Fort Harker, Kansas by Alexander Gardner, 1867.

Beginning of this Period. Nearly three score years have passed since the close of the Civil War, a period of work, growth, and progress. The earlier years in Kansas were but a time of preparation, and with the war’s end, the people were finally free to turn their attention to farming or other occupations. Hundreds of new settlers poured into the state each year. Little pioneer homes dotted the eastern part of the state more and more thickly, and the line of settlement rushed westward.

Indian Troubles on the Frontier. As the white-topped wagons of the immigrants became more numerous, the Indians and the buffalo were pushed farther on. But the red man did not give up his hunting ground without a struggle. The encroachments of the settlers had long been resented. Even before the close of the Civil War, while the soldiers were needed elsewhere, the Indians had begun their depredations on the frontier. In 1865 and 1866, settlements were attacked in Republic and Cloud Counties, the stock was driven away, much property was destroyed, and several people were killed. The few settlers on their scattered claims were poorly armed, and, with no soldiers near to protect them, they were in constant fear of wandering tribes of hostile Indians.

Open War with the Indians. The following year, United States troops were sent to protect the frontier. They drove the Indians back and destroyed one of their villages. This only made the red men eager for revenge, and they began an open war on all settlers, immigrant trains, traders, and travelers. Robberies and murders were committed along the frontier, particularly in the Republican, Solomon, and Smoky Hill Valleys and in Marion, Butler, and Greenwood Counties. Travel over the Santa Fe and other westward trails almost ceased, and the line of settlement was pushed eastward many miles. Many tribes engaged in these attacks. They dashed into the state from north, South, or west, committed their cruelties, and were gone.

The Broken Treaty. At one time, the Government made a treaty with several tribes, and they were removed to a reservation in the Indian Territory. Still, they were to have the privilege of hunting in Kansas as far north as the Arkansas River and be provided with arms. They kept their promise of peace only until they could get ready for another attack, and while part of them was being supplied with arms at one of the forts, the rest were engaged in a most heartless and bloody raid on the northwestern settlements.

The Indians were Subdued. This led Governor Samuel Crawford to organize several Kansas Volunteer companies and ask for more United States soldiers. Later, a regiment of Kansas volunteer cavalry was called for, and on November 4, 1868, Governor Crawford resigned from his office to take command of the Nineteenth Regiment. After considerable fighting, the Indians were finally subdued, and by 1870, the trouble had practically ended. There were a few outbreaks from time to time, but none of them were severe. During this contest, which had lasted from 1864 to 1869, the lives of more than 1,000 Kansas settlers had been lost, a great deal of property had been destroyed, and the westward movement of settlement had significantly been retarded.

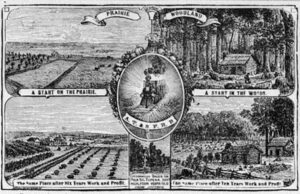

The Homestead Law, 1862. Shortly after the admission of Kansas to the Union, Congress passed a measure that had a tremendous effect on the state’s growth. This measure was the Homestead Law, passed in 1862. This law provides that any person who is the head of a family, or who is 21 years of age, and who is a citizen of the United States or has declared his intention to become such, may acquire a tract of 160 acres of public land on condition of settlement, cultivation, and occupancy as a home for five years, and on payment of specific moderate fees. It also provides that any settler’s time in the army or Navy may be deducted from the five years. Previous to 1862, settlers bought their claims of the Government. The liberal provisions of the Homestead Law attracted thousands of settlers to Kansas. Many of the newcomers were young men who had been in the army.

Many were foreigners who had recently arrived in America, while thousands of others came from the eastern or central states. Nearly all of them were poor, with scarcely enough to provide for themselves until the harvesting of their first crop. But they were full of hope and ambition and willing to endure the toil and privations of pioneer life to make their dreams of a home on the Kansas prairies a reality.

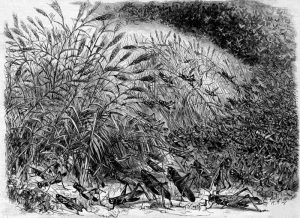

Many Droughts in the Early Years. The task of turning the bare plains into fertile fields was heavy, and the brave people who began it endured many hardships and encountered many discouragements and disappointments. Severe droughts were frequent in the early days, and hot winds often swept across the country. The year 1869 was dry, and crops partially failed. In 1874, a long dry spell followed, followed by a scourge of grasshoppers in late summer.

The Grasshopper Invasion, 1874. At different times, there had been invasions of grasshoppers in the country west of the Mississippi River, but none were as disastrous as the one in 1874. The grasshoppers, a type of locust, came into the state from the northwest and moved toward the southeast. The air was filled with them. They covered the fields and trees and destroyed everything green as they went. They left ruin and desolation in their pathway. In the western counties, where the settlements were new, and the people had no crops to depend upon, the result was much like that of the terrible years of 1859 and 1S60. By the time of the invasion, there were more people, more provisions, and more money, and the state could do much to help the thousands of its citizens who were left destitute. It became necessary, however, to accept aid from the East again, and thousands of dollars and many carloads of supplies were distributed to people in need. Never since has Kansas had to ask for help.

Later, Kansas generously gave to sufferers in other states and other lands. This visit of the grasshoppers was prolonged into the following year, for they had deposited their eggs in the ground, and the following spring, large numbers of young grasshoppers hatched. These destroyed the early crops, but for some unaccountable reason, they soon rose into the air and flew back toward the northwest when the swarms of the year before had come. There was still time for late planting, and the crops of 1875 were abundant.

Prosperous Years Followed the Grasshopper Invasion. The arrival of the grasshoppers temporarily discouraged immigration, but prosperous years followed, and people were again attracted to Kansas. More of the prairie was turned into farms, new towns sprang up, the country became more thickly settled, railroads, schools, and churches were built, new counties were organized, and the old stories of “The Great American Desert” were gradually forgotten. Kansas was taking her place among the states.

Life of the Early Settlers. So that this excellent result might be accomplished, that the Kansas of today might be, a generation of men and women had to conquer these vast prairies that were swept by blizzards, parched by droughts, scorched by hot winds, and scourged by grasshoppers. A few pioneers gave up and returned to their old homes, but most of them were of the sturdy type and remained, always believing that the day of better things was to come. Though they had little money and few of the comforts and conveniences of life and were often homesick for the friends and scenes they had left behind, they stayed and worked and hoped. Volumes could be filled with stories of those brave people’s hardships and sorrows, mothers who died from overwork or exposure or lack of care, children who sickened from want of proper food, and homes swept away by prairie fires, and of homesteads mortgaged and lost.

The Pleasures of Pioneer Life. But this is only one side. Pioneer life was not all dark. Most people were strong and healthy, and the outdoor life with plenty of exercise and simple food kept them so. Although there was deprivation and hard work, there was also much pleasure. Ask any old settler whether the people had good times in those days, and you will hear tales of spelling schools and singing schools, literary societies at which debating was an important feature, and of the country dance with its old-time music on the fiddle. These affairs were attended by young and old from miles around; a trip of ten to 15 or even 20 miles was not unusual. Buggies were scarce, and most settlers went on horseback or farm wagons that did not always have spring seats. Quilting and husking bees, house warmings, and camp meetings were other events of the early days. Since there were no telephones and it was often days from one mail to another, pioneer families counted it a pleasure to “visit around” and exchange the news. Those were the days of real hospitality; the “latch-string hung out at every door,” and all were welcome to enter. No house was too small, nor no food supply too scanty for the entertainment of friends or wayfarers. Those were the days, too, when the children often waited for a “second table” or stood up to eat because there were not enough chairs for all; when the boys wore high-topped boots, the girls wore sunbonnets, and a calico dress was good enough for almost any occasion.

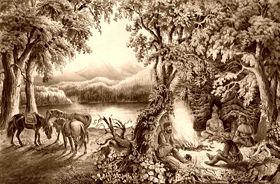

Buffalo Hunting. In the early years, the buffalo hunt was one of the pioneers’ pleasures. In the fall, parties of men with their teams and hunting outfits would set out for the buffalo range to secure a supply of meat for the winter. They were usually successful in finding buffalo, antelope, wild turkey, and occasionally elk or deer.

Extermination of the Buffalo. Remarkable stories are told of the great numbers of buffaloes still roaming our western prairies 50 years ago, stories of herds miles in width moving across the country. With the onrushing tide of immigration, the buffalo rapidly disappeared. Within little more than a dozen years after the close of the Civil War, there were practically none left. This was not because they were used as food but because they killed them for their hides. Large numbers were slaughtered and skinned, and the bodies were left on the plains. The hides were shipped east by carloads, where they were sold to make robes.

Selling Buffalo Bones. In a few years, the prairies were thickly strewn with bleaching bones, and these, too, were gathered up and shipped east, where they were ground into fertilizer to be used on worn-out farms. These bones brought from $6 to $10 a ton, and money earned in this way served to tide many a homesteader through the winter. It has often been regretted that the Government did not take measures to restrict the killing of the buffalo, but the danger of extermination was not realized until too late.

The Trappers. A great deal of trapping was done, especially by the younger men. Often, several of them would make up a party and, with guns, traps, and a winter’s supply of provisions, start for a favorite trapping ground, where they would make a camp along some stream. Sometimes, the camp was a tent, but more often, it was a dugout in the bank with the front part made of logs. Along the streams, they caught chiefly the beaver, the otter, the raccoon, and the wildcat; on the prairies, the big gray wolf and the coyote. The busy days were filled with visiting the traps, caring for the pelts, chasing wild game, and keeping an alert watch for Indians. When spring came, and they turned homeward to work on the farms, they often carried several hundred dollars worth of furs.

The Exodus, 1878-1880. The population of Kansas was gradually built up from many sources, but until 1878, there were not many African Americans in the state. That year, a movement among the people of color to migrate to western and northern states began in some southern states. So many thousands left the Southland that the movement came to be called “The Exodus.” It is not strange that the state famed for its fight for freedom should attract many ex-slaves, or the “Exodusters,” as they were called. During 1878-1880, several thousands of black people arrived in Kansas. A few had teams and some farm implements; some had a scanty supply of household goods, but many had nothing and had to be given aid. Very few homesteaded land, others found employment as farm hands, and the rest settled in different state towns.

The Kansas Boom in the 1880s. The ten years following the grasshopper invasion of 1874 were all good years. The rains fell, and crops flourished. It was a period of remarkable growth and prosperity. During these years, the railroads made special efforts to bring settlers into the state, and Kansas was widely advertised. Reports of the opportunities here stimulated immigration, and settlements overspread the western prairies. Great confidence was felt in the state’s future, and people in the East eagerly invested in Western land and property. Money was easy to borrow, and the Kansas people borrowed liberally and began speculating in real estate. Kansas was soon “on the boom.” Property was bought, not to use, but to sell again at a higher price. Cities and towns laid out additions divided into lots and sold for large sums. Expensive improvements were made, and public and business buildings were constructed that were far more extensive and more costly than the needs of the time demanded. Railways and street-car lines were built without business enough to support them. Hundreds of new towns were mapped out, and the lots sold. Many of these towns never existed except on paper; others were later turned into pastures or cornfields.

Collapse of the Boom, 1887. Since the new settlers were unfamiliar with Kansas’s soil and climate conditions, many selected land not adapted to agriculture. Therefore, much of the farming was not profitable. In 1887 came one of the country’s most severe droughts ever known. The people lost confidence in Kansas, and the boom collapsed. Eastern people wanted their money back, but there was nothing with which to pay them. Money could not be borrowed, and mortgages were foreclosed. People who had bought property at high prices, expecting to sell at a profit, found themselves unable to sell at any price. Many who had counted themselves wealthy found their property almost valueless. Banks and business houses failed, and hundreds of people were ruined. Thousands left Kansas, some of the western counties being almost abandoned. The year 1887 was followed, however, by several good crop seasons. Much attention was given to studying farm conditions, and Kansas began progressing again.

The Opening of Oklahoma. In 1889, Kansas lost about 50,000 of its population. This came about through the opening of Oklahoma to settlement. The President issued a proclamation setting high noon of April 22 as the time the settlers could enter the new country to take claims. The opening of Oklahoma had been anxiously awaited for years. As the appointed time drew near, people from all parts of the United States began to assemble along the southern line of Kansas. Arkansas City was the chief gathering place, for, at this point, one railroad line entered Oklahoma. When, at noon on April 22, the cavalrymen who patrolled the borders fired their carbines to signal that the settlers could move across the line, a great shout went up, and the race for claims began. Hundreds crowded the trains, thousands rode on fleet horses, many rode in buggies and buckboards, others in heavy farm wagons, and some even made the race on foot. In the morning, Oklahoma was an uninhabited prairie; at midday, it was a surging mass of earnest, excited humanity; in the evening, it was a land of many people.

Within a few days, the breaking plow turned the sod on many homesteads while merchants, bankers, and professional men carried on their business in tents or rough board shanties. The rush of settlement to Kansas was remarkable, but the settlement of Oklahoma is the climax in the story of American pioneering. Although Kansas furnished many Oklahoma settlers, immigration to our state from the East soon made up for the loss.

The Panic of 1893. In 1893, a financial panic extended across the country, accompanied in Kansas by a partial failure of crops. Those were dark days in Kansas, for many people were still burdened with heavy mortgages. But this period should be remembered as our last “hard times.” Within two or three years, conditions significantly improved. The 25 years following that time brought almost uninterrupted prosperity.

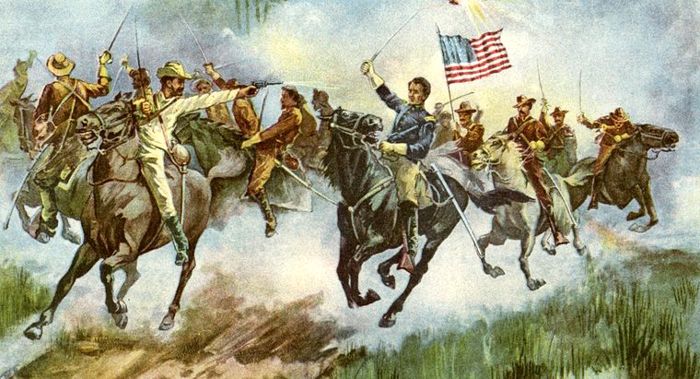

Kansas in the Spanish-American War. In 1898, the country enjoyed a long period of peace since the Spanish-American War broke the Civil War. The call for soldiers was eagerly responded to in Kansas, and four regiments were raised. Our state had furnished 17 regiments during the Civil War and two for fighting the Indians. Therefore, the four for the Spanish-American War were numbered the Twentieth, the Twenty-first, the Twenty-second, and the Twenty-third. The Twenty-third was composed of colored soldiers. The only one of these regiments called upon to do any fighting was the Twentieth, which was ordered to the Philippines. Under a Kansan, Colonel Fred Funston, the men of this regiment took part in the following campaigns. He credited themselves and their state much for their bravery and efficiency. The Twenty-third was sent to Cuba. The other regiments were trained and kept in readiness, but the early end of the war prevented their active service.

The Spanish-American War.

The State Capitol. The year 1903 is an interesting one, for it marked the completion of our State Capitol. Shortly after Kansas was admitted to the Union, the people selected Topeka as the seat of Government. As soon as the Civil War was over and they had time to consider public improvements, they began to lay plans for building a capitol. Every state has a capitol or state house, as it is often called, in which there are offices for the Governor and other state officers and large rooms for the meetings of the Legislature. It is for the state what a courthouse is for a county. It should, of course, be a fine building of which the people can be proud. But in the 1860s, Kansas people were few and had little money. They could not afford to build a capital that would be large and handsome enough for the future, nor did they wish to construct a small, cheap building that would have to be set aside later. Instead, they planned a fine structure to be built a little at a time as they could afford it.

The Capitol building, locally often called the Statehouse, of Kansas in Topeka. Photo by Carol Highsmith.

In 1866, the Legislature provided for the erection of our state house’s east wing. As the state grew in wealth and population, more money was appropriated occasionally for constructing other wings, the significant central portion, and the high dome that reached nearly 300 into the air. The building was completed in 1903, having been 37 years in the making. It grew as the state grew, costing between $3,000,000 and $4,000,000. The great State of Kansas should now have one of the finest capitals in the United States.

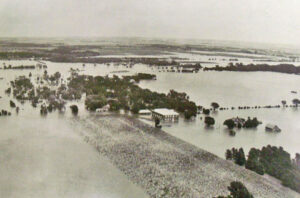

The Floods. The people of Kansas had withstood several droughts, but beginning in 1903, they were, for the first time, visited by a series of floods. The first one was probably the most destructive. Most of the water came down the Kansas River from the tributaries draining central and western Kansas, where there had been heavy rainfall. Farms and towns along these streams were flooded, property was swept away, and several lives were lost. Topeka, Lawrence, and Kansas City, where portions of the cities were inundated for days, suffered heavy losses. The following year, nearly every stream in the state poured a flood of water down its valley, and many people had to flee to the hills for safety. In 1908, high water again visited Kansas for the third time in five years. The loss occasioned by these floods amounted to many millions of dollars, but help poured into the sufferers from many sources, and they straightway began repairing and rebuilding. In a short time, all traces of the calamity had disappeared.

Stories of floods in Kansas have been handed down from far-off Indian days, but the earliest flood of which there is any account was in 1844. The Indians told the white men about it and advised against building close to the rivers, but no attention was paid to the warning. Since the recent floods, however, several people have moved back from the streams. A few cities, including Topeka, Lawrence, and Kansas City, have built dikes, bridges have been lengthened to give streams more room, and several railroad grades have been raised above the danger line.

Kansas in 1920. While the floods caused much loss and suffering, the state’s resources had become so great that general prosperity was not seriously affected. Each year has added to the prosperity and progress of the state; until now, Kansas has been one of the great states of the Union. We have only to look about us to see how marvelous conditions have changed since our pioneer days. Great fields and orchards are spread over what was once the Indians’ hunting ground, and cattle have replaced the roving herds of buffaloes. Tractor plows now turn the soil where there was only buffalo grass, thriving towns and cities once stood where the tepee stood, and shining steel rails mark the paths of Indian ponies and emigrant trains. All these things have been done within a single generation. Thousands of the men and women who came into Kansas in their wagons and drove across the unfenced plains are still among us, but now, when they journey over the same country, they go in swiftly moving trains or automobiles. Once they saw only the prairie and a few settlers’ cabins, they now saw roads and bridges, farms and ranches, stores, banks, mills, mines, and factories. They see what they have helped build, a great state, and they may be proud of it. Their unconquerable faith, courage, and unremitting toil made Kansas what it is today.

Government of Kansas. As the pioneers look at their state, they may feel pride not only in the acres that have been brought under cultivation and the wealth that has been produced but also in a government that is one of the most advanced in the Union. Many measures have been passed to promote the welfare of the people. Among the important ones are the child labor law, the truancy law, the anti-cigarette law, the law providing for juvenile courts, laws about public health, the fire escape law, the “blue sky” law, the primary-election law, and the law governing public utilities. These are only a few, but among the hundreds of measures that have been passed affecting the character of our Government, none stand out more prominently than the two amendments to our Constitution providing for Prohibition and women’s suffrage.

Prohibition in Kansas. Temperance was a live topic in Kansas from the beginning; even in Territorial days, laws were passed that tended to regulate, to some degree, the liquor traffic. During the first 18 years of statehood, a constant increase in sentiment favorable to Prohibition existed. In 1880, during the administration of Governor John P. St. John, the people voted to adopt the following amendment to the Constitution: “The manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors shall be forever prohibited in this State, except for medical, scientific, and mechanical purposes.” The law has been strengthened occasionally, and more attention has been given to its enforcement until today. Kansas is one of the strictest prohibition states, and the popular sentiment against using liquor is stronger here, perhaps than anywhere else in the United States. For many years, Kansas stood almost alone as a prohibition state. Still, in recent years, the number of prohibition states has increased rapidly, and in 1918, Congress offered a prohibition amendment to the National Constitution. In 1919, it was ratified by the necessary two-thirds of the states. Kansas was among the number. It is a matter of pride in Kansas that ours was a pioneer state in this great movement.

Women’s Suffrage. Kansas was one of the most liberal states in its laws concerning women’s rights, but only in the early 20th century did Kansas women have full political rights. In 1861, women were given the right to vote in district school elections, and in 1887, in city elections. The question of complete women’s suffrage was voted upon and defeated in 1867 and again in 1894, but in 1912, it carried by a large majority. Only six states — Colorado, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, Washington, and California, preceded Kansas in granting women the right to suffrage. Several other states followed Kansas, and in 1919, Congress offered to the states for ratification a Women’s Suffrage amendment to the National Constitution.

Kansas in the World War. The period from the opening of the 20th century to the beginning of World War I was, on the whole, one of peace and prosperity in Kansas. No great destructive force, such as famine or panic, left the people struggling for existence, nor did anything occur to stir their deeper emotions. Their chief interests were building their homes and businesses and developing their state. But suddenly, in 1914, like the people of the rest of the United States, they began to give more thought to the affairs of other countries, and when on April 6, 1917, the United States entered the war, the people of Kansas were ready to carry their share of the burdens.

The state’s young men began to offer their services in the National Guard, the regular Army, and the Navy. More than 18,000 of these volunteers were there. Within a few weeks, Congress passed the Compulsory Service Act, under which approximately 42,000 Kansas men were called into service during the war. The National Guard, numbering about 10,000 men, was soon called. Altogether, there were 70,000 Kansans in the United States forces. These men were sent to practically every organization in the army. However, the more significant portion was in the 89th National Army Division, the 10th Regular Army Division, the 35th National Guard Division, and the 117th Ammunition Train of the 42nd Division. All of these except the 10th Division, which had not yet completed its training when the armistice was signed, were sent to France, where they took part in important engagements and bore themselves bravely, notably the Rainbow Division in the last battle of the Marne, the 89th at St. Mihiel and the Argonne, and the 35th Division in the Argonne drive. Many of our young men went into special service branches, such as the Air Service, Railway Engineering, Signal Corps, Quartermasters Corps, and Ordnance Corps. The Federal Government established two Officers’ Training Camps in Kansas, Fort Riley and Fort Leavenworth. Many Kansas men attended these camps and received commissions. Hundreds of young women from Kansas rendered skilled and devoted service as nurses in training camps and overseas. The state’s people actively participated in various kinds of war work and subscribed more than their quota to all appeals for funds and all bond issues. Altogether, Kansas played its part in the war with its accustomed loyalty and spirit.

Summary. The years after the Civil War were eventful ones. The Indian troubles on the frontier lasted from 1864 until 1869. Much property and more than 1000 lives were lost. National troops and a regiment of Kansas soldiers were required to quell the trouble. Governor Samuel Crawford re-signed his position and took command of the Kansas troops. From 1878 to 1880, thousands of African Americans arrived in Kansas. This movement from the South was called the “Exodus.” The grasshopper invasion in 1874 was followed by ten years of prosperity. Then came the boom, which was ended by the drought in 1887. Eastern moneylenders held thousands of Kansas mortgages, and though several good crop years followed, the state had not yet recovered when the panic in 1893 brought renewed trouble.

Good crops followed, and Kansas soon entered a period of prosperity that has continued to the present time. Kansas furnished four regiments for the Spanish-American War in 1898 and made the most of every opportunity to serve in the World War in 1917-1918. The State Capitol began in 1866 and was completed in 1903. The years 1903, 1904, and 1908 were the flood years. Among the many critical governmental measures are the prohibition and woman suffrage amendments. Since the Civil War, Kansas has become a great and prosperous state.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated January 2025. Source: Arnold, Anna E.; The State of Kansas; Imri Zumwalt, state printer, Topeka, Kansas, 1919.

Also See: