull Hump, a northern Cheyenne, returning from a visit to the southern Cheyenne in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma), was set upon and wiped out by soldiers and buffalo hunters at the Battle of Sappa Creek, in northwestern Kansas. This provides an interesting illustration of how white men changed the habits, history, and habitat of many Indian tribes.

With the beginning of settlement in the eastern part of Kansas and Nebraska, a second historic period began. The discovery of gold in California’s mountains sparked a rush of emigrants. The slavery question caused thousands to move into Kansas with the purpose of making it a pro-slavery or a Free State. Thus, it was discovered that the “Great American Desert,” so-called, was really a fertile and productive territory.

The Indians naturally resented this intrusive behavior. Beginning in 1857, when Major General Edwin Sumner led military campaigns against the Cheyenne, the frontier was constantly at risk of raids. Young people on the frontier were taught the techniques of fighting Native Americans, the skills of navigating the woods and plains, and trained in various strategies to counter the fierce nomads of the wilderness. This was a time when many Kansas scouts received their training, preparing them for the challenging and significant adventures that would unfold during the third historic period of the Indian Wars.

In 1858, gold was discovered in Colorado, sparking a new wave of emigrants who began traveling up the Santa Fe and Platte Trails. The passage of thousands of white men with their stock and their families up these trails, frightening away the game, excited and angered the Indians. Trouble soon broke out. There were brushes with the red men on the overland trails, and then sporadic raiding began against isolated settlements. In the main, however, the tribes kept the peace until 1863, when minor depredations increased to a point where they resembled a general war, and the government, in the throes of civil war, decided it. Must do something to put an end to these troubles. There were several minor fights with the Indians, and on November 29, 1864, the Sand Creek Massacre of Chief Black Kettle’s village by Colonel John Chivington set the whole Indian country into a blaze of hatred.

The primary theater of war was in Wyoming and the Platte Valley of Nebraska during 1865 and 1866. In 1867, General Winfield Scott Hancock’s campaign in southern Kansas and present-day northern Oklahoma accomplished little, aside from giving the Native Americans renewed confidence. The following year, 1868, brought three significant defeats for the Native American tribes: Colonel G. A. Forsyth’s command repulsed Roman Nose’s band at Beecher’s Island; General George A. Custer launched a winter attack on Chief Black Kettle’s village on the Washita; and General Eugene A. Carr defeated Tall Bull’s band at Summit Springs. In each instance, the leading chief was killed.

After that, the Indians subsided until 1874, when, maddened by white buffalo hunters who ignored the Medicine Lodge peace treaty, they flamed into revolt again. For the next year, the troops were kept busy pursuing the hostiles, and the bloody battles of Adobe Walls, Palo Duro Canyon, and elsewhere, together with scores of massacres and raids, painted the frontier a gory hue.

Scarcely had this war been brought to an end in 1875, when the Sioux to the north went on the warpath. In the year that followed, Charles Reynolds was defeated on the Powder River, Crook was defeated on the Rosebud, and Ouster and all his immediate command were wiped out on the Little Bighorn. The Sioux were finally subdued, and the Northern Cheyenne were rounded up and moved to the reservation of the Southern Cheyenne in the Indian territory (Oklahoma), which precipitated Kansas’ last real Indian raid — the Dull Knife raid of 1878.

That campaign, resulting in the death of scores of Kansans in the path of the desperate Cheyenne, ended Indian troubles in this state. However, in other states, notably in Colorado during the Ute uprising, in Arizona and New Mexico during the Apache wars, and in the Dakotas during the Ghost Dance outbreak, there was plenty of bloodshed and bitter fighting before the red warriors were convinced that, whether it was right or not, they might hold the winning hand.

Ghost Dance.

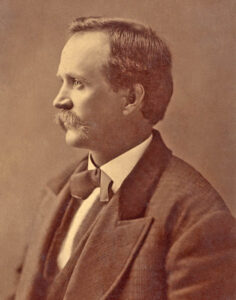

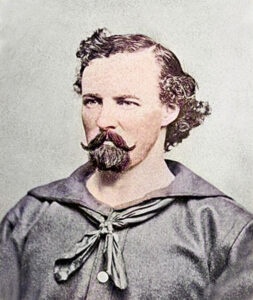

One of the bravest and most outstanding of them was Charles Reynolds. Born in Kentucky in 1842, he came to Kansas at the young age of 17 by way of an emigrant train bound for California. Indians attacked the train on the Platte, and most of the emigrants were killed, but Reynolds escaped to become a Nemesis to the race that had done that deed. After some wandering, he came to Atchison County and, at the opening of the Civil War, enlisted in and served in a Kansas regiment for three years, chiefly as a scout.

At the end of the war, he went on a trading expedition and again ran afoul of the Indians when his party was attacked on the Smoky Hill River. Reynolds’ fellow trader was killed, but he took refuge in a Wolfer’s dugout and stood the Indians off until nightfall, when he escaped and finally reached Santa Fe in safety.

During the summer of 1866, Reynolds hunted buffalo in western Kansas and eastern Colorado, where he earned such a reputation as a plainsman that he was appointed an army scout. He accompanied the troops north in 1873 and was Ouster’s chief of scouts in the Black Hills Expedition in 1874. Reynolds was the one who discovered that Rain-in-the-Face, the Sioux chief, was guilty of the murder of Doctor Honzinger, a veterinarian, and Balleran, a sutler, during the Black Hills Expedition. He also helped arrest the chief.

Reynolds was chief of scouts in the ill-fated expedition to the Little Bighorn River. He died trying to stave off the rush of the Sioux warriors who were shooting down the soldiers of Major Reno as they tried to retreat across the Little Bighorn River. He is buried, and a tablet shows where he died bravely fighting, on the field of the Little Bighorn.

Another excellent scout and daring fighter was Sharp Drover. He is said to have been a “squaw man,” having lived as a member of the Sioux tribe and married a Sioux woman. When Colonel Forsyth organized his famous expedition for the Beecher Island campaign, Drover went along as chief of scouts.

That was a fundamental distinction in that group, for most of them were veteran plainsmen in their own right. They were all Kansas men, too — trappers and hunters and ranchers and ex-soldiers, many of them former members of the Confederate Army. In this hard-bitten, efficient detachment, Drover still managed to stand out, and his commanding officer later wrote of his high opinion of and trust in him. He could speak Sioux and was also an expert in sign talk, the universal language of the plains. Moreover, he was a finished plainsman.

Primarily through his guidance, General Forsyth trailed and overtook the Cheyenne and Sioux under War Chief Roman Nose and fought the almost disastrous battle with them on Beecher’s Island. It was Drover who pointed out a huge Indian as Roman Nose himself, and Drover is reputed to have killed this Indian, although the Cheyenne later denied that this was Roman Nose. Still, Roman Nose was killed in this battle, and Drover should have known him from personal acquaintance. The writer’s opinion is that he was correct in his identification.

At the time he scouted for Forsyth, Drover was suffering from a still unhealed wound in the back, which he had received when Sioux Indians treacherously killed his friend Billy Comstock in August 1868 on the Solomon River. This occurred only a month before the Forsyth expedition. Yet, the painful hurts did not prevent him from riding, fighting, and scouting as daringly and as intelligently as at any period in his life.

Sharp Grover was killed in a shooting affray at Pond Creek Station at Fort Wallace, Kansas, in the year following this campaign. He was shot by a man named Moody in a saloon brawl. Grover was not armed, having delivered his pistols to the barkeeper, but Moody was allowed to go free as he claimed he had shot in self-defense, thinking Grover armed, when the latter, drunk, started toward him with a flow of abusive epithets.

The name of Billy Comstock has been mentioned above. He was another Kansas scout who stood high in the esteem of the officers with whom he associated. In General George Custer’s book, My Life on the Plains, he is referred to as “a host in himself” when fighting against the Indians.

Billy Comstock was born in Wisconsin but came west at an early age, preferring to live on the frontier. He was one of the original Pony Express riders at a time when Wild Bill Hickok and Buffalo Bill Cody were similarly employed.

In the winter of 1867, he got into trouble in a fight with a cheating wood contractor who had agreed to pay him a certain sum of money if he would show him where a good supply of wood for the post at Fort Wallace could be found. Comstock lived up to his part of the agreement, but the contractor failed to pay.

This man posed as an evil man and boasted of having been a member of Quantrill’s Raiders, but that made no difference to Comstock. He met his defrauder on the porch of the post trader and shot him dead. His arrest followed, and he was taken to Fort Hays, Kansas, for trial. Arraigned before a judge there, he was asked how he would plead.

“Guilty, Sir,” Comstock replied.

The astonished judge asked him if he wished to alter his plea.

“No, sir,” said Comstock, who did not know what it was to lie.

“In that case, I discharge you for want of evidence,” said the judge, who seems to have known Comstock’s late adversary.

In 1868, when the Indian war broke out, General Phil Sheridan sent for Comstock for the purpose of employing him as chief of scouts. Comstock refused to come at the summons, fearing he would be rearrested for the killing of the wood contractor. So, Sheridan, emulating Mahomet in the incident of the mountain, went to him and offered him the position.

He accepted and left his ranch, never to return to it. It was during this service that he met General George Custer. He was chief scout for that officer during the campaign, which resulted in the massacre of Lieutenant Kidder and his men, and also in the fight of Colonel Cook with the hostiles between Fort Wallace, Kansas, and Fort McPherson, Nebraska.

Comstock’s tragic death has been mentioned. He was with Grover, and they were out on a scouting expedition to see if they could discover any traces of hostiles. About 50 miles from Fort Wallace, they found the friendly village of Sioux under Turkey Leg, on the banks of the Solomon River. Grover knew these Indians well, as his wife was a member of the band.

Turkey Leg informed them that Roman Nose and his Cheyenne dog soldiers were in the vicinity. Taking the warning, Comstock and Grover started for the fort. Comstock had a beautiful ivory-handled six-shooter. A young Indian had tried to trade him out of it, but he refused. On the way to the fort, the two white men fell in with several young braves and were conversing with them in a friendly manner when two or three suddenly whipped their rifles out and fired, killing Comstock instantly and wounding Grover. The latter defended himself with a rifle, driving the Indians off. Wounded as he was, he made his way to the nearest railroad station, where he was brought to the post. General Bankhead sent out an expedition that brought in Comstock’s body and gave it a Christian burial.

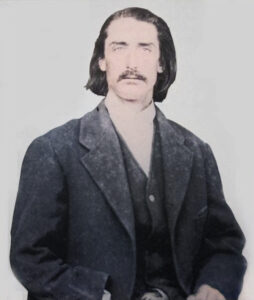

Jack Stillwell, whose real Christian name was Charles, was another member of the Forsyth Expedition who later became famous as a scout. At the time he enlisted with Forsyth at Fort Hays, he was just a boy, only 19, but already an experienced hunter and plainsman. He took part in the Beecher Island fight and, with Pierre Trudeau, was the first to volunteer to get through the Indian cordon when night fell and go for help.

The pair managed to get only a short distance when daylight came, and they hid all day in a small washout, in full view of the Cheyenne camp. Fortunately, the Cheyenne didn’t investigate the place, and when night fell again, they resumed their journey. This time, daylight caught them in an open plain, with nothing better to hide in than a buffalo wallow. The story of what followed has been disputed, but it is given for what it is worth:

Soon after, they took refuge in the wallow, and a band of Cheyenne came up and dismounted about 50 yards away. At almost the exact moment, a rattlesnake made its appearance, crawling down into the wallow toward the two men. They were in a fearful dilemma. If they killed the snake, the noise would be heard by the Indians who were almost on top of them. If they did not kill it, it would be almost sure to bite one or both of them. Stillwell unexpectedly solved the problem. He was chewing tobacco, and as the reptile approached, he expectorated a mouthful of tobacco juice all over its head and eyes. That routed the unwelcome visitor, which turned tail and crawled dejectedly away. Soon after, the Indians also left, and the men were free to continue, eventually reaching Fort Wallace with news of the fight.

After that, Stillwell’s reputation as a scout was made. He served with distinction under General Custer and was a guide for the 19th Kansas Volunteers during its winter campaign in 1868. He also served during the campaign of 1874, and made a daring ride from the Darlington agency to Fort Sill, 75 miles alone through hostile country, to bring news of the outbreak and get help. Later, he was a scout for General “Black Jack” Davidson.

At the close of the war, he acted for a time as a deputy United States marshal and later was a United States commissioner at Anadarko. He spent his last days on Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wyoming ranch.

The name of Billy Dixon is known wherever the Indian War of 1874 is recalled. He was probably the outstanding single figure of that struggle, an individual hero at the battle of Adobe Walls and the Buffalo Wallow fight, and a scout who served with distinction.

Dixon was born in West Virginia, but came west to Missouri at the age of 12 to live with an uncle. Two years later, he went “on his own” to Kansas and the plains. At Leavenworth, he obtained a job as a bullwhacker for a wagon train operating between that city and Fort Scott, Kansas. Later, he freighted between Leavenworth and Fort Collins, Colorado, and drove a wagon for the government peace commission to the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867.

From bullwhacking, he drifted into wolf hunting, and then into buffalo hunting, in which he engaged from 1870 to 1874, hunting buffalo first in western Kansas, then gradually drifting south into the Indian territory and finally the Texas panhandle. In this work, he became a wonderfully proficient rifle shot; in fact, he was one of the most expert ever seen in the Southwest.

During the summer of 1874, he was hunting in the vicinity of the old Adobe Walls location of Bent and St. Vrain, when the Indians, without warning, suddenly went on the warpath. They killed a number of hunters and made a surprise attack on the hunters’ stockade at Adobe Walls, where Dixon, with 25 other men and a woman, the wife of one of them, was quartering at the time. They were nearly all Kansans, most of them being from Dodge City, then the buffalo-hide capital of the world.

In the bloody fight that followed, Dixon and his fellow hunters beat off the Indians with heavy losses and held them at bay until help came from Dodge City. During this siege, Dixon made one of the most celebrated shots in the history of the West. At a distance of nearly a mile from the fort, which the buffalo hunters were defending, is a steep bluff. Observing some Indians watching them from the top of this acclivity, Dixon decided to try a shot at them. He took careful aim and pulled the trigger of his big “50” buffalo gun. Incredible as it may seem, the bullet struck its target, and an Indian fell from his pony, to be carried away by his friends. In later years, a state surveyor measured the exact distance from the bluff to the fort and found it was 1,538 yards, not far from seven-eighths of a mile.

A few months later, Dixon, while traveling with a small party with dispatches from General Nelson A. Miles, then camped on McClellan Creek, to Fort Supply, was surrounded by a war party of approximately 100 Kiowa and had to fight for his life in a buffalo wallow. At the party were Amos Chapman, another scout, and four soldiers. One of the soldiers was killed, and every man in the party was wounded more or less seriously, but they succeeded in repulsing the Indians and holding them off until help came. Dixon rescued his friend Chapman from under the very guns of the Indiana during the fight. Every member of the party received the Congressional Medal of Honor for their bravery. Dixon died in 1913. He had taken up ranching near the scene of the Adobe Walls fight and was successful.

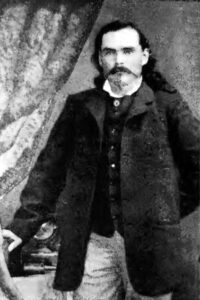

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was another Kansas product. Although his chief fame arises from his exploits as a gun-fighting marshal in various frontier towns, he was long a scout and a good one, too. He had an adventurous experience as a scout in the Union army during the Civil War and later on the plains. Custer speaks of him with high praise.

Wild Bill was born in Illinois, but like the others described in this article, came early to Kansas, then the very focus of adventurous frontier life. He served as an attendant at a stage station, during which time the much-publicized “McCanles gang” fight is said to have taken place. Whether or not this fight occurred exactly as has been told, the fact remains that Hickok became one of the greatest of plains celebrities.

After his Civil War experience, he returned to Kansas and spent the rest of his life there. He scouted for Hancock and Custer, then served as marshal of several successive towns, including Abilene, Fort Hays, and Dodge City, before being shot down from behind at Deadwood, South Dakota, in 1876.

Another Kansas scout whose career was the subject of much controversy was William F. Cody, known to hundreds of thousands as “Buffalo Bill.” Whether or not he killed the numerous Indians he claims to have slain in his autobiography, he was certainly employed as a scout by many officers, including Carr, Sheridan, and Miles. He, therefore, must have been efficient and able in that line. Cody was reared near Leavenworth and rode pony express before his scouting and buffalo-hunting days. He became world-famous as a circus man and will probably always remain an almost legendary figure of the frontier.

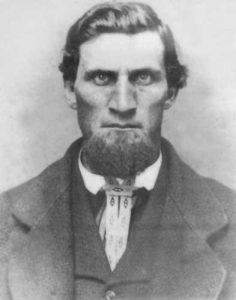

Compared with little else, William E. Mathewson is known for being an associate and friend of Kit Carson and for providing essential scouting services to the government. Mathewson, of Scotch descent, trapped all over the Rockies in the days before there was any thought of settlement. Later, he traded among the Indians in western Kansas for years. In 1853, he established a post known as the Cow Creek Ranch on the great bend of the Arkansas River.

It was here that Mathewson earned the Kiowa name Sillpah Sinpah, signifying “Long Bearded Dangerous Man,” from his treatment of the celebrated chief, Satanta, who attempted to help himself to a part of Mathewson’s trade stock without paying for it. Mathewson gave the Indian a terrific beating with his fists and ended by kicking him and his friends out of the store room. Strangely, the incident made a life-long friend out of Satanta, who rode hundreds of miles to warn Mathewson when the Kiowa went on the warpath in 1864.

On June 20, 21, 22, 1864, Mathewson and five employees in the Cow Creek Ranch fought a three-day battle with an overwhelming force of Kiowa who surrounded them. Finding they could not carry the fort, the Kiowa turned their attention to a wagon train which came into the vicinity, bound for New Mexico, laden with government ammunition and guns. Mathewson had been notified of the approach of the wagon train and its freight several days before. But for some reason, the 150 men and boys in the train did not know they were carrying munitions.

When the Indians attacked, they at first could scarcely defend themselves from lack of arms, but Mathewson, seeing their danger, leaped upon his horse and rode right through the Indian lines into the wagon enclosure. Under his direction, some of the boxes of guns and ammunition were opened, and the hostiles soon were made to realize that they had better retreat.

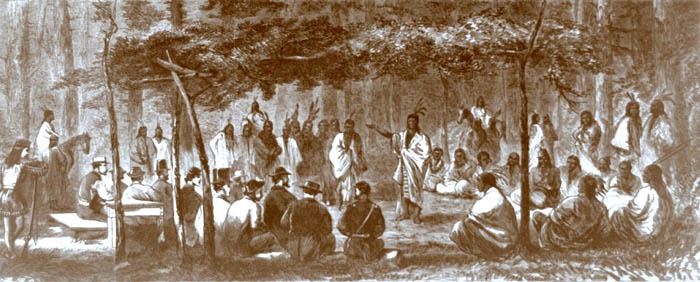

In 1864, Mathewson rode as a scout for General James Blunt’s expedition. Later, he did much to bring the Indians together for the Little Arkansas treaty, which preceded the Great Medicine Lodge Peace Council.

When the government wished to treat with the Indians and move them out of Kansas into the Indian territory, it was Mathewson who went out at the risk of his life and visited band after band and induced them to attend the council. His son, William Mathewson, Jr., told the writer that Mathewson’s chief danger in this perilous work was that he would be shot before he could identify himself to the Indians. Once he was known to them, he was always received gladly, because his reputation among them as an honest and generous trader was universally accepted.

In approaching a village, Mathewson made a practice of creeping up close to it, so that when he suddenly revealed himself, he was close enough to be recognized, his son says. Mainly through his efforts, the great concourse of tribes was gathered at Medicine Lodge, with the results recorded by history.

It was Mathewson, incidentally, who first bore the title of “Buffalo Bill,” due to his prowess in killing buffalo for starving settlers in 1860. This title was later conferred upon Cody through the “generosity” of Ned Buntline, the dime-novel writer, who came west to write his particular type of lurid literature. In an interview printed in a newspaper now in the possession of William Mathewson, Jr., Cody acknowledged that Mathewson was the “original” Buffalo Bill.

Among Mathewson’s exploits was the rescue of the two Kirkpatrick girls, Helen and Louisa, from captivity among the Indians. Through his influence with the savages, he is said to have made arrangements for the release of no less than 54 women and children during his years on the frontier.

Mathewson’s extreme reticence and modesty were such that he never would talk to newspaper men or relate his adventures except on rare occasions. He is deserving of a much greater place in history than he has thus far received.

These are only a comparative few of the Kansans who won fame as Indian scouts. Even the great Kit Carson got much of his experience in this state. His first Indian fight was in Kansas, and Pawnee Rock is said to have been named by him in honor of a brush with that tribe which took place there. He spent much time at Bent’s fort, almost on the present Kansas-Colorado border, and made many trading trips into Kansas. On one occasion, with two other trappers and three Delaware Indians, he was surrounded by Comanche in the southwestern corner of the state, and there fought one of his most spectacular battles.

Ben Clark, Amos Chapman, California Joe, Billy Peacock, and John Cook — all spent some part of their lives in Kansas. And so it was with many others. Kansas furnished the scouts who formed the vanguard in the wars that brought civilization to the West.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, August 2025. Source: Wellman, Paul I.; Some Famous Kansas Frontier Scouts; Kansas State Historical Quarterly, August 1932 (Vol. 1, No. 4), pages 345 to 359.

Also See:

Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men