By the Federal Writers Project, 1939.

Before the arrival of the Spanish in 1541, Kansas was known only to the nomadic hunter-warrior bands and to the indigenous tribes of the region. Of the latter, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado mentions three, the Wichita, Kanza, and Pawnee, and vaguely inferred that there may have been more.

For a decade, Spanish conquistadores had been thinking about the “Seven Cities of Cíbola.” Many adventurers cherished the hope of finding and plundering these supposed centers of wealth. However, only Coronado, the Governor of New Galicia in New Spain, Mexico, came into the Quivira quest. This quest arose from the disappointing Cibola experience and is the colorful prelude to Kansas history.

Fray Marcos de Niza.

In 1539, Friar Marcos de Niza, whom Coronado had sent on a preliminary search for the Cibola cities, returned with the good news that he had spied one of these incredible places of “high houses,” though only from a safe distance. An expedition was organized, and 300 Spanish “men of quality” gathered at the rendezvous point at Compostela on the Pacific coast of Lower California in 1540. With Coronado as captain-general, the army started northward, crossed the mountains, and spent that year in futile marches through Arizona and New Mexico. Winter overtook them at Tiguex, near present-day Bernalillo, New Mexico. By this time, they had determined that the cities of Cibola were merely poor pueblos. Still, one of Coronado’s captains, Hernando de Alvarado, while on a minor search, had been told by “an Indian slave” whom he called “The Turk” that far beyond “toward Florida” lay the slave’s land, Quivira, which was rich in gold and silver. He could guide the white strangers to it.

In April 1541, Coronado and his army left Tiguex, hoping to find the precious metals that Cibola could not supply in Quivira. The Turk led them through “the cow country” into western Texas, so far Southeastward that the captain-general at a village on the Colorado River called a halt. Their supplies had fallen dangerously low. For 37 days, they followed the Turk and lived mainly on buffalo meat to conserve their grain supplies. Tiguex was “250 leagues” away, and the unknown country beyond might prove barren. Coronado divided his force. With only 30 horsemen and six footmen, he headed north to pursue the quest, sending the remainder of his men back to Tiguex to await his return.

With Coronado went the Turk and another guide. Across the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, Coronado proceeded “until he reached Quivira.” His report of October 20, 1541, to his king reads: “I traveled for forty-two days after I left the force, living all the while solely on the flesh of the bulls and cows which we killed… and going many days without water and cooking the food with cow dung, because there is no other kind of wood in all these plains, away from the gullies and rivers, which are few.” The chronicler Suceso placed Quivira as “in the fortieth degree.” But another authority, mapping the “Province of Quivira,” puts it in the thirty-ninth, between the Arkansas River at Great Bend and the confluence of the Republican and Kansas Rivers at Junction City.

Later, Coronado heard that he had tried to incite the Quivira people (Wichita tribe) to kill them. The Turk might have been killed anyway, for, by this time, one fact was evident to the angry captain-general: Quivira contained no gold or silver. “These provinces,” Coronado wrote, “are a very small affair… There is no gold, nor any metal at all in that country.” But he found some satisfaction “on seeing the good appearance of the earth… The province of Quivira… 950 leagues from Mexico,” he conceded, “is the best I have seen for producing all the products of Spain, for besides the land itself being very fat and black, and being well watered by the rivulets and springs and rivers, I found prunes like those of Spain, and nuts and very sweet grapes and mulberries.”

After 25 days in Quivira, Coronado and his men returned to Tiguex by a shorter southwestward route, approximating what later became the Santa Fe Trail. In the summer of 1542, “with less than a hundred men,” he reached Mexico City, where he was shorn of his rank and soon died. However, the seemingly fruitless journey introduced the horse to the Plains and established Spanish claim in the entire western region by right of discovery.

A Franciscan monk, Juan de Padilla, who had been with Coronado in Quivira, returned to that country in 1542 but was killed by the Indians. For half a century, Spanish interest in the far north remained dormant. Then, in 1594, Francisco Levya de Bonilla and Antonio Gutierrez de Humana ventured beyond the Arkansas River, traveling northward for 12 days and reaching another river. On their way back, they were overtaken and murdered. Juan de Onate, in 1601, was the next Spaniard to traverse Quivira. More than a century probably passed before another Spanish party came so far north.

In the late 17th century, however, French Canadians began to show an active interest in the land west of the Mississippi River. In 1673, Louis Jolliet, a trader, accompanied by Father Jacques Marquette, descended the Mississippi River from the mouth of the Wisconsin River to below the mouth of the Arkansas River. On the return trip, they left the Mississippi River at the Illinois River. So it hardly seems likely that, as some suppose, Jolliet and Marquette ever reached the Kansas region. Neither did Sieur de La Salle, who, in 1682, descended the Mississippi River from the Illinois River to its mouth, returning along the same rivers. However, there is a Marquette map upon which some Kansas authorities seem to recognize certain topographical features that describe Kansas. It was probably drawn from information gained by interrogating Indians with whom the priest came in contact. In this way, Marquette learned much about native peoples he had never visited. On his map of the Missouri and Kansas region, he marked the names Ouemessourit (Missouriia), Kanza (Kaw), Ouchage (Osage), Paneassa (Pawnee), and some others.

In 1694, Canadian traders were among the Osage and the Missouri tribes. During the next few years, Spanish authorities in New Mexico received several indications that the French traders were on good terms with the Pawnee Indians. By 1706, when Juan de Ulibarri led a Spanish expedition from Santa Fe, it was apparent that the French, operating from the north, were becoming rivals to the Spanish of New Mexico for the interior trade.

Between 1706 and 1719, the French penetration was steady. In 1708, Canadians explored “three hundred to four hundred leagues” of the Missouri River. During the next decade, the French from the Louisiana capital extended their reach along other tributaries of the Mississippi River. In 1719, Charles Claude du Tisne, sent up the Missouri River by the Governor of Louisiana, visited the Osage villages near the mouth of the Osage River and crossed the northeast corner of Kansas to the Pawnee region on the Republican River.

The Spanish heard that “he planted the French flag in native villages and even traded in Spanish horses.” Don Pedro de Villasur, assigned “to drive the French out of the land,” left Santa Fe in 1720 with a Spanish force of 42 soldiers, three settlers, 60 Indians, and a priest. The route was “always to the northeast from Santa Fe.” Possibly, the caravan passed through part of Kansas. Still, the account mentions only three rivers: the Napestle (Arkansas River), the Jesus Maria (south fork of the Platte River), and the San Lorenzo (north fork of the Platte). Villasur and most of the Spaniards were killed in a battle thought to have been fought near North Platte, Nebraska. This defeat ended Spanish operations and left the French in undisputed possession.

The French established themselves more securely in the region in 1722 when Étienne Veniard de Bourgmont erected Fort Orleans near the mouth of the Osage River. Two years later, Bourgmont worked among the Kansas Indians.

In 1763, French authority in all of America came to an end. England, victorious in the long French and Indian War, received the Canadian provinces and all French rights to land east of the Mississippi River. New Orleans and Louisiana, West of the Mississippi River, had already been ceded by France to Spain in 1762.

Spain showed little interest in the Quivira country and thus regained it, yet the development of Kansas began under its ownership. Pierre Laclede Liguest, with Auguste and Pierre Chouteau of the French fur trading family, established headquarters at St. Louis in 1764 and sent agents from there to the Indians of Missouri, Arkansas, Nebraska, and Kansas. Although few, these agents cleared the paths by which Kansas emerged from a little-known region into a definite territory.

In 1801, the Treaty of Madrid, which confirmed the 1800 Treaty of San Ildefonso, retroceded Louisiana, west of the Mississippi River, to France. This move, which renewed France’s colonial ambitions, alarmed the recently formed United States. France, under Napoleon, was at the height of its power and too dominant a neighbor to be regarded as placid. Recognition of this and other considerations led President Thomas Jefferson to propose that the United States purchase West Florida and New Orleans. Napoleon’s counterproposal, which offered the entire state of Louisiana, was accepted. On April 30, 1803, Louisiana, including the Kansas region, became the property of the United States.

Explorations sponsored by the United States began immediately. In January 1803, before the Louisiana Purchase was consummated, President Thomas Jefferson called Congress’s attention to the land west of the Mississippi River, pointing out the possibilities of trade and suggesting an appropriation of $2,500 to explore the country and further commerce. The appropriation was made, and an exploring party was organized under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Lieutenant William Clark.

In March 1804, the Territory was divided into two parts. Land south of the thirty-third parallel was named the Territory of Orleans; north of the parallel, including Kansas, became the District of Louisiana, attached for legal purposes to the Territory of Indiana.

On June 26, 1804, Lewis and Clark landed at the mouth of the Kansas River on the first lap of their expedition. By July 4, they had reached a stream in the present Doniphan County, which they named “Independence Creek” in honor of the day, firing an evening gun and rationing out an additional gill of whiskey by way of celebration. Two years later, on August 5, 1806, they returned to the mouth of the Kansas River with the first reliable information on the climate, topography, and general features of the western country.

Before the conclusion of the first expedition, a second was organized by the military commandant of Louisiana, General James Wilkinson, and set out from St. Louis on June 24, 1806, under the command of Captain Zebulon M. Pike. He visited the Osage Indians in Missouri and the Pawnee on the Republican River, arriving among the latter on September 25. Here, he found a Spanish flag floating over their council tent. The purchase from Napoleon did not fix the western boundary; the United States claimed territory extending to the Rocky Mountains, whereas Spain fixed the boundary much farther east. Pike demanded that the Spanish flag be hauled down and the American standard raised in its place, thus ending all Spanish claims east of the Rockies. He turned south toward the Arkansas River and followed it to the present site of Pueblo, Colorado, where he discovered the mountain now known as Pike’s Peak. As this was encroaching on Spanish territory, he was captured and taken to Mexico. During his months of captivity, Pike gathered considerable information on the prospects for trade with the Mexican provinces. The accounts of his travels, published in 1810 on his return to the United States, generated considerable interest in these provinces.

He wrote enthusiastically about parts of Kansas but saw no possibilities for white settlement in the arid portions of the Louisiana district. “These vast plains of the western hemisphere,” his account reads, “may become in time as celebrated as the sandy deserts of Africa; for I saw in my route, in various places, tracts of many leagues where the wind had thrown up the sand in all the fanciful forms of the ocean s rolling wave, on which not a speck of vegetable matter existed.”

Maps, presumably based on Pike’s report and showing the desert reaching from the western line of the Missouri and Arkansas Rivers to the Rocky Mountains, from the Platte to the Red River, were incorporated into the school geographies of that period. This misconception gave rise to the legend of a “Great American Desert” that encompassed the entire state of Kansas.

Meanwhile, on March 3, 1805, the District of Louisiana was erected into the Territory of Louisiana, independent of the Territory of Indiana and with its own legislative powers.

Manuel Lisa.

Twelve years elapsed before another expedition was attempted, during which a series of events influenced Kansas’s future. In 1807, Manuel Lisa, a Spanish fur trader, established several trading stations at the headwaters of the Missouri River. The Missouri Fur Company was organized the following year by Lisa, along with Auguste and Pierre Chouteau, and a chain of trading posts was established throughout the western country. This company was dissolved in 1812 and was succeeded by the American Fur Company of the Chouteaus, which began to concentrate its activities in Kansas.

On June 4, 1812, the Territory of Missouri, with its western boundary approximating that of the present State of Missouri, was created from the Territory of Louisiana. The remainder was left without law or official identification for a quarter of a century.

The expedition of Major Stephen H. Long, a scientific exploration commissioned by the Government, ascended the Missouri River to Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1819. Long camped there for the winter, then moved south to the Platte and Red Rivers and entered Colorado, where members of his party made the first ascent of Pike’s Peak and returned to the Mississippi River via the Red River. Following Pike’s path, his expedition accumulated scientific data and introduced the first steamboat to Kansas waters. The Western Engineer entered the mouth of the Kansas River on August 10, 1819, and transported his party up the course for one mile. Here, the mud left by floodwaters necessitated a return and continued upstream along the Missouri River.

A period of even greater significance for the future of Kansas followed. In 1818, the Missouri Territory sought admission to the Union as a slave State; simultaneously, Alabama, also a slave state, sought admission. Alabama was admitted in 1819, helping to balance the power of the opposing factions between free and slave States. The debates over Missouri resulted in the Missouri Compromise, passed on February 17, 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slave State but stipulated that all future States West of the Mississippi and north of the 36°30 ′ line would be free. On August 10, 1821, Missouri was admitted to the Union under the terms of the compromise. The question of slavery shifted to the territory west of the Mississippi River, where it was to flare anew in Kansas. Two years later, the boundary between Missouri and Kansas was fixed.

Thomas Hart Benton, Senator from Missouri, began in Congress his championship of western development in 1824, only to meet with opposition such as the following from Daniel Webster: “What do we want with this vast and worthless area, of this region of savages and wild beasts, of deserts, of shifting sands and whirlwinds, of dust, of cactus and prairie dogs; to what use could we ever hope to put these great deserts, or those endless mountain ranges, impenetrable and covered to their very base with eternal snow? What can we ever hope to do with the western coast, a coast of 3,000 miles, rockbound, cheerless, uninviting, and not a harbor in it? Mr. President, I will never vote one cent from the public treasury to place the Pacific Coast one inch nearer Boston than it is now.”

The Reverend Isaac McCoy, a missionary to the Indians east of the Mississippi River, journeyed to Washington to propose removing his charges to western reservations beyond the influence of white settlements. His proposal was favorably received, and Kansas was, in the main, selected to provide the reservations, for it was still considered a desert country and of no value.

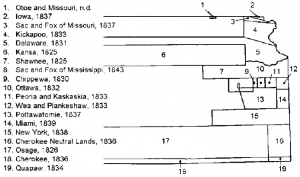

In 1825, the Government arranged treaties with the Osage and Kanza tribes, whereby they gave up their lands in eastern Kansas to make way for the emigrant tribes. The first allotment was granted to the Shawnee; then, in rapid succession, came the Delaware in 1829; the Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Kaskaskia, Peoria, Wea, and Piankashaw in 1832; the Sac and Fox and the Ioway in 1836; the Miami in 1840; and the Wyandot in 1843. All were crowded onto small reservations in the eastern part of the State.

With them came the missionaries, who had already taught them the rudiments of civilization. Two Presbyterian missions were established in 1820 for the Osage: the Union on the Neosho River and the Harmony on the Marais des Cygnes River. In the spring of 1827, Daniel Morgan Boone, son of Daniel Boone, was sent by the Government to teach farming to the Kansas Indians occupying the southern part of Jefferson County. He established his family, the first white family in the Territory. His son, Napoleon, born August 22, 1828, was the first white child born within the State. In 1829, the Reverend Thomas Johnson introduced Methodism to the Shawnee, establishing a mission near the present town of Turner in Wyandotte County. Four years later, the Reverend Jotham Meeker brought the first printing press to the Shawnee Baptist Mission, and on February 24, 1835, he published the first issue of the Shawnee Sun, the first newspaper in Kansas.

By 1830, trading posts were scattered throughout eastern and central Kansas, reaching from the Platte to the Red River. Within a few years, ferries were strung across the Missouri and Kansas Rivers, roads were cut along the ridges, patches of farmland were cleared and planted, and cabins were built along the highways. All this was the work of the Indians, under the direction of missionaries and Government agents.

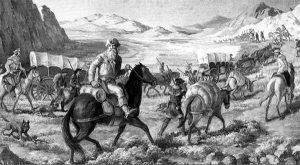

Captain William Becknell had made the first successful trade journey to Santa Fe in 1821, establishing the route of the Santa Fe Trail. Twelve months later, he led the first wagon train along the trail, beginning the valuable commerce of frontier days. As a midway course between Benton’s proposals for western development and the opposing view, Congress authorized the survey and marking of the Santa Fe Trail in 1825. Fort Leavenworth was established as “Cantonment Leavenworth” in May 1827. Westport (now Kansas City, Missouri) became a depot on the Santa Fe Trail in 1833. Ten years later, the city of Wyandot (Kansas City, Kansas) was founded by the Wyandot Indians.

At this time, the Government sent out another exploration under Lieutenant John C. Fremont. He entered Kansas in 1842, completing his outfit at Cyprian Chouteau’s trading post in Wyandotte County on June 10. With Kit Carson as his guide, Fremont explored the Kansas and Platte Rivers and surveyed the South Pass of the Oregon Trail, thereby winning him the title of “Pathfinder.” He followed this exploration with three more, in 1843, 1845, and 1848. Accounts of these expeditions were published immediately by the Government to direct attention to the West, and they were highly successful.

The Mexican-American War ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, ratified on May 30, 1848. By its terms, the Rio Grande became the boundary between Texas and Mexico. From El Paso to the Pacific, the westward international boundary was almost as it is now. Northward, the ceded territory extended from a league below San Diego, California, to the Oregon Country at 42 ° north latitude; eastward, it reached the Rocky Mountains. This vast region embraced what was then known as New Mexico and Upper California. What now corresponds to a strip of Texas, the greater parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona, all of California, Nevada, and Utah, and a little of Wyoming. In addition, the 1846 Treaty with Great Britain established the United States’ right to the Oregon Country. Thus, in two years, the United States cleared from its continental path to the Pacific all conflicting sovereignties as far north as the forty-ninth parallel.

This resulted in a tremendous increase in migration over the Kansas trails.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated January 2025.

Also See:

Early Expeditions Through Kansas

Source – Federal Writers Project, 1939.