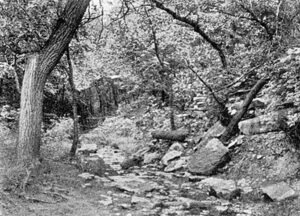

Chingawasa Springs, located in a beautiful natural park in the northeastern part of Marion County, Kansas, was once named Carter’s Mineral Springs. Within a quarter-mile radius, there were about 30 springs that bubble out of the bluffs, the water flowing from them forming quite a stream.

The springs were mentioned in Lieutenant Zebulon Pike’s 1806–1807 Expedition journal.

This group of several springs was renamed in the late 1800s after Osage Indian Chief Chingawassa, meaning Handsome Bird. Chingawassa was known to have often camped by the springs with his tribe. Chief Chingawassa was an honest, friendly chief who signed two treaties with the United States Government — one in St. Louis, Missouri, on June 2, 1825, and a second at Council Grove, Kansas, on August 10, 1825.

According to local legend, Chingawassa was murdered by a jealous Kanza Indian chief and was later buried near the springs by his avenging tribesmen.

In the 1880s, a young stonemason named Walter Sharp owned the land and was convinced that coal lay below his land. He sold his house to raise enough money to hire a well-driller to find the coal. However, the drill stopped after going down 100 feet, and Sharp found nothing but murky water. Sharp was determined to salvage the money, and after a friend told him it smelled like water from a mineral spring he had been to, Sharp began bottling it and selling it as a medicinal solution.

At that time, mineral springs were very popular due to their alleged healing qualities, and before long, numerous people were coming to his land to partake of the medicinal waters. Sharp then erected buildings and facilities to accommodate them.

When Dr. George L. Piper, an experienced physician, heard the news about Sharp’s spring, he offered to lease it from Sharp. When the two men agreed, Dr. Piper began investing in the site, building a resort. Described as an “intelligent, affable gentleman,” Dr. Piper promised that his Chingawassa waters cured “rheumatism, paralysis, skin and blood diseases, kidney and liver complaints, chronic constipation, hemorrhoids, nervous conditions, and more.

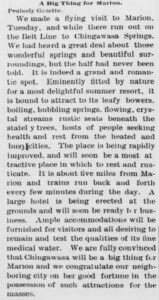

Confidence spread that Chingawassa Springs would be a boon for the town, stoked in no small part by Dr. Piper himself. On July 27, 1888, he wrote a letter to the Record newspaper describing the many conditions his healing waters could relieve.

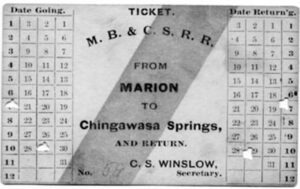

In 1888, the Marion Chingawassa Belt Line was built by Levi Billings. The 4.5-mile railroad spur began at the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad station at Marion and ended at Chingawassa Springs, about four miles to the northeast. In the meantime, a large summer hotel and a dance hall. In front of the hotel, a large depot and “eating house” were erected.

The Record grows more and more confident that this mineral water is to make Marion famous as a sanitarium and widely noted as a health resort.”

— Marion Record, March 16, 1888

The resort operated from the beginning of May until October. The new taxpayer-funded rail line spur line opened on July 4, 1888. With a ticket from Marion to the spring costing a dime, the train gave 2,500 passengers round-trip rides. The cash receipts for that day set a record for the line of $500.00 that would never be beaten. One stop on this journey was the historic Elgin Hotel. The train would also stop anywhere along the line to pick up or drop off passengers.

Both the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad and the Chicago and Rock Island Railroads offered round-trip fares from Chicago and other cities to Chingawasa Springs.

The Chingawassa Springs Health Resort also boasted a supervising physician, and walks and rustic bridges were built for people’s enjoyment.

During the fall and winter, the train hauled stone out of quarries both east and west of Marion and hauled grain to market.

While the first season of the resort proved a success, the novelty soon wore off, and revenues began to fall, proving that Marion’s population of just over 3,000 was not large enough to support the spring’s operations. After a few short seasons, the economic panic of 1893 brought the enterprise to an abrupt halt. Afterward, the buildings were dismantled, several train cars were converted to other uses, and the railroad cross-ties were sold to a farmer for fence posts. The tracks were removed in 1910.

The springs area continued to be used for recreational outings for many years.

Today, the site is inaccessible to the public and sits within a cattle pasture.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated August 2025.

Also See:

One of the Chingawassa Belt Line train cars became the Owl Cafe in Marion, Kansas. It is gone today.

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Vol I; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Elgin Hotel

Humanities Kansas

Marion County Record

Prairie Gal Cookin