On July 13, 1951, one of the most costly floods in Kansas’ history swept down the Kansas River Valley into the Missouri River basin. Though the Kansas River Valley had flooded before, it had never been with this magnitude and damage.

In May in Hays, Kansas, the flood began after 11 inches of rain in two hours, flooding Big Creek. When the creek overflowed, it sent water pouring into the Fort Hays State University campus to a depth of four feet. One professor and his seven-year-old daughter died when their home caved in. All records at the college were ruined, the graduation ceremony was canceled, and graduates were mailed their diplomas a month later.

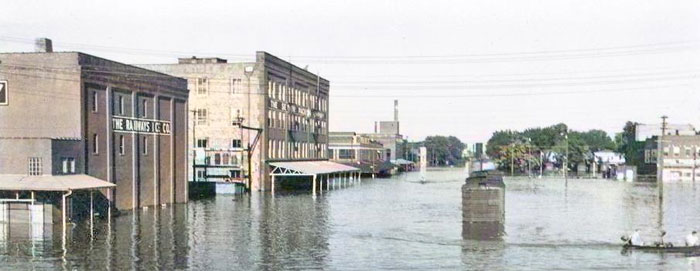

From July 9-13, some areas in the Kansas River basin received 18.5 inches of rain. Called Black Friday, July 13, flooding started above Manhattan on the Big Blue River. The Manhattan business district was eventually covered with eight feet of water, and two people were killed. Downstream flooding continued in Topeka, Lawrence, and Kansas City. In Topeka, about 7,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, and 24,000 people were evacuated. The rising river washed away roads, and railroad tracks moved, causing transportation throughout the river basin to halt. Communication lines were downed.

The flooding caused other rivers to flood downstream, including the Kansas River, Missouri River, Neosho, Marais des Cygnes, and Verdigris River basins. Altogether 116 cities and towns were affected, and 10,000 farms also suffered damage. In Kansas City, the flood damaged the industrial area destroying packing plants, the Kansas City Stockyards, warehouses, grain elevators, and factories near the second-largest rail center in the nation.

The damage across eastern Kansas and Missouri exceeded $935 million, killed 28 people, and displaced 518,000 more. Over a million acres flooded, 2,500 homes were completely demolished, 336 businesses were destroyed, and more than 3,000 flooded.

The crest continued downstream through Missouri, passing through Boonville, Jefferson City, Hermann, and St. Charles, resulting in further flooding.

On July 17, President Harry Truman toured the damage by airplane as far west as Manhattan and declared the disaster “one of the worst this country has ever suffered from water.”

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the federal government proposed building flood control dams along tributaries of major rivers in Kansas. As part of the New Deal program, these projects would have provided jobs for unemployed workers and prevented downstream flooding. Though the construction of Tuttle Creek Reservoir above Manhattan was proposed, no action was taken due to a lack of funding. However, the Flood of 1951 would change that.

After businessmen and residents living downstream along the Kansas River increased the pressure on government officials, the Tuttle Creek Reservoir was finally approved. In 1952, the government began acquiring the surrounding farmland to erect the dam.

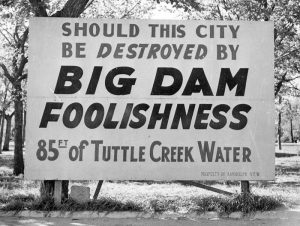

However, the project faced heavy opposition from local landowners. It would displace 3,000 people and ten towns, including Stockdale, Randolph, Winkler, Cleburne, Irving, Blue Rapids, Shroyer, Garrison, Barrett, and Bigelow. Transportation facilities, including two railroads, would have to be abandoned or moved along with numerous state highways and county roads. Approximately 55,000 acres of fertile farmland would be inundated.

The citizens of the Blue River Valley, north of Manhattan, soon began a campaign to save their farms, many of which had been in the valley for generations. Though everyone agreed flood protection was desperately needed in Kansas, the disagreement lay with constructing a large reservoir in prime farmland. Labeling the Tuttle Creek Dam project as “Big Dam Foolishness,” they delayed construction from December 1953 until December 1955 through vigorous campaigning, letter writing, and public debate. However, the Corps of Engineers continued to acquire thousands of acres through purchase and condemnation.

In the end, Tuttle Creek Dam and reservoir were built at the cost of over 80 million dollars. Though the dam did not completely stop the flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers estimates that Tuttle Creek Lake has prevented over three billion dollars in flood damages since its opening.

“Black Friday,” July 13, 1951, still remains the single greatest day of flood destruction in Kansas. The Kansas River was so full that it forced the waters in its tributary, the Big Blue River, to run backward.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated July 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

Big Dam Foolishness

Kansas State Historical Society

Wikipedia